When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d

William

Pfaff

Roger Sessions'

cantata When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd was composed during the

years 1966-70 as a commission from the University of California, Berkeley.

The text of the cantata is Walt Whitman's elegy written in the months following

Lincoln's assassination on April 14, 1865.

By his dedication of the work to the memory of Martin Luther King Jr.

and Robert F. Kennedy, Sessions reflects the tragic events of his own time. In

the following passage compiled from the program notes, Sessions summarizes the

structure of the cantata:

The work is scored for soprano,

contralto, and baritone soloists, chorus, and large orchestra. It is divided into three sections, which

correspond to what seemed to me natural divisions of the poem. The first of

these (stanzas 1-4), considerably the shortest of the three, establishes not

only the basic mood, but the elements - the spring, with its lilacs blooming in

the dooryard, the sinking star in the western sky, the song of the hermit

thrush in the deep woods - associated in the poet's mind with the American

countryside at the time of Lincoln's assassination and burial . . . (In) the

second section (stanzas 5-13) . . . the poet recounts the passage of Lincoln's

funeral train, his burial, and the land which he left behind . . . In the last section (stanzas 14-16) the poet

once more recalls the countryside, the life of the people in their daily

occupations, and the shock which Lincoln's death brought to them. The extended

contralto solo interpreting the message of the bird in the wood reflects on

death itself.

The movement of the poem, from an initial

recollection to the interpretation of the "message of the bird in the

wood," is suggested in microcosm in the first four stanzas.

The seasonal blooming of the lilac bush, the symbol of life and renewal,

triggers a reminiscence that recalls a specific time in the past and initiates

the poem's process. The reminiscence stirs feelings of grief. The focus of the poet's mourning is provided

at the end of the first stanza with, "thought of him I love." The revelation spawns the next stanza, an

intensification of the emotional trajectory of the opening stanza. The

exclamations of stanza two reveal the poet paralyzed by his grief for Lincoln,

the "powerful western fallen star."

The "harsh surrounding cloud that will not free (his)

soul" holds the poet

"powerless" to create: he is mute.

In stanza three the

poet turns from this impasse to contemplate the lilac bush in the present. The

exacting description of the living plant produces an adulatory upwelling that

parallels the immersion in grief of the first two stanzas. The praise is

terminated when the poet unexpectedly breaks a sprig from the lilac bush. The violent action disrupts the progress of

the poem. The poet's attention shifts from the lilac, with its power to urge

emotion, to the dimming sky and a bird song emanating from the forest. And in

doing so,

The complete pattern of the poem is

established with the advent of the bird in the fourth section. For here, in the

song of the thrush, the lilac and star are united (the bird sings "death's

outlet song of life"), and the potentiality of the poet's

"thought" is intimated. The song of the bird and the thought of the

poet, which also unites life and death, both lay claim to the third place in

the "trinity" brought by

spring; they are, as it were, the actuality and the possibility of poetic

utterance, which reconciles opposite appearances.

The goal of the poem is the "poetic

utterance." In stanza four however, only the exposition of conflicting

elements is complete. The transformation suggested by the bird song

materializes ten stanzas later near the completion of the poem.

With these issues in

mind, the "Introduction" to Roger Sessions' cantata When Lilacs

Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd is examined as a setting of the first four stanzas

of Whitman's poem. The stanza defines the basic musical formal unit, and each

stanza is further qualified in terms of its musical function and effect by the

instrumental interludes that surround it. The "Introduction" divides

into two sections (mm. 1-39, 40-80). The first section subdivides into two

periods. In the first period (mm. 1-22), stanza one is set for soprano and

baritone. In the second period, stanza two is set for chorus and includes the

instrumental interlude (mm. 23-39). The second section also subdivides into two

periods. Stanza three is set for baritone (mm. 39-50) and includes the

orchestral response (mm. 50-61). The concluding period (stanza four) is set for

soprano (mm. 61-77), and includes a brief coda (mm. 78-80).

The

opening movement functions as an exposition that establishes the harmonic and melodic

material of the cantata. A distinct tension is generated and maintained over

the course of the movement by presenting upbeat (anacrusic) phrases that are

generally met with a degree of truncation. The material is either molded to

reflect the degree of expansion particular to each stanza, or to serve a larger

formal effect. The truncated formal units are defined by cadences that are, in

their own right, generally undermined. As the movement progresses through its

varied moods, the continually truncated phrases and evaded cadences, and the

practice of substituting a new texture for a possible confirmation, produce an

inventory of unrealized expectations.

These manipulations are subtle. The movement is not perceived as halting

or developmentally deficient. And the integrity of the overall formal design is

not compromised by workings on the level of the phrase.

These phrase

procedures establish what constitutes musical continuity for the

“Introduction.” The effect of the climax,” and from this bush, a sprig, with

its flower, I break,” is achieved by engineering the contradiction of the

prevailing musical continuity. The musical flow is “broken” by the largest

truncation of the movement. The disruption of the musical line provides a

transition to a texture which is unprecedented in the previous music: a

recitative. With the musical line destroyed at the “break,” the bird music is

perceived as a puzzling addendum - harmonically and formally - suspended

between the inner world of the lilacs and the public statements of the second

movement. The recitative places the text of stanza four in high relief and

suggests its larger significance in the dramatic design of the cantata.

Sessions uses a formal unit traditionally associated with anacrusis to conclude

the “Introduction.” In this way both the poetic and musical ends are served.

The new texture conveys an intimacy, a single hermit thrush sings “in secluded

recesses¼death’s outlet

song of life.” Musically, the vocal arch and sparse orchestration provide a

brief repose at the end of the movement, however, because the recitative

supplies new material and a new texture, it does not satisfactorily address

closure for previous sections. It is possible to hear the final cadence of the

“Introduction” as a primarily local event, and best understood as providing

closure for the recitative. The return of the lilac motive in the coda can be

heard as a quiet musical reminiscence or, as a reminder that the energy

generated in each previous section was left unresolved at every cadence. The

recitative is yet another way of attenuating the degree of closure for a formal

unit. The final cadence of the movement is “deferred” and the role of the “Introduction”

as an anacrusis to the second movement is preserved and intensified.

Derivation of Referential Harmonies

When Lilacs Last in

the Dooryard Bloom'd is a twelve-tone composition based on the

following set (see Example 1).

Example 1: Twelve-tone Row,

Prime Form

In the "Introduction" Sessions

emphasizes the hexachord as the harmonic unit, and stresses pitch-class content

over rigorous use of the ordered set. Characteristically, Sessions uses the

twelve-tone system freely and Lilacs is no exception. The theory and

practices of the twelve-tone technique inform

this analysis, but the hexachordal basis of the music suggests avenues

of analytical thought other than the traditional note-count which, with

Sessions, cannot always be done thoroughly and with precision.

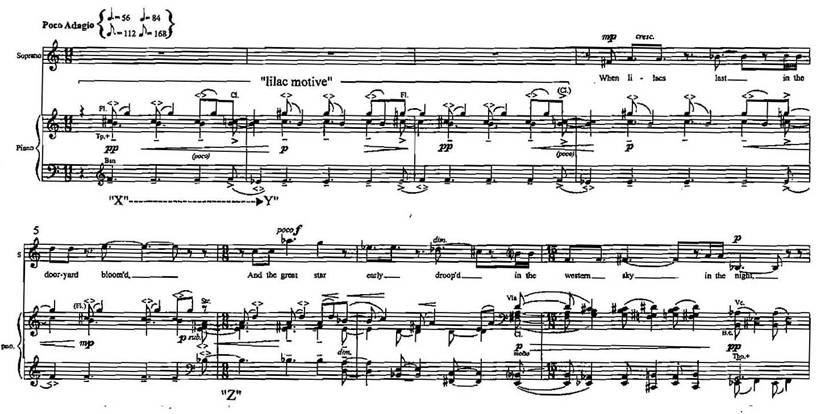

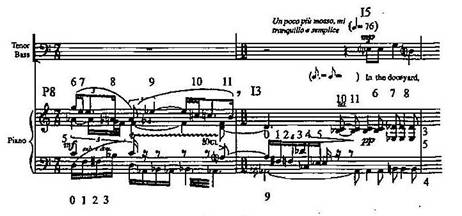

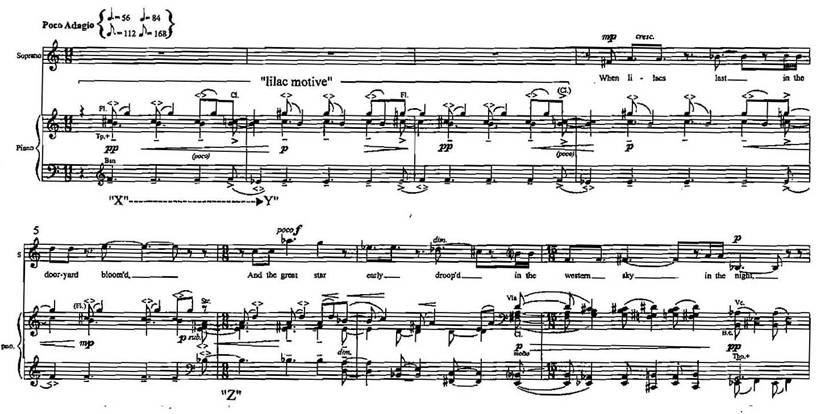

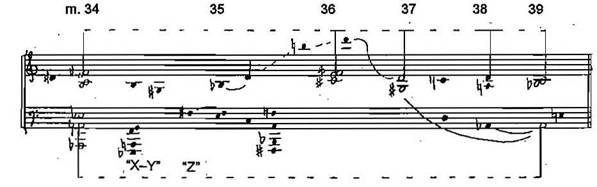

Example 2: When Lilacs Last in

the Dooryard Bloom’d mm. 1 - 8

© 1974 Merion Music,

Inc. Used By Permission

Example 2a: Semi-combinatorial

Partitioning, mm.1-8

The

opening measures are based on a partition of P0 and its

semi-combinatorial complement, I5 (see Examples 2 and 2a). The

repeated two-measure unit is constructed from seven pitch-classes with B

retained as a common tone. In the following discussion, I refer to the harmony

of m.1 as "X" and the harmony of m.2 as "Y" “(Y” is a

neighbor note elaboration of “X.” Later in the phrase the two become less

distinct and it becomes possible to refer to the “X–Y” complex"). The

soprano entrance completes the aggregate. The pitch collection of the soprano

part and the string chord of m.5 (verticalization of soprano part) are designated

as the "Z" harmony (see Example 3).

Example 3:

Referential

Harmonies Derived from mm. 1-5

The hexachords

of the set can be re-ordered to demonstrate an affinity with a corresponding

whole-tone collection. Because of the emphasis that the hexachord receives as

the beginning of the movement, and due to the way in which the hexachords will

be seen to be employed contextually in the "Introduction," I designate the whole-tone collections as

follows (see Example 4).

.

Example 4: Hexachords

Re-Ordered to Show Whole-Tone Affinities

The symmetrical

whole-tone sound is an unmistakable reference amid the dense chromaticism of

other passages. The implied stability of the symmetrical collection is,

however, consistently undermined by its formal placement at phrase beginnings.

