Language and Percussion: An Actor's

Perspective

Wendy Salkind

Stuart Smith's music covers a wide range of styles, yet underlying all

the works is his deep commitment to improvisation. As in jazz performance,

he seeks a composer/performer collaboration, writing

scores that invite the performer to improvise a tempo, the

duration of a silence, entrances of the materials. Whether it

is his instrumental compositions or unsung vocal pieces, he writes

with a fascination about the performance process. Thus,

many of his pieces are written to be performed by a musician or by a singer, dancer or

actor.

Smith, in a discussion of

his childhood training as a percussionist, describes the human voice as a drum.

As a kid I was never

taught to sing pitches. I sang rhythms. There was a palpable, inevitable connection made

between language and rhythm.1

Much

of his compositional process developed from this early, visceral knowledge

of the rhythmic rather than semantic or sonic value of words. A group of his

compositions, which he calls speech songs, are spoken, and demand of the performer that the work or phrase be

experienced and performed through an

emphasis on the inherent internal rhythms. He creates those rhythms not merely with syllabic weight in a word, but through

a variety of speeds, durations, articulations and contrasts of long to short

vowels.

The textual source for these pieces is everyday speech. It is the familiar,

often banal language spoken in the home and on the street. Yet he

juxtaposes words in such a way that their sonic qualities and semantic value

are no longer familiar to the listener. The words require reinterpretation. Smith

says:

If nothing

more, speech songs are a reminder that language is invented by us and if we are not careful it

totally invents us without our awareness or control. Composing in words helps

us regain control . . .2

Regaining that control is quite different from the

actor's vocal process. An actor's training

strives for a refined sensitivity to the exprE4siveness

of words. Language is rich not only for its sonic value but because it defines

past experience or exposes spontaneous experience. Linguistic imagery is often

psychological in nature, and actors must learn to express language through their sensory knowledge of the world. They study language to know the emotional value of sounds.

For example, actors learn that certain

large, open vowels, such as AH, OH, OO, when spoken, resonate deep in the body.

The physical sensation of speaking those sounds so that they resonate

fully is subtly linked to a psychological experience.

In voicing them, one feels large, powerful, sexual, vulnerable, and rooted in the chest, the belly, the groin.

Obviously, not all words holding

those vowels have meanings that parallel the sensations I have described. But the actor, like the singer, knows

that a good writer/composer will

expose the heightened emotions of a character through language whose sounds trigger the actor's psyche and allow the voice to wail, sigh, or sing. Although the voice

can also be strident or crisp, the

actor learns that the voice is an extension of the breath, and as such it is a release of self. For the actor the voice is a

musical instrument with lyrical powers, and is rarely conceived of as a

drum.

What Smith asks of his performers, then, is that

they learn his texts first as rhythmic scores, rejecting any personalization of imagery, and gradually allow those rhythms to inform the sonic values, of

the language. This process, although not

intellectual, is not solely sensory,. but it is a process in which the

performer must externally observe her or his own internal experience of performance. In other words, the performer cannot

unlearn a personal history of words as she/he

speaks them. But in performing them with an imposed

awareness of rhythmic value, the performer re-learns those words, and thus

creates new images. In order to achieve

Smith's desired results, this self-observation cannot lapse. The performer

must never become lost in the actor's sensory world.

That self-observation is a process that then

distances the performer from the audience and

demands that the audience not only observe language being performed as music, but observe the performer observing her or himself. The audience never relaxes back in their seats to listen,

but they too re-invent this seemingly

familiar vocabulary. They must learn to see that the performer is a vehicle for the text to play on the voice

and body, rather than an interpreter of the composition.

During my rehearsal period with Smith of a speech

song, Smith discovered the difficulty in maintaining this

performance technique of self-observation

and actually chose to incorporate vocal elements of characterization and of sonic imagery. Through

this article I will discuss the resultant performance process.

