Segmenting the Labyrinth:

Sketch Studies and the Scala

Enigmatica in the Finale of Luigi Nono’s Quando stanno morendo Diario

Polacco N. 2 (1982)

Friedemann

Sallis

I can’t utter too many warnings

against overrating these

analyses, since after all they

only lead to what I have

always been dead against: seeing how it is done;

whereas I have always helped people to see: what it is!

Arnold

Schoenberg

Patricia Hall once observed that musical sketches are most helpful for

“highly defined theoretical systems.” She then went on to state that sketch

material pertaining to music created within transitional (i.e. poorly defined)

systems is likely to be ambiguous, telling us little more than what we may

already have discovered in the finished score.

With respect, I submit that the very idea of stable, “highly defined

theoretical systems” somehow standing outside of the historical flux of musical

thought is at once a figment of my colleague’s imagination and one of enduring

myths of modern music theory. Be that as it may, Gianmario Borio has since

turned Hall’s observation on its head. Referring to the study of new music

composed during the latter half of the twentieth century, he wrote that

philological research (i.e. sketch studies) should not be used to confirm

analytical hypotheses formulated in advance, but rather it becomes the conditio

sine qua non for the formulation of these hypotheses.

In other words, when studying music for which appropriate analytical hypotheses

have not yet been developed or remain underdeveloped, the careful examination

of the composer’s surviving sketch material often provides the requisite

criteria with which a plausible analytical hypothesis can be established.

To exemplify this point, the last 36 bars of the third and final

movement (labelled Part III)

of Luigi Nono’s Quando stanno morendo, Diario Polacco N. 2 for

two sopranos, mezzo soprano, contralto, bass flute, violoncello and live

electronics will be examined in some detail. The goal is to show how a study of

the composer’s working documents can provide a framework, within which basic

units of Nono’s compositional technique can be identified. By combining data

obtained from a close reading of the published score and surviving sketch

material with the information gained from what we know of the work’s context,

the student of this music can more efficiently circumscribe what Allen Forte

once called the “analytical object.”

To accomplish this task we will scrutinize working documents Nono used to

produce Quando stanno morendo, as well as the related work ¿Donde

estas, hermano? Per ‘los Desaparecidos en Argentina’ for two

sopranos, mezzo soprano and contralto (1982), and we will also examine aspects

of the context within which these two works were written.

The Archivio Luigi Nono conserves a substantial collection of diverse

documents pertaining to the composition of Quando stanno morendo. At

present that collection contains 827 leaves of manuscript material. Of these,

420 leaves have been classified as sketches and drafts in the narrow sense of

the term (i.e. documents containing work directly related to the compositional

process). The rest of the collection is made up of a fair copy (47 leaves) and

360 leaves of various documents pertaining to pre-compositional stages and

documents related to the first performance of the work. The size of the collection is typical of

compositions written in the early 1980s and is representative of Nono’s

compositional practice.

The four-voice a cappella Finale of Quando stanno morendo

constitutes not only the chorale-like concluding section of Part III, but also

functions as a coda for the entire work. This is not the first time Nono has

turned to the unadorned human voice to complete a composition. His Epitaffio

No. 3 Memento, Romance de la Guardia civil española (1952-53) for

choir and orchestra ends in a similar manner. This early work sets a poem by

Federico García Lorca in which the author presents a stunning confrontation

between order and chaos, law and magic, power and

lyricism, and authority and liberty.

The work ends with unaccompanied choir singing the last four lines of García

Lorca’s allusive text (bars 411- 442).

The last 31 bars are the only section in which the vocal ensemble is presented

a cappella and in which it actually sings (in the preceding sections the

ensemble functions as a speaking choir), setting it off from the rest of the

composition. The text is clearly meant to be understood as a concluding

statement.

Similar concluding sections for unaccompanied voices or voice can also be found

in works such as Intolleranza (1960-61) and La fabbrica illuminata

(1964).

Jeannie Guerrero has examined this aspect of Nono’s work and noted that

the concluding function of these finales is not only a matter of content but

also of form. She contrasts the multidimensional counterpoint and complex

textures of Sarà dolce tacere (1960) with the retrograde canon at the

end in which these dense structural procedures are clarified.

The multidimensional counterpoint thus reaches utter silence at the

conclusion of Sarà dolce tacere. The ending serves as a structural cadence for

the entire song and aptly reflects the work’s title, “It will be sweet

silence.” Further the gradually aligning generator paths throughout the middle

of the song indicate a large-scale progression toward the final cadence. The

increasing contrapuntal alignment across four dimensions binds the entire work

into an organic whole.

Compared to the ‘noisy’, agitated textures of the beginning and middle

of Sarà dolce tacere, the retrograde canon at the end of the composition

“performs the act of falling silent.”

In Cori di Didone (1958), Guerrero notes that the duration-dynamics

palindrome of the Finale brings the complex, chaotic textures of the work to

rest. At the same time, this place of structural repose resonates strongly with

the text’s emphasis on the “silence of dead seas.”

In the following, we shall see that the homophonic textures of the a cappella

Finale of Quando stanno morendo bring into focus certain structural

aspects of the music of preceding sections, while at the same time presenting a

concluding commentary on the work as a whole. For reasons that will become

apparent in the course of the text, this article will focus on Parts II and III

of Quando stanno morendo. In any case, an exhaustive analysis of the

entire work would not be possible within the space provided here.

Work and Context

Completed on 3 September 1982, Quando stanno morendo is the third

of a series of four works conceived and written at the Experimental Studio of

the Heinrich Strobel Foundation of the Südwestfunk at Freiburg im Breisgau

between 1981 and 1983.

It is one of the first in which Nono successfully integrated the real-time

manipulation of sound using information technology developed specifically for

this purpose at the Foundation. The innovative concepts, procedures and

technologies developed at the Foundation would strongly mark Nono’s

compositions written during his last decade from both a technical and an

aesthetic point of view and constitutes one of the primary factors providing

coherence to what has come to be known as the composer’s late work (1980-90).

This being said, the music produced during this period is not merely about

applying new technology to old compositional problems. Quando stanno morendo,

first performed in Venice on 3 October 1982, has a rich history that is

recounted in the composer’s dedication.

In October 1981 the organizers of the Warsaw Music Festival invited me

to compose

Diario polacco No.2 which should have taken place this year.

Then came the 13th of December.I have had no news of the

friends who invited me.

The organizers were dismissed, the Festival did not take place.

My desire to write this Diary became even stronger.

I dedicate it to my Polish friends and companions, who - in exile, in

hiding, in prison, at

work - resist and hope even if they despair, believe even if they are

incredulous.

The suppression of Solidarno by General Jaruzelski with the tacit support of the Soviet Union in

December 1981 had a devastating impact on Nono. This can be clearly felt in the

work’s libretto: a collage of fragments taken from poems by Czes_aw Mi_osz, Endre Ady, Aleksandr Blok, Velemir Khlebnikov and Boris Pasternak,

selected and edited by Massimo Cacciari, who became one of Nono’s principal

advisers during the last decade of his career. Part II (the second movement) is

entirely based on a text by the Russian futurist poet, Velemir Khlebnikov

(1885-1922).

In their ‘Notes’ concerning the elocution of this text, the editors of the

published score state: “The text requires enunciation that is free, not

measured, serious and decisively articulated: an apostrophe sculpted to produce

dramatic introspection rather than declamation.”

The text is thus not only to be heard for its musical value but also for its

semantic content. Its central section, translated in Italian, reads:

Mosca chi sei? Moscow

– who are you?

Io so che voi siete I

know that you are

lupi ortodossi. orthodox

wolves.

