Example

1:

Ogdon Third String Quartet, Second

Movement Cavatina 1 mm. 1 – 12

Form and Moment:

Will Ogdon's String Quartet #3

John MacKay

Alternatively titled "String

Quartet in Five Movements," Will Ogdon's Third String Quartet stands out among his larger works in its combination

of a rich and often aphoristic lyricism with an inventive manipulation of

classical twelve-tone thematic process. It consists of either five or three

movements (the three-movement form merely leaving off the first and last

movements, see Figure 1 below) and projects a unique and finely tuned balance

of "momentary" reference within and between movements.

I II III IV V

Allegro 1.

Cavatina

2.

Scherzo

3.

Cavatina

4.

Scherzo

5.

Nocturne

6. Poco

Scherzano

(-

Trio - Poco Scherzando)

Figure 1:

Formal Scheme of Ogdon's String Quartet #3

In addition to the

distinct formal impressions of the two versions, there is also the interesting

case of its second movement, a six-part, pendular arrangement of lyrical and "scherzo"

characters which traces a miniature formal dynamic within the larger scheme.

The outer movements, written after the others, pose a further level of autonomy

and interaction; the intricately taught and focused sonata design of the first

movement recasts, and, in the actual sequence of movements, anticipates, the

essential ideas of the other movements, and the closing “andante” summarizes

and concludes yet somewhat at a distance. For the present discussion, it will

therefore be helpful if “the first will be last” since the loosely serial

structure of the work is more transparent in the initially composed sections of

the second movement.

Movement II: Cavatina Scherzo Cavatina Scherzo Nocturne Poco Scherzando (Trio - Poco Scherzando)

The individual “movements”

of the second movement are essentially all in three-phrase ternary structures

in which a closing return or suggestion of opening ideas frames a contrasting

or digressive central fragment. Moreover, all ”movements” in Movement II except

for the Scherzando/Trio, and indeed all the other movements in the entire

quartet, end in a delicately nuanced tremolo sonority which becomes a recurrent

fixation throughout the entire piece. The motivic language of the work evolves

both concretely and abstractly from the 12-tone premises of the

Cavatina/Scherzo alternations where at least two distinct series are projected

amid incidental accompanimental/harmonic elements as well as significant and

apparently autonomous figures which intervene at various points in the form and

underlying narrative.

