Poème du Délire

Bruce

Mather

In

1979 I discussed with Ivan Wyschnegradsky two concert projects, one for the Fragments Symphoniques I, II, III for four pianos

in quarter tones which I realized in January 1980 as a memorial concert (as Wyschnegradsky

had passed away in September. 1979) and the first performance of his three

works in sixths of tones for three pianos, Prélude

et Fugue op 30 (1945), Composition

op.46 No. 1 (1961) and Dialogue

àTrois op.51 (1974). For the concert on April 21st, 1983

two Canadian colleagues wrote new pieces, Aspects

of Jack Behrens and Le

Parcours duJour of John Winiarz and I produced Poème du Délire. The

following year the three Wyschnegradsky works plus those of Behrens and myself

appeared on a vinyl disc of McGill University Records. Among Wyschnegradsky's

manuscripts without opus numbers I discovered years later the Deux Mèditations also for

three pianos in sixth of tones. I conducted the first performance of the work

on May fifteenth, 1996 with pianists Pierrette LePage, Louis Philippe Pelletier

and Paul Helmer.

As

I had used for my quarter tone works the non-octaviant spaces in "régime

onze" (i.e. cycles repeating at a major seventh), I opted for his

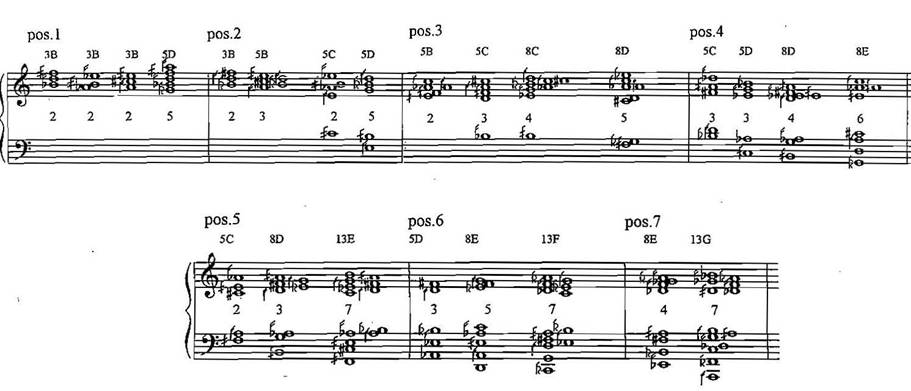

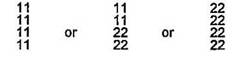

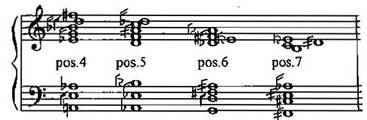

analogous system for sixths of tones. In this system (see Appendix A) the

interval of the major seventh (33 sixths of tones) is divided into three equal

intervals of 11 sixths of tones (one sixth less than a major third). These

notes are in white. Each interval of eleven sixths of tones is subdivided into

three intervals of four, four and three sixths of tones (or 2/3 tone, 2/3 tone,

semitone). For notation in sixths of tones I use only four new signs:

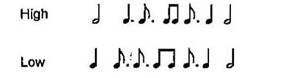

![]() (a sixth tone higher)

(a sixth tone higher)

![]() (two sixths tone higher

(two sixths tone higher

![]() (a sixth tone lower),

(a sixth tone lower),

![]() (two

sixth tones lower).

(two

sixth tones lower).