Ma come mai, come mai non udite But

how, how on earth don’t you hear

Il fruscìo dell’ago della sorte? the

rustling of the needle of fate?

Figure 1: Transcription and English

translation of lines 7 to 11 of the text of Part II

Khlebnikov’s words resonate well with the context in which they were

written, i.e. the disintegrating regime of Tsar Nicolas II. That Nono and

Cacciari should have chosen to use the work of this particular poet to make a

statement on the repression of Solidarno__ speaks volumes on their attitude toward the Soviet regime under Leonid

Brejnev.

Compositional History of the Finale

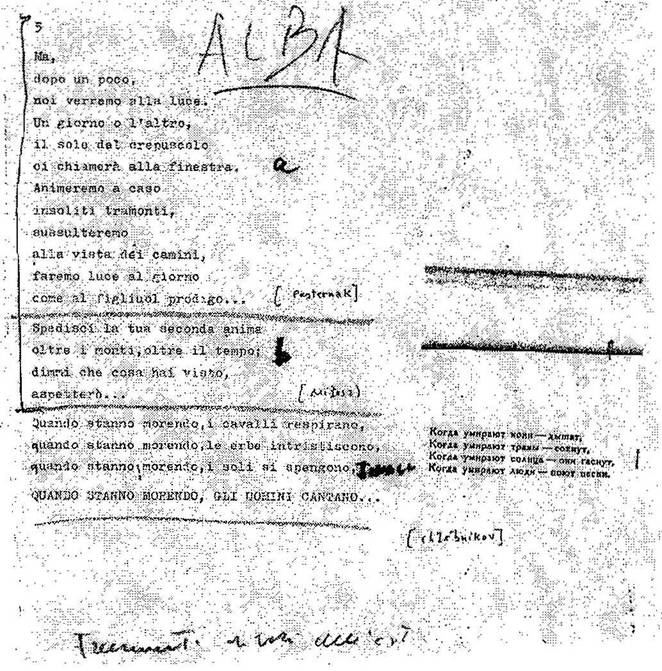

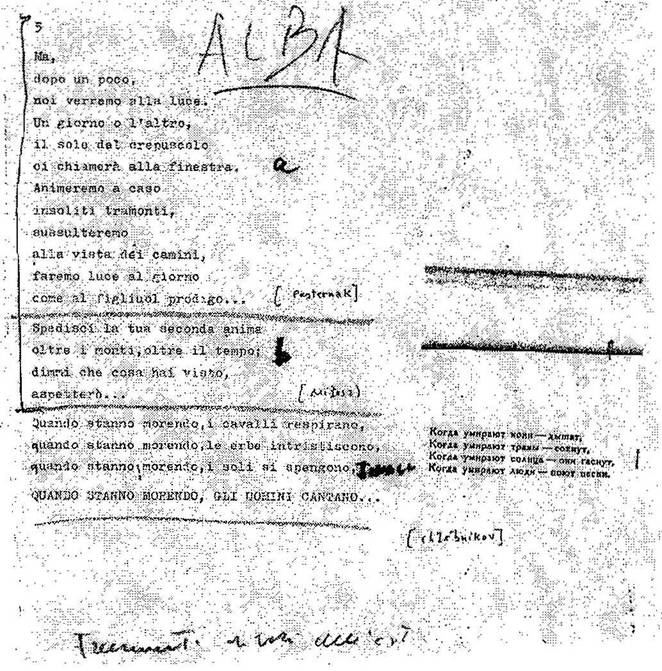

The compositional history of the Finale (Part III, bars 59-94) is complex

and in some respects remains unclear to this day. In the following Plate we see

an early typescript of the text fragments which established the ternary

framework of Part III.

The word “ALBA” scrawled graffiti-like near the top of the page means

“dawn” and can also refer to the age-old vocal genre otherwise known as ‘aube’

or ‘aubade’. Carola Nielinger-Vakil has pointed out that the term

appears on numerous sketches from the late 1950s onwards and almost invariably

refers to the poetry of Cesare Pavese, in which the unspoilt beginning of the

day - dawn - stands for hope.

The

lines of Pasternak’s text that begin Part III refer to a period when we will

return to light (“noi verremo alla luce”). Commenting on Quando stanno

morendo shortly after the work had been composed, Nono wrote:

And if each thing were to be seen in this way - as unheard, individual,

indivisible - then each thing

would escape the fate of death to which it would be consigned by the

winter of the “orthodox wolves”.

If we are able to sustain this expectation, then we might be able to

shine the “light of day” and thus

defeat the death that today hangs over us.

The musical tone of Part III is also far less agitated and more lyrical

than that of Part II, conforming to the general idea of a ‘chant d’aube’.

Marco Mazzolini has identified cuts which were made in both the text and

the music of Part III (see Figure 2 below).

Mazzolini’s observations are based on two scores of the work, which he labelled

“Stesura originaria” [Original draft] and “Stesura con taglio”[Draft with cuts]

(see Example 2 below). Initially Nono had intended to divide the first text fragment(marked ‘a’ in Plate 1) into three

subsections. In the end he cut the last part of Pasternak’s text following the

word ‘chiamerà’ and in so doing eliminated the last 18 bars of what would have

been the third subsection of a fifty-four-bar ternary form. He also cut the

first three lines of the third text fragment, leaving only the last line of

Khlebnikov’s text and in so doing eliminated half of the music that had been

composed for this final section of the work.

Plate 1: Luigi Nono, Typescript of the

Original Text of the Third Movement.

Reproduced with the kind permission of the Archivio Luigi Nono. © Eredi

Luigi Nono.

“Stesura originaria” [Original Draft] “Stesura con taglio”

[Draft with cuts]

(Original structure of Part III) (Definitive

structure of Part III)

a) 1. bars 1-21 a) bars

1-36 (subsection 3 was cut. In the published

2. bars 22-36 score,

double bar separates bars 21 and 22,

3. bars 37-54 identifying

the dividing line between subsections1 and 2.)

b) bars 1-22 b) bars

37-58

c) bars 1-70 c) bars

59-94 (bars 1-34 of the earlier version were cut)

Figure 2: Comparison of the original and

definitive structures of Part III presented by Marco Mazzolini in 1993

.

These cuts were made late in the compositional process. The Archivio

Luigi Nono conserves an autograph fair copy (catalogue no. 47.12.02, no doubt

the document Mazzolini labelled the “stesura originaria” in his 1993

conference). This fair copy is dated 3 September 1982. The publication of this

date at the double bar in the published score (which presents the “stesura con

taglio”, or definitive version of Part III) is misleading because the cuts must

have been made after 3 September 1982. Erika Schaller observes that during the

last phase of his career, Nono would often

make cuts during rehearsals leading

up to the first performance.

As can be seen in Plate 1 above, the Finale of Part III was originally

supposed to have set four lines of another text fragment by Khlebnikov.