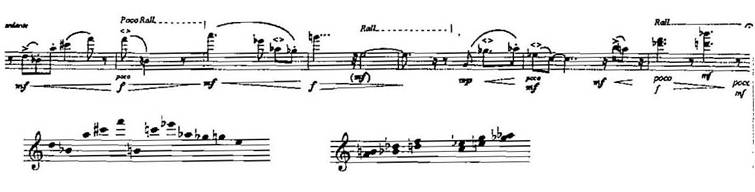

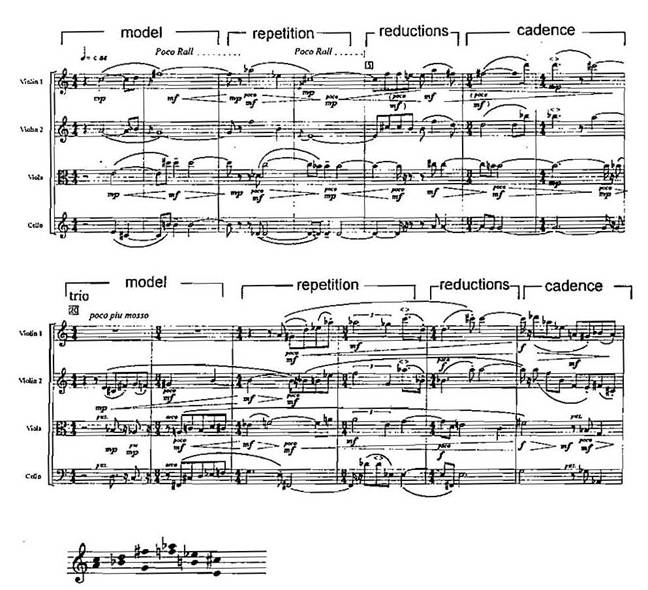

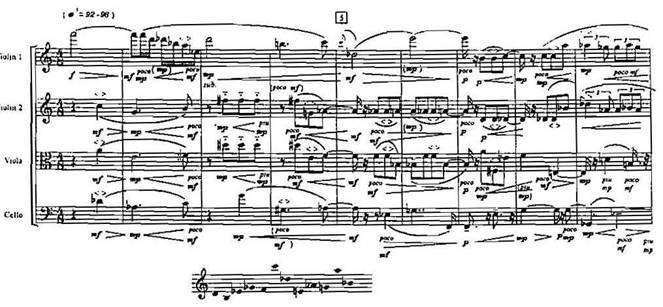

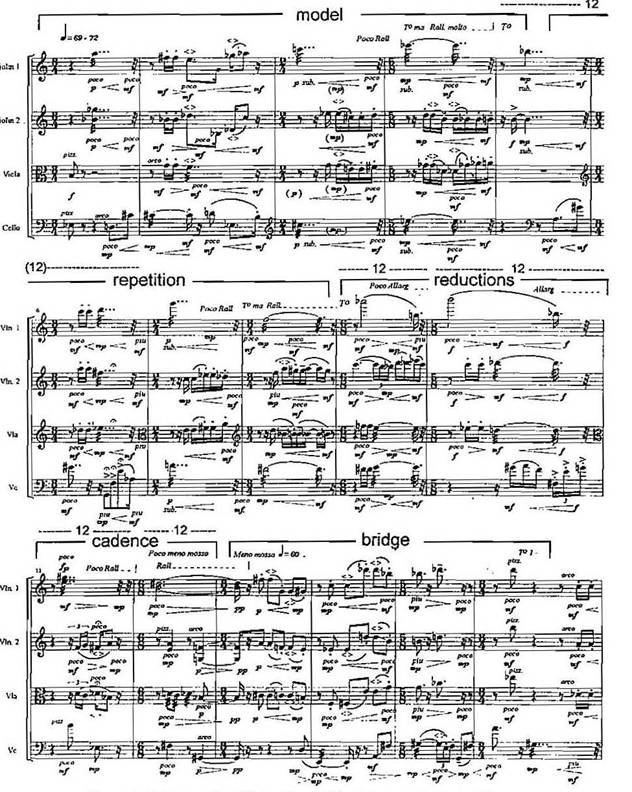

Example

1:

Ogdon Third String Quartet, Second

Movement Cavatina 1 mm. 1 – 12

Thus many elements from the row of the

first Cavatina can referential if not thematic (see Example 1): the B-D and E

flat-G flat minor thirds, the major/minor triadic combination which they

comprise, and also the chromatic tetrad (A flat-G/ A natural B flat) which

completes the row and which guides the descending imitations through the

cadence on C natural in m. 10. While the

initial pizzicato commentary in the viola and ‘cello in sevenths and momentary

sixths (m. 8) provides relatively free harmonic orientation, it also touches

upon important ideas such as the A-B dyad in the harmonics of m. 7 which is

outside of the 12-tone context created in the violins.[1]

The brief “streaming” in

thirds/sixths in the central piu animato

fragment (mm.10 -13) continues outside of the initial 12-tone orientation but touches

upon, as we will see, elements of the 12-tone structures of subsequent sections

of the movement in its gentle G flat-A flat oscillation and its p sub. tremolo on D flat-A. In echoes of

the minor third elements the melodic contour of mm. 14-18 gracefully reverses the

earlier descent of mm. 13-14 via D flat- B flat, in m. 14, A-C in m. 15, A flat-F

in m. 17 and the C-E (the major third octave transposed from the cadence of m.

10) to the G flat-E flat and finally the D-B natural which evoke a partial

return of the original 12-tone theme. The closing sonority on E flat, F# and D, sustains

these elements (minus the B natural) in the harmonic tremolo the end of the

movement.

In a natural contrast to the floating

delicacy of the "cavatina"s the "scherzi" are witty and

clearly phrased. While the first scherzo

begins with the minor thirds of the first cavatina, it immediately forges a new

serial structure (see Example 2) as well as significant new associations of

concrete pitch elements. Of these the B natural A is repeated in the serial

unfolding between the viola and first violin as part of the outlining of the

augmented triad A-C#-F, to which the viola responds with the A flat-G flat,

completing the series and outlining a further augmented triad (A flat-E-C) in

the cadence on C in m. 8 which is punctuated with the conflicting fifths A-E

flat/A flat-E flat. It links via the

major/minor triadic structure in the violins (the B flat-D flat/ D natural F)

to the central fragment where once again a melodic interval stream (in major

seconds/minor sevenths, coloring the F#-E in harmonics) emerges and breaks off

again in the pre-emptive major third E-G# in tremolo before the return of ideas

from the opening 12-tone structure. The return however is tentative, skipping

the opening figure and recalling at first only the second motive (the viola’s

D-B natural, B flat -A) and the G flat-A flat, now clearly linked to the F,

before regressing to the oscillating minor thirds E-G, E flat-G flat from the

close of the first cavatina. The closing motions of the scherzo unfold

major/minor triads on B flat and C natural and recall the intrusive E-G# of the

central fragment. The second fragment of the series echoed between the

violins is altered in the first violin, shifting the D natural to E flat and

the closing tremolo on E-G-E flat once more reflects the opening tetrad but

minus one of the tones (the C natural in

this case).