Commentary on Smith's Speech Songs

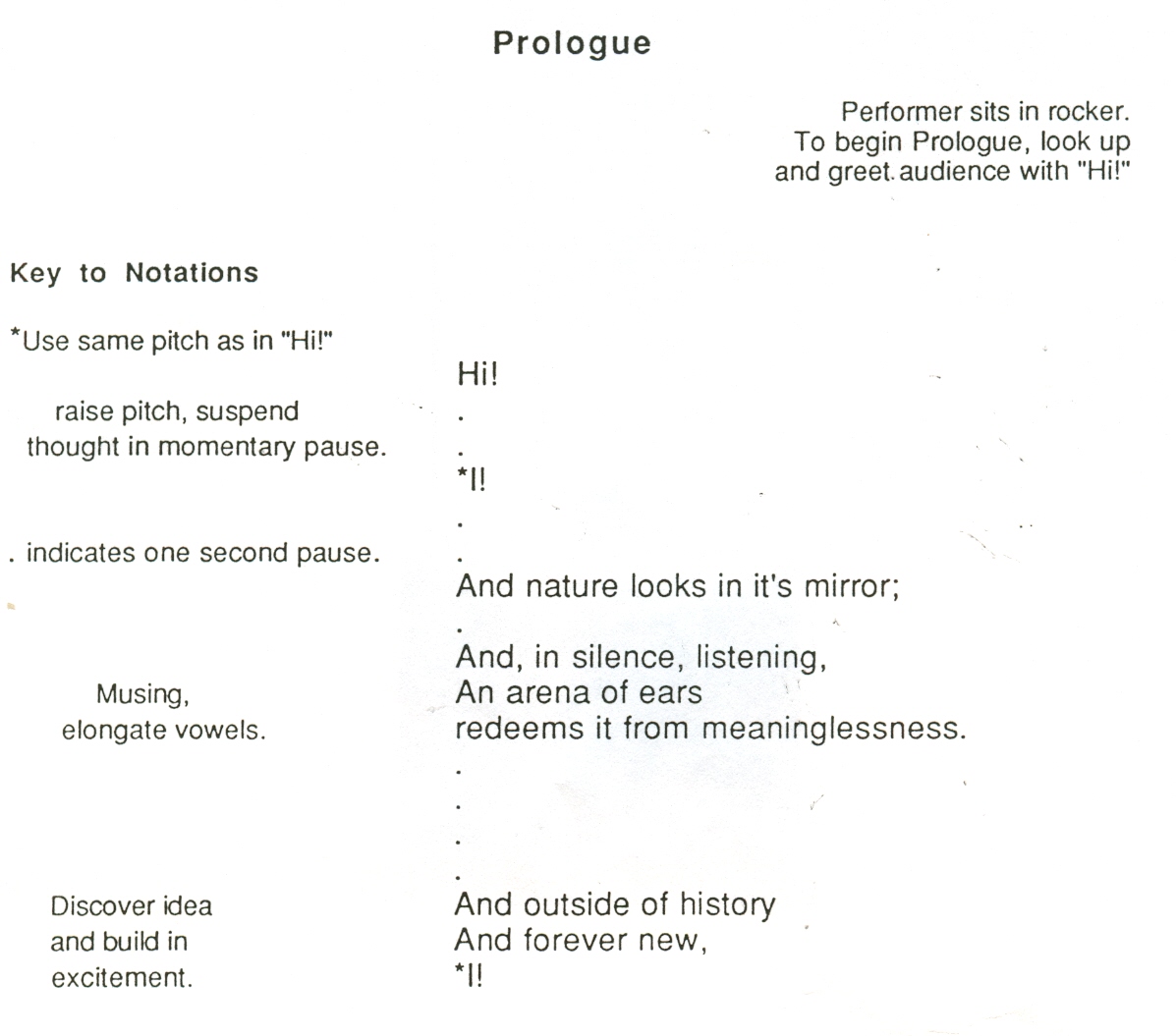

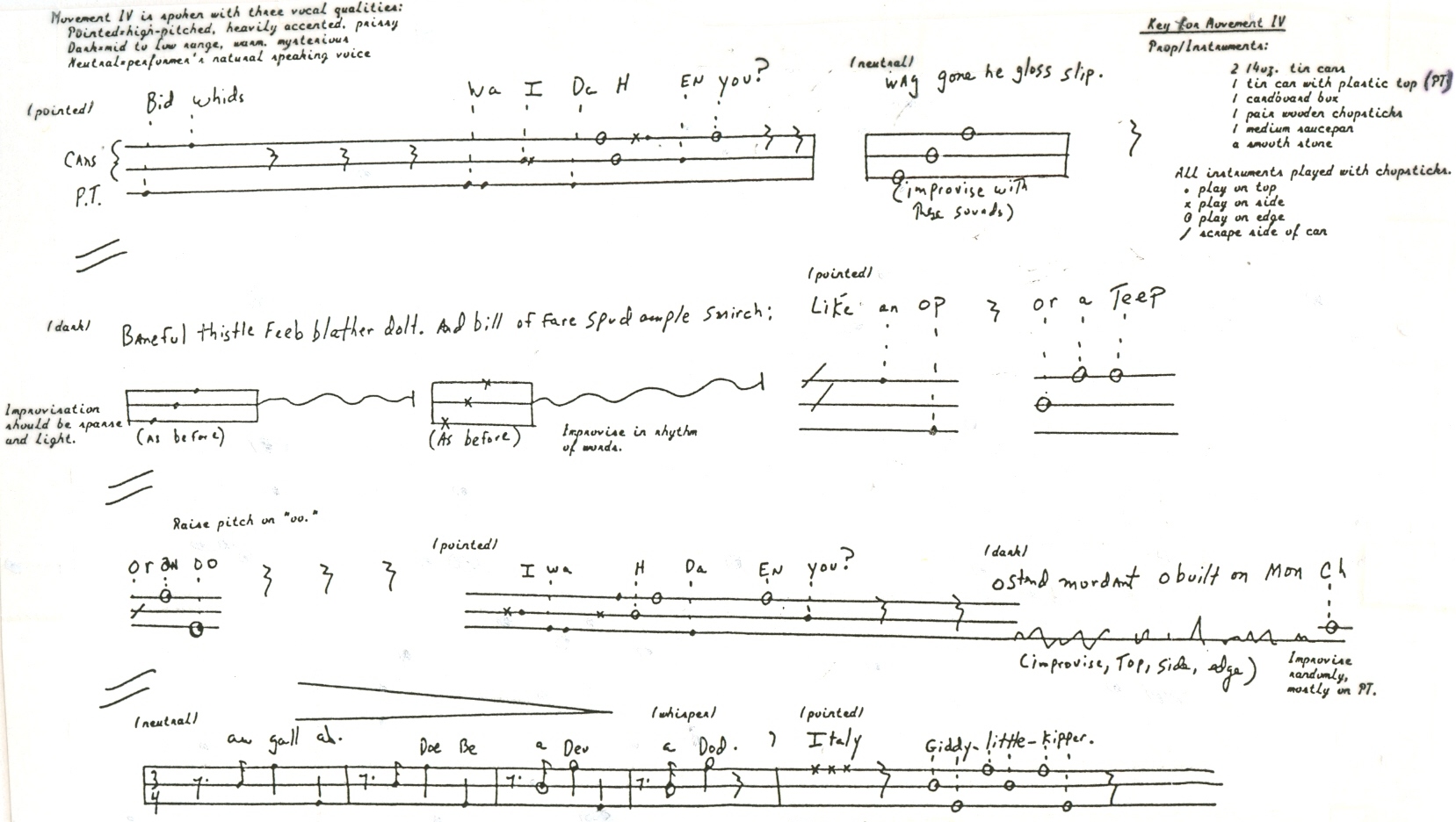

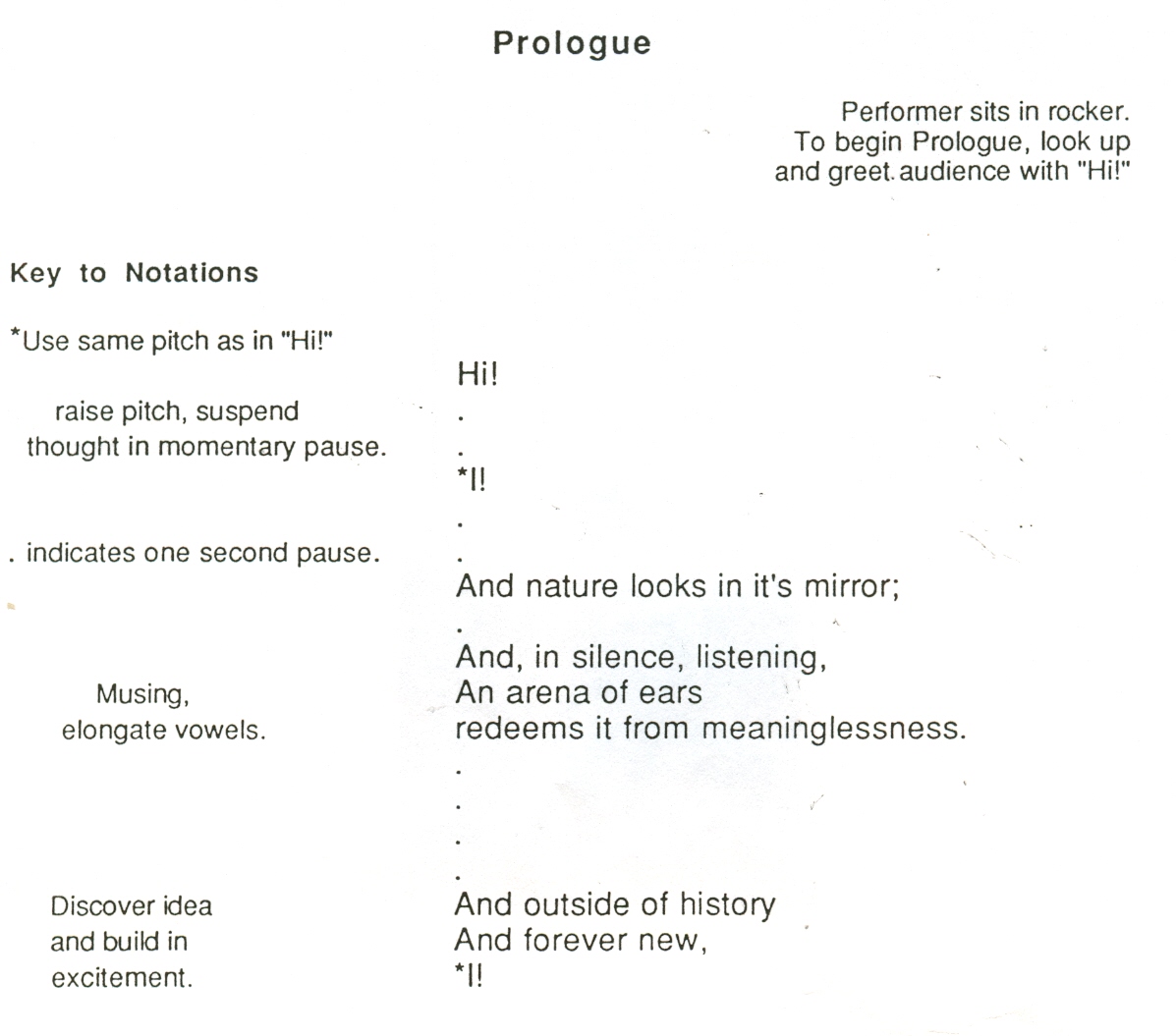

Smith's two solo works, By Language Embellished: I and Songs

I-IX, are compositions for speaking voice and percussion, which place common