Quando stanno morendo, le erbe

intristiscono When they are dying,

[blades of] grass wither

Quando stanno morendo, i cavalli respirano When they are dying, horses breathe

Quando stanno morendo, i soli si spengono When they are dying, suns fade away

Quando stanno morendo, gli uomini cantano When they are dying, men sing

Figure 3: Transcription and English

translation of the last four lines of text presented in Plate 1

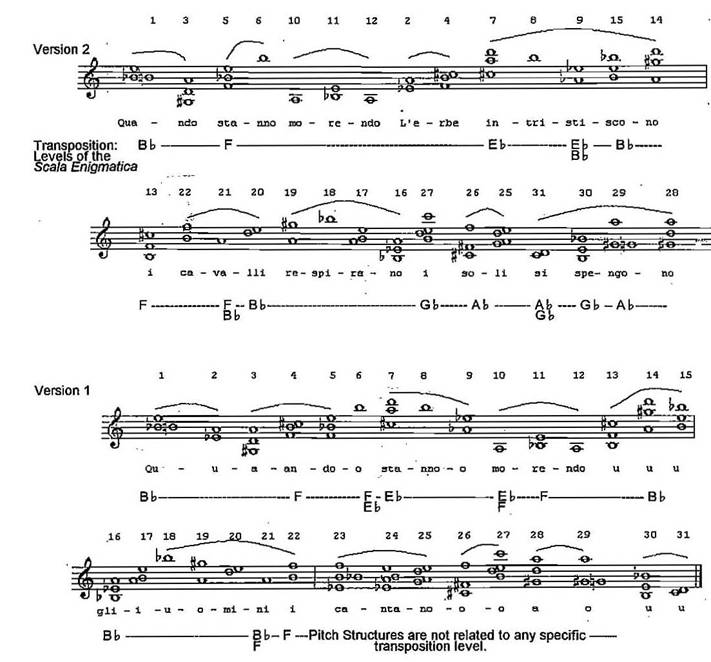

The music composed to set this text, exists in three distinct versions,

which for the purposes of this paper will be labelled 1, 2 and 3. The numbers

refer to the chronological order in which Nono composed the three versions.

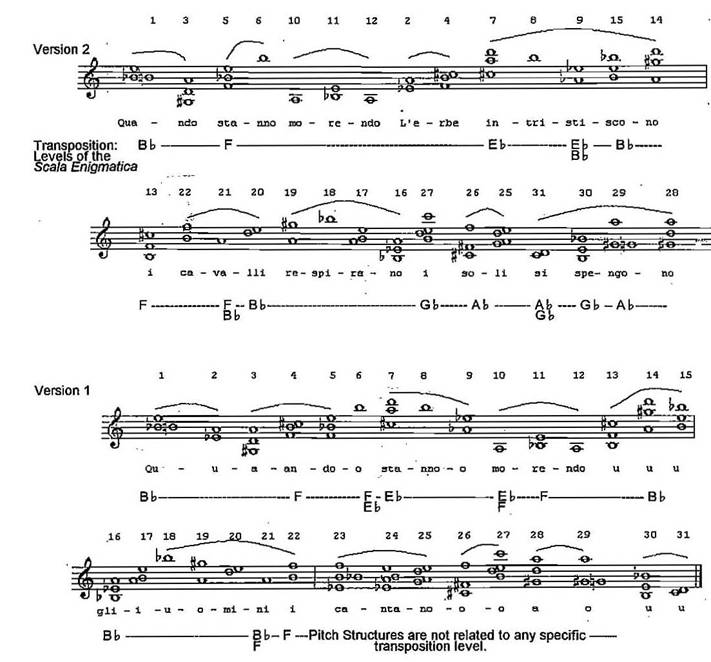

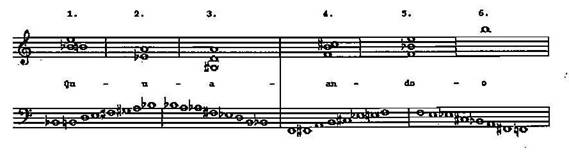

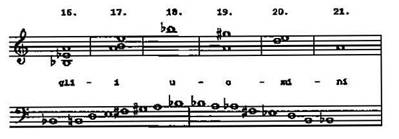

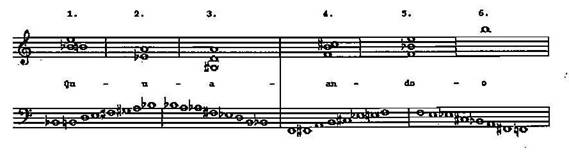

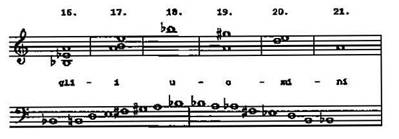

Example 1: Quando stanno

morendo, Part III, Original Draft of the Finale, bars 1-70, Pitch Content

of Versions 2 and 1 of the Finale

1 Version 1 is the last thirty-six bars as they appear in the published

score, which set only the last line of Khlebnikov’s text (see Example 1).

2 Following the completion

of version 1, a new version of the same music was composed by permuting the

order of the compositional units. Version 2 was to have set the first three

lines of Khlebnikov’s text, and, together the two versions would have

constituted a Finale seventy bars in length, twice as long as it actually is.

As noted above, Nono cut version 2. In the following example the dyads,

trichords and tetrachords of versions 2 and 1 are presented as they appear in

the “stesura originaria” (duration values have been eliminated). The intervals

and chords of version 1 are numbered and a cursory comparison of the two

versions reveals that except for chords 23 and 24, which are missing in version

2, the pitch content of version 2 is identical to that of version 1.

3 On 28 September 1982, three and a half weeks after having completed Quando

stanno morendo, Nono used version 1 to create a new work entitled ¿Donde

estas, hermano? Per ‘los Desaparecidos en Argentina’ for two sopranos, mezzo

soprano and contralto. He did this by replacing Khlebnikov’s text with the

Spanish words “¿Donde estas hermano?” With regard to the music, though minor

changes do occur in dynamics, phrasing and note doublings, the pitch and

duration structures of versions 1 and 3 are identical.¿Donde estas hermano?

was first performed on 24 November 1982

in Cologne as

part of a

solidarity concert organized by the German section of the ‘Association

Internationale de Défense des Artistes victimes de la répression dans le monde’

(AIDA). The concert’s goal, clearly

reflected in Nono’s subtitle, was to reinforce public awareness of those who

had disappeared during the years of state sponsored terror and specifically of

the approximately one hundred Argentinean artists who remained unaccounted for

at that time.

The event’s motto was ¿Donde estas, hermano?, which Nono appropriated

for both the title and the text of this new vocal work. ¿Donde estas

hermano? has since been published and recorded. This last version is

mentioned here in passing for two reasons: first, it clearly demonstrates that

though the texts of Nono’s works are always important and should never be

ignored, they do not necessarily constitute the determining factor for the

organization of the music; second, this

version shows that the Finale of Quando stanno morendo can be understood

as a musical entity in its own right and can thus be analyzed as a

self-standing piece, without taking into account the live electronics that are

minimally present in version 1 (see footnote 10 above).