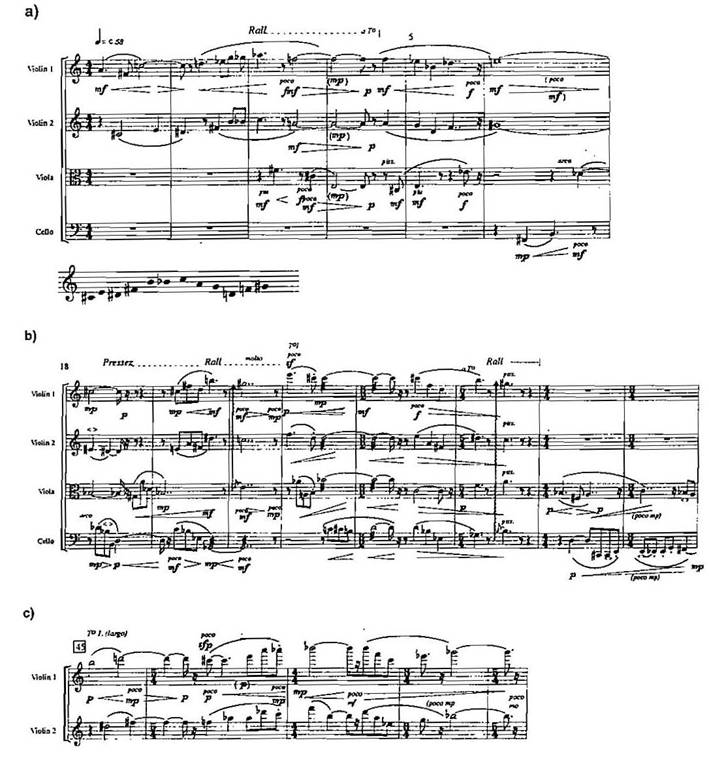

Example 2:

Ogdon Third String Quartet, Second Movement

First Scherzo (2) mm. 1-9, Second Scherzo (4) mm.1-6

Example 3:

Ogdon Third String Quartet, Mov’t,

Cavatina 2, mm. 1 – 7 and Series with

Component Hexachords

The series

of the second cavatina opening with its chromatic major thirds, D-B=/ A-C# (note with the ensuing

F natural which, minus the A natural, forms the major/minor triad) recalls

earlier associations from the first scherzo in the A-C#-F augmented triad and

the A flat-G flat connection which now separates the minor thirds C-E flat and

E-G. In the overall working of the tonal language of the Quartet the series of the second cavatina establishes thematically

the two (complementary) hexachords of the B= major/minor triad (B=-D=/D-F) plus A-B natural and the

C major/minor triad plus G=-A= (see Example 3). In this respect,

it is interesting that the row is altered in its initial presentation, giving a

high A natural following the B instead of the C which is confirmed in the

subsequent retrograde form; while this may be indicative of Ogdon’s concern for

momentary tonal and linear nuance it also witnesses the “intrusive” significance

of the A-B element, seen also in the oscillating figure in the ‘cello’s

accompaniment (m. 3) at the close of the series and the reordering of tones in

the retrograde (m. 5) to present A-B natural in a quick slur and group the F

into the B flat major/minor sonority at the first cadence in the violins in m.

6. The intervening fragment again streams intervallically, in major thirds,

forming major/minor triadic outlinings in their transient arpeggiations and

once more cadencing on the E-G# of the previous scherzo. It is joined here by

the ‘cello C# in a momentary but substantial triadic nuance which echoes the independent

B-A-B-C# element from the ‘cello in m. 3 (the ‘cellos oscillating motive shifts

to D-F-A= in m. 5). Then, mixing

seconds and thirds in a suggestion of the middle tones of the scherzo series

the interval stream in the violin, with a further interjection of the A-B

natural 7th in the ‘cello seems to come to a premature cadential tremolo

(E flat, F# F natural) in the upper strings). The first violin however continues with the series

as at the opening (again with A natural instead of C natural) against a further

brief tremolo (the G flat/A flat element in the viola and violin, and F natural

D in the ‘cello) and a further echoing of the ‘cello’s A-B natural and closing

pizzicati against the violin’s tremolo mid-register E natural al niente.

The second scherzo provides an essentially free reprise of

the first, but uses the retrograde of the row of the second cavatina. The series

is somewhat disguised by the occurrence of the E flat and C, series tones 5 and

6, in the pizzicato commentary which is otherwise typically free of serial

function in these movements. Similarly the second motive of the first scherzo’s

series appears altered, the D-B flat-B natural-A, changed to D flat-B flat-B

natural-A and the internal tone repetition within the unfolding series now

covering three tones - A-B-C#, completing the series with the harmonic F natural

and the pizzicato D natural (and also perhaps the B flat as a repeated tone in

the series, see Example 2) once more uncharacteristically from the accompanying

pizzicati. The series continues through the cadence again on C (m. 4) slipping

its B flat - A natural seventh to an A-B major ninth (m. 6) before liquidating

fragmentations from the current series

and, also from the closing development of the first scherzo: - the derived F-G flat-A flat group, the alternating

E=-G= thirds

(originally from the first cavatina) and the climactic major third E-G#

approached anticipatorily with an ascending tremolo line in the first violin

from C natural through ascending major thirds B flat-D (m. 12) and E flat-G (m.