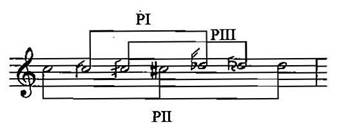

It should be explained that in Poème du Délire (and in

the works of Wyschnegradsky in sixths of tones) Piano I is tuned a sixth of a

tone sharp, Piano II at normal pitch and Piano III a sixth of a tone flat:

Figure 1: Tuning of Three Pianos in Sixth of Tones

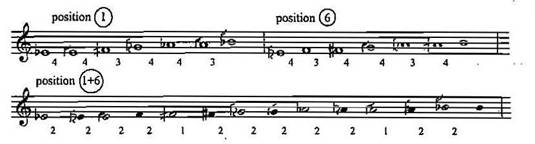

From one

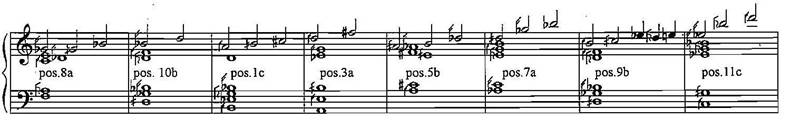

position to the next, in the eleven positions one of the three notes rises a

sixth of a tone. From position 1 to position 2 it is the 'white' note, from

position 2 to 3 it is the first black note and from position 3 to 4 it

is the second black note. The result is that, while in position 1 the division

of each interval of 11 sixths of tones is 4,4,3, in position 2 it is 3,4,4 and

in position 3 it is 4,3,4. In order to obtain smaller melodic intervals (1 or 2

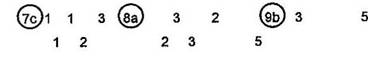

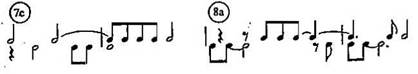

sixths of tones) I combine two positions such as 1 and 6 (Example 2). This

produces many intervals of thirds of tones and some sixths of tones.

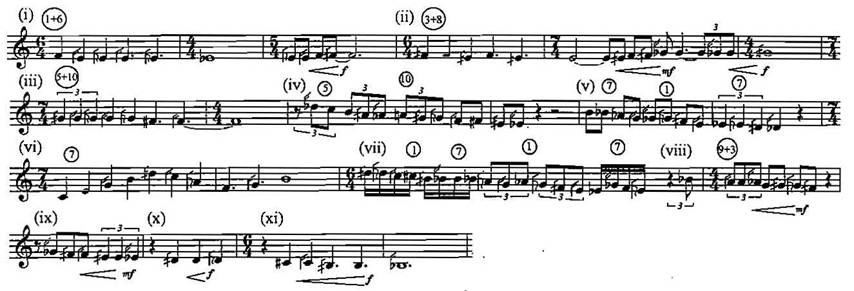

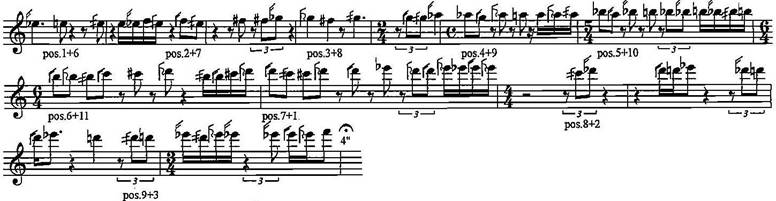

Example 1:

Combination of Positions 1 and 6

Example 2:

Melodic Structure of Section B

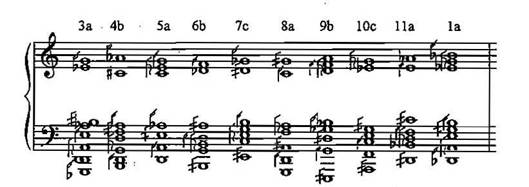

Example 3: Harmonic Structure of Section B

Formally

Poème du Délire

is characterized by the presence of six different elements or textures, most of

which return in a different context, duration or contour. Here are the six

elements:

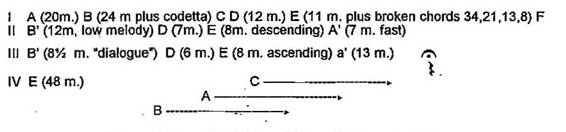

Here

is the large-scale formal plan in four sections, determined by the return of

the elements.

