Viktor Ullmann’s The Emperor of Atlantis (1943):

An Opera Composed in Terezin Concentration Camp

Robert Rollin

Victor

Ullmann was the oldest and perhaps the most influential of the four great

Czech-Jewish composers incarcerated in Terezin Concentration Camp. The others

were Hans Krasa, a student of Zemlinsky and Roussel; Gideon Klein, a student of

quarter-tone composer Alois Haba and a leading Prague piano soloist; and Pavel

Haas, a student of Janáček. All four perished

after transport to the death camps.

Born

January 1, 1898 in T.siÁ (Teschen)

on the Moravian/Polish border, the son of a high Austrian officer of noble

birth, Ullmann spent his early days in Vienna studying piano with Eduard

Steuermann and theory and composition with Arnold Schoenberg. He went to Prague

in 1919 under Schoenberg’s recommendation to be Alexander Zemlinsky’s assistant

conductor and piano accompanist at the prestigious New German Theatre. Among young the Ullmann’s colleagues were

Erich Leinsdorf and George Szell.

In

1929 Ullmann was appointed senior director at the Aussig Opera (Usti Nad

Labem), where he premiered Richard Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos, Krenek’s Jonny

Spielt auf, and other important operas. From 1930 he was a Czech Radio

commentator and music critic for major newspapers and music education

journals. At the same time he studied

quarter-tone composition with Alois Haba, but abandoned it after one piece for

clarinet and piano, and by 1942 he had composed four piano sonatas, two operas,

a piano concerto, and several song cycles.

Despite

his demanding career, Ullmann also managed to run an Anthroposophical Society

book store, and to direct the Zurich Theatre Orchestra; thus his pre-war life

was hectic and rather disjointed. After the crowded and perilous train ride to

Terezin, he soon undertook the directorship of the Terezin New Music Studio

Concerts and oversaw the various Terezin rehearsal schedules. He also served as

Ghetto newspaper music critic, writing some 27 reviews in less than two years.

The

threat of the transport to points unknown and the constant privation somehow

focused and settled him more than previously, and he became the most prolific

Terezin composer, writing his marvelous Third String Quartet, the opera,

The Emperor of Atlantis, three piano sonatas (the last of which includes

notes for transformation to a symphony) and several song cycles and choral

settings - a total of about 20 works in a scant two years.

The Emperor of Atlantis was among the most

important of Viktor Ullmann’s major Terezin works. Regrettably, when summer

1944 rehearsals were nearly completed, an SS delegation made a surprise visit

and cancelled the production because of its allegorical references to Hitler

and the World War. The one-act opera, scored for small orchestra, reflected

Terezin’s limited musical forces, and its instrumentation resembled

Stravinsky’s and others’ in the post World War I era. For Stravinsky and

Ullmann, both, severe economic and political problems prompted new small

combinations with single winds and available exotic instruments. Ullmann scored

for alto sax, banjo (changing to guitar), harpsichord (changing to piano), harmonium,

percussion, a small woodwind complement, one trumpet and strings, exploring

Kurt Weill’s coloristic world in a more experimental musical language.

Peter Kien, a poet and painter and 1941 Terezin detainee, wrote the libretto in which The

Loudspeaker’s opening prologue introduces the cast of the Emperor Over All,

Life, Death, Harlequin, a Drummer Girl, a Boy Soldier, and a Girl Soldier.

The

four-scene opera is about 70 minutes long, and begins with Life and Death

commenting on a world where existence is no longer satisfying, and death no

true release. Then Death decides to break his sword and not permit the unworthy

world final release. In Scene Two, the Emperor decides to condemn an attempted

assassin, but discovers that execution is not possible, and that his and the

enemy’s soldiers simply will not die. A Soldier Boy and Girl from opposing

sides meet in Scene Three, and discover that they are unable to kill each

other. Despite the Drummer Girl’s exhortations, they embrace and sing a duet

seeing a ray of hope in their adversity. In Scene Four, Harlequin, Death,

Loudspeaker, and Soldier Girl meet the Emperor.

Death says that dying can only resume if the Emperor is the first

candidate. The Emperor agrees. Death then takes him by the hand and, assuming the

aura of Hermes, leads him through a magic mirror to annihilation, as the others

sing a paean on Death’s release to the Lutheran chorale melody, Ein’ feste

Burg ist unser Gott (A Mighty Fortress is Our God).