13-14) [2]

superimposed on the unfolding of the series from the beginning of the movement

in the second violin. The movement closes with the same E-G-E flat tremolo as

the first scherzo however against pizzicato B natural-B flats instead of the G

sharp B of the first scherzo.

Example

4:

Ogdon Third String Quartet, Second Movement

Nocturne (5) mm. 1-11

The graceful change of pace, in temperament and

harmonic texture of the “Nocturne” maintains a lucidly classical phrase structure:

its gentle triadic shifts in the upper instruments support the solo 'cello line

as it alternates pizzicato and arco motives in a two-measure model, varied (mm.

3-4, see Example 4) and developed imitatively with the viola in the guise of a

thematic sentence. The 12-tone structure of the theme and accompaniment is

articulated initially (mm. 1-2) according to the four augmented triads which

slips in m. 4-7 to more recognizable associations with the 12-tone premises of

and “moments” of the second cavatina and scherzo: the B=-D-D=-A-B grouping in the upper strings

in m. 4 (from the opening of the series) the ‘cello’s A-B-B=-D= (m. 5) and the viola’s A=-G=-E-G (mm. 4-7) and the C-E=

of the series being sustained in the violins (mm. 6-7). The central interval stream

(mm. 8-11) similarly paraphrases the cavatina 2 series with the interval stream

extension (in thirds/sixths) culminating in the C major/minor sonority of the

beginning of the scherzo 1 series and the D flat - A natural now easily identifiable

with the scherzo and cavatina 2 series, although as a “moment” it specifically

re-interjects the D=-A tremolo from

the central fragment of the first cavatina. The return of the sentence in mm. 12-18 is adjusted

to include the E natural in the ‘cello against the C-E= in the violins recalling the

C major/minor sonority of mm. 11-12 before melting unexpectedly into the D-C=-D=-F tremolo of the close.

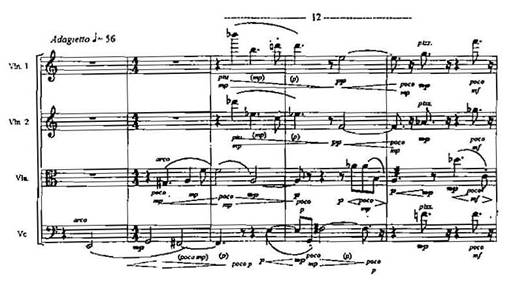

In a type of 2-by-2 part invention (see Example

5 below) the "poco scherzando" focuses and expands the harmonic

streaming from the previous “central fragments” of the cavatinas, scherzos and

the nocturne. Also in a sentence (mm. 1 -8) and short ternary form, a short

bridge sets the 'cello, as in the "nocturne" against the upper

instruments. The poco scherzando series is structured in thirds in the violins in

mm. 1-4 against its more or less retrograde in the viola and ‘cello. Note the alteration to major thirds in the

reductions of the sentence (A-C# instead of A-C and F-A natural instead of F-A=) and the reassertion of

E-C# at the cadence in m.8 against the G-F# which was missing from the near

retrograde in the lower strings. The abbreviated return of the sentence in mm.

15-19 reduces the 12-tone structure to superimposed hexachords placing tones

1-6 in the violins and 7-12 in the viola and ‘cello however replacing F-A= in the latter with E=-G and inserting a lengthy

and (and as we shall see) significant leading-tone A= to A natural in the in the second

violin against the C natural sustained in the first violin.[3]

The “trio” mixes the dyads of the poco scherzando series with suggestions of

the earlier series in free combination and chromatic alteration of elements. In

the very large scheme of the entire quartet, the reduction in the nocturne and

absence in the poco scherzando of the

isolated and closing tremolo sonorities lends a temporary calm and relief from

this otherwise subtly ever-present suggestion of luminous tension. The closing

sonorities of these sections (sustained in the upper strings against pizzicato

punctuations in the ‘cello) are also interesting: a B flat major triad in the

trio and A-C#-C>in the poco scherzando.