Figure 2: Large-Scale

Formal Plan of Poème du

Délire

It

is interesting to observe the role of each element in the large-scale

structure. "A" starts the work as a long slow monody. It ends the

second and third sections as fast monodies. In the final section it overlaps

with elements "B" and "C". In section I "B"

starts with a higher melody joined soon in dialogue by a lower strand. In

section II it appears, much shorter, with a low melody in fast groups of 2 or 3

notes. In section III the fast groups appear in a dialogue, high and low. In

the final section the fast groups are transformed into element "A".

Element "C" appears in section I and then in section IV, accompanying

the monody "A" and then alone, ending the work. Element "D"

appears in sections I, II, III in progressively shorter versions. Element

"E" appears in sections I, II, III in the same position with durations

of 11, 8 and 8 bars. It begins the final section with a large development of 48

bars. Element "F" appears only once, at the end of section I.

Detailed

Analysis

Section

1 A

As

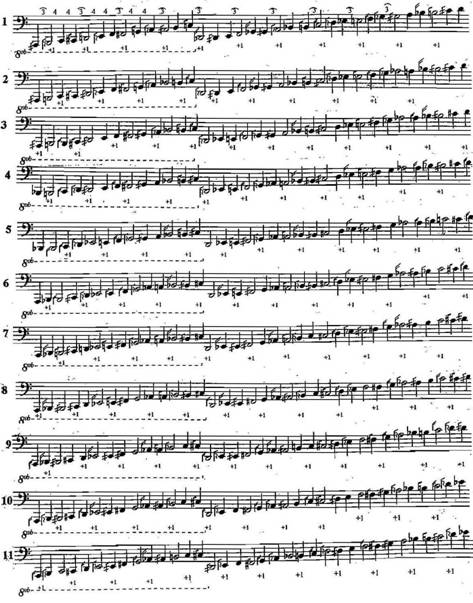

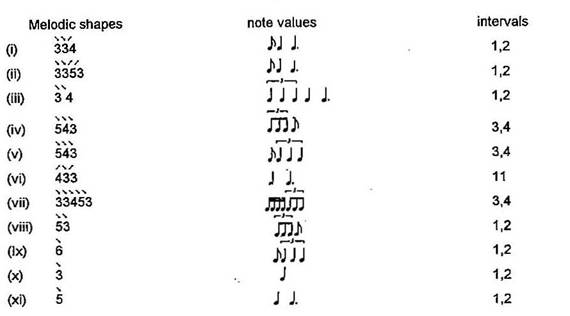

shown in Example 2, the eleven phrases of A use the combine positions 1+6, 3+8,

4+10, 7+1 and 9+3. The scheme below shows the melodic shapes, the note values

used for each phrase, and the intervals used (in sixths of tones). Note the

ritardandos from phrases 4 to 6 and 7 to 11 (see Figure 3).

Section

B Harmonic structure (see Example 3)

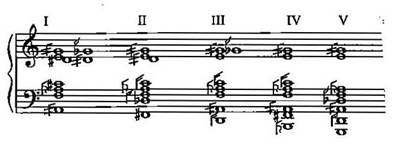

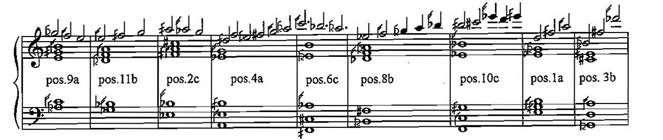

In

each of the 11 positions a white note is followed by 2 black notes. The

intervals (in sixths of tones) are 4,4,3 or 3,4,4 or 4,3,4, always a total of

11 (A sixth tone small than a major third). Chords built from the white notes

carry the letter "a", those built from the first black note

"b", and those built from the second black note "c".