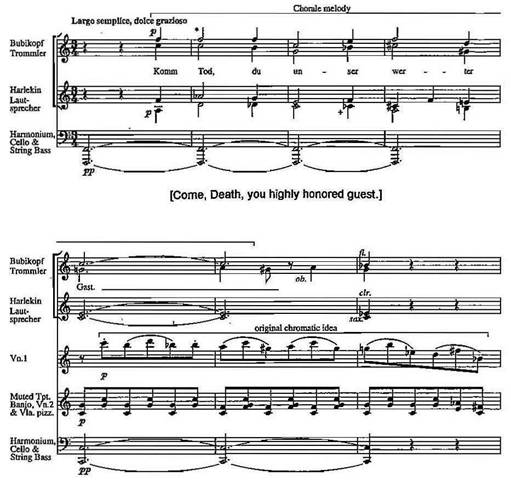

The

expressionistic opera shows the influence of Schoenberg, but the music is more

tonal and, like the Third String Quartet, reflects moderating French

influences and Kurt Weill’s dry wit as well. To start the finale of The

Emperor of Atlantis, Ullmann’s very literate background leads him to quote Ein’

feste Burg ist unser Gott, the chorale that J. S. Bach used in Cantata

No. 80 (the cantata employs the hymn tune in every single movement.)

Ullmann was well-educated in history and literature, and the pivotal presence

of Ein’ feste Burg very likely reflects more than simply the spiritual

resignation implicit in the text. It also connects with two works by two Jewish

predecessors: Felix Mendelssohn’s Reformation Symphony and Giacomo

Meyerbeer’s opera, Les Huguenots. Mendelssohn quotes the original

chorale setting in the stately introduction to the Andante fourth movement and

the chorale melody in dotted quarters against a syncopated six-eight

accompaniment in the ensuing Allegro

vivace. Meyerbeer opens his overture with the chorale, and further closes

his powerful second act ensemble with interjections sung from the chorale

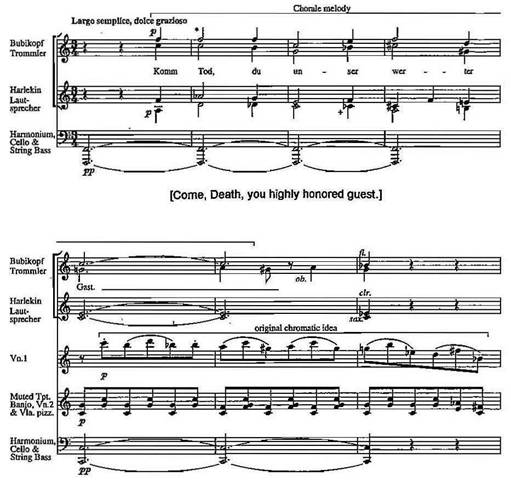

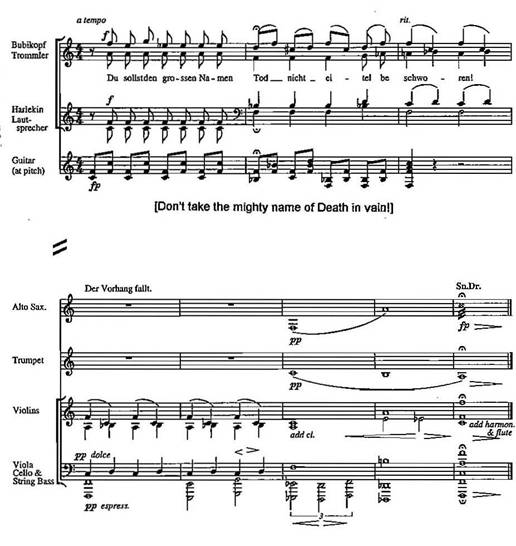

Example 1a: Ullmann, The Emperor of Atlantis. a. Finale, mm. 1-7

.** - pianissimo woodwinds freely double

voices from m. 2;

+ - should

probably be B flat,not C flat based on woodwind doubling

All reductions and translations by the author.

This and all subsequent reductions refer to

the full score, 1992 Schott edition.

Example

1b:

Emperor

of Atlantis Final 8 measures

Ullmann’s own

citation alludes to the futility of religious and political conflict throughout

Western history, and for the need to seek serious spiritual support and solace

in miserable, vicious times. Chorale phrases are presented with complex

neo-romantic harmony over pedal tones at the beginning of the Finale. Original

chromatic material (appearing first in violins 1) alternates with sung chorale

phrases (Example 1a). Later, the original chromatic material makes its way to

the vocal parts on the words, “You should not take the great name of death in

vain” (Example 1b).