words and sounds in an unusual context and set them, as text, against a percussion of household objects. By Language

Embellished: I, composed in 1984,

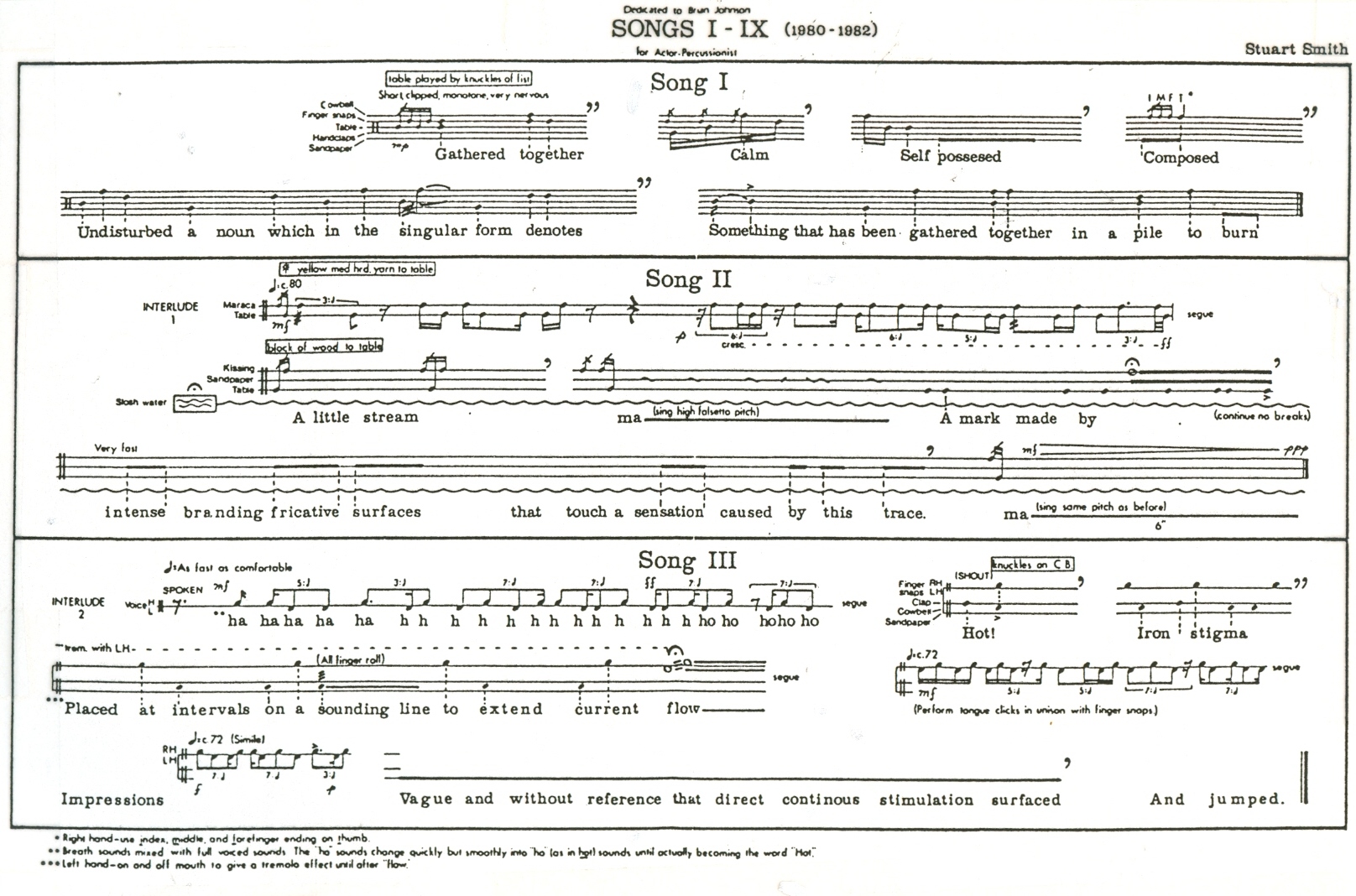

is a text that is often descriptive and poetic, but is at times non-referential when written as a cluster of nonsense