The

referential hexachords (“X–Y” and “Z”) present the metaphorical content of the

poem. The material of the opening measures (i.e. the lilac motive

consisting of the tritone, C#-G, in “X” answered by B-G# in “Y” see

specifically Example 2, and generally, any intervals or chords set in the

characteristic iambic rhythmic pattern) is associated with the poetic

symbol of the lilacs throughout the cantata. In the "Introduction,"

the frequent use of the motive also suggests Spring, the season that supports

the renewal of all life and, for the poet, evokes memory. The “Z” harmony is

associated with death; the star obscured by darkness and the cloud. The

semi-combinatorial derivation strongly suggests this reading. The P0

soprano ascent of the first subphrase (renewal, life, blooming lilac) is

balanced by the descent of the inversional form, I5, in the second

subphrase ("great star early drooped in the western sky in the

night"). The concluding subphrase, in which "I" occurs for the

first time, supplies the subject of the sentence and the third element of the

"trinity," “the poet.”

The

use of the chamber ensemble (flute I, clarinet I, bassoons I, II, and muted

trumpets I, II), makes the opening period a personal statement in contrast to

the full orchestra of the chorus entrance. Sessions clearly wants the opening

attack to be heard in an upbeat context. The chamber group and subdued dynamics

minimize a "downbeat" accent on beat three, m.1. The ensuing pattern

of repetition (three statements of the “X” figure answered by three statements

of the “Y” figure, brought out instrumentally by the alternation of flute and clarinet)

propose a metric unit. The exact length, obscured by the rests on beats one and

two of m.1 one is clarified by the entrance of bassoon II that places a clear

metric accent on the downbeat of m. 2. As might be expected in a neighbor-note

elaboration, in which bar two is a neighbor chord (Y) to bar one (X), the

stress would be strong-weak. Here though, the metric accent is at variance with

the harmonic accent. The soprano entrance on m. 4, beat two, coincides

rhythmically with the lilac motive and the entrance on the weak “Y” harmony is

decidedly anacrusic.

The

soprano creates a harmonic opposition to the lilac motive by introducing the

five remaining pitch classes. Both the accompaniment and the soprano part

arrive at a rhetorically poignant and tense moment at the apex of the soprano

line. The soprano completes the adverbial clause and the aggregate on

"bloom'd" (e"), as the accompaniment places "strong"

metric weight on “X” harmony of the beginning accent. The clause demands

textual continuation and the anacrusic accompaniment, intensified by the added

pitch material of the soprano, demands a musical response. The expected

harmonic continuation, “Y,” which has normally occurred as an anticipation

(beat 11) in the previous groups, is replaced with “Z”: the pitch collection of

the soprano entrance presented as a simultaneity (with e" and bb" transferred

down an octave), a sonority that weights WT–B and in registral distribution,

the 014 trichord. The “X” harmony of the

lilac motive is thus answered with pitch material which, introduced by the

soprano in opposition, is transferred to another register to confirm motion

away from the static “X–Y” complex.

The harmonic accent

in m. 5 the winds to the muted strings (excluding contrabasses). The accent is

intensified by the dynamic contrast (subito piano) which is a subversion

of the pattern established to articulate the musical "adverbial

clause" (“When lilacs last...”). In the lilac motive, dynamics gradually

increase in mm. 3 and 4 to place weight on beat three of mm. 4 and 5

respectively. The pattern imparts a slight dynamic accent to the harmony change

from “X” to “Y” and the overall dynamic shape for the "adverbial

clause" is a crescendo from the pianissimo of the opening to the mezzo

piano of the vocal entrance, with the flute and voice reaching mezzo

forte at the high point of tension in both parts in m. 5. The dynamic contrast

of the strings separates their entrance from the lilac motive and vocal

entrance. The pitch material of the soprano is retained but presented in a

different register in a different timbral guise. These things prevent any

linear connection to the lilac motive. The “Z” harmony is not meant to be heard

as a neighbor to the previous “X–Y” statements. In response to the adverbial

clause that demands continuation, the register transfer and accompanying

changes produce the sensation of harmonic motion away from the lilac motive:

“X–Y” to “Z.” The octave transfer is the most striking aspect of the string

entrance and in defining “Z” as harmonic motion, the anticipation to m. 6 is

jarring.

The

event establishes two things that are essential in the syntax of the movement

and, more specifically, in extending Po and I5 in the harmonic

design of section one. First, the introduction of the soprano pitch material

and subsequent octave transfer as a simultaneity in the entrance of the strings

establishes the octave transfer of a pitch-class (or simultaneity) as a means

of generating harmonic motion.

The ear follows the octave transfer and the appearances of a single pitch-class

(or simultaneity) in different octaves as participants in different polyphonic

strands. The b flat" and e" of the soprano entrance transferred down

an octave in the string entrance are then part of different polyphonic strands.

Conversely, the displacement of a pitch-class in a specific register by local

voice-leading implies a change of octave for the pitch-class.

Secondly,

a contextual relationship is established for the harmonic material of the

opening measures, “X–Y” and “Z”, where ‘”X–Y” (WT–A) is associated with a phrase beginning and suggests a degree

of stability, and “Z” (WT–B) represents a harmonic opposition. As the formal

design of the first section evolves, the established context and function of

these harmonic entities is continually reinterpreted. For example, a degree of

harmonic motion is secured by transforming the “Z” harmony from its opposition

to “X–Y” (m. 5), into the role of a phrase-initial harmony (m. 22). In this way

in the first section, a tight network based on P0 and I5

results and this produces a "tonal" reference area for the rest of

the movement and ultimately, for the cantata.

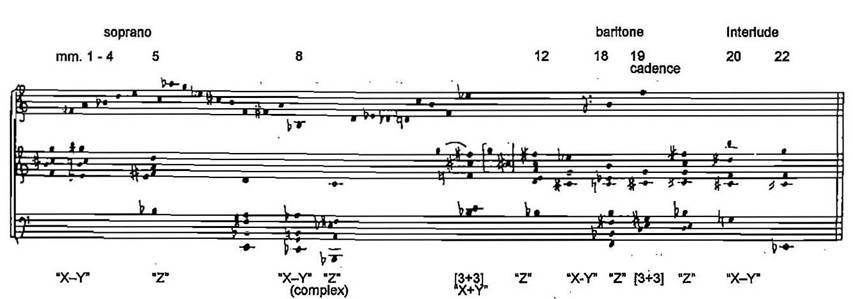

P0

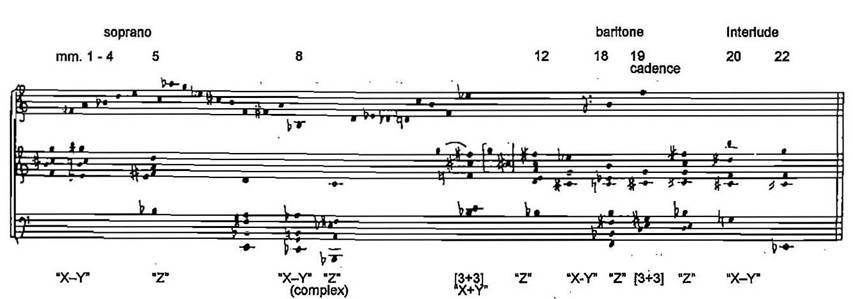

Harmonies Extended through Period One:

Measures 1-22

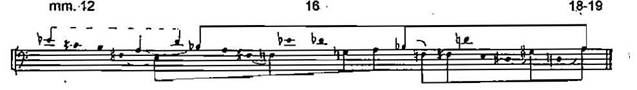

The

reduction of Example 5 shows how Po and I5 harmonies anchor the

first period. The second soprano subphrase (mm. 6-8) is supported by an

arpeggiation of the “Z” harmony. The subphrase arrival on "night" (m.

8, beat 10) is supported by a fusion of the “X–Y” harmony (“X–Y” heard now as a

single event). The concluding subphrase (mm. 9-11) begins with support from “Z”

in m. 9 and concludes with an undermined cadence on the downbeat of m. 11. The

accompaniment extends the phrase beyond the soprano cadence to overlap with the

baritone entrance in m. 12 (see Example 6).

In

the approach to the soprano arrival in m. 8, the “Z” harmony marks its lowest registral

appearance on m. 7, beat nine. As in the analogous place in the previous

measure, the whole chord is treated as an anticipation which is tied through

beat one of m. 8 and delays the move to “X–Y”.” The “X–Y” “complex is

ornamented by an upper neighbor harmony that receives durational emphasis.

Through the voice exchange, G-A flat, and the subsequent reduction in harmonic

rhythm, the “X–Y” “harmony is positioned to support the articulation of the

soprano subphrase ending on B flat ("night").

Example 5: P0 and I5 Harmonies,

mm. 1 - 22

Example 6:

When

Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d mm. 6 - 12

© 1974 Merion Music,

Inc. Used By Permission

The

previous association of B flat with the “Z” harmony is recalled in the final

tetrachord of the soprano part, F-F#-A-B flat, and the pitch gains new emphasis

from its isolation by skip. The arrival on B flat strengthens the stability of

the pitch originally introduced as the "bass" of the harmony of m. 6,

yet by supporting the B flat with a harmonic change (“X–Y”) in a new register,

the stability of the arrival is undercut. The melodic skip produces the

sensation that the soprano went too far, perhaps moving into something other

than a cadential register appropriate to the subphrase.

The accompaniment

confirms the weakness of this arrival by extending the subphrase to the overlap

on the downbeat of m. 9. The beginning of the subphrase receives a slight

metric accent from the low register placement of the “Z” harmony, but this

emphasis is partially neutralized because of the return of the “Z”

harmony. The harmonic motion of the phrase summarized in Example 5 shows that

the “Z” harmony, initially responsible for the motion away from “X–Y”,”

actually surrounds the subphrase articulation on “X–Y” (m. 8). The “Z” harmony

has replaced “X–Y” as the controlling harmony of the phrase.

The

avoidance of harmonic contrast in the opening of the subphrase is offset by the

thematic accent supplied by the bassoon entrance. The bassoon states a

transposition of the tritone lilac motive, F#-C, that confirms the harmonic

shift to “Z.” After its exclusion from the accompaniment descent (which depicts

death/star, and not life/lilac), the return of the tritone makes the beginning of

the third subphrase in m. 9 parallel to that of the opening subphrase.

The expected motivic

continuation (i.e. to the second half of the pairing associated with the

original statement of the lilac motive in mm. 1-2, ie., “X” to “Y,” or in this

case, F#-C balanced by F-C#) is denied by the soprano entrance which recalls

the upbeat quality of the opening subphrase. The direction of the line is

momentarily unclear. The durational emphasis in the soprano part on "I

mourn, and yet shall mourn" is opposite from that of the lilac motive in

the accompaniment. Life and death are set against one another. The rhythmic

stalemate is broken by the contrabasses and cellos that undermined the arrival

in m. 8. Here they continue to a sforzando accent in m. 10 which, in

combination with the entrance of the lilac motive in the first violins,

provides an accent that evokes the melodic ascent to "ever returning

spring" in the soprano part. The soprano's stepwise "mourning"

is immediately contrasted by the melodic leap to "spring." The

subphrase concludes with an affirmation in the text that is echoed musically by

the cadence on the downbeat of m. 11.

The

cadence completes a circular formal design. The F-B-E flat of the soprano line

and the C#-G emphasis in the accompaniment recall the “X–Y” harmony of the

opening. Yet, the stability of the soprano arrival is undermined by a

harmonization that is not explicitly from either of the referential hexachords

(P0A or P0B). The harmony consists of a combination of

two whole-tone trichords: B flat-C-F# and C#-D#-F. The WT–B trichord is

introduced as an anticipation and held over the barline, while the soprano's E

flat" is part of the WT–A trichord that is placed against WT–B on the

downbeat. The active, non-referential harmony receives the accent of metric

weight and, in combination with the emerging instrumental interlude, provides

movement to the new phrase beginning with the baritone entrance (m. 12, beat 7)

(see Example 7).