`

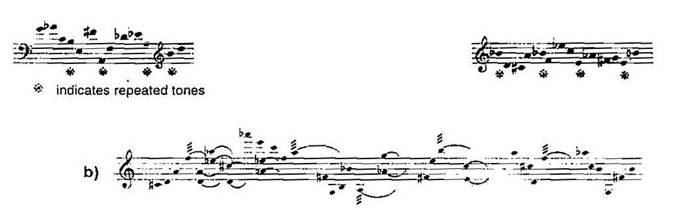

Example

5:

OgdonThird

String Quartet, Second Movement Poco Scherzando (6) mm.1-7, Trio, mm. 20 – 25

Movement

III:

The 2-by-2-part model of

the poco scherzando persists with apparent references to its series in the expansive

The theme of the movement

(mm. 1-17) forms a ternary “lied” structure: the bridge fragment (mm 9 - 12)

comprising a brief liquidation and contrasting cadential sonority before the

return of the thematic series in the violin initiated by “off” tones G (instead

of A) in the first violin and F (instead of C#) in the second violin. The theme

liquidates (see Example 6b) via a three-eighth-note motive from the contrasting

segment, transposing and inverting the final four tones of both series and transforming

the earlier E-G# cadences (m. 6 and also 16-17) in the staggered unfoldings of

m. 22 (note the distant suggestion of

the tremolo color in the ‘cello) and, after a new derivation from the E-C# head

of the series, in the pizzicati of m. 25 in which only the G# remains in the

sonority.

Fracturings, deviations,

and progressive liquidations of the series persist a new piu animato and contrapuntally active character in the central section.

It’s focal event however is the return

to Tempo 1 at m. 45 with the two series up a tone transposed to begin on D# and B natural and reference the opening

of the series of the first cavatina; note the alterations in the lower series

of the E natural to E= in the final four

tones (see Example 6c). The subsequent return to the opening materials is eliptic,

skipping the “lied” structure return of with a variant of the m. 26 opening of

the central section (see Example 6b) and a muted recall of one of the series

liquidations of the central section before the intervention of the closing

tremoli from the end of the poco scherzando

however resting finally on the A=-C

instead of the A-C of the earlier moment/movement.

Example

6a, b, c:

OgdonThird String Quartet, Third Movement,

Movement IV: "Recitativo"

In contrast to the developmental

depth of the third movement, the fourth movement "Recitativo" presents

one of the most straightforward and transparent formal structure of the

quartet; a thematic "lied" alternating wide-ranging lines in the

‘cello and first violin is contrasted with a short and freely structured

central section leading to an identical return of the opening "lied" and

a brief and fleeting coda into the closing tremolo sonorities recalled from the

contrasting section. The prolongation of the slow tempo through this movement

and the preceding

The series

of this movement give good examples of Ogdon’s adaptation of the twelve-tone

row to specific harmonic and thematic contexts. The opening near- series in the ‘cello (see Example

8[4]) is an inversion

of the series in the violin’s melody (mm. 9-16) which is, with minor re-ordering,

chromatic adjustments and tone repetitions (B= and E natural are

repeated) that of the second cavatina from the second movement. The violin concludes

with a seemingly more “authentic” statement of the ‘cello series without

repetitions of the A natural and a substitution of B= for the repeating B

natural at the end of the series; it too however, inserts a repetitive G

natural in stepwise motion between F and A; it is directed back to the B= of the

descending minor third D=-B=, unfolding the referential major/minor triad with the D natural-F

in the viola with the return of the ‘cello segment. Unlike it’s original

appearance, the return of the ‘cello series is a complete form, substituting a

B= for the

second A natural and, again presenting the first eight tones but closing on G

natural instead of the earlier A=. The slow and delicate chordal accompaniment provides

12-tone complements to the hexachordal structure of the ‘cello and violin

solos. The two accompanimental segments are connected: the ten-chord sequence

in accompaniment to the violin begins with the fifth, sixth, fifth (repeated),

seventh, and eighth (final) chords of the chordal sequence accompanying the

‘cello.

The central section, as in the Largo, pursues

fragmentations from both the ‘cello and violin recitatives (see Example 7c)

projecting momentary stratified tonal implications amid the return of pizzicato

and tremolo colors and the new harmonic element of perfect fifth sonorities. The section culminates on a compound tremolo

sonority D-A/E=-B=-F of chromatic but

fifth-related components against a pizzicato

Example

7a, b, c:

OgdonThird String Quartet, Fourth Movement,

Recitative mm. 1 - 16, “fragments” from central section, ending mm. 57-62

recall of the opening

of the ‘cello melody culminating on B. The return of the opening alternation of

accompanied ‘cello and violin recitatives is without significant alteration

however the tremolo coloration intervenes suggestively at the close of the

violin melody. The coda begins fleetingly

with a pp recall of the beginning of

the retrograde of the second cavatina series in imitation between the first

violin and viola, quickly diffusing however to a closing sequence of tremolo

sonorities: the A=-C major third from

the close of the Largo plus B natural (m. 57) the opening tone of the imitative

fragment (instead of E natural of the cavatina retrograde). The closing sonorities (Example 7c) recall with

semitone shifts (the D-A to C#-G#, and E=-B= to E>-B>) from the fifths of the central

section against closing streams in major thirds suggestive of the beginning of

the series. The emergence of the fifths

at the close of this movement is significant, particularly in the 3-movement

form of the work, as a final shift in the prevalent harmonic color of the work

dominated by chromatic relationships of thirds and sixths.