Figure 3: Section B Melodic/Intervallic and Shapes and Rhythmic Values

![]()

Of the

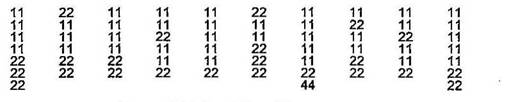

ten chords most have seven notes but three (numbers 1,7,10) have 8 notes. The

top notes of the ten chords are relatively static (from to

![]() ) but the ranges vary from just over

two octaves (chord 3) to over 3 octaves (chord 7). Three intervals are used

11/6, 22/6 and 44/6. As can be seen below only two chords (numbers 4 and 9)

have the same spacing:

) but the ranges vary from just over

two octaves (chord 3) to over 3 octaves (chord 7). Three intervals are used

11/6, 22/6 and 44/6. As can be seen below only two chords (numbers 4 and 9)

have the same spacing:

Figure 4: Section

B Chord Spacings

![]()

Divided

among the three pianos, each piano has two or three notes of each chord (except

for piano I in chord number 8 with only one note). The notes of each

piano are presented in rhythmic ostinatos of 4, 5 or 6 values per half giving,

respectively, eighths, quintuplets of eighths and triplets of eighths. The

patterns of the triplets can be described as 7+(3), i.e. 7 notes in triplets

then 3 in silence etc.

![]() The quintuplet

pattern can be described as 5+(1), i.e. 5 notes in quintuplets plus one in

silence

etc.

The quintuplet

pattern can be described as 5+(1), i.e. 5 notes in quintuplets plus one in

silence

etc.

The

pattern in eighths is less regular as in Piano III p.2 (3+(2), 4+(1), etc.) As

shown below the distribution of the ostinatos between the three pianos changes

constantly:

![]()

Figure 5:

Distribution of Ostinatos Between Piano in Section B

Example 4: Melodic

Strands of Section B

Example 5:

End of Section B

Example 6:

Chord Vocabulary of Chorale:

Section

B Melody

As

shown in Example 4 a high melody (from m.2) is joined by a low melody (m.8).

The two strands then converge. In order to create a rhythmic independence from

the accompanying ostinatos the attacks of the melody are on the second or

fourth sixteenth of the beat. In the first three phrases (over harmonic

structures 4b, 5a, 6b) of 3, 5, and 5 notes, the actual perceived rhythm is h

h h \

q . h q q . h \ q q q h h

.The

dialogue between the two strands starting at m. 8 can be represented thus:

Figure 6a: Representation

of the Dialogue Between Two Strands at M. 8

The high

line descends while the low line rises. The actual perceived rhythm for this

passage is:

Figure 6b: Perceived

Rhythm at M. 8

The

values over chord ![]() are more complex with accelerations 6 , 4, 3,

3, 2 x s

. At chord

are more complex with accelerations 6 , 4, 3,

3, 2 x s

. At chord ![]() the two strands have the same melodic curve

the two strands have the same melodic curve ![]() but

the durations of the first two notes are different. Each line creates an

accelerando - ritardando pattern:

but

the durations of the first two notes are different. Each line creates an

accelerando - ritardando pattern:

Figure 7: Rhythmic Contour in

High and Low Strands

The

phrase over chord ![]() is identical. Over the final chord

is identical. Over the final chord ![]() the eighth-note pulsation returns with a

dialogue similar to that at m. 8:

the eighth-note pulsation returns with a

dialogue similar to that at m. 8:

![]()

Figure 8: Dialogue

of Eight-Note Pulsation in Final Chord of Section B

Example

6 shows the end of the section where the accompanying ostinatos stop, leaving

the convergence of the two parts into a five-note ostinato in x s, then a trill

and a final rising line with ritardando, all in position ![]() .

.