Example 7:

Interlude, mm. 11-12

The

instrumental interlude executes the octave transfer of the “X–Y” harmony to support

the baritone entrance. The first violins state the opening lilac motive in

register (m. 10, C#-G), and transform the previously static repeating lilac

figure into a melodic entity which exceeds the registral boundary established in the opening measures.

The oboe and clarinet I retain the C#-G dyad beneath the violin melody through

m. 11. One perceives linear and harmonic motion away from the oblique “X–Y”

reference when the C#-G dyad is replaced by C-F# dyad as part of the “Z”

harmony on the downbeat of m. 12. The violin descent through F# anticipates the

definitive move to C-F# (supported by Z) completed by the oboe I and flute I. The

“Z” harmony provides a foil between the two “X–Y” expressions. The “X–Y”

harmony (heard as a single event) is now associated with "ever-returning

spring" in a new register and context. It supplies a head-accented phrase

initiation.

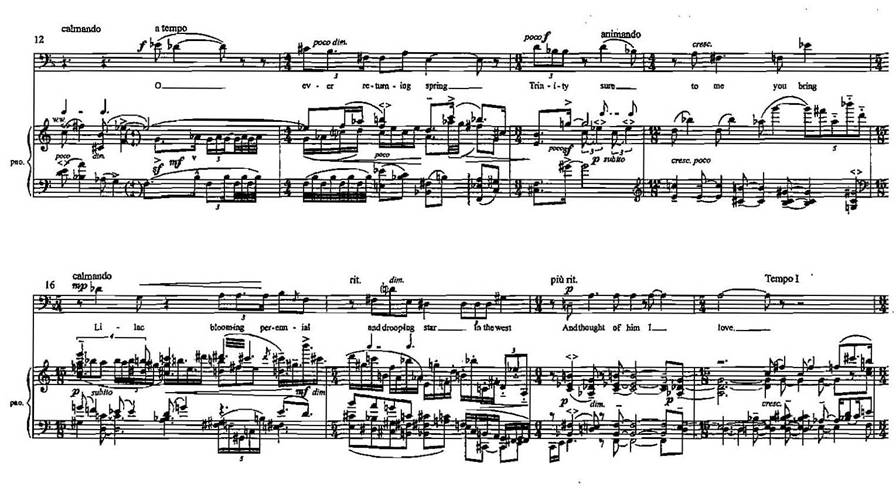

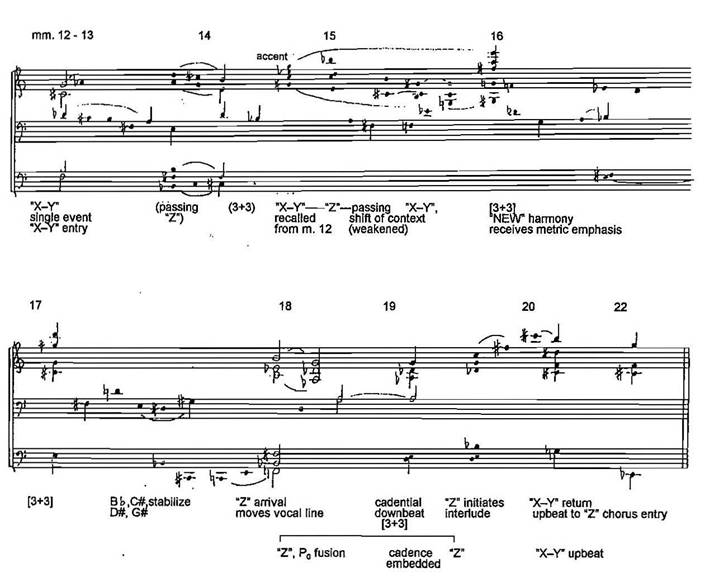

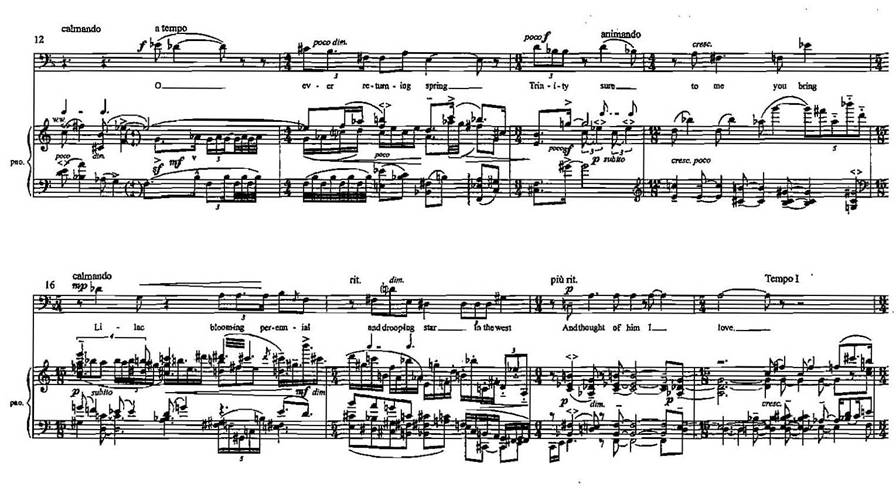

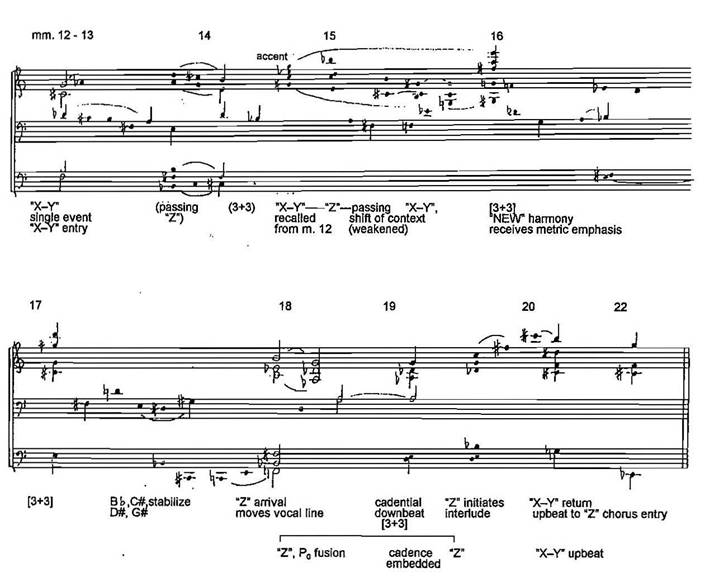

The

baritone phrase divides into two subphrases, mm. 12-15 and mm. 16-19 (see

Example 8). The stanza is set so that the greatest textual emphasis aligns with

the goal of the musical period. The "lilacs" of the opening are

finally connected to "thought of him I love" at the baritone cadence

on the downbeat of m. 19. If the soprano and baritone are perceived to be in

this relationship, a convincing cadence for the period depends on creating a

perceptible linear connection between the two phrases, one that integrates

previously established reference points into a renewed drive to cadence. The

strategy is immediately suggested by the beginning of the “X–Y” phrase which

links the baritone with the opening measures, and shows a deep affinity with

"ever-returning spring" as the source of poetic and musical

impetus.

An

explicit connection is made when the eb" of

the soprano cadence on "spring" is "passed" via octave

transfer to begin the baritone phrase on Eb' (the Eb' is an

appoggiatura to the D flat ', and the trumpet picks up the E flat " and

retains it as the chord tone). The baritone subphrase begins in the register

left and isolated by skip in the soprano part (m. 10, "I mourn, and yet

shall mourn") and descends into the register that plays a role in forming

the cadence. The tritone, E flat -A (mm.

12-13) in the baritone exclamation moves to D-Bb in m. 14 (the D also receives lower neighbor inflection

from the C#, D flat). The B flat, although supported by a non-referential

harmony and functioning in a new formal context, recalls the soprano subphrase

end on "night." The baritone phrase reactivates the soprano B flat

and takes it to the cadential A in m. 19. The linear motion to A is supported

by harmonic motion in the phrase from the clear “X–Y” harmony of m. 12, to a

less obvious “Z” harmony in m. 18 (see Example 9).

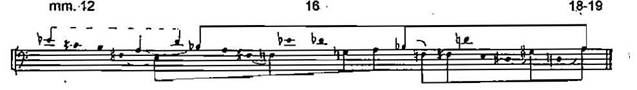

Example 8: Introduction,

mm. 12-19

© 1974

Merion Music, Inc. Used By Permission

Example

9:

Reduction of mm. 12 - 22

\

The

use of a non-referential harmony on the downbeat of m. 14 to support the B flat

begins to weaken the influence of “X–Y.” Despite the reiteration of D-Bb, any stability in

the line is further undermined by the mid-phrase harmonic accent (last

sixteenth of beat 1, m. 14). The accent is created by the shift in register,

vibraphone punctuation, and the sustained notes that contrast the intricate

accompaniment motion to the downbeat of m. 14. The harmony of the accent

preserves the g'-g#' neighbor-note pair introduced in the second violins (mm.

12-13). The g' of m. 12-13 is transferred back to the register identified with

the lilac motive (m. 1-2) and returns the pitch-class G to an active but as

yet, undefined role. The accent also serves to introduce a variation of the

lilac motive which extends through m. 15 and provides an upbeat to m. 16. The

registral shift of the accent in m. 14 focuses full attention on the vocal move

from B flat to A (supported by Z) in the subphrase continuation and supplies a

mid-phrase foreshadowing of the linear cadential goal.

The

eb' vocal return in the

vocal subphrase end in m. 15 recalls the beginning of the subphrase and creates

a circular progression. The subphrase end provides a breath in the baritone

phrase group and postpones the revelation of the meaning of the final stanza.

The eb'-d' in

subphrase one is echoed by the eb'-db' relationship that

extends across the formal division between subphrases one and two. The circular

melodic design is reflected in the harmonic structure. The E flat' subphrase

ending is supported a passing ”X–Y” harmony that weights the downbeat of m. 16.

“X–Y” is transformed into a midphrase upbeat to a non-referential chord that

recalls in structure (3+3) the phrase-extension harmony in m. 11. The return of

“X–Y” places the G-G# dyad in a lower register (horns) and employs it in a

voice exchange over the barline into m. 16 (G-G# to G#-G). Despite the

inclusion of the familiar dyad, the harmony of m. 16 is heard as

non-referential. The vocal entrance on the original lilac motive (Db–G, transposed down

an octave) enforces a powerful reference to "lilac" in the text, but

any reference to its previous context is obscured by the different

harmonization. The g natural isolated by skip in the lilac motive is the first

baritone G and, the intermediate goal of the low register of the compound line

established in mm. 13-15 [(E-F#, F-(G-A)]. As the harmony moves away from

“X–Y”, the cadential emphasis on A begins to take shape from this lower

neighbor, G, which represents the ultimate placement of the pitch-class in the

phrase (see Example 10).

Example 10: Baritone Line

Reduction, mm. 12-19

The

local destination of the ascending vocal line is the B flat incomplete neighbor

to A. The A-B flat, G#-A pairs are kept active in the accompaniment and

culminate in the alto flute anticipation of the baritone's cadential A (m. 17).

The high D in m. 17, which functions as an elaboration of the low register

line, also supplants both E flat and D flat (associated with the phrase

beginnings in m. 16). This facilitates the octave transfer of the D#, which is

obtained by exceeding the previous registral boundary E (m. 13), and initiates

a descent toward D. The vocal D# receives support from a B flat in the bass,

and, in turn, the D# provides support for a G# in the vocal line creating a

heavily emphasized fourth that will open out into the cadential fifth, D-A (m.