Musical

paraphrase is endemic to serious music history in medieval and renaissance

cantus firmus compositions, baroque chorale preludes (not to mention Bach’s wholesale

citations and adaptations of Vivaldi), classical and romantic variation forms,

and many more. Ullmann, closely tied to Czech and Austrian music, begins his

opera with a musical allusion to the Asrael Symphony, Op. 27, by Josef

Suk (1824-1953), Dvorak’s son-in-law and an important Czech composer. The

symphony, composed in 1906 to mourn the deaths of Dvorak, and Suk’s wife,

Otilie, became a symbol for the First Czech Republic, 1918-38, and was played

on tragic national occasions. Suk’s death motive contains two ascending

gestures followed by a descending one. It first appears in a slow, diatonic

version and later in several more chromatic guises.

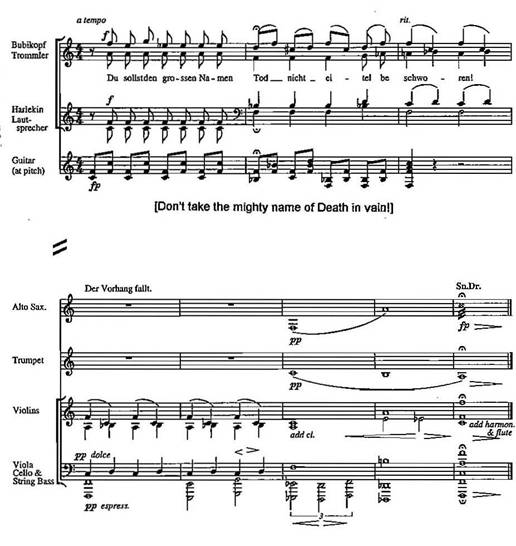

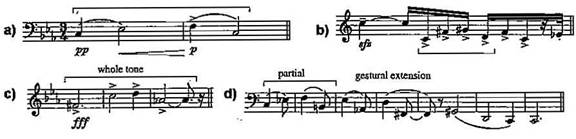

Example

2: Death Motive Versions, Suk’s Asrael

Symphony. a: mm. 3-4, bass clarinet, viola, cello (diatonic).

b. No. 7, strings (whole tone).c: No. 56,

winds (intervals as in b).d: No. 59 (partial with extensions).

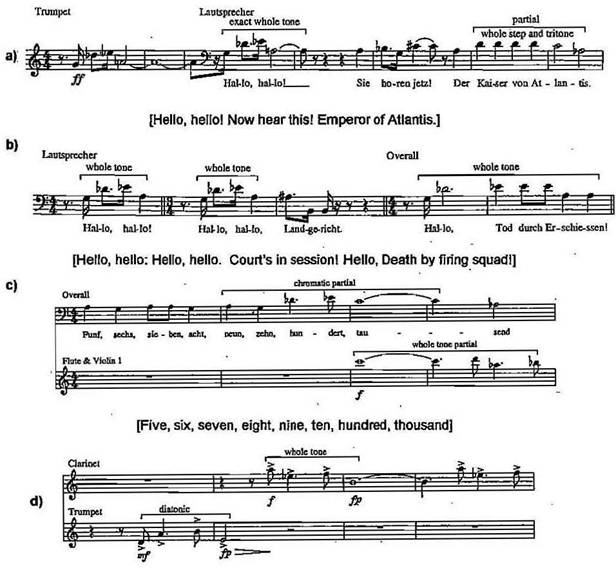

Ullmann uses the

chromatic version as an exhortation or call to attention at the very opening,

in other citations, and in gestural transformations:

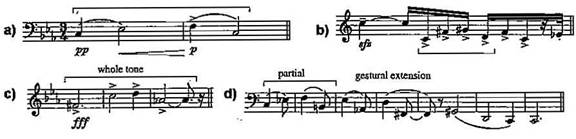

Example 3: Use of Asrael motive in Ullmann’s The

Emperor of Atlantis.

a. Opening of opera,

Prologue, mm. 1-7 (exact whole tone and partial whole tone statements).

b. Exact versions,

Scene II, pp. 61, 63, and 73 (whole tone)

c. Gestural, Scene IV,

No. XV, Quartet, p. 125, voice and flute/violin 1 (partial whole tone)

d. Gestural, Scene IV,

p. 130, trumpet, clarinet, voice (diatonic and octave-displaced whole tone).