Example 7: Chordal

Development of Chorale

Chorale

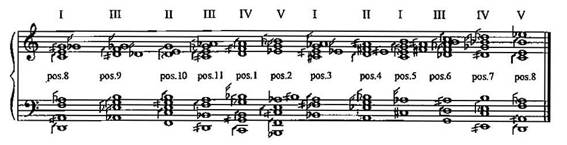

In

general the top notes of the chords of the seven phrases of this chorale

(phrases of 4,4,4,4,3,3,2 chords) describe a slowly descending curve. The

chords increase in density (3,5,8,13 notes, see Example 7). Durations in

quarters are marked below each chord. Example 7 shows the vocabulary of chords

of 3,5,8 and13 notes (all in position 1). The letters describe the range of the

chords C (1 ¼ octaves), D (1 ¾ octaves) E (2 ½ octave), F 2 ¾ octaves), G (4

octaves), B (less than an octave).

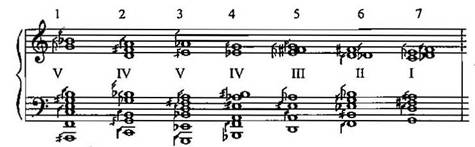

D

This

element is characterized by a melody in sixteenths or triplet eighths

accompanied by chord in quarter, halves or dotted halves. Example 8 shows, in

increasing range, the five-chord formations used: I, II, III, IV, V. Example 9

shows the actual chords and positions.

Example 8: Increasing Range in Section D

Example 9:

Harmonic Structure in D

Figure 9

presents the various rhythmic patterns of the melody and the chords which are

articulated in 2,3 or 4 attacks. There are patterns of 5, 6,7 and 9 beats for

the 12 phrase which contain successively 6,6,7,5,7,5,9,9,5,5,6,6 beats.

Figure 9:

5-, 6-, and 9-Beat Rhythmic Patterns Between Melody and Chords in D

Example 10 shows the first melodic note of

each phrase and its melodic direction (descending, rising descending and then

rising, static). Example 11 shows the first two bars in sixth of tone notation.

Example 10:

Contour Structure in Section D

Example 11: Opening

Measures of Section D

Section

E

The

first section of trill motives marked "leger, envolé: (q = 150) lasts 11

bars. In fact the successive 5-note broken chords of the accompaniment last

6,6,6,10,9,7,7,6,6 beats as shown in Example 12. The five-note chords are

constructed with intervals of 11 and 22 sixths of tones in three different

formats:

Figure 10: Interval

Formats for Construction of 5-Note Chords in E

Example

12 also gives the first note of each trill or chromatic scale motive which

lasts a quarter, half or dotted-half. The motives pass from one piano to

another in the order III, I, II, I, III, II, III, I, II etc. At the beginning

the successive notes of departure are relatively conjunct (intervals of three

and four sixths of tones) but the line becomes more and more mobile. At the end

one has intervals of 11 and 22 sixths of tones.

Example 12:

Opening Succession of 5-Note Chords

in Section E

Example 13:

Harmonic Structure of "Broken Chords" Section

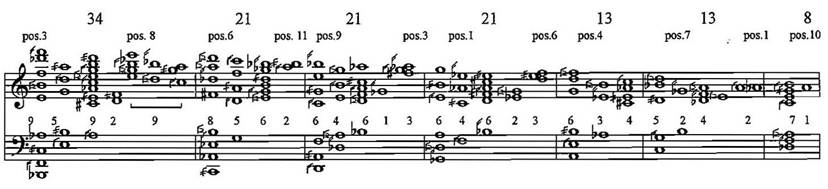

Broken

Chords p. 5 m.5

Following

the first appearance of the trill motives this section acts as a parenthesis.

As shown in Example 13, the seven chords are of 34, 21, 21, 13, 13 8 different

notes following the numbers of the Fibonacci series with a progressively

reduced range and dynamic level. The successive positions used are 3(+8),

6(+11), 9(+3), 1(+6),4, 7(+1),10.

Since

there are only 36 different notes per octave in the scale in sixths of tones

and since I wished to avoid octaves, I was obliged to used the resources of two

positions in many cases (3+8, 6+11, 9+3 etc.) Example 13 shows that the chords

are constructed first with the intervals of 22 and 11 sixth of tones with

smaller intervals in the upper register.