18). The cadence is further strengthened

by the reminiscence of the wedge-shaped linear motion of the opening motto, and

the chromatic inflection, G-G#-A which provides the definitive articulation.

Although the cadential pitches arrive in m. 18, the actual cadential moment

occurs on the downbeat of m. 19 (end of the vocal line) with the syncopations

in the accompaniment leading precisely there.

The

arrival in m. 18 completes the "trinity:" lilac, star, and

"thought of him I love." The third element is accentuated by the

abrupt cessation of the developed accompaniment texture. The contrabasses absorb

the full weight of the metric accent in m. 18 and set the F pedal in the bass. The

return of the low register (absent since m. 14) provides support (C#) for the

vocal G#. The bass figure echoes the vocal wedge when it expands to F and

forces the baritone's G# to A. The baritone A is supported by a fusion of P0

over the F pedal (see Example 11).

Example

11: P0 Fusion

Although

scrambled, the harmonies reflect pitch class pairings associated with P0, and,

considering the primacy of the baritone arrival, are weighted toward “Z” in the

first harmony (Bb-F#-A-C-D-E).

The P0 aggregate alternates between this representation of “Z” and

the variation of ”X–Y” in a syncopated figure based on the characteristic rhythm

of the lilac motive. The syncopated figure defers cadential emphasis to the

arrival on "love," which is the downbeat of the period, the moment of

rhythmic release. The cadence is weighted by the removal of the F pedal at the

anticipation of the cadential harmony D-E-G#/A-C#-G. The whole-tone trichord

structure of the harmony recalls the harmony of both m. 16 and m. 11

(associated with opposition and phrase continuation) and, its use in the

cadence is a change of context for that harmony. Although C#-G is retained in

the cadential harmony (representing ”X–Y”), the overall motion of the phrase to

the “Z” harmony in m. 18 is, at the last moment, deferred to a

"non-aligned" harmony.

The motion to the cadence, while essentially

dependent on harmonically supported linear events for its effect, also becomes

a search for clarity of harmonic reference. As successive phrases in the period

are lengthened, previously established harmonic reference points are therefore

separated by a larger span. And in this design, the beginnings and endings of

formal units (from subphrases to sections) acquire a larger articulative role

by either their employment or their avoidance of a referential harmony. A

variety of effects are achieved when the prevailing pattern of contextual

employment is violated by the substitution of a non-referential sonority at a

moment of formal import.

Example 12: When Lilacs Last in

the Dooryard Bloom’d mm. 18 - 22

© 1974 Merion Music,

Inc. Used By Permission

Though the cadence on

the downbeat of m. 19 is convincing, its role in the section (mm. 1-39) is

qualified by both its harmonic structure and the referential harmonies that surround

the articulation. While the baritone phrase consists of a move from “X–Y” (incipit,

m. 12) to “Z” (m. 18), the structure of the cadential harmony (m. 19) confirms

neither. It is poised between “X–Y” and “Z” (3 pitch classes. “X–Y”, WT–A and 3

pitch classes “ Z,” WT–B). The cadential harmony is a critical substitution

that recalls the unstable harmony used in the articulation of the downbeat of

m. 11 which in that context, forced the phrase onwards. Here the association

challenges (but does not offset) the high degree of emphasis conferred by the

cadential downbeat and its "accent of weight."

The surrounding

referential harmonies reveal that the motion of the phrase from “X–Y” (m. 12)

to “Z” (m. 18) is confirmed after the cadence when “Z” replaces “X–Y” in

the transposed return of the original lilac motive (m. 19, see Example 12). At this

point, however, the “Z” harmony is part of a formal unit that moves away from

the cadence. It provides an upbeat to the “X–Y” harmony of m. 20 which is

extended through m. 21 and becomes, at the end of the interlude, an upbeat

itself. The change in function of the “X–Y” complex over the course of the

phrase and period represents a process of harmonic reinterpretation which is

completed by the clear entrance of the “Z” phrase in the chorus. By avoiding

clarity of harmonic reference at the cadence (the moment of formal and textual

emphasis), the structural goal of the network of referential chords is deferred

and effectively placed at the beginning of the next period which in turn, as a

beginning, offers no stability.

The opening period

defines a model for cadence formation in the movement. The three remaining

cadential articulations will be examined within this frame of reference: the

cadence on the downbeat of m. 34 that concludes the chorus period and Section

One, the arrival on the downbeat of m. 50 that articulates "I break"

and the final cadence of the movement on the downbeat of m. 77. By means that

vary in each case, the compositional strategy is to defer emphasis from

cadential repose to the preparation for the onset of the next formal section.

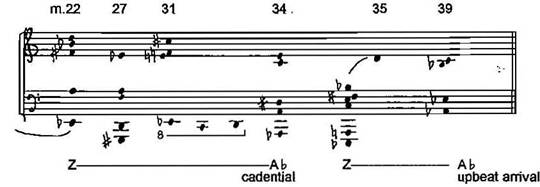

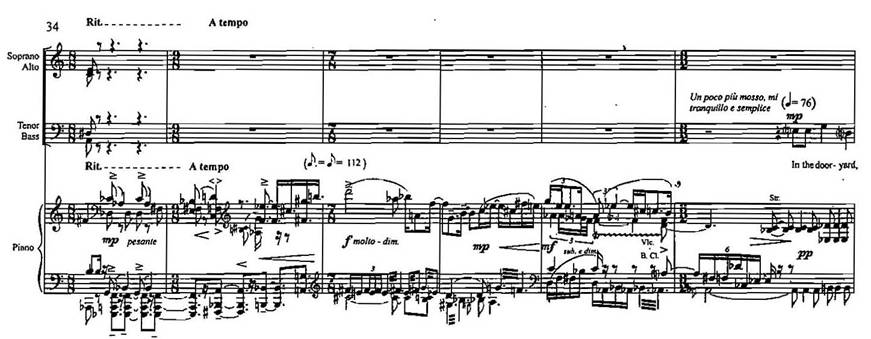

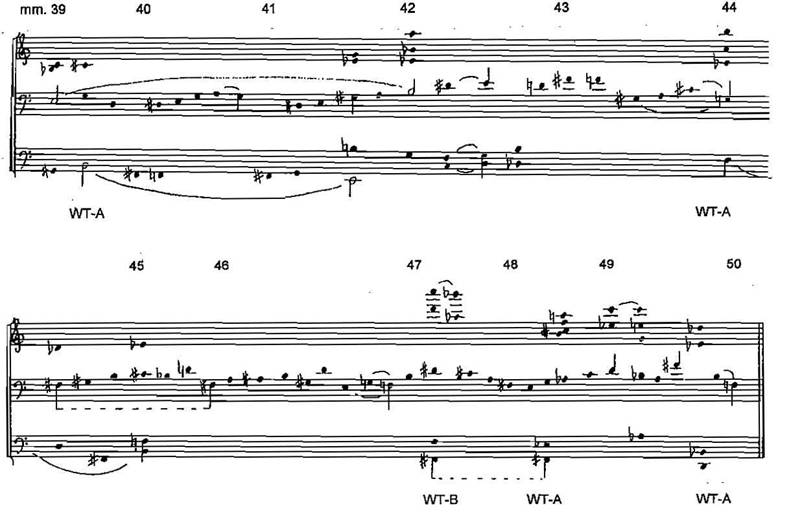

Cadence Formation for Section One: Measures 22-39

While the text of mm.

18-19 contains a revelation of deep resonance, it is the midpoint in the

intensification of emotion that concludes with the speaker's acknowledgement

that grief, "will not free (his) soul" (m. 34). In stanza two, abject

grief is conveyed by a series of assertions. "The exclamatory mode of

grief . . . reveals its point in its syntax. There are no verbs, hence there

can be no sentences, only clauses. Nothing can be done; there can be no shaping

into meaning; only cries of loss, grief, obscurity, helplessness."

The "shaping into meaning" implicitly denied by the syntax of the

stanza is given an interpretation by the musical setting. The exclamatory

fragments of text are directed toward cadence in part by the formal design of

the period. Declamatory opening and closing phrases for full chorus (mm. 22-23,

mm. 31-34) frame a texture of writing for individual voice parts (mm. 24-30,

see Example 13). In conjunction with the overall design, the music is directed

to the downbeat of m. 34 by the phrase behavior exhibited by each component.

The head-accented chorus entry is extended by the bass line by way of a

negative metric accent on the downbeat of m. 24 which evokes the series of

end-accented exclamations for the individual voice parts. These exclamations

pair with one another and create an internal balance that is offset by the

anacrusis in the accompaniment (m. 30). Springing from the downbeat of m. 31,

the concluding chorus statement reflects the intervening phrase behavior of the

individual voice parts and is now clearly tail-accented. In this way, the

phrase structure provides an inexorable push to a conclusion in a potentially

diffuse passage of the text.

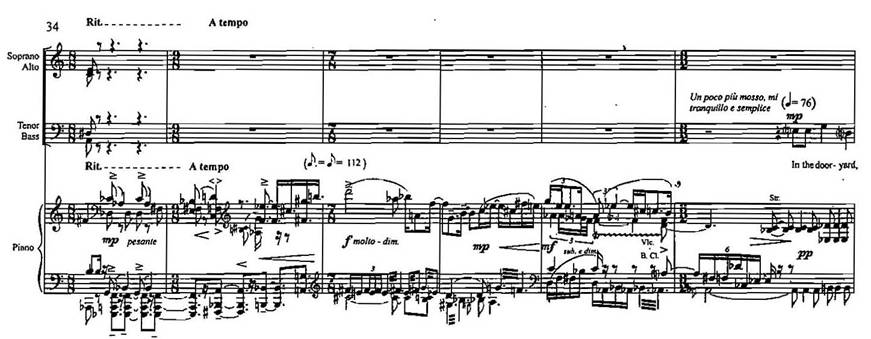

Example 13: When Lilacs Last in

the Dooryard Bloom’d mm. 22 - 34

© 1974 Merion Music Inc. Used By Permission

.

The chorus period

begins from a shared harmonic reference (the “Z” harmony and tetrachords of P0)

and proceeds to a cadence on a harmony outside the P0 referential

group. (m. 9) The harmonic motion away from P0 is confirmed in the

interlude when the “Z” harmony returns (m. 35) and moves to a variation (octave

transfer) of the m. 34 cadential harmony in m. 39. Therefore, the previous

cadential goal (m. 34) is re-interpreted in the modulatory interlude to become

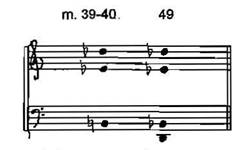

an anacrusis to the new harmonic area (I3) of section two (see Example 14.)

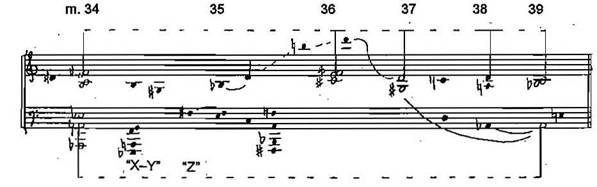

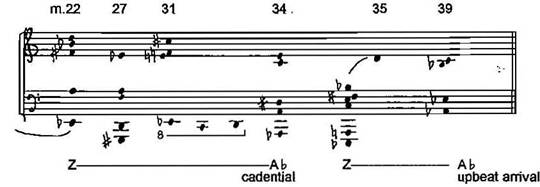

Example 14: Overall Graph of

Motion, mm. 22-34, 34-39

The

cadence of section one is placed within a framework of harmonic reference that has

as its goal the opening of section two. The strategy is a parallel expansion of

the model established in the treatment of the cadence in m. 19. Yet in this

case the demands are greater, since the cadence must close the section without

impeding the harmonic plan. To secure a cadence that is meaningful for the

section, the periods are fused by linear connections that operate across the

formal division (in m. 19). The cadential A (and its harmonic pairing with G#)

of m.19 and the low E flat of m. 22 are the source for the principal octave

transfers developed to articulate the cadence for the section on the downbeat

of m. 34 (see Example 15.)