How do we know that version 2 was derived from version 1 and not the

other way around? The study of sketch material pertaining to Quando stanno

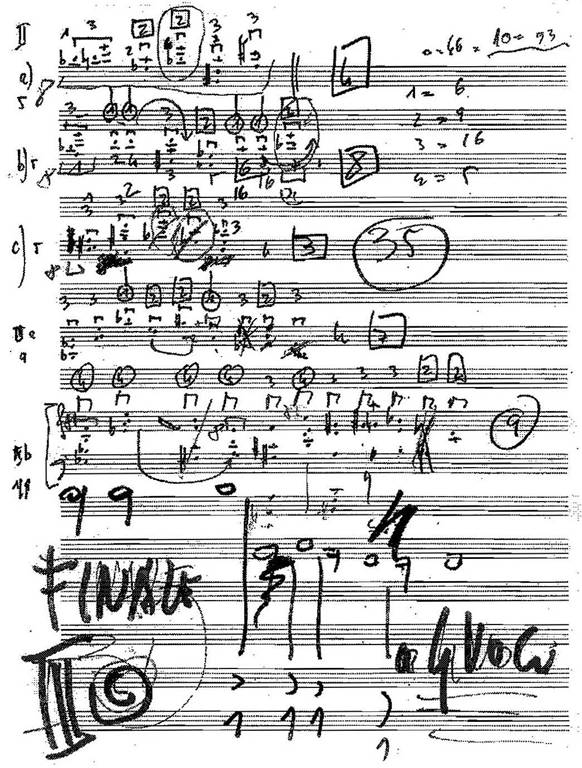

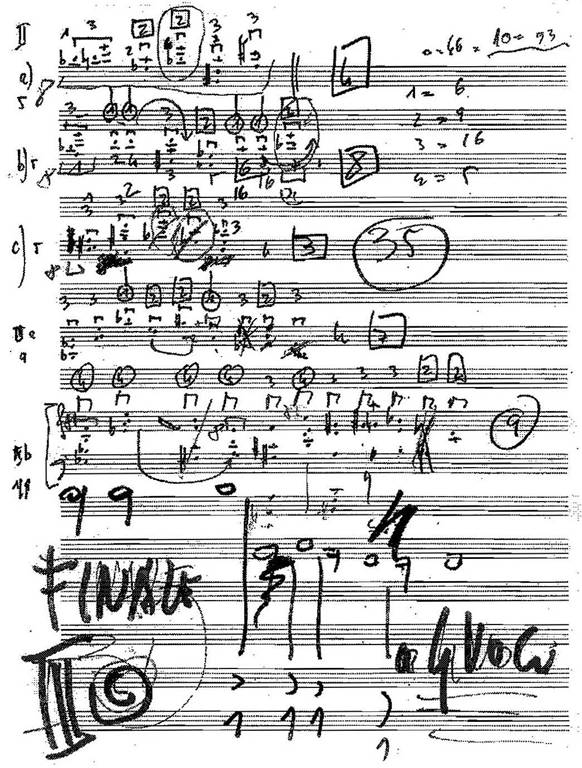

morendo provides an answer. Plate 2 below presents a sketch used by Nono as

he began to compose the Finale. It shows how vocal parts of the previously

composed Part II and the first two sections of Part III were used to create the

pitch structures of version 1.

The Roman numerals in the left margin refer to Parts II and III and the

lower case letters refer to the sections of each movement. The pitch content of

this page is almost completely derived from the vocal parts in the five

sections of Parts II and III that precede the Finale. For example, the pitches

notated on the uppermost staves of the page present the melodic material sung

by the second soprano and mezzo-soprano in sections ‘a’ (bars 10-37)

‘b’ (bars 56-81) and ‘c’ (bars 82-105) of Part II. Except for one note the

correspondence between the sketch and the vocal lines in Part II is exact both

in terms of pitch and register.

The pitches notated on the following staves present the melodic material of

Part III sung by the first soprano in section ‘a’ (bars 1-27) and by the

contralto in section ‘b’ (bars 37-53).

Plate 2: Quando stanno morendo,

Part III, bars 59-94, Sketch.

Reproduced with the kind permission of the Archivio Luigi Nono. © Eredi

Luigi Nono.

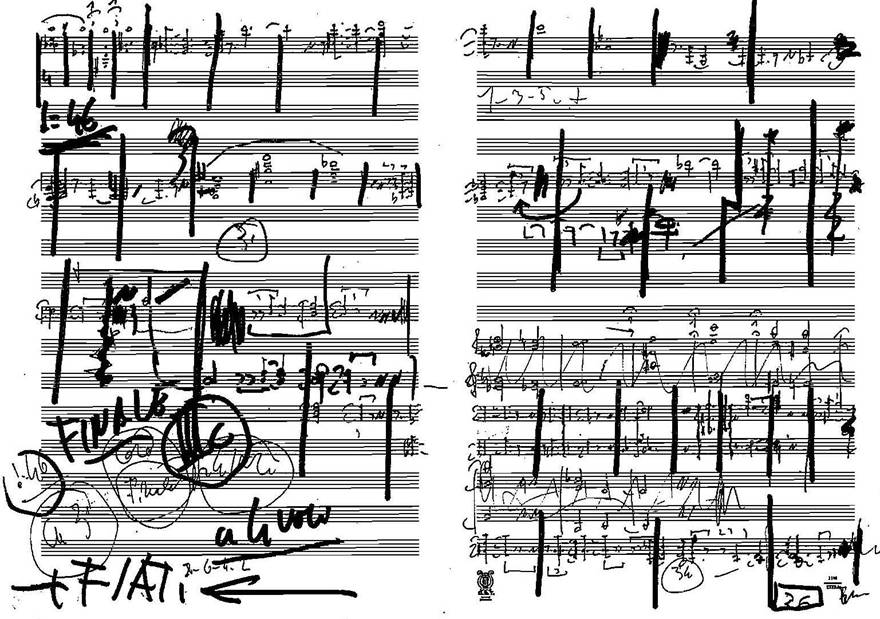

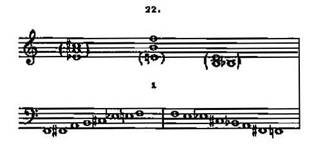

Plate 3: Quando stanno morendo,

Part III, bars 59-94, sketch.

Reproduced

with the kind permission of the Archivio Luigi Nono. © Eredi Luigi Nono

This sketch presents the compositional units with which Nono composed

the four-voice chorale of the Finale. The

units are made up of single pitches, dyads, trichords and tetrachords. The

column of numbers written in the upper right corner (1=6; 2=9; 3=16; 4=5)

indicates the sum of one-, two-, three-, and four-note units Nono intended to

use at one point in the compositional process. The octava

bassa signs in

the left margin show

Nono modifying register. The pitch content of the entire upper staff is

sung an octave lower in the Finale than where the same material was sung in the

second movement. Nono also eliminated units (the encircled tritone e''' b''flat

on the first staff, the same interval on the third staff, as well as the

following tritone) and changed their order (the b'' became the fourth unit on

the second staff). At some point he appears to have envisioned the Finale being

made up of 35 units (see the encircled figure on the right side of the page).

In the published score, the Finale contains 31 units: the sum of the squared

and circled figures to the right of the compositional units.

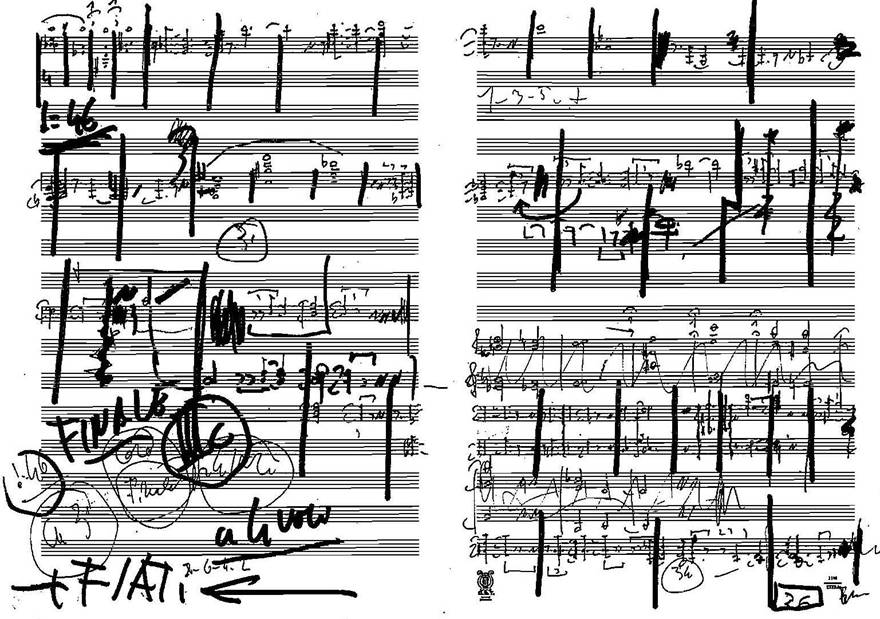

Some time after he had completed the page presented in Plate 2, Nono set

his compositional pitch units in a metric structure and added duration to the

pitch structure of the Finale. This can be seen on the bifolium presented in

Plate 3. In both sketches presented in Plates 2 and 3, Nono used different

coloured ink (blue, red and black) to distinguish between first ideas and

corrections. Despite the sketch-like quality of the writing in Plate 3, the

pitch and durational aspects of the Finale are now firmly in place. Though the

text, phrasing, dynamics and the live electronic manipulation are still

missing, the document presented above can be seen as a first rough draft of

what would become the music of the Finale of Quando stanno morendo and

of ¿Donde estas hermano?