The

chords are broken in various ways. Chords 1,2, and 4 have a fast arpeggio

followed by a solid chord (pp) in the

upper register. Chord 6 is a solid chord (pp). Chord 3 is expressed in triplets

(q

=80), three notes at a time. Chord seven is expressed in 3+2+3 notes and chord

five as single notes in triplet (q =120).

"F"

- Tremolandos pg. 8

Already

at the end of page three (at the end of B) we have a preview of the tremolando.

Exclusively in the high register, this passage is in three parts. The first

consists of tremolando clusters of six notes (two in each piano) rising through

an octave followed by a descending monody.

Example

13 shows the notes from positions 10 and 4 and the actual notes played by each

piano, 5 notes for piano I, eight for piano III and seven for piano III.

Example 15 gives the descending monody in sixth of tones notation and a

"diatonic version" allowing us to see more clearly the melodic curve

in descending groups of 3,2,2,4,2,3 notes.

Example 14: Distribution

of Notes from

Positions 10 and 4 Among the Three Pianos in Section F

Example 15: Descending Monody in Section F

The

second part starts with six note clusters like the first part but this develops

into rapid ostinatos of five and six notes for each piano ending with a rapid

broken chord of 21 notes. It uses positions 2+7. The third part is a

counterpart to the first but with descending clusters and a rising monody. It

uses positions 5+10.

Section

Two

As

already mentioned this section recapitulates some of the elements of section I

with various modifications, the most extremes being A which is now a fast

rather than a slow melody and is placed at the end rather than at the beginning

of the section.

B'

Marked

"mystérieux, menaçant" this passage is only half the length of B in

section I. The seven slowly rising chords of 9 or 10 notes use positions 5a,

6b, 7a, 8a, 8b, 10a, 11a (see Example 10). Instead of broken chord ostinatos

exclusively of 4,5, or 6 notes per half there ar two new arrangements, one

slower (3,4,5) and one faster (5,6,7) as follows:

![]()

The

last chord is articulated ff

with repeated three-note chords in each piano. The melodic element, exclusively

in the low register, is reduced to two or three note "calls in x s (in chords 2 - 6)

moving in third or sixth tones. In Example 16 these are indicated in 'black'

notes.

Example 16: Harmonic Structure in B'

D

p. 10

This passage lasts only seven bars (as

opposed to 12 bars for D in section I). The melodic line is quite static but

descends gradually (except for the last bar which rises to prepare for E). The bar

lengths are 7,5,7,5,6,6,6 q s. Example 17 shows the seven harmonic structures,

at first with a large span (three octaves) then converging to less than two

octaves. The Roman numerals refer to the same chord construction used for D in

section I.

Example 17: Harmonic/Registral

Development of D pg.10

E end of p.

10

The

general curve of this passage is descending. Example 18 shows that the seven

successive structures (built with intervals of 11 and 22 sixth of tones) widens

and then contracts. Example 18 also shows the first note of each trill pattern.

They follow the following descending and rising patterns:

![]()

A'

p.11 m.7

This

rising monody (see Example 19) is developed rhythmically by the filtering of

one six-beat pattern:

Figure 11: Rhythmic Filtering of

6-Beat Patterning in A'

Section

III

The

section has the same elements in the same order as section II, - B' and D being

shorter, A' longer and E the same length.

B'

p. 12

The

four slowly-rising chord structures have 8,9,9,9 notes in positions 1a, 2b, 3c,

4a (see Example 20). The ostinatos create an accelerando as follows:

![]()

Figure 11: Resultant Accelerando From Combination of Chords Structures

in B'

Example 18:

Harmonic/Registral Development of E on pg.10

Example 19: Rising Monody in A' pg.11

Example 20:

Rising Chord Structure of B' on pg. 12

The new

element is the dialogue between low and high two- and three-note

"calls". This can be shown as follows:

![]()

Figure 12: Registral "Dialogue" in B'

In

Example 20 they are shown in 'black' notes.