Example

15: mm. 19-34

Beyond its

role as the anacrusis to the chorus entrance in m. 22, the interlude preserves

the cadential A natural and contrasts its “Z” association by placing it in an

“X–Y” harmonic context in which it provides a secondary rhythmic accent to the

violin line. In the chorus entrance the A natural returns as part of the “Z”

harmony. The final and most significant appearance of the A natural occurs on

the downbeat of m. 27 in an entirely new harmonization.

The stressed low F

natural (m. 18) reserved to call attention to the cadential articulation is

brought into a new focus when it moves to the E flat flat (m. 22, sforzando)

and functions as the primary rhythmic accent of the interlude. The linear bass

creates motion away from the cadence in m. 19 and, the E flat is retained

across the formal boundary (m. 22) to provide a literal connection between the

periods. Without the accent provided by a change in the bass, the declamation

of the interlude and chorus form a larger rhythmic unit. The energy of the

interlude and the chorus entrance is directed to the negative metric accent and

tempo change on the downbeat of m. 24. The phrase is extended to the downbeat

of m. 27 by activating the bass and exploiting the “Z” tetrachord in the

extreme low register (contrabassoon, F#-A-B flat-D).The octave transfer of the

A flat in this process to the anticipation in the bass (m. 26) converges with

the A arrival in the alto on the downbeat of m. 27. The harmonic arrival

represents a completion of the context change for the former cadential A into

an active tone paired with D#, and establishes a harmonic reference critical to

forging the cadence in m. 34.

The

real force behind the cadence in m. 34 is not the similarity of pitch content

between m. 27 and m. 34, but rather the reinterpretation of this chord within

the phrase structure; occurring first as a mid-phrase overlap in m. 27, it becomes

the metric goal of the period in m. 34. In its first guise, the harmony of m.

27 supplies a harmonic accent that works contrapuntally against the formal

design. The arrival in the alto on the hard-won and sustained A natural occurs

within the phrasal process, and provides a metric accent to introduce the

soprano-baritone phrase pair.

The

return of the declamation (m. 31) is supported by the E flat transferred down

an octave from its original register in m. 22. It is foreshadowed by linear

motion in that register. The D in m. 27-28 moves in the contrabassoon (not

shown in piano-vocal score). In m. 29-30 the contrabassoon and contrabasses

move to F which is inflected by its chromatic lower neighbor, E natural. The F

natural is left isolated by skip (beat 8, m. 30) in the anacrusis to m. 31. The F-E flat

connection over the barline recalls, in octave transposition, the bass motion

of the interlude and first declamation and participates in a double neighbor

(D-F-E flat) motion. The return of the E flat delineates the change of harmony;

the same group of pitch-classes associated with motion at the beginning of the

section are re-instituted by octave transfer. When the declamation begins with

a new harmony, the E flat of m. 31 is dissociated from the “Z” of m. 22. The

motion of E flat in m. 31 to A flat in m. 34 is parallel to that of the opening

declamation, but the progression is now compressed and intensifies the motion

to cadence.

The

octave transfers of A-D# and G# are used in support of the strong linear motion that occurs toward the

cadential goal, E natural (contralto part). The pitch is weighted by the

double-neighbor motion (D#-F-E). The E flat, associated with the entry in the

bass (m. 22), is active in both registers inflecting E natural in the

contralto, and providing harmonic support to the cadential A flat in the bass

(The E flat of m. 31 is transferred from the bass to the contralto in m. 31,

while in m. 32, the soprano emphasizes F natural). The harmonic structure of

the sectional cadence reflects the cadence of m. 19. The 3+3 configuration is represented as 2+2

in the chorus and on the whole, the sectional cadence is weighted toward WT–B

and confirms the harmonic motion begun with the “Z” entry of the chorus.

The closing choral

declamation reveals that the poet is trapped by memory. For the poem to

continue beyond the emotional impasse, a psychological shift must occur that

will alter the poet's frame of reference and allow the formulation of a

response. The process is suggested musically when, immediately following the

cadence that closes off the exclamations, the lilac motive is quoted (m. 34).

Before the cadence can be confirmed, the most vivid motive of the movement is

seemingly “forced in” to ensure a connection across the cadence and to

supply associations which oppose challenge the predominance of the arrival.

The appearance of the lilac motive within the

cadential ritardando creates momentary confusion since the lilac quote

may also be viewed as recalling the cadential texture of mm. 18-19.

Despite this association, the thematic accent is supported in ways that mark it

as a beginning. Strong linear motion around (and away from) the cadence results

when the stressed low D of the chorus period (isolated by skip in m. 33) is

displaced by the E flat (m. 34). The semi-tone motion in the bass echoes the

D#-E of the cadence. The low E flat (transferred to the bass from the tenor)

now resonates as part of the WT-A collection and provides harmonic contrast

that sets the motive off from the cadence. The sense of harmonic change is

intensified by contrast with the fixed B natural retained from the cadence and

the lilac motive entrance is enhanced by the timbre change to woodwinds

(English Horn, bass clarinet, and bassoons) that evokes its earlier appearances

(see Example 16).The intervallic alteration of the motivic reference (the

descending minor third substitutes for the ascending tritone) produces an

immediate and powerful effect. With the tritone excluded from the opening of

the phrase, the familiar theme is disarmed and cut off from its earlier

association with the upbeat lilac motive. The alteration is confirmed with the

return of “Z” on the downbeat of m. 35. The a tempo and melodic turn

highlight the harmonic shift, but the harmony once associated with a strident

entry (m. 22) now provides the impetus for a lyrical interlude.

Example 16: Interlude, mm 34-39

The interlude offers a

direct contrast in character and changes the function of the A flat harmony

from the cadential goal (m. 34) to an anacrusis (m. 39). The first step occurs

in m. 34 as the D#-A transfer in the bass supersedes the cadential A flat as

part of the WT-A harmony used for thematic support. The subsequent octave

transfer and return of the A flat in m. 39 as an unstable harmonic tone is

prepared by a linear descent from the cadential E octave transfer (reversing

the D#-E motion of the cadence in the interlude to E-D-C). The delay of the arrival

on the passing tone d' until m. 38 by

the employment of D natural in an octave transfer becomes the basis for the

lyrical interlude (see Example 17).

Example 17: Reduction of

Interlude with D Octave Transfer (D#-E, E-D-C)

The D of the familiar

“Z” harmony (transferred in m. 35 from the choral bass) is transferred two

octaves to receive a durational and expressive accent on the downbeat of m. 36.

The melodic accent on D is supported by a change of harmony that recalls but

destabilizes elements of the cadence in m. 34 (E-F#-C becomes E-F#-C#). Further

emphasis on the downbeat of m. 36 is conferred by the interruption of activity

in the bass. One is aware that the transfer of d" to d' is completed and

that the E has been displaced when the lyrical line drops out at the end of m.

38. The exposed pairing of D with the A flat is distinct from the harmony of m.

34, “Z” of m 35, and the harmony of m. 36. The octave transfer of the A flat enters

as an anticipation in m. 38 and obscures the meter. A negative accent on the

downbeat of m. 39 occurs when the clarinet drops out and the unstable d',

treated as an appoggiatura to C (the C completes the octave transfer of the

cadential harmony of m. 34 which is now unstable), enhances the upbeat,

preparatory function of the interlude.

A clear hexachordal

orientation emerges at this formal juncture to intensify the local effect and

articulate the culmination of the large-scale harmonic motion. The arrival of A

flat which represents a variation of the harmony of m. 34 is, in the larger

scheme, contained in I3B. This reflects a change of context for the

WT-A collection (from the entry in m. 22 to the upbeat) and makes the

modulation to the harmonic area of section two unmistakable (see Example 18).

Example 18: When Lilacs Last in

the Dooryard Bloom’d mm. 38 - 39, Note Count

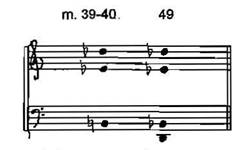

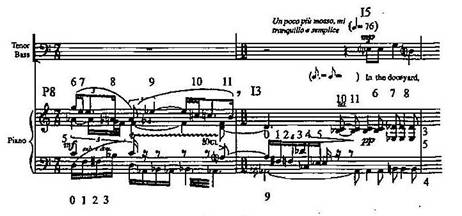

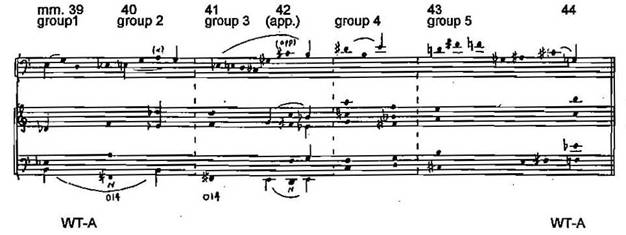

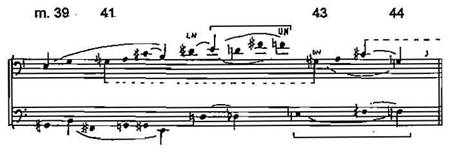

Section Two, Period One: Measures 39-60

The physical characteristics

of the lilac bush inspire stanza three: "In contrast the verse for the

lilac swells out, the growing thing stands, and the present participles

proclaim its continuous and active life."

The stanza is constructed as a chain of participial phrases that are directed

in one long breath to the concluding predicate, "(I) break." The

external action is a startling turn in the poem that is echoed by a

simultaneous musical surprise. The predicate is set so that it receives an

unexpectedly strong metric accent which goes beyond depicting the local event.

It functions then, as the musical accent of the movement, and severs the

carefully extended musical line.

The

problem in achieving this compositional effect is that if one hears the period

as an upbeat leading precisely to the metric accent, then there is no disjunct

event. It simply reflects previous phrase procedures and represents motion to

another avoided arrival. To bypass this association, a distinction must be made

in the character of the material and in the way phrases are generated. Here the

growing plant calls forth a vocal line that also grows, capable of responding

in varying degrees to the images of sight and smell evoked in the text. As the

period unfolds, the phrase procedure creates its own expectations for

continuation and cadence and it is this contrasting development which is then

abruptly terminated.