Movement V: "Andantino"

The final "Andantino"

holds the ultimate steps of the ongoing play of the tonal and textural motives.

For this reason, its form may be more open since it involves ideas which by now

are familiar and require no introduction. In any case, its opening theme (see Example 8a)

is complex and continues the violin/’cello dualities of the “Recitativo” although

now in simultaneous, as opposed to alternating lines. The Andantino begins, in

fact, with an indirect reference to the preceding movement - the descending

line in the violin F-D-D=-B=-A-E= outlines the opening accompanying

sonority of the “Recitativo” (see Example 7a) but proceeds directly to an

unfolding of the cavatina 1 series between the violin l and the inner voices. The ‘cello line however, which eventually

assumes greater motivic independence could be taken to define more consistently

an opening model/repetition format in mm.1-12. The sense of developmental

reduction and cadence however in mm. 12 - 19 is clear in its significant focus

on the tremolo now as a thematic as opposed to coloristic element. Note also

the repeated cadencing on B= elements in the

tremolo sonorities in m. 12 (in response to the earlier rallentando on B-A

natural in m. 10) and 19.

The liquidation of the

opening structure is to the tremolo chord stream of mm. 23 - 26 (see Example

8b) at which point the opening structure returns (mm. 27 - 35) in an altered

form beginning with a rising arpeggiation in the ‘cello (as opposed to the

descending figure in the violin) and restricting the model plus repetition, to

the unfolding of the tones of the first cavatina series - the ‘cello taking the

violin’s opening B-D/C-D= plus G (instead of

E) with the last two tones now in tremolo. The reductions are recessive rather

than cumulative as in the opening and they juxtapose significant elements from

the first scherzo series: the C major/minor triad in rising pizzicato

arpeggiations (a liquidation of the ascending arco sixteenths in the ‘cello

from the opening of this presentation of the theme) with successive glissandi

from the G up to F# and G# against the B= major/minor sonority

unfolded downwards in the violins to a tremolo A/B natural upper mid-register

tremolo.[5]

The reduction/liquidation is complete as the latter tremolo second shifts to F#-G#

in the viola/’cello again the B= minor/major plus

A-B natural elements unfold in the violins in ascending pizzicatti and

sustained tremoli.

Example 8a:

Ogdon Third String Quartet, Fifth Movement,

mm. 1-19

Example

8b, c, d:

Ogdon Third String Quartet, Fifth Movement,

mm. 23 - 26,36 - 40, 63 - 67.

The essential linear and

harmonic coherence of the final passages (mm. 36 - 67) continues in the specific

series elements in combination with generally third-based structurings such as

the major/minor sonority, the “contained” major minor third trichords (014) of

the tremolo/pizzicato sonorities, chromatic minor and major thirds, augmented

and diminished triads, the seventh chord groupings (as in the tremolo stream in

mm. 23-26, see Example 8 b) as well as simple doublings of referential elements

in sixth or thirds. The coda in m. 35-36 begins with a model Example 8c) which

introduces these tendencies (note the interval patterns plotted below the

example, the latter interval group consisting of a diminished triad within a

perfect fifth is also earlier found in the last four tones of the Largo series)

and which is loosely imitated in its registral contours and cadential

tremolo/pizzicato rallentandi throughout the remainder of the movement.

Significant of the movement’s direction towards new vistas, the final swells

(Example 8d) are to a brilliant and spacious harmonic orientation on G.

Movement I Allegro

To this point a great variety of relationships

to the series have been noted throughout the Quartet, from fairly strict adherence to 12-tone principles, with extra-serial

accompanimental nuances, in thematic expositions, to shifts of particular tones

in particular contexts, the suspension of the twelve-tone context, (often with

a temporary focus on particular series elements), the “intrusion” of series or fragments of series from

one section into the context of another, and the isolation of series elements

or even just key series intervals with free/harmonic intervallic support such

as the “streaming” of thirds or sevenths at various points or the ubiquitous

major seventh with inscribed minor third (0,1,4) trichords. All of these

however are organized in a finely tuned and logical adherence to classical

principles of tonal form: the use of the series to structure thematic statements

and the subsequent fracturing or departure from the series, substitution of

extraneous series or other forms of intervention to structure liquidations or

developmental/contrasting passages, retransitions etc. In the case of the opening Allegro however, where the series is minimally

present and many key tonal elements in the movements to follow are only

suggested in passing, the influence of thematic form and process are most

pervasive and highly developed.