words (see Example 1). Some sections

of the text are simply monosyllabic sounds that are used primarily for rhythmic exploration and vocal

color. The composition is made up of a

prologue, four internal movements, and an epilogue. The Prologue and Epilogue are unaccompanied texts,

while the other movements all have percussion accompaniment of diverse

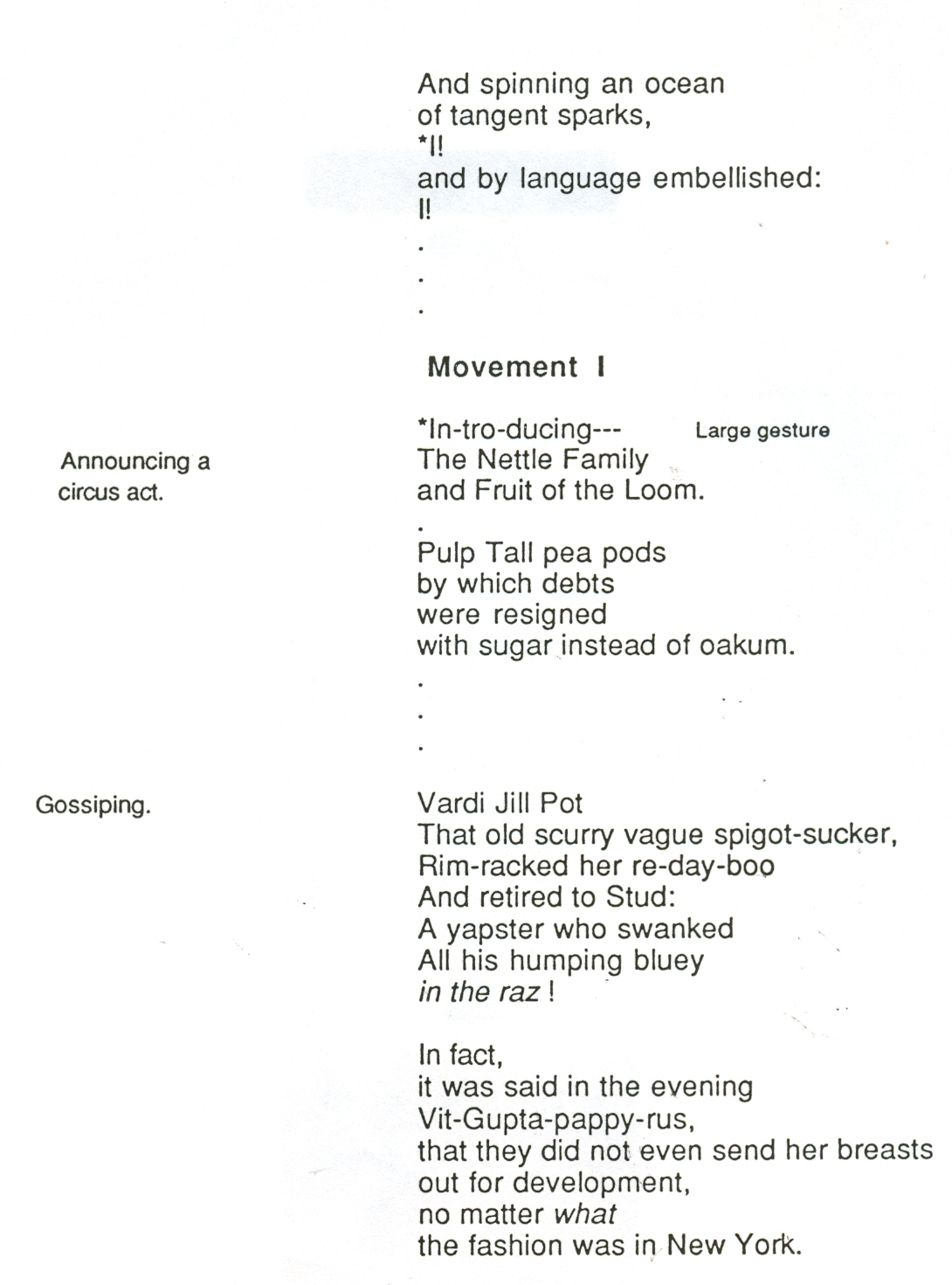

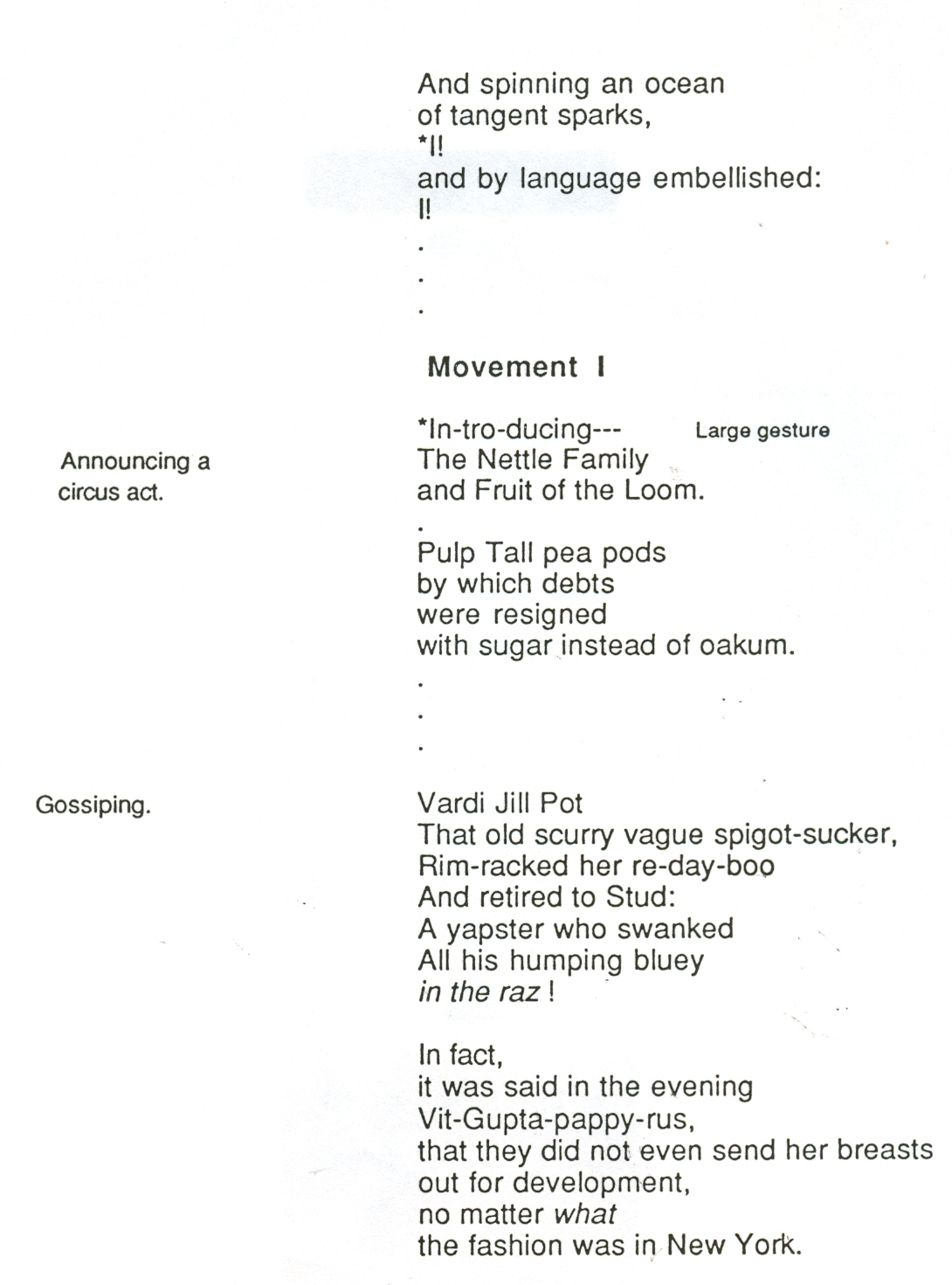

materials. For Movements the percussive

sounds are used intermittently, and are notated at specific places alongside the text. However, in the fourth movement,

the percussion (four metal cans struck by chopsticks) does not serve as an

accompaniment but plays continuously so that the voice and percussion form an