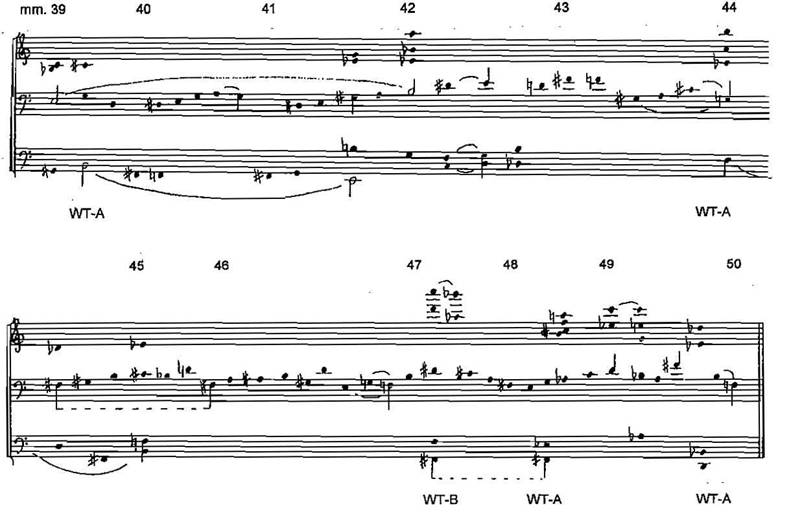

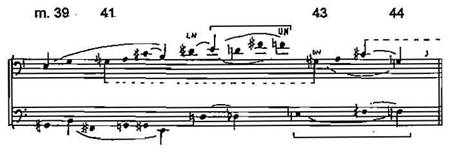

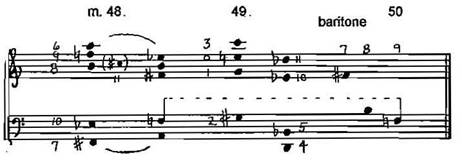

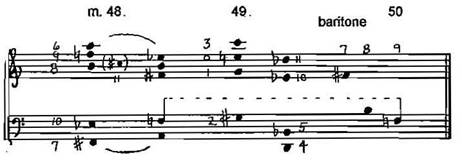

Example

19a: When

Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d mm. 39 - 50

© 1974 Merion Music

Inc. Used By Permission

Example

19b: Reduction

of Baritone Period, mm. 39 - 50

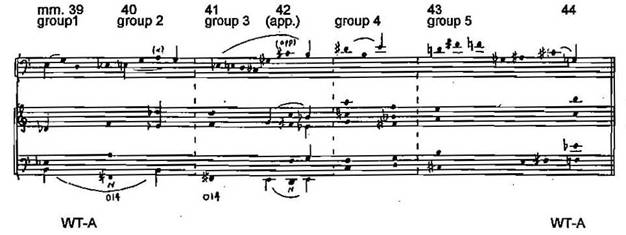

The

baritone period consists of one phrase (mm. 40-50, anacrusis in m. 39) that

divides into two subphrases (mm. 40-44, 45-50) and further subdivides into five

groups per subphrase

(see Example 19a and b). With the modulation from P0 to I3

confirmed, the movement has earned a degree of repose. The relative stability

of the harmonic area is reinforced and extended by the clear trichordal basis

of the accompaniment that is set as an augmentation of the lilac rhythm. The

new harmonic area is the point of reference against which the setting of the

“breaking sprig” will be measured. In the following example, the trichordal

harmony supports the group as the principle unit of melodic construction (see

Example 20).

Example

20:

Melodic/Harmonic Groups

The

first two melodic groups are paired together and supported by the harmony that

returns to close off in m. 40. The second group begins with a variation on the

014 trichord in the accompaniment (F#-A-F becomes F#-F-D) that was employed as

a neighbor harmony in groups one and two.

Instead of closing off with the voice group that ends on the downbeat of

m. 42 (with the return of 014, D-F-F#), the accompaniment treats the 014 as an

accented neighbor harmony between two expressions of an E-rooted harmony

(anacrusis to m. 42). The first three vocal groups generate a rising melody

that outlines the fifth E-B, and the E-rooted harmony in m. 42 supplies

harmonic support that confirms the relationship (see Example 21).

Example

21:

Stability of the Fifth

The

ascent of the line to the arrival on B, brought out by the dynamic swell and animando

in the anacrusis to m. 42, coincides with the expressive moment when the

subject of the participial phrase, “lilac bush” appears ("stands the lilac

bush"). These nuances, and the beginning of a more elaborate accompaniment

at this point, prevent a fully supported harmonic arrival on B (with E natural

in the bass) from stalling the phrase. The push through the articulation of the

B arrival also conceals the parallel relationship that exists between that

arrival and the group ending (B in the bass) in m. 40. The E-B is projected as

a referential stability without undercutting the motion of the phrase. The

stability of E in this context is clearly related to its history as the

cadential goal in m. 34, its reinterpretations in the interlude and in m. 39

(the octave transfer into the vocal entrance). By its pairing with B in the

subphrase, the resultant fifth supersedes any whole-tone affinity and asserts E

as a local tonal center.

The

arrival of the b natural in the vocal line begins a further development in the

upper register which is then left incomplete by the articulation of the

subphrase end. The pitches that signaled motion away from the g natural in m.

41 (g#-a) are reinterpreted in m. 43 to end the subphrase on that pitch (g

natural in m. 44). The registral connection and the WT-A harmonization of the

arrival make the subphrase into a larger group. (See Example 22.)

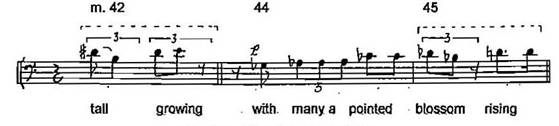

Example

22:

Subphrase 1

The use of

G to connect the goal with the beginning of the subphrase suggests a method of construction

that becomes more apparent on the level of the phrase. By utilizing interval groups, successive

events are related internally by the recurrence of similar motivic fragments,

or particular pitches. In the following example, a portion of the middle of the

first subphrase is employed at the beginning of the second subphrase (see

Example 23).

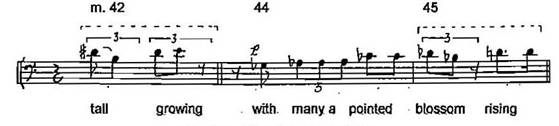

Example 23: Internal Repetition

The

motivic relationship heard across the subphrase articulation preserves consistency

in the tone-painting ("growing"-"rising") and obscures the

formal division by suggesting a continuation and developmental variation of the

material.

The

development of the second subphrase displays another aspect of the internal

register connection. (See Example 24.)

Example 24: Internal Registral

Connections in Second Subphrase

The baritone phrase closes off on the f

natural in m. 46. The f# from the anacrusis to m. 45 returns registrally

isolated ("delicate") in the middle of the phrase. In m. 46 it "splits" into e natural

and g for the double neighbor embellishment of f. By concluding the melodic

activity in that register, the beginning in m. 47, which coincides with the highpoint of emotion

in the text, is given maximum registral contrast. The phrase is designed so

that both the vocal line and the accompaniment use beat two of m. 47 as a point

of departure. In a process that reflects the construction of the baritone line,

the accompaniment is crafted to "grow" at a different pace. It

unfolds an increasingly complex counterpoint (shared in turn by oboe, clarinet,

violin, flute and piccolo) that blurs the vocal articulation in m. 44. In

contrast to the baritone part, the accompaniment moves clearly to its apex and

utmost registral expansion. The shared forte dynamics and simultaneous

attack on beat two of m. 47 reinforce the sense of previously divergent parts

now teaming-up to extend the phrase. But the reconciliation is denied fruition

by the disintegration of the entire passage into the downbeat of m. 50. The

melodic accent of the phrase is channeled into the structural accent of the

movement.

The disintegration of

the accompaniment (depicted by a reduction in forces), is also weighted by a

motivic reinterpretation. The apex

recalls the characteristic rhythm of the lilac motive (with its upbeat

motion) but in this case, instead of offering impetus to the phrase, it is

employed in the close of the brief flourish. The limited duration of the

episode is framed by the expressive indications that call for un poco

animando and calmando in the space of one measure.

As

the accompaniment evaporates, the vocal line (mm. 47-49) supplies material that

integrates previously isolated melodic events to weight the arrival of m. 50.

In the upper register, a variation on the expressive middle of the subphrase

(mm. 43-44) is reinterpreted to articulate the phrase end. The melodic approach expands the subphrase

middle to place an intervallic expansion of the previous subphrase end (f'-g)

on the downbeat of m. 50 (see Example 25).

Example 25: Parallel

Relationship of Subphrase Endings

At that moment, the ear

registers the parallel relationship between the subphrase ends. The tritone of

"rich green" is echoed by "I break."

The

event is reinforced by a linear connection. The carefully prepared stability of

the fifth, E-B, at the beginning of the phrase moves into the tritone, F-B, at

the end of the phrase and provides maximum harmonic contrast . The linear

displacement of the E is first suggested in the compound melody by double

neighbor emphasis on f in m. 43. The e' and f#' converge on f’ which is then

isolated by skip. The vocal line is echoed in the bass to weight the arrival on

f in the downbeat of m. 44. Finally, in the previously cited midphrase close

off (m. 46), it occurs in the right register but without clear cadential

support. By m. 46 the e has been replaced by f and the arrival in m. 50

provides, a truncated confirmation of the linear event.

The

voice-leading and harmonic structure employed to articulate m. 50 is supported

by the emergence of twelve-tone identities in m. 48. In previous instances, the

row was employed as the ultimate harmonic reference to clarify a formal

arrival. Its effect in m. 48 is different however, since the appearance of P10B

violates this precedent. The sudden placement of the timbre change to winds to

bring out P10B (and its extension by voice exchange) is unexpected.

The orchestrally reinforced hexachordal clarity (amid the freely chromatic

writing of the phrase) is not restored and is instead thoroughly unstable. Its

association with phrase beginnings and phrase endings is turned upside down to

halt the phrase. The hexachord confirms the dissociation of the E and B by

placing F-B (and F#) in a harmonic relationship. (See Example 26.)

Example 26: E Dissociated From F by Explicit Hexachordal

Statement, P10

In the

anacrusis to m. 50 the baritone begins an explicit row statement that recalls

m. 4 (in the soprano) and m. 44 (not serially but in contour and

function). Both references are

incorporated into what becomes not an outgrowth or development, but an ending

mirroring the closing off that occurs with the lilac motive in the

accompaniment in mm. 47-48. The segment concludes in mid-row,

"broken" on order number nine. The more familiar reference prepares

this event, but the event itself requires particular treatment: the

interruption in m. 50 is intensified by the introduction of a partition that

moves beyond the hexachordal polarities and relates the beginning of the phrase

with the events in m. 49. The persistent C#-D# associated to some degree with

stability (WT-A) is now unstable in its pairing with B flat and D (see Example

27).In spite of the harmonic accent, the vocal phrase ends unsupported on the

downbeat of m. 50. The silence that follows intensifies the finality of the

interruption.

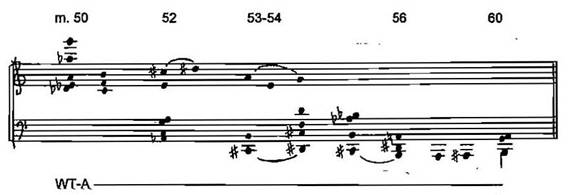

Example

27:

Harmonic Motion of the Phrase

For

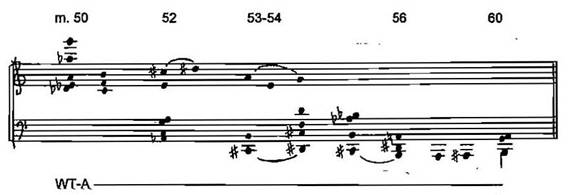

the first time, the orchestra responds directly to the singer instead of

overlapping vocal articulations in a polyphonic web. The orchestra response is

a stark, one-part gesture consists of a variation of the lilac rhythm Parallels with earlier material are evident

in the orchestra response The emphasis on neighbor-note motion and the pitch

pairings( D flat -C, F-E flat, A flat -G) recall mm. 1-2, but given the

context, these P0 associations are heard as maximum harmonic

contrast. To reinforce the break in continuity, the orchestral response picks

up the register that was previously cut off and instead of reinstating activity

there, the contrasting material descends rapidly to the downbeat of m. 52. The

energy of the vocal arrival on the downbeat of m. 50 and the heavily-accented

answer is rapidly liquidated in the following transitional interlude. The

passage is unlike the previous interludes in the way in which it negates

development and transforms the head-accented orchestral outburst into an upbeat

to m. 61. (See Example 28.) The interlude is based on two register transfers of

a harmony based on the WT–A collection (see Example 29).