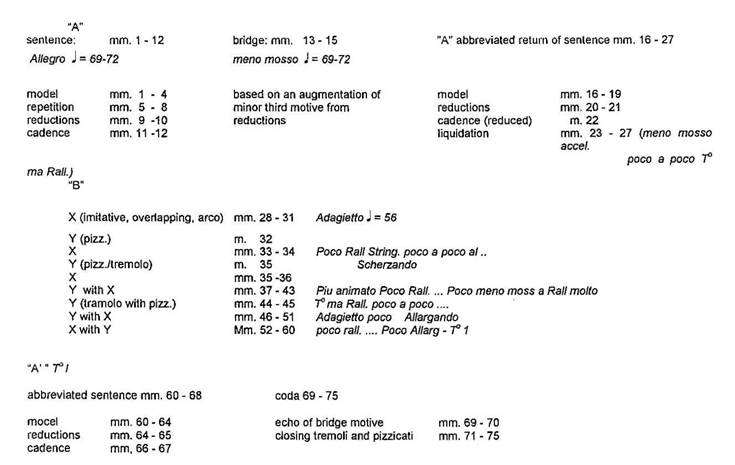

The formal scheme of the movement is given in Figure

1 and the initial sentence structure plus the short bridge can be seen in

Example 9. Correctly speaking, the actual

opening thematic structure would be a short ternary as the sentence returns in

abbreviated form (mm. 16-22) followed by a quick liquidation/transition (mm.

23-27) to a secondary idea and central development (m. 28 onwards).

A number of features emerge in

these opening statements which are clearly integral to the remaining movements

of the quartet. Perhaps foremost is the role of the tremolo as a punctuating

and cadential device in mm. 5 and 12-13. The major thirds E-G# of m. 11 and B-D# of m. 12

are clearly exposed as points of reference; they are repeated in the abbreviated

return of the sentence at the end of the movement but they are significantly

replaced by the ascending third B-D in m. 22 and the end of the short ternary

structure. The motivic structure of mm. 2-4 delineates the first six tones of

the retrograde of the cavatina series in the first violin (E-G-G=-A=-C-E=, also, of course, the first

six tones of the second scherzo series) as well as the minor third cell, B=-D=, which pervades the bridge in

coincidence with the B-D natural. In the shifting motivic focus of the movement

is in many instances flexibly accommodated by aggregate formations (indicated

by -----12-----) which provide a fully chromatic background without the

structuring of a specific series (see mm. 5-6, 9, 10, 11, 12 as in Example 9a

and mm. 29-30 in Example 9b). The opening

motive of the central section (see Example 9b) focuses further on the first

four tones of cavatina 1 series fragment but adds F and A natural to fill out a

chromatic hexachord, which with the complementary chromatic hexachord fills

provides one of the building block of the central development.

The central section initially explores a mixture of foreshadowings

with ideas derived from the chromatic hexachords structures of the secondary

idea (marked “ch.hex/E-A” and “ch.hex/B=-E=”). The reduction

in Figure 2 delineates the registral exchanges of materials as well the

textural developments involving the arco, pizzicato and tremolo sounds qualities.

The first of the 12-tone sign posts to

emerge are the C major/minor triad unfolded in tremolo against the chromatic

motion surrounding the G=-A= major second at m. 42. The referential minor thirds B=-D= and B-D of

the bridge passage emerge in close conflict at m. 47 (note that these four

tones belong exclusively to the B=-E= chromatic hexcachord). The return in m. 51 of the tremolo ideas of m.

43 more clearly reference the

opening series hexachord (A=-G=-G-E - note also that this figure lies exclusively within the E-A chromatic

hexachord) against a high- and extreme-high-register repeated F-A natural

pizzicato tenth, which anticipates the extreme-high-register A natural of the

culmination of the retransition in m. 61 where the opening tremolo sonority of

the movement (B=-G=-A) returns transposed up an octave. Further intricate echoings

of the B=-D=/ B-D opposition arise however, prior to this point in m.

59 and at m. 55-56 where the ‘cello interjects the same A-B oscillation as it does

in the second cavatina.

Example

9:

Ogdon Third String Quartet, First Movement

mm. 1 - 16

Figure

1:

Formal Structure of First Movement

Example 9b: Ogdon

Third String Quartet, First Movement mm.

28 – 32

The

muted coda (mm. 70 -75) follows directly as in m. 17, from the repetition of the

bridge and beginning of the return of the sentence in the pizzicato E=-B-D sonority (see m. 16, note

the D natural is not present in the opening pizzicato) which is repeated in

alternation with its lower whole-tone neighbor (C#-A-C natural) against a sustained

tremolo A= in the viola joined

by the ‘cello in its descending glissando from E to F in a major/minor third

shift suggestive of the A-C to A=-C

at the end of the poco scherzandos and

the Largo. Meanwhile the upper tones of

the D#-B-D pizzicatti delicately foreshadow opening of the series in the following

cavatina.