instrumental duet (Example 2).

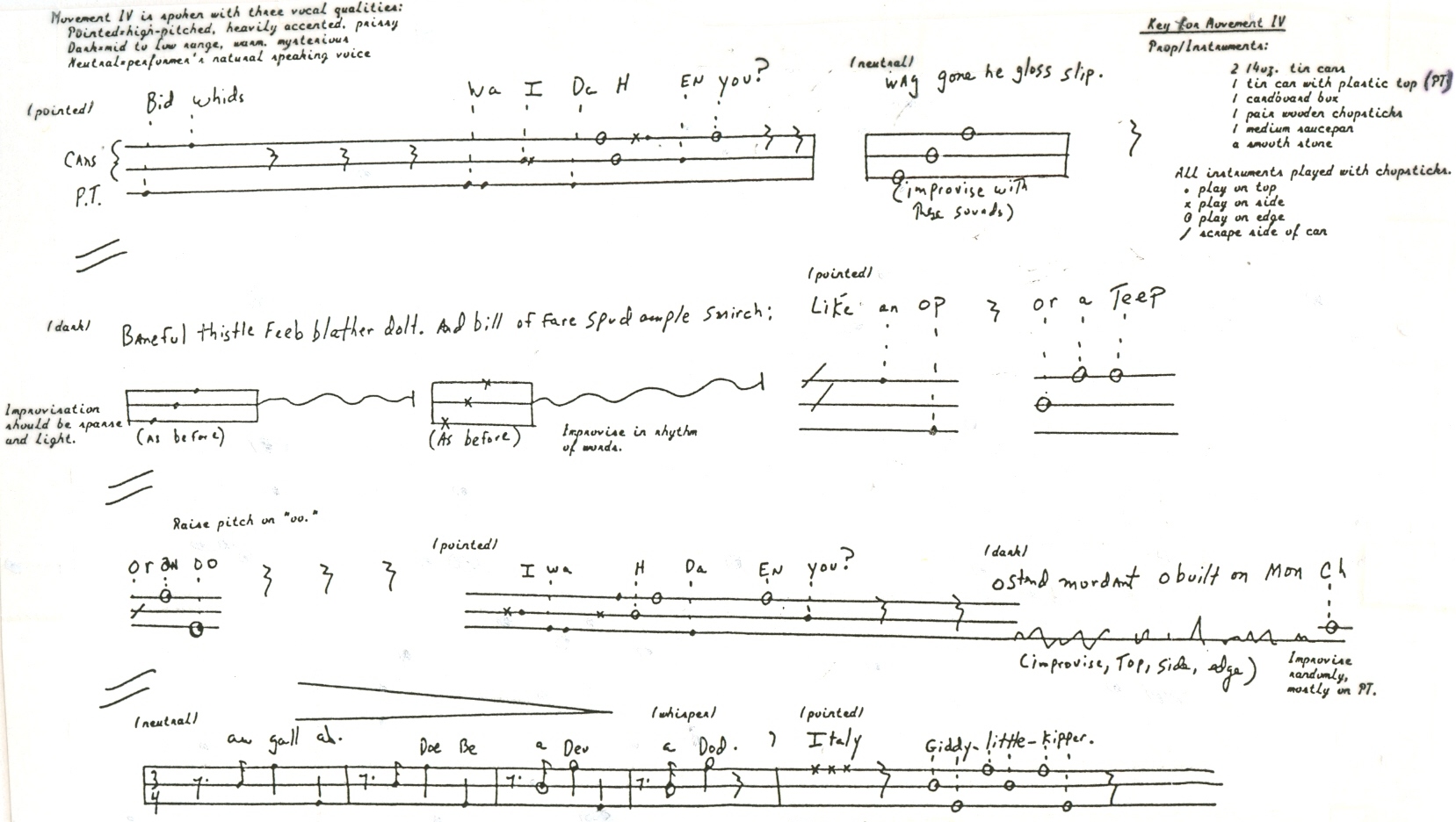

Songs I-1X, composed in 1980, differs from the later work in that it is not one long vocal text, but nine short texts, sometimes only two lines

in length. The songs are small poems where language is used metaphorically. In them, Smith relies heavily on onomatopoeia for vocal color, rhythm and for humor. All of the songs are spoken. The briefness

of the songs demands a driving intensity from the

performer, who must manipulate a large number of

percussive materials. Percussion ranges from the dry, crisp sound of rubbed sandpaper, or the harshness of a ratchet, to the

lush sounds of sloshed water- and strained delicacy of the scraped rims of

glass jars (see Example 3).