Example 29: Register Transfer of

WT–A

The WT–A collection dominates in the

background while a WT–A melody is stressed in the foreground.

The design ensures that the octave transfers of the harmony do not, as in

earlier instances, participate in different polyphonic strands. Linear

development is negated in each register.

Example

28: When

Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d mm. 49 - 61

© 1974 Merion Music, Inc.

Used By Permission

A

contrast is perceived on the downbeat of m. 52, but this effect is defeated by

the melodic emphasis on C#-D#. The neighbor-note pair denies melodic

development and despite the rhythmic augmentation, is heard as a parallel

statement to m. 50 (recalling A–B). By preserving six common-tones, the octave transfer of the

harmony supports the perception of a parallel event simply moved to a lower

register. The forward momentum is further depleted in the C#-D# figure by substituting

rhythmic squareness for potential development.

The

passing harmony (m. 53) and melodic skip to A natural provide a metric accent

on the downbeat of m. 54, but this is supported by the second octave transfer

of the WT–A harmony (which contains the C#-D# transferred to the bass). The

scoring emphasis on the A natural (fl., alto fl., ob. I+II, eng. hrn., E flat

cl., B flat cl., marimba) is neutralized by the harmonic and melodic

expressions of WT–A. The harmony gained by the second octave transfer is retained

beneath the A-G linear motion in m. 54. The repeated E-G (English horn, oboes,

and at the outset, clarinets) dissipates the energy further.

This harmonic and

relative melodic stasis is partially relieved and subsequently directed by the

emergence of a linear statement of R8 in mm. 56-60. The appearance of the row

is consistent with its employment at other formal junctures in the movement as

a tool for gauging harmonic "distances." The statement is supported by the bass that

works toward the WT–A harmony of m. 60 (G#-G-F#-G#-A in one voice, A-B flat (A#)-B

in the lowest voice) and the bass motion

provides leading tone emphasis to the B natural that has been present in that

register since m. 58. However, even with the dynamic accent (decrescendo

from ff to pp) and the leading-tone inflection, the motion to B

natural is relatively weak. By emphasizing the pitch with chromatic

neighbor-notes as opposed to a directed bass line, the harmonic arrival in m.

60 does not create an overt rhythmic accent.

As

the interlude unfolds, each register transfer represents an opportunity for

harmonic contrast. Each time contrast is denied, expectations for such contrast

increase. The search for harmonic contrast is heightened by the row statement

that contributes melodic direction to the anacrusic passage. As in earlier phrase constructions, one is

led to expect that harmonic change will coincide with, and provide impetus for,

the upcoming entry. Since the arrival in m. 61 is preceded by the same chord as

an upbeat, this phrase opening is deprived of this particular at type of metric

accent.

The

denial of contrast here functions in a larger role because of the way it uses

established harmonic references. Throughout the movement the WT–A collection

has been employed in the role of phrase opening or as an upbeat. Even with the

context switched (as in m. 50, where WT–A serves as the goal of the phrase),

factors already cited make the WT–A an unstable arrival. In the interlude the

instability of the collection is intensified by the refusal to develop and the

refusal to proceed to a harmonic contrast. By denying harmonic contrast on the

downbeat of m. 61, the unresolved energy and accumulated expectations of the

previous material and events are suspended. The infused tension is maintained

throughout the final period.

Conclusions:

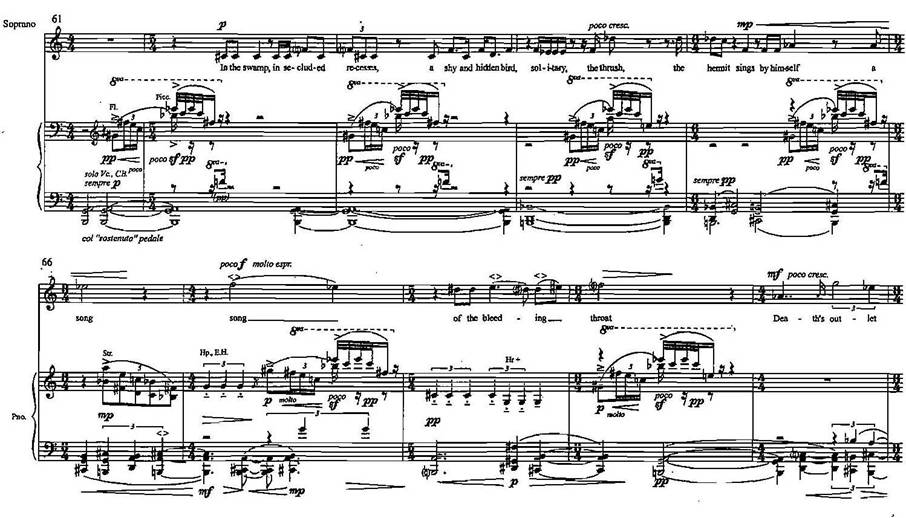

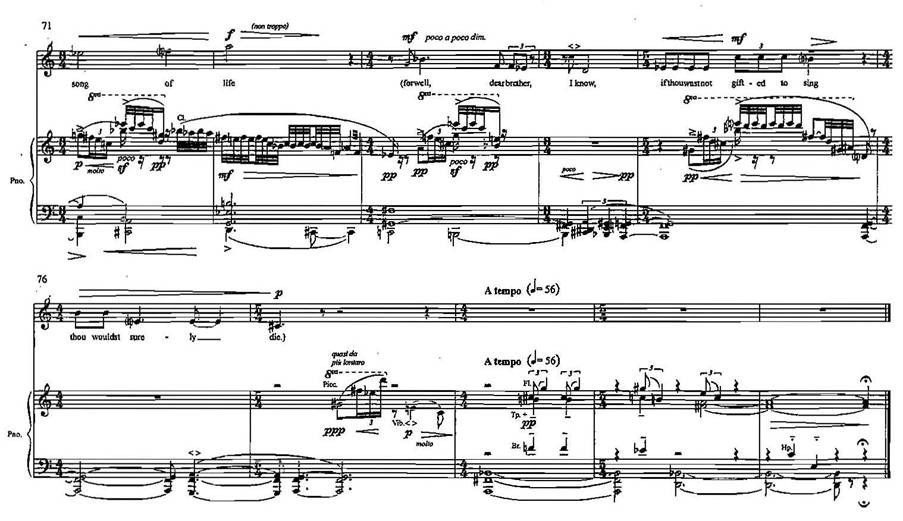

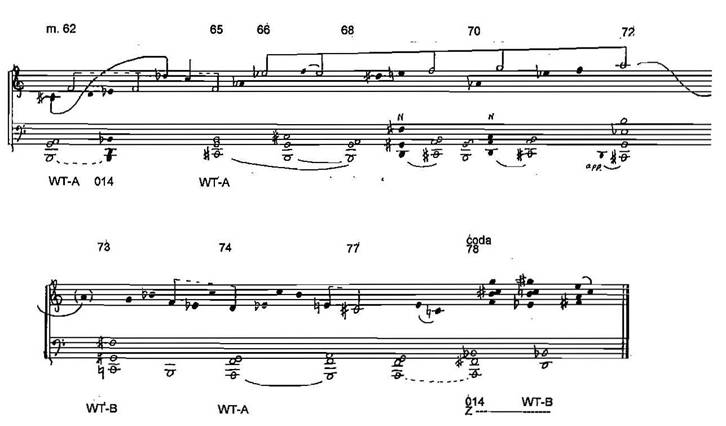

Soprano Recitative, Measures 61-80

The

beginning of the final passage effectively captures the moment of arrest

experienced by the poet when the bird's song, "in the swamp, in secluded

recesses," reaches out to penetrate his inner world of grief. The text is

placed in high relief and transformed into a poetic island by its setting as a

self-contained passage. After the

truncation and highly charged response of m. 50 and the insistent but harmonically

languid interlude, the closing period is further stripped of song, orchestral

forces and even pulse. All that remains is the bird call. The piccolo and flute

(from behind the stage) muted trumpet, celesta and marimba present the call of

the hermit thrush with harmonic support from a solo ‘cello and a solo

contrabass. The literal quote of the thrush is unexpected and confirms that the

musical line is indeed severed: the bird sings freely while the singer (poet)

can only speak.

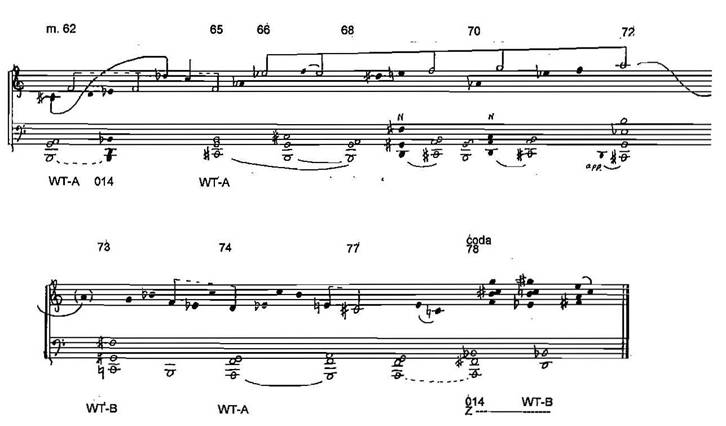

The

denied contrast on the downbeat of m. 61 is extended to form a harmonic block

that controls the entire recitative. The WT–A harmony (I11) and

subsequent expectations are frozen into a static configuration by the entrance

of the WT–B bird call. The registrally exclusive collections behave like poles

of two magnets and repel each other while the soprano completes the aggregate.

The pitch material of the soprano, the shifting harmonies and the bird call all

give up a pitch-class or two intermittently, reacting to one another, but

maintain the locked stasis. The underlying WT–A collection in the accompaniment

is embellished with neighbor-notes, voice exchanges, and the 014 trichord

(recall other instances of the 014 functioning between whole-tone expressions).

Any harmonic contrast in the period serves to extend WT–A. The prolongation

does not establish a pulse; it shifts unpredictably. The suspension of pulse in the accompaniment

means that the surface rhythm is restricted to that of the soprano's natural

speech inflections. The bird call is also without pulse and enters at will over

the course of the passage. The general length of the call (with slight

variations) works contrapuntally to provide cross-accents against the soprano

and accompaniment. The soprano entrance relegates the bird call to the role of

embellishment. (See Example 30.) The cadence that concludes the recitative can

be considered independently from previous cadence formations. Without the

resource of harmonic motion as employed in all other cadential articulations,

the recitative relies on alternate means to generate directed motion to the

final cadence on the downbeat of m. 77. Amid the saturated WT–A harmonic

structure, the shape of the vocal "melody" is largely responsible for

a convincing arrival.

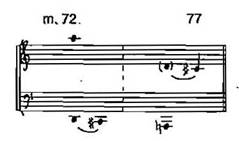

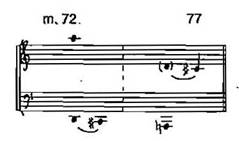

The soprano

recitative consists of one phrase (mm. 61-77), a formal arch, that subdivides

at the registral climax in m. 72. The opening of the soprano "melody"

(mm. 62-64) differs from the characteristic expanding interval construction. Here

the third (spelled as a diminished fourth, C#-F) is contracted to a

major second as the measures unfold. The contrasting procedure generates

tension that gives rise to the movement away from the fixed register at the

point of the Db(C#)

octave transfer in m. 64. As it approaches the climax, "song of

life," the melodic character reflects a brief manifestation of the lyrical

impulse.