The

opening Suk quotation and the closing Lutheran chorale help frame the opera

both emotionally and historically, and illustrate the composer’s nationalistic

pride, and bond with his musical predecessors.

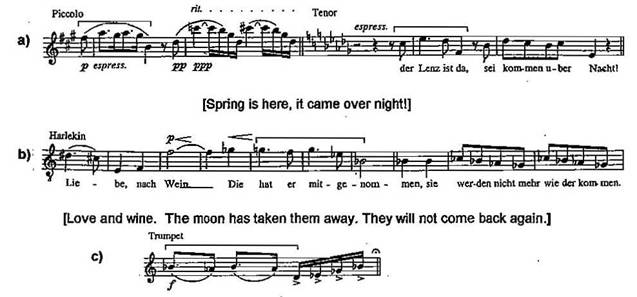

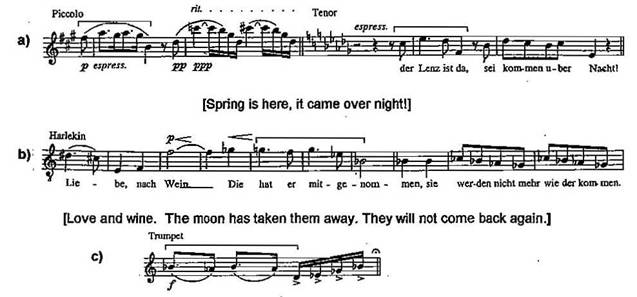

In

Scene 1, Section 3, Harlequin, who symbolizes benevolent and positive things,

presents rhythmic and melodic gestures from “The Drunken One in Spring,”

Mahler’s Song of the Earth, V, though Ullmann’s use is more

expressionistically Schoenbergian (Example 4a and 4b). A more subtle

instrumental reference takes place in the penultimate section, thereby framing

the opera with allusions to Mahler. This section also treats voice, solo oboe,

and strings canonically suggesting a Bach cantata texture. Soon there is a

change to a more disjunct melodic treatment reminiscent of “The Departure,”

Mahler’s Song of the Earth, VI, and, shortly thereafter, another

reference to “The Drunken One in Spring” (Example 4c).

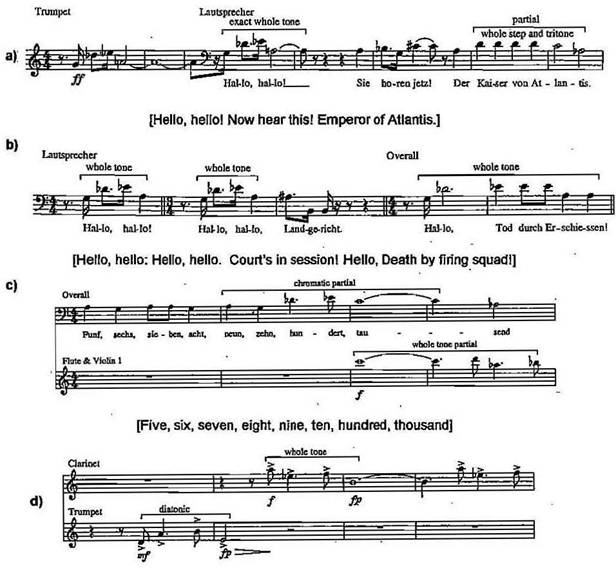

Example

4: Comparison of

Gestural Motives in Ullmann and Mahler

. a.

Mahler, Song of the Earth, “The Drunken One in Spring,” m. 43, piccolo;

mm. 52-4, voice part.

b Ullmann’s The

Emperor of Atlantis, Scene I, p. 6 - 7, voice part.

c. Ullmann, The

Emperor of Atlantis, Scene IV, p. 141, trumpet.

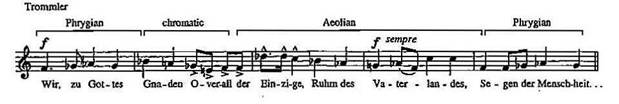

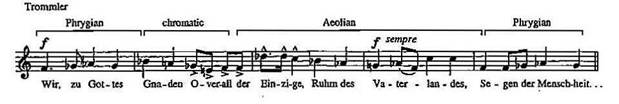

The sardonically

parodied tune, Deutschland Über Alles, exemplifies

yet another external musical source. Early in the opera, the Drummer Girl

loudly proclaims the Emperor’s call for “war of all against all” in which the

Nazi tune transformation appears in the first scene with Aeolian, Phrygian, and

chromatic melodic elements:

[We, in

God’s grace, Overall, the absolute, honored of the Fatherland, blessing of

humankind ...]