Interestingly, the tight structure of the texts

themselves is juxtaposed to the compositional

process Smith used to find a starting point for each work. That process was decidedly random. In other words, rather than compose the piece from a preconceived idea of what it should sound like or what the text might mean, he allowed his inspiration to come from capricious sources. He says that the origin of the words, "by

language embellished, I," was his

young daughter, who, having read them, taped them to the front door of their home. Similarly, the phrase,

"outside of history and forever new,"

seemed to jump off the page as Smith was reading the

poet Gary Snyder's discussion of the roots of American Indian poetry. Smith then used both these phrases to

generate the text of the Prologue of By

Language Embellished: I. He looked up the definition of each word in those two phrases and then found the

definition of all those words, until

he had compiled an enormous amount of material, from which he drew. Not

only were his sources of inspiration from found text, but he repeated this process so that all the

words and definitions from the Prologue

created the entire vocal text. For example, in researching the meanings of the word "ocean," he arrived

at the nautical terms he later usedin the third movement.

Hen-fruit

Hit the Jack

You, peakage,

Draw up the verbals!

Cut capers on a

trench!!

Amputate the mahogany!! 3

Some of the

expressions in the text are from the 18th century or from Australian slang. Smith took pleasure in writing a

phrase such as, "Floaters in the

snow," and having it sound like a Japanese haiku, when in old

England, it actually referred to food.

Example

1

His compositional method led to a text that is neither linear nor cumulative.

The placement of sections is unpredictable. One phrase does not

interpretively follow the next and often one metaphor has no relation to the poetic image which

preceded it.

Example

2:

By Language Embellished: I, MVT. I (solo version)

Example

3

This same process of found text generating more text, Smith practiced earlier in

writing the first three songs of Songs 1-IX. However, the middle three

songs, rather than come from definitions of the words of prior songs, were composed subjectively from sounds,

memories and visual pictures of his

imagination. Once again, with the last three songs, he relied on a

random structural technique although one that differed from the first described. He chose to make the linguistic meaning

of the text of Songs VII-IX an inversion of the meaning of

Songs I-Ill.

From Song I:

Gathered together Calm

Self-possessed Composed

From Song VII:

Grrah! Separately disquiescent

An aroused anti-signed nefariousing

Whippersnapper, noxiously

ne're-do-welled.4

Clearly,

the words in each song do not oppose each other in definition, but the

interpretive sense of the pictures they conjure up works inversely. One can

also see that the imagistic peacefulness of the first song is represented by

the sparseness of the words on the paper, whereas the harsh, biting character

of Song VII growls at length across the page. Songs I-IX contains many of the same

compositional structures as does By Language Embellished: I, but in the

latter work the techniques are more fully developed. For that reason, and because I worked directly with the piece,

I will continue to discuss

it-primarily, and make reference to Songs I-1X for the sake of

comparison.

The playfulness of Smith's discovery of text was reinforced by his choice

of percussive materials. Once he wrote the text and could hear it, he

knew the sounds and rhythms he needed to accompany it. In a process he

refers to as recycling sounds, he chose to use only those materials he could find in his own

environment. The third movement employs the widest range of percussive sounds. The instruments are: three metronomes set at different tempos, a typewriter, pennies in a

plastic cup that are poured into a

metal teapot, two pieces of sandpaper that are rubbed together, a chopstick inside a water glass which is trilled, a

saw blade which is drawn along the edge of a tin can, two radios set on

FM classical music and AM talk show, and a

pack of playing cards which is shuffled. In the fourth movement, aside from baby formula cans, the

percussive devices are a large cardboard box which is slapped and

trilled by hand, and a saucepan placed

upside down on which is rubbed a smooth stone. Had Smith composed the

work in some other place, surrounded by other objects and materials, his choice of percussive elements, and

thus, the texture of the sounds of the composition would have been

different.

In his introductory performance notes to By Language Embellished: I, Smith states,

"The music of the composition exists in the internal rhythms and timbres of the words."5 Yet in rehearsal, I found that it is

also the varied

uses and structures of language that direct the performer and, thus, the music.6 Both compositions demand that the

performer discover constantly changing strategies in order to realize

and communicate the text. I chose the role of a narrator when the text

was descriptive of visual pictures or experiences.

Having just reached the position

of a middle-aged

potato,

the new moon, threadbare,

renewed it's memory

by eating the

broth

with a complex

plot,

as the tiny Cone

of Sand

with it's needle leaves

and dark purple Amarillo restated

what has never been said:

If you stare like a fish

death is a white tie.7

In this role I

was a storyteller and, though I assumed no other persona, I spoke to the audience with

the awareness that these words were my own.

The

work often requires that the performer become a character and that the text become

personalized.

Hey, Chill Off!

What's a gentleman's companion anyway?

A pneumonia blouse

corrupting the color yellow?

A loose pavement stone

crushing in the bud?

Like

diamond sharks filling cavities

with a bellyful of marrow pudding?!

Hey,

Chill Off! 8

In

the above section, the character was a crass, nasal-voiced New York City

cabdriver, who was berating another driver who just rammed into her cab. When speaking as

this, or any of the characters in the piece, the vocal changes were heightened by facial expressions that emerged as an organic extension of the character transformation.

In this particular case, the

percussive accompaniment of a saw blade drawn across the edge of a tin

can intensified the characterization and vocal range.

Finally, I sought a performance style that would impose nothing on the

text. I call that condition, to which I often returned, neutral. It was a method

of performance in which there was no characterization, no embellishment

of referential imagery, merely a performance state in which the

sounds of the text played on the voice. When I was neutral, the language defined and

embellished me.

Space between,

difference, between;

here and there

A quantity of quick time

that has been or ever will be,

Often,

Large Commas,

Notwithstanding.9

Smith's most frequent manipulation of language is gibberish, or nonsense

language, where sounds are suggestive of actual words. Throughout this

text authentic words are set in the midst of gibberish to falsely suggest literal

meaning.

Yes,

I,

Dictus Roustabout

gawk yahoo gobs scad

souse mint;

hump jag turk

empt smear gelt,

uddles clover forlorn.10

Although

the words are not referential, the direction to the performer, to "recite

traditional wedding vows,"11 determines a context and an interpretation.

The above section was spoken as a young, innocent and sincere girl. In

theatre, gibberish is an improvisational technique used when

an actor is relying too heavily on the literal meaning of the words in the script. By speaking

gibberish, the actor is able to communicate deeper emotional levels of the character's actions. Smith does not use

gibberish to interpret any other text. Rather, he demands that the

performer create a meaning and context, or

simply allow the sonic value of the nonsense language to stand uninterpreted.