The melody

is based largely on the WT-A collection, and because there is little tension

between the harmonic basis of melody and the harmonic basis of the

accompaniment, the urgency of the earlier writing is absent from the

recitative. This is reflected in the melodic accentuation of the period. The

climax in the vocal line, A, is achieved without any kind of semi-tone inflection

(that is, a chromaticism with regard to the WT–A collection). It is simply a

continuation of the WT–A melodic activity in that register. The expressive

accent on the A is not articulated by a change of harmony that makes the apex

stand out against the prevailing WT–A background. A slight inflection of the

WT–A harmony occurs on the downbeat of m. 72 with the D-C# appoggiatura (C# is

WT–A). The one harmonic change that does occur (m. 73) happens between two

expressions of WT–A and points away from the soprano climax to set up the

concluding segment of the text. (See Example 31.)

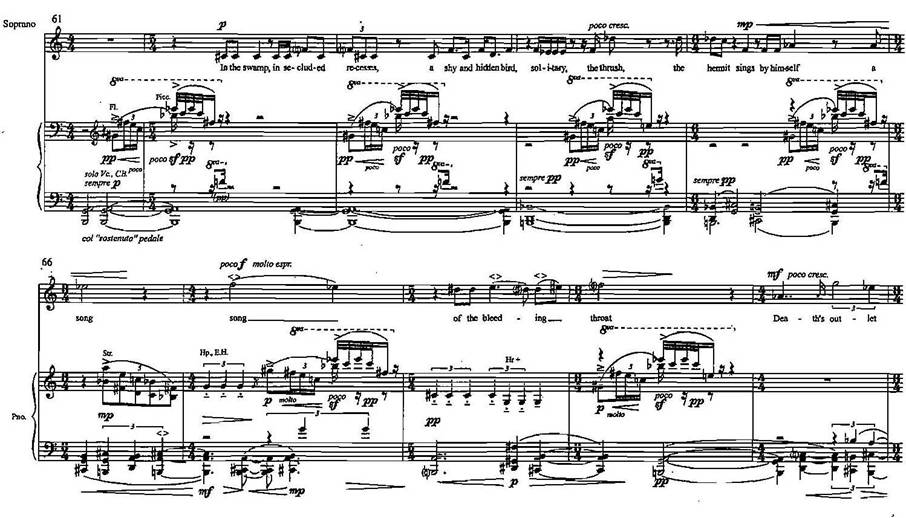

Example

30: When

Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d mm. 61 - 80

© 1974 Merion Music, Inc.

Used By Permission

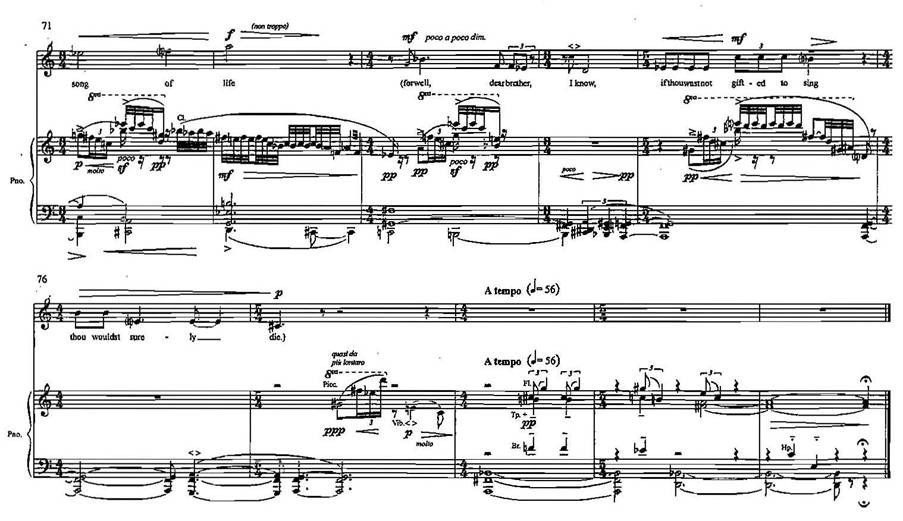

Example

31: Reduction of mm. 61 - 80

The

soprano arch is set against an accompaniment structure that subdivides, mm.

61-67 and mm. 68-77. The prominent B harmony (B-G-A) of mm. 60-63 returns on

the downbeat of m. 68he accompaniment (muted strings, English Horn, French

horn) reflects the developing lyrical impulse in the vocal line and pulls

through any articulation of the harmonic return to provide a metric accent in

support of the soprano arrival on F in m. 69. As part of the WT–B harmony in m.

68, the D functions as an upper neighbor to C# which returns to B (WT–A) in m.

69. The D-C#-B is repeated with harmonic intensification in m. 70. In its final

appearance, the D, beginning as the appoggiatura on the downbeat of m. 72,

descends through C# to C and the metrically accented WT–B harmony (m. 73). The

B in m. 73 returns in an altered harmonization and is treated as a passing tone

in the line that continues through the B flat to the A (and the return of

WT–A). In conjunction with the D–A bass descent, the concluding text

installment is set in the soprano as a descent from A (octave transfer implied)

to D in m. 74 (see Example 32).

Example

32a:

Linear Cadential Structure

The

vocal melody of mm. 75-76 prolongs D and delays the cadential arrival, C#. The cadence is a variation on the treatment

of the registral climax. (See Example 32b)

Example

32b: D-A emphasis

Harmonic

contrast is not employed to accent the structural downbeat. The arrival of the

cadential harmony (WT–A), anticipates the cadence by two measures. The sole

rhythmic emphasis on the cadential downbeat is supplied by the soprano C# (and

the bird call is altered to participate in the structure and supply an

afterbeat flourish). In addition, the cadence is not qualified, as in the

earlier cadence formations, by the presence of the fifth which transcends the

symmetrical collection. The effect of this cadence, in which some of the

elements are deliberately placed out of synchronization with the metric

arrival, is that the phrase simply stops. The music "dies." A

concerted drive to cadence is not a condition that can or should be met

within the limitations of this particular recitative. The cadence on C# clearly

relates to the opening C# (m. 62), and this makes it difficult to extend the

relevance of the cadence beyond the boundaries of the final period.

The

stability of the vocal cadence on C# is immediately challenged however, by the

coda. The pitch is displaced by the vibraphone echo, E-C natural. The

intervallic expansion (E-C# to E-C) is a return to the characteristic motivic

procedure previously associated with harmonic change. The E-C dyad also

anticipates the final harmonic move to “Z” and provides a foil for the entrance

of the WT–A lilac motive. The A natural in the bass, part of WT–A in the

recitative, is retained and cast in a contrasting harmonization when it becomes

part of the 014 (“Z”) trichord with the addition of Bb-F# on the downbeat of m. 78. These pitch-classes

represent a striking registral and contextual addition since their employment

in the passage was restricted to the bird call.

The

quotation of the lilac motive provides a recapitulation of the WT–A harmony of

the recitative and confirms the WT–A cadence, but because it is placed in a new

harmonic context by its entrance over the “Z” trichord, it is subservient to

the motion to “Z” begun with the E-C of m. 78. While the return of musical

symbols in the coda confirms the "trinity" (“life”, “death”, and “the

thought of the poet”) the extended WT–A recitative, explicitly linked to “life”

by the return of the WT–A lilac motive, defers to “death” and obscurity in the

final “Z” chord. The song of the thrush represents the "possibility of

poetic utterance," but here this

truth remains impalpable, concealed by the "harsh surrounding

cloud."

The

lilac motive picks up the b' natural left by skip in the vocal line and moves

it to a' (m. 79). The octave transfer of the A–F# from the bass coincides with

the arrival of “Z” as a consequence of local voice leading, and the marimba is

used to punctuate the attack. The final “Z” chord is also weighted by the

return of the tutti cellos and contrabasses. The alto flute and clarinet recall

the original motivic alteration, and the return of alto flute frames the

coda. The fifth in the outer voices

brings an aspect of the previous cadential formations to bear on the final

chord by adding stability to the “Z” harmony.

As the coda opposes the cadential pitch of m. 77, it confirms the D-A emphasis

that was part of the cadence formation and, recalls the “Z” appearances of m.

5, m. 19 and m. 22. The goal of the first period suggests the motion of the

movement: m. 19 is confirmed in m. 80.

The

“Z” orientation of the coda anticipates the opening of the second movement. By

retaining the common tones D-A (in register), the second movement begins from

the tonal anchor established in the “Introduction.” The persistent upbeat

quality of the “Introduction” gives way to an incipit accent that conveys the

weight of the lumbering funeral train. The downbeat of the second movement

starts a journey distinct from reminiscence. The “funeral train” harmony that

begins the second movement controls a considerable time-span; it returns

fifty-four measures later to link the train to the bells “perpetual clang.”

The

closing recitative texture of the Introduction arises in response to, and a

result of, the severed musical line. Its historical association with

introduction and its unexpected formal placement as the close of the movement

maintains the anacrusis generated by the preceding music. The "Introduction" is, ironically,

concluded by an introduction and the purpose of the cadence and the coda, and

the purpose of the movement as a whole is not to resolve accumulated tension

but rather to perpetually direct it into the beginning of the second movement.

Bibliography

Cone,

Edward T. "In Defense of Song: The Contribution of Roger

Sessions." In Music a View

from Delft, ed.

Robert P. Morgan, 303-322. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

–––––––––.

"Conversation with Roger Sessions." In Perspectives on American Composers,

eds.

Benjamin Boretz and Edward T. Cone, 90-107. New York: W.W. Norton &

Company, Inc., 1971.

Feidelson, Charles Jr. "Symbolism in When

Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd.."

In Critics

on Whitman, ed. Richard H.

Rupp, 66-67. Miami: University of Miami Press, 1972.

Imbrie, Andrew. "In Honor of His

Sixty-fifth Birthday." In Perspectives

on American Composers,

eds. Benjamin Boretz and Edward T. Cone,

59-89. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1971.

–––––––––.

"The Symphonies of Roger Sessions." Tempo, 103 (December 1972), 24-32.

Kinkead-Weekes, Mark. "Walt Whitman

Passes the Full-Stop by..." In Nineteenth-century

American Poetry, ed. Robert A. Lee,

43-60. London; Totowa NJ: Vision; Barnes and Noble,1985..

Mackey, Steven. The Thirteenth Note.

Ph.D. diss., Brandeis University, 1985.

Merryman, Marjorie Aspects of Phrasing and Pitch Usage in

Roger Sessions' Piano Sonata

No. 3.

Ph.D.

diss. Brandeis University, 1981.

Olmstead, Andrea Roger Sessions and His Music. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research

Press,1985.

–––––––––. Conversations with Roger

Sessions. Boston: Northeastern University Press,1987.

Powers, Harold S. "Current Chronicle." The Musical Quarterly, 58 (April

1972), 300, 302, 304.

Sessions, Roger. Harmonic Practice. New York, Burlingame: Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc.,1951.

–––––––––.

Roger Sessions on Music, Collected Essays. Edited by

Edward T. Cone.

Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1979.

Whitman, Walt. Leaves of Grass. Edited

by Harold Blodgett and Sculley Bradley. New

York:

W.W. Norton and Company, Inc., 1968.

1 These are

the dates on the vocal score. The commission came in 1964. For more details of

this nature see: Andrea Olmstead, Roger Sessions and His Music (Ann

Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1985), 157-162.

Harold S.

Powers, “Current Chronicle,” The Musical Quarterly 58 (April 1972), 300,

302, 304.

3 In the following