Commentary

The richness and flexibility

of Ogdon’s Third Quartet appears to

find middle ground between serial

structure and tonal intuition and between Second Viennese/classical form and

phraseology and more recently evolved effects of dissociation and momentary

reference within and across movements. Certain harmonic elements acquire

referential significance over the entire work such as the major/minor triads on

B, C and B= each of which is

linked to 12-tone structures in the first cavatina, first scherzo and second

cavatina. Elements such as the E-G# and A-C# (in the cavatinas and scherzi) and

perhaps even the A=-C natural (in

the poco scherzando and

Figure 2: Harmonic/Textural

Reduction of

Ogdon

Third String Quartet, First Movement mm.

33 – 60. Pizzicato indicated in staccato. “ch.hex/E-A refers

to

the pitches (E,F,F#,G,G#,A) in the chromatic hexachord from E to A and “ch.hex/

Bb-Eb”

to those in chromatic hexachord from Bb to Eb.

retransition,

recalls the B major/minor nuances from the first cavatina and, at the end of the

movement, which recalls of the cadence of the poco scherzando. After the distinct series of the

mov't trem. pizz.

I Allegro F-A= C#-A-C>

to

D#-B-D *

II:

Cavatina I F#-D-F>to D=C

to B=-A

to

E=-F#-D A=-G

to E-E *

Scherzo I E-G-E= G#-B *

Cavatina II E B-B=-A

D-D=-F

Scherzo II E-G-E= B-B= *

Nocturne D-C=-D=-F

Scherzando (non trem.) A=-C to

A-C-C# D-G=-E= *

Trio (non trem.) F-B=-D E G F#

Scherzando (non trem.) C#-A-C D-G=-E= *

III Largo (A>) A=-C A=-G *

IV

Recitativo C#-G#

D-A-E-B

V Andantino F-A-B to G=-A-F G-B-D-F# *

Figure 3:

Closing Pizzicato and Tremolo Sonority Pitches in Each Movement of the Third Quartet

*

indicates tremolo or pizzicato pitches are also the initial pitches of the movement

Beyond the endings of the

movements, the game of reference and development of the arco, pizzicato and tremolo

sonority is active throughout the quartet with a significant absence in the poco scherzando and trio sections of the

second movement and the opening section of the

To finally conclude, it can be observed that

the musical language of Will Ogdon’s Third

Quartet exemplifies the astute patience of many of adherents of the

influence of Leibowtiz, Krenek. and of course, Schoenberg himself. The conception of the series primarily as a

thematic entity within the discourse of classical phraseology and thematic

process is a virtual hallmark of Leibowitz’s teachings [6] and a

concern, which Ogdon has shared in his own teachings - not necessarily or even primarily

for the music of the past, but for issues of tonal intelligibility in its

endless guises and applications. And while

this discussion has taken pains to illustrate what might be considered a

Mozartean thematic elegance, with a Webernian timbral/harmonic and dynamic

sensitivity and even a Beethovenesque sense of interruption, the “personality”

of Ogdon’s music, like that of any of its models, runs clearly much deeper than

this and in its own unique direction.

[1] Note however that this element, the A-B

figures clearly in the twelve tone and extra-twelve tone structurings of the

following Scherzi and the Cavatina 2.

[2] This contrasts with the parallel development

to the E-G# in the first Scherzo of a descending

line and skip.

[3] In the present context this nuance playfully in the trio (m.30) in a momentary A=-C/B=D whole tone alternation in the violins.

[4] The series lacks B= but has, interestingly, two A naturals and two B naturals, the second of which projects the referential B-D at the end of the phrase. The framing repetition of the series is incomplete, leaving off after F natural and closing by repeating A=. Note also that the relation between the violin melody in mm. 9-16 and the series of the second cavatina, the second B= must, in terms of the series, be an altered B natural. The placement of B natural at the end of the initial 12-tone unfolding of the violin melody of the Recitative projects a clear E minor harmonic nuance against the accompaniment at this point.

[5] Note that these elements, the major/minor triads on B=and C plus the major seconds F#/G# and A/B, in addition to any suggestion of the work’s various series, fill out the complete chromatic aggregate in themselves.

[6]

See, for example Leibowitz’s unpublished “Treatise of Twelve-Tone Composition”

as discussed by the present author in

VIII/2 of this journal. It is also

interesting to note, despite Pierre Boulez’s freer phrase structurings in the

early sonatas for piano and the Sonatine, a similar concern for

aggregate completion and series integrity with relation to thematic process and

function. See S. Chang: “Boulez's

"Sonatine" and the Genesis of his Twelve-Tone Practice” (Ann

Arbor, 1998).