From the information gleaned from these two pages, we are able to draw

the following conclusion. The sketches in Plates 2 and 3 present the

compositional units in the order that corresponds with version 1 of the Finale.

This confirms that version 2 is derived from version 1 and not the other way

around, because the structures of version 1 are directly related to previously

composed vocal material of Parts II and III.

Segmenting Pitch Structure in the Finale

What are we

to make of this seemingly chaotic collection of mainly 3-5 and 3-8 trichords in

the Finale of Quando stanno morendo? How are these compositional units

related to one another and how did Nono recompose this material for version 2?

In a broader context, how should we understand these harmonic structures which

are so characteristic of Nono’s late work as a whole? The phrase structure of

vocal music (following text/music relationships) often constitutes a good point

of departure for an examination of the above questions. However, as we have

seen, the same compositional units were used to set three completely different

texts, and, in the case of ¿Donde estas hermano? (version 3 of the

Finale), a new text was simply superposed on a pre-existing musical structure

(version 1). As a result, though the text/music relationship is significant, it

can not be the sole reference for a coherent explanation of Nono’s phrase

structures.

One promising line of endeavour in this particular case is to examine

how the so-called scala enigmatica is related to the pitch structure in

the Finale of Quando stanno morendo. Commentators and analysts have

noticed the presence of this scale in Nono’s late work, beginning with the

string quartet Fragmente - Stille, An Diotima (1980).

According to Laurent Feneyrou, it is so pervasive in the compositions of the

1980s that it parallels Nono’s use of the all interval row in works of the late

1950s.

The scala enigmatica was invented

by Adolfo Crescentini, a Bolognese music professor who, in a letter published

in the Gazetta Musicale di Milano on 3 August 1888, challenged readers

to harmonize a seven-note scale made up of an eight-note pitch collection

organized in a succession of major, minor and augmented seconds, the eighth

pitch being the lowered fourth degree in the descending version (see Example

2). The following year, Giuseppe Verdi used the scale as a cantus firmus in his

"Ave Maria" (subtitled Scala enigmatica armonizzata a 4 voci

miste), which became the first of the Quattro Pezzi Sacri (1898).

Example 2: The Scala

Enigmatica as used by Giuseppe Verdi in “Ave Maria,” bars 1-16

In Nono’s compositions, the scala enigmatica never appears as such.

This fact has led some, notably Heinz-Klaus Metzger, Luigi Pestalozza and Jürg

Stenzl, to suggest that Nono used it as a kind of generalized background matrix

with only vague relationships to the structure of a particular work.

Paraphrasing Nono, Metzger stated that the scale should be seen as a

“generative constellation” [generativer Konstellation] from which the composer

derived his diastematic material, and went on to suggest that the beginning of

the string quartet Fragmente - Stille can be related to the scala

enigmatica transposed to A. He did not explain how he came to this

conclusion and indeed dismissed such explanations as pedantic.

More recent studies of Nono’s late work have attempted to provide a more

precise definition of the term “generative constellation.” Taking Metzger’s

remarks as his point of departure, Hermann Spree noted that in Fragmente-Stille,

An Diotima the scala enigmatica has neither a determinant

function (like that of a series) nor can it be dismissed as mere neutral background

material.

He observed that the pitches A, E-flat, D and A-flat are clearly present at the

very beginning of the string quartet and that this pair of interlocking

tritones presents the four transposition levels of the scala enigmatica

that play a framing role throughout the work. He also stated that the pitch

structure of the string quartet should not be understood as a succession of

transpositions, moving from one level to another, but rather as intervals and

chords derived from specific transposition levels which appear to be freely

mixed, leaving the impression that the music seems to hover between two or more

forms of the scale.

Contradicting Spree’s findings somewhat, the first fifteen units of

version 1 of the Finale of Quando stanno morendo can be grouped into a

succession of segments derived from specific transposition levels of the scala

enigmatica. The first three compositional units contain seven of the eight

pitches of the scale transposed to B flat. As is often the case in Nono’s late

work, tritones, perfect fourths and fifths, major sevenths and minor seconds

dominate the diastematic structures of the compositional units 1 through 3 and

continue to do so throughout the Finale.

The first trichord presents two characteristic intervals of the scale

transposed to B flat: with the minor second between the first and second scale

degrees and the tritone between the first and fourth scale degrees.

The minor second is spelled enharmonically as B natural rather than as C

flat.

Numerous analysts have noted the idiosyncratic manner with which Nono notated

music derived from the scale. Spree spoke of Nono’s “insensitivity” to

questions concerning enharmonic spelling.

Though this aspect of Nono’s writing does not provide an unequivocal key to the

composer’s pitch structures, notation can be an indication of how closely

various transposition levels of the scale are related to specific sections of

his music. For example, in an undated sketch produced for Prometeo, some

time between 1981 and 1985 (the period during which he composed Quando

stanno morendo), Nono copied out all twelve transpositions of the scala

enigmatica, starting on C at the top of the page and descending by

half-step to B at the bottom of the page (as though he were deploying a serial

table).

Nono’s notation of the scale in this table is not rigorously systematic (it

contains numerous inconsistencies), but neither is it incoherent. The guiding

principle seems to be the facilitation of reading and writing. Throughout the

sketch he avoids all infrequent accidentals: B sharp, F flat, all double sharps

and flats, etc. Though on occasion, the spelling of a degree in the ascending

form of the scale will differ from that of the descending form, this does not

occur frequently. In Example 3 below, the first six compositional units

(setting the word “Quando”) are placed above the transposition levels from

which they can be derived. The scales are spelled exactly as Nono wrote them in

his sketch for Prometeo.

Example 3: Quando stanno

morendo, Part III, Finale, Compositional Units 1-6 Placed Over

Transpositions of the Scala Enigmatica, Transcribed from a Sketch for

Prometeo

The spelling of all pitches conforms to that used in the sketch for

Prometeo. For example in compositional unit 1, the B natural conforms to

the manner in which Nono notated the second degree of the scale in both

ascending and descending forms. In cases where a discrepancy arises between the

spellings of the same degree on ascending and descending forms of the scale (G

sharp ascending and A flat descending in the B flat transposition for example),

Nono tends to choose spellings used in the ascending form. Of the first 22

enigmatica, only one pitch (A flat of unit 9, see Example 4 below) does not

conform to Nono’s idiosyncratic notation of the scale found in his sketch for Prometeo.

Example 4: Quando stanno morendo, Part III, Finale,

Compositional Units 7-15 Placed Over

Transposition of the Scala

Enigmatica, Transcribed from a Sketch for Prometeo.

The next

compositional unit (4) breaks with the previous group of three because it

contains F and C sharp, neither of which are found in the B flat transposition

of the scale. These two pitches are contained in the scale transposed to F. In

fact they are the only two notes of the scale on F which do not occur in the

scale on B flat. Furthermore, D and G sharp, the only two notes of the B-flat

transposition that do not occur in the F transposition, form the tritone of the preceding compositional unit (3). Thus units 3 and 4

display the strongest possible contrast that can be obtained between these two

overlapping pitch collections. Units 4 through 6 are made up of five of the

eight pitch classes of the scale transposed to F.