There are a number of passages which might be described as poetry.

In them language is metaphor, and creates visual and emotional imagery.

With

Anvil far back on night

came the breaded bone of Galilee

and straight

around the corner

He did the briny the mazy

and the Rose on oceandust,

and still the millstone

left a very deep

hollow

above His

collarbone;

For the Smith always had a spark

in his throat,

and anything too

deep

made the air blue in small tufts

for the light of the scorched.12

The

mention of Galilee and the capitalization of the pronoun, He, suggests a Biblical

story. There is also a delicacy to many of the images and a lyricism

to the whole passage. While rehearsing with Smith, I decided to extend these qualities so

that the section was performed as a narrator who, without using actual dialect, spoke in a warm, melodic voice, as though recounting an ancient Irish folktale. It is

primarily in these poetic passages that the imagery, more than the

sounds and rhythms of the words, leads the performer to the choices of vocal

color.

The second and fourth movements stress Smith's

usage of sound for rhythmic effect.

Pinoak Saltus

Azalea Cumber Pie.

.

.

.

Pre-name-clink-pokey-addle-denovo-vee-plus-ultra.

.

.

Andante.13

The

direction to the performer in this second-movement passage is to keep the text conversational,

without an attempt at interpretation. To do so, the performer must speak in the neutral voice. The section is sharply articulated with emphasis placed upon the short

syllables and elongated vowels. By minimizing inflection and strengthening the

articulation of the sounds, rhythmic value is heightened.

As is clear in many passages previously quoted, Smith explores humor by placing ordinary

words in an unusual context. Often he begins a sentence with familiar language,

in a familiar context, and then substitutes gibberish or inappropriate words. The syntax sets

up a certain expectation for the, listener, which is then

fulfilled in an unpredictable manner.

Feeling down in the trench?

.

Had your nose in iron parenthesis

for 31 days of late loan behind?

.

Add zest, by aging!14

The structure of the two

questions is a parody of hard-sell advertising. The performance notes reflect

this by stating that the performer should speak as though selling a product on a television commercial. What one realizes

is that by speaking the sentences as though they made sense, the humor is

accomplished. In Songs I-IX, Smith

uses this same technique and often relies

on visual gesture, (thigh and buttock slapping), for humorous effect. He also incorporates non-verbal sounds, such as

tongue clicks, growling and whistling, into the piece. These vocal sounds

demand that the voice function as an instrument of pure sound rather

than phonetic sound. In By Language Embellished: I, this technique, as a

source of vocal expressiveness, seems to be replaced by quick changes in

character voices.

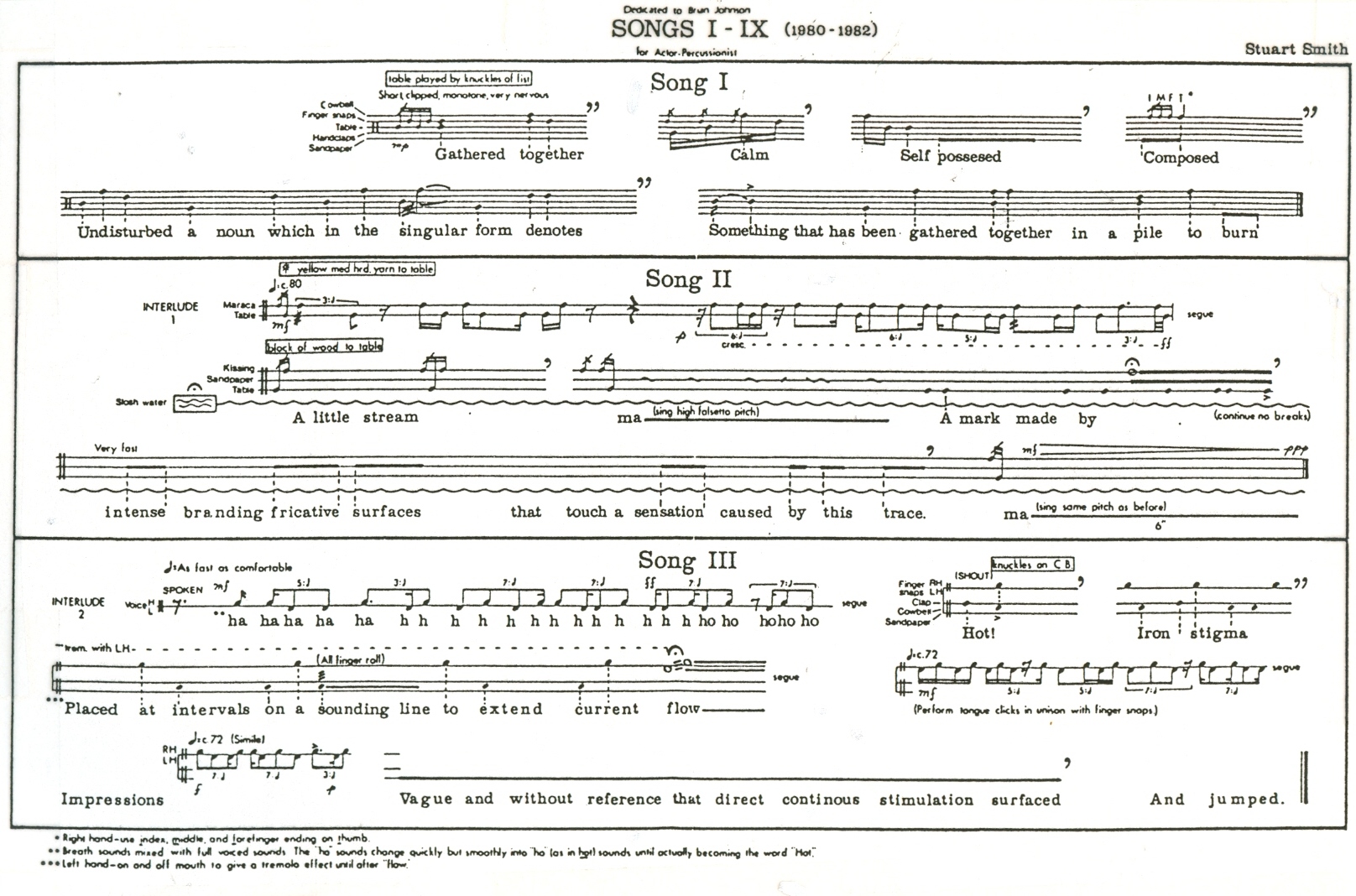

Characterization is most

extensive in Movement I and Movement III. Originally, Smith's performance notes

indicated such characters as the Schoolmarm,

the Sideshow Barker, the Gossip. In rehearsal, we

found that the problem with speaking the

text as a given character type was that the voice responded to a stereotyped image of that character. The words were diminished because the character was

generalized. To speak as a gossip

might imply a nasal-voiced, trivial woman. But to gossip is actually an activity that can bring one great pleasure. It

provides a way of discussing

experience through a vicarious re-living of another's actions. Once the composers markings were changed to indicate the actions of

the character, as in Gossiping, rather

than the character type, the voice responded

to genuine emotion (see the last section of Example 1). The words, whether nonsense or not, became

personalized and the voice responded accordingly.