Example 5: Parody of Deutschland über Alles, Ullmann,

The Emperor of Atlantis, Scene I, p. 41.

Ullmann

bridges the gap between parody and the drama by using traditional formal

elements. He includes a passacaglia treatment in the Drummer Girl aria closing

Scene 1 to help portray Death’s relentlessness. Scene 2 is framed by an

instrumental Intermezzo marked “Tempo di Menuetto (Totentanz),” giving it an

arch shape. The death dance is, of course, a recurring nineteenth-century idiom

which often includes the ancient “Dies Irae” theme as in Berlioz’ “Witch’s Sabbath” in the Fantastic

Symphony and Liszt’s own Totentanz. Ullmann alludes to these works

in a stately parody minuet which never actually quotes the chant, but, hints at

it with stepwise melodic treatment and squarely-recurring phrasing. It is a

parodied dance of a death who has broken his sword, and who refuses to provide

sweet rest to a mankind capable of hideous atrocities. The minuet’s

strangely-mechanical quality is echoed in the loudspeaker’s sing-song and the

repeated announcements that “Death is expected at any moment,” when, in fact,

Death never arrives at all to take the condemned souls.

In Scene 3

a subdued instrumental cabaret-dance intermezzo punctures the intense

seriousness of the Boy Soldier and Drummer Girl love duet. Later, in Scene 4,

after Harlequin’s expressionistic exhortation to the Drummer Girl to sing

Death’s praise, and before Death’s final aria, Ullmann inserts a trio marked “Shimmy,” a dance popular between the

world wars (Hindemith used it in his Suite 1922, Op. 26 for piano.) The

Drummer Girl, Harlequin, and the Emperor, all sing different texts

simultaneously, not unlike similarly-situated passages in nineteenth-century

Italian comic opera. The bickering stops suddenly, and, as the instruments

continue, Emperor Over All uncovers a magic mirror and sees Death. As the

Emperor accepts his fate, the tragic mood resumes for the opera denouement.

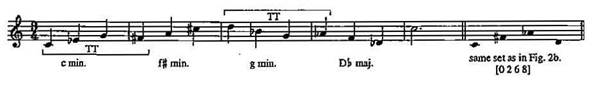

There is

much original material in The Emperor of Atlantis. In measure 24 of the

opening, Ullmann introduces an important and frequently recurring descending

chromatic motive. It appears throughout the Prelude coupled with a simple

accompaniment (Example 6).

Example 6: Original Chromatic Material with Pedalpoints,

Ullmann’s, The Emperor of Atlantis, Scene I, Prelude, mm. 1-8.

The tightly-constructed

motivic content and chromaticism point to Ullmann’s study with Schoenberg.

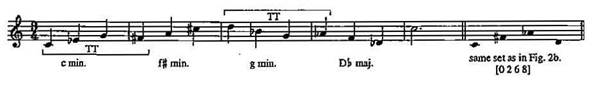

The

aforementioned Drummer Girl’s aria burlesquing Deutschland über

Alles

introduces a four-bar passacaglia theme praising death (Example 7). The

passacaglia amalgamates original and parodied material, and moves from voice to

instruments and back until interrupted by a recitative. The theme connects two triad pairs a tritone

apart, and, thus, freely derives itself from the original death theme. The

downbeats actually spell Suk’s whole-tone motive in free order and register.

The sets, mixing thirds and half steps, (see Example 7) are free references to

the aforementioned original chromatic theme (cf. Examples 6 and 7). These

sophisticated relationships show great skill and musical imagination, providing

one of the opera’s most powerful moments.

Example 7: Ullmann’s, The Emperor of Atlantis, Passacaglia

Theme, Scene I, p. 46.

More than

any other Terezin work, The Emperor of Atlantis embodies the struggle of

life and art against death, callousness, and deceit. Ullmann’s genius lies in his ability to

illuminate this profound-yet-tortured struggle, while interspersing cabaret

music, contrapuntal techniques, and references to themes by Czech and other

important musical forebears among his own vibrant musical ideas.