These five scale degrees are also characteristic of the scale on F: the lowest

note, the fourth in both ascending and descending forms, the augmented fifth

and the major seventh. Note should also be taken of the fact that unit 4 also

contains the tritone made up of the first degree and the ascending fourth

degree of the scale, analogous to the tritone found in unit 1. The

transposition levels from which these compositional units can be derived,

divide the setting of the word in two equal halves.

The transposition identity of compositional units 7 through 9, which set

the second word of the text (“stanno”), is not quite as certain as the first

two groups (see Example 4 below). The six pitches of these units all belong to

the scale transposed to E flat and all are in normal spelling.

Only one pitch (G) distinguishes the pitch collection of the E-flat

transposition from those of the B -flat or F transpositions and it is absent.

Consequently all of the pitches used in compositional units 7-9 could be

derived from the B-flat and F transpositions. This reading of the pitch content

of units 7 through 9 is however unsatisfactory because unit 7 contains a C

sharp and a D. The former is present in the B-flat transposition and the latter

in the F transposition, making the trichord impossible to classify. Moreover,

the six pitches of units 7 through 9, like those of units 4 through 6,

correspond to characteristic scale degrees of the E-flat transposition: the

lowest note, the fourth degree in both ascending and descending forms, the

augmented fifth, the augmented sixth and the major seventh.

The units 10 through 12, which set the word “morendo”, can be derived

either from the B-flat or the F transpositions of the scale. Their spelling conforms

to both transpositions. However, when combined with compositional unit 13,

which contains pitches that can only be derived from the scale on F, the set

(units 10 -13) constitutes a convincing whole. Here again, the pitch material

of these units is made of six characteristic pitches of the scale on F: the

lowest note, the major third, the fourth degree in both ascending and

descending forms, the augmented fifth, and the major seventh.

The last three units of this first section of the Finale are in a mirror

relationship with units at the beginning, which corresponds to the fact that

the vocal line of the third section of Part II is the retrograde of the vocal

line of the first section (see the sketch presented in Plate 2: the pitch

material of the third staff marked “c” is in a retrograde relationship with the

pitch material of the first staff marked ‘a’). However,

this relationship is not exact: units 1 - 3 - 4 correspond to units 15 -14 -

13. Unit 2, which should have been placed between units 15 and 14, is missing.

As noted above, when Nono constituted the compositional units of the Finale, he

deliberately eliminated the interval e''-flat – a'', which would have been

placed between units 14 and 15 (see Plate 2, third staff from the top of the

page). If we examine the register displacement of pitches making up these

units, it is clear that Nono was constructing a tight symmetric relationship

between the compositional units at opposite ends of this first section of the

Finale. In all three pairs of trichords, at least one note retains its initial

register. The tritone of units 1 and 15 is inverted (the augmented fourth

equals the diminished fifth); the tritone of units 3 and 14 is transposed two

octaves higher, and the tritone of units 4 and 13 is inverted in the opposite

direction to that of units 1 and 15. Clearly, these complementary melodic

patterns (the first curving down, the second curving up) were consciously

composed, reinforcing the notion that the units of the B-flat sections at

opposite ends of the first fifteen compositional units belong together and do

have a shared identity (see Example 5).

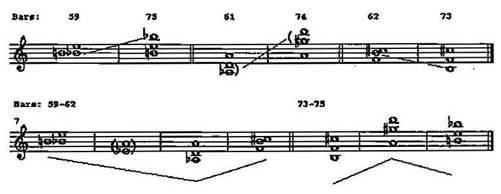

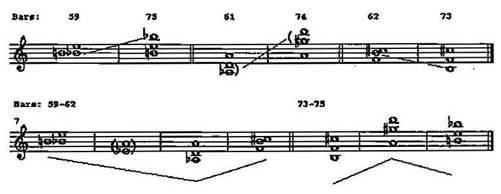

Example 5: Quando stanno morendo, Part III, Finale, Compositional Units 1-4 (bars 59 - 62) and 13 –

15 (bars 73 - 75)

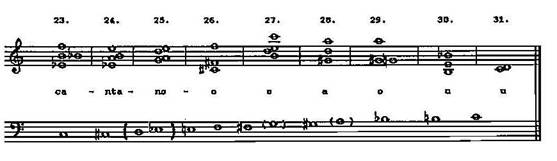

Units 16 through 21 can be derived from the scala enigmatica on B

flat (see Example 6). Though the group contains twice as many compositional

units, its pitch material is exactly the same as that deployed in units 1

through 3. In both cases, seven of the eight pitch classes of the B-flat

transposition are deployed and in both cases the missing pitch is F sharp.

Example 6: Quando stanno morendo, Part III, Finale, Compositional Units 16-21 Placed Over the B-flat

Transposition of the Scala

Enigmatica, Transcribed from a Sketch for Prometeo.

Unit 22 contains an F and thus breaks with the preceding group derived

from the B-flat transposition (see Example 7 below). This suggests the

beginning of a new group of units derived from the F transposition, notably

because it contains the characteristic tritone formed by the lowest tone and

the ascending fourth degree of that scale. Unit 22 could be grouped with units

23 and 24, because the pitches of the latter two units can also be derived from

the F transposition of the scale. This interpretation is however problematic.

As shall be shown below, units 23 and 24 appear to belong to the last section

of the Finale. However, this segmentation leaves unit 22 in an orphaned

situation, a lone dyad derived from the F transposition, isolated between two

larger groups; the only such occurrence in the Finale. This interpretation is

nevertheless plausible when unit 22 is placed together with the two units that

would have surrounded it, had the composer not eliminated them late in the

compositional process. The reader will remember that Nono cut the last 18 bars

of section ‘a’ of Part III. In these bars the soprano solo was to have sung the

text fragment “faremo luce al giorno” [we will shed light on the day]. The

pitches Nono used to set the soprano’s text can be seen in the following plate,

(see Plate 4) which presents a close-up shot of a portion of the sketch: E

flat, A, C sharp; B, F; E, B, B flat. All of these pitches can be derived from

the scale on F. They constitute seven of the eight pitch classes of the scale

and the E flat corresponds with Nono’s idiosyncratic manner of writing the

sixth degree of the scale: E flat instead of D sharp.

Example 7: Quando stanno

morendo, Part III, Finale, Compositional Unit 22 Plus Two Compositional

Units Eliminated by Nono, Placed Over the F Transposition of the

Scala Enigmatica, Transcribed From a

Sketch for Prometeo. All eliminated pitches are shown in parenthesis.

Plate 4: Quando stanno morendo, Part

III, Finale, Detail From the Sketch Presented in Plate 2.

Reproduced with the kind permission of the Archivio Luigi Nono. © Eredi

Luigi Nono

The point is not to

criticize or even question Nono’s decision to cut this section of the Finale (any

discussion of that lies outside the framework of this paper). However it is

interesting to note that the compositional units that were eliminated reproduce

the patterns of selection and organization that clearly dominate the pitch

structures of the first twenty-two compositional units of the Finale.