![]()

![]() D p. 12 m. 10

D p. 12 m. 10

The

melody of this passage starts higher than D of section II and descends

constantly from to . The four chords of eight notes use

positions 4,5,6,7 and decrease in range (see Example 21). Note that the bass

notes descend with small intervals (semitones and 2/3 tones) and the top notes

of the chords with large intervals. The durations of the four chords increase:

5,5,6,9 q s.

Example 21: Registral/Harmonic Development of D on pg. 12

E

p.13 m.3

Contrary

to section II the design here is ascending. The eight basic chords (Example 22)

have durations of 6,4,6,4,6,6,7,7 q s. The melody is in

four rising phrases and chord in two expanding formation (1-4, 5-8) using

positions 8a, 10b, 1c, 3a, 5b, 7a, 9bm 11c.

A'

This

fast monody lasts thirteen bars (as opposed to seven bars before A' of section

II, see Example 23). As in A' in Section it develops through a rhythmic

filtering of the same six-beat pattern (see Figure 13). Sometimes only 2,3,4 or

5 beats of the original pattern are used as a basis for the filtering.

Example 22: Harmonic/Melodic

Development of E on Pg. 13

Example 23:

Monody of A' on pg. 13

Figure 13: Filtering of 6-Beat Pattern in A'

Section

IV

E

p.14 m.9

Example

24 gives the first note of each trill pattern for the six parts of this

passage:

Example 24: Trill Contour of E on pg. 14:

I Each of the four phrases has a descending

and rising curve. The four phrases have 5,5,5,7 notes, each lasting two or

three beats.

II The five phrase

create an almost continuous descent with the following rhythmic pattern: h

h h \ h q q q : \

h h h h h h.

III This part features an alternation of

registers with mostly three-note phrases

![]()

There is an effect of rallentando with only q at the beginning and only h

at the end.

IV The five rising

phrases of 5,5,7,7,5 notes feature only h at the beginning but

introduce more and more q.

V This continuously rising passage is almost

an inversion of II

![]() VI The four phrases

of 5,5,6,3 notes feature mainly large intervals (22 sixths of tones). The

five-note phrase have the same design

: .

VI The four phrases

of 5,5,6,3 notes feature mainly large intervals (22 sixths of tones). The

five-note phrase have the same design

: .

The

third phrase rises in intervals of eleven sixth of tones.

Example

25 shows the harmonic vocabulary of the 5-note accompanying chords with

increasing range (a,b,c,d,e) and variations within each range

(c1,c2,d1,d2,d3,d4).Example 26 gives the accompanying chords for the six parts:

Example 25:

Harmonic Vocabulary in E on Pg. 14

Example 26: Accompanying Chords in E on Pg. 14

Example 27: Coda

Pg.18

Coda

p.18 m.2

In

the final passage the elements B, A and C gradually melt one into the other. As

shown in Example 27 there are five chords of eight notes in converging

registers. These five chord are displayed in ostinatos thus:

![]()

Figure 14:

Ostenato Organization in Coda

After

the third and fourth chords there ar pauses. At this point the two and three-note

"calls" are transformed into a melodic line (element A). Starting at

p. 10 m.6 the element C starts with chord of 5,5,8,13,21,13 and 21 notes.

Between these chords the melody dissolves in motives of 2,3,2 and 3 notes. The

twenty-one-note chord is presented first in two parts (15 high notes then 6 low

notes) and secondly in three parts rising (3+6+12).

Poème du Délire is dedicated to the memory of Alexander

Scriabine (1871-1915) and his disciple Ivan Wyschnegradsky (1893-1979).

Although it stylistically very different from the works of Scriabin, there is

nevertheless a certain influence of the spirit of "Poème de l'Extase"

and "Poème du Feu". In any case both Scriabin and Wyschnegradsky are

composers whose music I treasure deeply.

APPENDIX

A: "Régime

Onze"