Throughout

the composition the transition from one character to another and the tonal changes occur during a silence. In Songs I-IX, the

silences are notated as a short or long

pause. In By Language Embellished:

I, each silence is marked by a

specific number of seconds, lasting anywhere from one to twenty. I found

that even though the silences were set, the actual length of these transitions

was determined through my internal sense of

time. Often during performance, the seconds were stretched, sometimes compressed, dependent upon the emotional tone of the preceding character or the psychological

tension of the forthcoming passage.

Thus the value of the second was variable, but the number of seconds remained true to the composer's markings.

During a transformation from one

character to another, the silence served as a period of unmasking. That period of time would often be colored by adjustments in seating position, change in eye

focus, or physical gesture. For

rapid shifts of character, the silence became a breath, an expressionless

moment in which to refocus. At times, the silences were not transitional elements, but beats of their own.

They provided space within the sound, they allowed stillness for the

performer, and they extended the musical tension of the whole composition. The

silences became the text.

Along

with gibberish and poetry, characterization is another of Smith's powerful devices for producing a large rhythmic and sonic range. Movement III is dense with a variety of

characters, and the percussive elements,

rather than function only as accompaniment in that movement, often intensify the emotional content of the text.

When, in an early passage, I spoke as

a pre-adolescent boy selling newspapers on a street corner, I interrupted the text with loud bursts on

the radios. For the audience, the

radios created a busy street cacophony, while for me, as the boy, the

sound intensified my urgency to be heard and to make a sale. By comparison, the percussion in Song I-IX often

works directly against the meaning and tone of the textual image or the

vocal timbre. Looking again at the text of Song / (Example 3), the word

images are spoken in a "short, clipped,

monotone, very nervous" against an equally erratic percussion of table-, and hand claps, rubbed sandpaper, and a

ringing cowbell. The overall effect is that the words stand apart from

the percussion and the accompaniment seems to comment upon the meaning of the

words. In By Language Embellished: 1, the percussive elements usually complement and support the vocalization. In Movement IV (see

Example 2), the percussion of

chopsticks tapping tin cans, is a constant, primary voice while the performer's voice of often monosyllabic

sounds, subtly weaves in and out of the percussive line.

By Language Embellished: I was carefully choreographed through Smith's design of the physical set-up

of the performance. His subtitle for the composition is,

"An opera without singing in acts." By removing the singing or

music from the opera, one is left with words. One is also left with theater. The Prologue and Movement I are spoken

with the performer sitting in a

rocking chair. For the second movement, the performer stands. A twenty second silence separates the second and

third movements, during which time

the performer moves to a card table covered with the numerous objects discussed earlier. The performer

again crosses, for the fourth

movement, to a piano bench on which are placed the tin cans, chopsticks, a large cardboard box, and saucepan.

The Epilogue is spoken with the performer standing directly in front of the

audience. The chair and tables are

arranged in a semi-circle which opens toward the audience. This is clearly a stage set. The circular

arrangement and the furniture suggest

an intimate, home-like environment. Most of the percussive materials are household objects. The performer is

dressed in casual clothes: jeans and

a sweatshirt. There is a sense of improvisation, of play, as the performer moves-from one place on stage to

another. Yet the environment is not

suggestive of any specific place. Perhaps the set is meant to imply that the audience should feel

comfortable with the performance,

that everything they are about to hear and see is familiar to them, is

already a part of their daily lives.

As is Smith's preference, the opera was originally

performed with two other compositions. Pinetop, for piano,

preceded it as an overture, and Flight, for piano and flute, followed as, in Smith's term,

an afterture.15 There were no pauses

between the performances of the three compositions.

The musicians for Flight and Pinetop wore traditional black, formal attire, and were placed at opposite ends of

the stage, with the opera set down stage center. This arrangement

enclosed the visual picture and intensified the

intimacy of the opera. It was the seemingly casual and familiar environment of the opera that was the more

theatrical of the two worlds,

particularly as it was juxtaposed to the formal, but predictable, physical performance arrangement of the other two

pieces. With the later two compositions, the audience could close their

eyes and absorb the full impact of the music. The opera, however, needed to be

watched for the performer's characterization

and interaction with the objects were an integral part of the performance. They were the element of theater that heightened

the imagistic and sonic value of the text. At the same time, the visual picture of the opera challenged the

audience's perception of the other two compositions. That contrast between the

formal and informal created theatrical tension.

The performance of Songs 1-IX and By

Language Embellished: I is not limited to only

an actor or a percussionist. Each performer is challenged to

bring a different quality to the work that will effect the ultimate interpretation. While this is true of any

re-creative art form, it is particularly so in this case. The emphasis on ordinary sounds, both percussive and vocal, creates a wide base of shared

experience from which the interpretation can proceed. Common household objects

take on a rhythmic life, gibberish

acts as comprehensible language, cultural/linguistic cliches are sources of humor. Smith demands that both the

performer and the audience look at what is most familiar in their lives

and hear it anew.

1Smith,

at present writing from an unpublished manuscript.

2

ibid.

3Stuart

Smith, By

Language Embellished: I, unpublished manuscript,

performance notes by Wendy Salkind, 1984.

4Stuart Smith, Songs 1-1X, Sonic Art Editions, 1980.

5Stuart Smith, By Language Embellished : I.

6Smith and I rehearsed

By Language Embellished: I in August and September, 1984, for the

premiere performance in October, 1984, at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

7Stuart Smith, By Language Embellished : I.

8 ibid.

9 ibid.

10 ibid.

11ibid.

12 ibid.

13 ibid.

14 ibid.

15Pinetop

(1976-1977)

and Flight

(1977-1978),

published by Lingua Press, may be and often are performed as separate pieces in

the usual concert format.