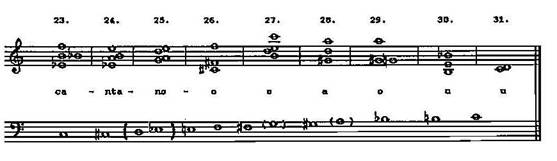

Units 23

through 25 set the last word of the text (“cantano”) and are different from the previous compositional units in two

ways. First, as tetrachords they thicken and enrich the harmonic texture by

allowing all four voices to sing simultaneously for the first time. Second from

unit 25 onwards, the pitch content differs significantly from that which

dominated the first fifteen compositional units. This can

be seen by comparing the pitch content of units 1 through 22 to that of units 23 through 31. As noted above, all pitch classes in units

1-22 are derived from the transposition levels of the scala enigmatica

on B flat and F. Together these two transpositions form a collection of 10 pitches:

the absent notes are C and G. Nono also systematically avoided using F sharp

(present both in the B-flat and F transpositions of the scale) throughout the

first section of the Finale (units 1-22).

All three pitch classes are deployed in the compositional units of the

last section of the Finale (units 23-31). Of the nine compositional units, five

contain one of the three pitch classes absent in the first 22 compositional

units. If we include the two compositional units Nono eliminated (see Plate 2),

the proportion remains approximately the same: six of eleven units contain

those three pitch classes.

The last nine compositional units are difficult to classify in terms of

transposition levels. On the one hand, these units contain all twelve pitch classes

of the chromatic scale. The units can of course be derived from various

transposition levels: notably on F (units 23, 24, 30); C (26, 30), C sharp (26,

27), F sharp (27, 31), and G sharp (25, 28, 29). However, no coherent grouping

similar to that found among units 1-22 can be achieved. An examination of the

spelling of this pitch class material reveals that it tends to correspond with

Nono’s idiosyncratic habit of writing the C transposition of the scale. (In his

sketch for Prometeo he uses C sharp instead of D flat and B flat instead

of A sharp.) Also C is prominently deployed as the highest pitch and as one of

the last two pitches. However, only two units (26 and 30) can actually be

derived from this transposition level and so though the idea that Nono was

working with a chromatically enriched C transposition of the scale seems

tempting, such an interpretation is inconclusive (see Example 8).

Example 8: Quando stanno

morendo, Part III, Finale, Compositional Units 23-31 Placed over the

Chromatic

Scale Based on the C Transposition of the Scala Enigmatica as

Spelled in a Sketch for Prometeo.

In order to reinforce the proposed segmentation of the Finale’s pitch

structures, we shall now turn to version 2. As noted above Nono reordered the

compositional units of version 1, creating a new version intended to set the

opening lines of Khlebnikov’s text. In version 2, two compositional units (23

and 24) are missing. Otherwise the pitch content and register deployment of the

compositional units in version 2 is identical with that of version 1. These two

versions also present a number of striking similarities in the manner in which

the compositional units are combined (see Example 1 above).

1 The division established in version 1 between compositional units 1-22

(derived primarily from B-flat and F transposition levels) on the one hand and

units 23-31 (which show no grouping according to transposition levels) is

clearly maintained in version 2. Nono used compositional units 25-31 to

complete the Finale. Indeed, the contrast between compositional units 1-22 and

25-31 is heightened in version 2. The compositional units 23 and 24, which begin the last section of version 1, can

also be derived from the F transposition of the scala enigmatica. In

version 1 they could thus be related to compositional unit 22, creating a

transitional or pivotal group between the two sections of this version. No such

transition exists in version 2. With its prominent C, compositional unit 27

makes a clear break with the preceding units.

2 More often than not,

words and musical phrasing coincide with groups of compositional units derived

from a specific transposition level. In version 1 only the first word of the

text (“Quando”) does not. To set this word, Nono used six compositional units,

divided equally into two groups of three: the first clearly derived from the

B-flat transposition and the second from F. This occurs twice in version two

(see the words “intristiscono” and “i cavalli”). Nevertheless, throughout these

two sections convergence of text, musical phrasing and compositional groups

constitutes the rule rather than the exception.

3 The patterns of grouping

identified in version 1 tend to be replicated in version 2. For example the first

fifteen compositional units of version 1 form a subsection by virtue of the

fact that they are encased in mirror relationship (see Example 1 above). No

such mirror relationship obtains in version 2. However the first fourteen

compositional units can be seen as forming a subsection bounded by groups

derived from the B-flat transposition level. Within this subsection similarity

also prevails. Certain groups from version 1 are maintained intact in version

2. Compositional units 7 through 9, which were said to derive from the E flat

in version 1, remain together in version 2, reinforcing the argument that they

do indeed constitute a group.

Notwithstanding the inconclusive analytical results concerning units

23-31 of version 1, Nono clearly reserved a different configuration of his

pitch material and a different end.

The structure of the Finale reminds us of comments Guerrero made on those of

Sarà dolce tacere and Cori di Didone (see above). Here too, the

clear, calm, homophonic structures of the a cappella chorale provide fitting

closure, both in terms of form and of content.

Furthermore,

by singling out the vocal material of Parts II and III to compose the Finale,

Nono is not simply constructing a logical end to a closed form; he also appears

to be using musical means to make an indirect commentary on the work’s content.

“Cantano” means ‘they (the men who are dying) sing’ and suggests that Nono set

the songs of dying men on another musical plane, creating an uncanny allusion

to the last twenty bars of Arnold Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw in

which the chorus of condemned men break out in song. Rather than continuing to

circulate along the well-trodden paths of previously composed material, this

last song breaks out into new uncharted territory. It is here that Schoenberg’s

two categories of knowledge about music (how it was made and what it is) meet

and interact in Quando stanno morendo.

Concluding Remarks

Among the sketch material conserved at the Archivio, I have not come

across any documents explicitly confirming that Nono consciously used

transposition levels of the scala enigmatica to organize the pitch

structures of the Finale of Quando stanno morendo. But then one rarely finds

smoking guns in archives and libraries because sketches are by their very

nature incomplete. Pascal Decroupet has astutely observed:

They are

the result of a process and not just evidence of a journey. In and of themselves,

sketches are incapable of revealing all of the stages linking the material and

the work. However through careful observation one can extrapolate, generalize

and even invent fundamentally important criteria, which may have left no trace

in the composer’s working documents. The analyst must therefore fill in the

blanks and engender coherence¼ If the

archaeological reconstruction of the composer’s thinking is by its very nature

an illusion, careful study of sketch material can endow the analyst’s hypothesis

with a certain degree of probability.

The above

citation brings us back to the point made by Borio at the outset of this

article. The information concerning palindromes, the symmetric relationships in

terms of register among compositional units and even the use of specific

transposition levels of the scala enigmatica to structure pitch content is of course all in the score to be

uncovered. But these relationships have to be identified among the multitude of

all possible relationships that can be produced from the data at hand, and more

importantly, the analyst has to be alerted to the significance these structures

can have for his or her object of study. The fact that Nono composed the vocal

material of the second movement in the form of a palindrome and then partially

obscured this structure in the Finale through the elimination of certain units

and the modification of pitch and register in others is important and can be

best apprehended from the study of his sketches. It is in this regard that the

study of the composer’s working documents is useful. As well as providing

quantitative information, which may not be otherwise available (i.e.

information gleaned from a comparison of versions 1 and 2 of the Finale), they

also enable the scholar to construct a qualitative environment within which he

or she can better validate the interpretation of analytical data.

Bibliography

Albèra, Philippe ed. Luigi Nono, Programme for Prometeo Tragedia

dell’ascolto

(Paris: Contrechamps/Festival d’automne, 1987).

Arnold, Denis. [Preface], in Giuseppe Verdi, Quattro Pezzi Sacri

(London: Eulenburg,1973)

Borio, Gianmario. “Sull’interazione fra lo studio degli schizzi e

l’analisi dell’opera,” La nuova

ricerca sull’opera di Luigi Nono, Gianmario Borio, Giovanni Morelli and Veniero Rizzardi eds.

(Venice: Leo S. Olschki, 1999).

Breuning, Franziska. Luigi Nonos Vertonungen von Texten Paveses (M_nster: LIT, 1999).

Cacciari, Massimo ed. Luigi Nono: Verso Prometeo (Milan: Ricordi

1984).

Campbell, Roy. Lorca: An Appreciation of His Poetry (New Haven:

Yale University Press, 1959).

De Benedictis, Angela Ida and Veniero Rizzardi eds. Luigi Nono

Scritti e colloqui, Volumes

1&2 (Lucca: Ricordi, 2001).

Decroupet, Pascal. “Floating hierarchies: organization and composition

in works by Pierre

Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen during the 1950s,” A Handbook to

Twentieth-Century

Musical Sketches, Patricia Hall and

Friedemann Sallis eds. (Cambridge:Cambridge

University Press, 2004), 146-160.

Dress, Stefan. Architektur und Fragment: zu späten Kompositionen

Luigi Nonos

(Saarbrücken: Pfau, 1998).

Feneyrou, Laurent ed. Luigi Nono Écrits (Paris: Christian

Bourgois, 1993).

Forte, Allen. The Structure of Atonal Music (New Haven: Yale

University Press, 1973).

Guerrero, Jeannie. “Multidimensional Counterpoint and Social Subversion

in Luigi Nono’s

Choral Works,” Theory and Practice 28 (2003): 53-77.

______________. “Tintoretto, Nono and Expanses of Silence” unpublished paper

presented at

the Dublin International Conference on Music Analysis, University

College Dublin, 2005.

Hall, Patricia. A View of Berg’s Lulu Through the Autograph Sources (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1996).

Haller, Hans Peter. Das Experimentalstudio der Heinrich-Strobel-Stiftung

des Südwestfunks

Freiburg 1971-1989. Die Erforschung der elektronischen Klangumformung

und ihre

Geschichte, Vol. 2

(Baden-Baden: Nomos, 1995).

Mazzolini, Marco. “Problematiche editoriali in Quando stanno morendo.

Diario polacco N. 2,”

unpublished paper presented at a conference entitled “Problemi

critico-testuali nelle edizioni

dell’ultimo Nono” organised by the Biennale di Venezia (June 1993).

Metzger, Heinz-Klaus. “Wendepunkt Quartett?” Musik-Konzepte Luigi Nono

20 (1981): 93-112.

Nielinger-Vakil, Carola. "Quiet Revolutions: H_lderlin, Fragments by Luigi Nono and Wolfgang Rihm."

Music & Letters 81/2 (May 2000): 245-274.

Nono, Luigi. Quando stanno morendo Diario polacco no 2,

André Richard and Marco Mazzolini

eds. (Milan: Ricordi, 1999).

Ogburn, David, “‘When they are dying, men sing ...”“ Nono’s Diario

Polacco n.2,” Ems:Electro-

acoustic Music Studies Network - Montréal, 2005, http:/www.emsnetwork.org/article,php3?id_article+175 .

Pestalozza, Luigi. “Nono, parole e suono”, Luigi Nono Scritti e

colloqui, Vol. 2, Angela Ida De

Benedictis and Veniero Rizzardi eds. (Milan: Ricordi, 2001), 603-630.

Sallis, Friedemann. “Le paradoxe postmoderne et l’œuvre tardive de Luigi

Nono,” Circuit

musiques contemporaines, Analyses 11/1 (2000): 69-86.

Schoenberg, Arnold. Letters, Erwin Stein ed., Eithne Wilkins and

Ernst Kaiser trans. (New

York: St. Martins Press, 1965).

Solare, Juan Maria. “¿Donde estas hermano?: Die ewige Utopie. Die

politische Haltung Nonos

nach dem Streichquartett und seine Auseinandersetzung mit

Lateinamerika,” Klang und

Wahrnehmung. Komponist – Interpret – Hörer, Darmstädter Beiträge 41 (Mainz:Schott, 2001), 215-248.

Spree, Hermann. “Fragmente – Stille, An Diotima” Ein

analytischer Versuch zu Luigi Nonos

Streichquartett (Saarbrücken:

Pfau,1992).

Stenzl, Jurg. “Gli anni Ottanta,” Nono, Enzo Restagno ed. (Turin:

EDT, 1987), 206-226.

Umbral, Francisco. Lorca, poeta maldito (Barcelona: Editorial

Planeta, 1998).

This article is an amalgamation of two conference papers: 1. “Sketch

material and the study of late twentieth-century music: the case of Luigi

Nono’s ¿Donde estas, hermano? (1982)” presented at a meeting of the

American Musicological Society (New England branch) held at Harvard University

on February 5, 2005; 2. “Segmenting the Labyrinth; Sketch Studies and the scala

enigmatica in Luigi Nono Quando stanno morendo. Diario Polacco N. 2

(1982)” presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory held at

Cambridge (Mass.) on November 13, 2005. I would like to thank the Social

Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Faculté des études

supérieures et de la recherche of the Université de Moncton for funding the

costs involved in this project. I am deeply grateful to Erika Schaller and the

Archivio Luigi Nono for providing timely support and assistanceand to Carola Nielinger-Vakil for her honest and helpful comments on this

text. I am indebted to Marco Mazzolini (BMG Italy) and

Jeannie Guerrero (Eastman School of Music, University of Rochester) for sharing

unpublished papers on their research with me. I also heartily thank my numerous

student assistants (Renée Fontaine, Rémy Fortin, Frederic Hétu, Sylvie LeBlanc

and Nicholas Smith) who worked with me in the course of this project. Finally I

warmly thank my colleague, Edward Jurkowski (University of Lethbridge) for his

thoughtful help and advice.

Federico García Lorca, Romance de la Guardia civil española

(1926) (last four lines of the poem)

¡Oh, ciudad de los gitanos! O

city of the gipsies, who

¿Quién te

vió y no te recuerda? That saw you could forget you soon?

Que te busquen en mi frente. Let them seek you in my

forehead.

Roy Campbell, Lorca: An Appreciation of His Poetry (New Haven:

Yale University Press, 1959), 78.

14 For a discussion of

certain aspects of the first movement involing an examination of sketch

material, see David Ogborn, “‘When they are dying, men sing...’: Nono’s Diario

Polacco n.2, “ EMS: Electro-acoustic Music Studies Network - Montréal ,

2005, http://www.ems-network.org/article.php3?id_article=175.

The other three works are Das atmende Klarsein for bass flute,

chamber choir and live electronics (1981); Io, frammento dal Prometeo

for three sopranos, chamber choir, bass flute, contrebass clarinet and live

electronics (1981); Guai al gelidi mostri for two contraltos, flute,

clarinet, viola, violoncello, double bass and live electronics (1983).

According to Hans Peter Haller (the inventor of the Halaphone and one of Nono’s

principal collaborators at the Strobel Foundation) the group of four works

should be seen as steps toward Prometeo. Tragedia dell’ascolto for

soloists, chamber choir, chamber orchestra and live electronics (1983-86), the

major work of Nono’s last decade. Hans Peter Haller, Das Experimentalstudio

der Heinrich-Strobel-Stiftung des Südwestfunks Freiburg 1971-1989. Die

Erforschung der elektronischen Klangumformung und ihre Geschichte, Vol. 2

(Baden-Baden: Nomos, 1995), 127-128. To the above list one should also add Omaggio

a György Kurtág for alto, flute, clarinet, tuba and live electronics

(1983-86).

20 Email received from

Carola Nielinger-Vakil on 14 February 2007. See also Fanziska Breuning, Luigi

Nonos Vertonungen von Texten Paveses (M_nster: LIT, 1999), 246-247.