Tonal Influences and the Reinterpretation of Classical

Forms in the Twelve‑Note Works of Nikos Skalkottas

Eva

Mantzourani

Norman

Lebrecht's entry in The Companion to 20th Century Music neatly encapsulates

Nikos Skalkottas's image as 'a pupil of Schoenberg, who returned to Athens with

a gospel no‑one wanted to hear, played violin for a pittance and died at

45. Yet, in the 1920s Skalkottas was a promising

young violinist and composer in Berlin, and a student of Schoenberg between

1927 and 1931. It was only after his return to Greece in 1933 that Skalkottas

became an anonymous and obscure figure, who worked in complete isolation until

his death in 1949.

Only recently has his music become more familiar, both in the world of

commercial recordings and in academe.

Yet this isolation from subsequent developments in serialism resulted in the

creation of a highly original twelve‑note compositional style. A

distinctive feature of this style is his method of constructing and evolving

formal designs, which are generated largely through the amalgamation of his

idiomatic twelve‑note technique with his reinterpretation of classical

forms. In this paper I will explore Skalkottas's approach to large‑scale

formal structure, and particularly sonata form, with examples drawn from the

“Ouvertüre” of the First Symphonic Suite (1935) and the Tender Melody

for cello and piano (1949).

As

I have discussed elsewhere,

Skalkottas's most common compositional technique includes the use of a modified

version of the twelve‑note method, the establishment of an analogy

between 'tonal regions' and series as a means to delineate form, and the use of

a motivic developmental technique, similar to Schoenberg's developing

variation,

as part of the motivic organization of his compositions. In his dodecaphonic

works he does not deal exclusively with a single basic set as the binding

element between melody and accompaniment but consistently employs more than one

series. He generally presents them in

groups, each consisting of several discrete series, and usually with a

different group for each major section of a piece. This contributes to the definition of the

harmonic structure by establishing distinct harmonic regions, which largely

delineate the large‑scale form.

Skalkottas conceives these serial groups within a single movement as

contrasting 'keys', each theme being associated with a different group. The

series are closely connected through numerous common and transpositionally or

inversionally related segments, usually trichords and tetrachords. Skalkottas does not exploit the combinatorial

properties of his series, but he uses instead segmental association to connect

logically their presentation within a group. Unlike Schoenberg, however, who

also relies on segmental association to connect two or more forms of the basic

set, Skalkottas uses unordered segments common to two or more different series

of the thematic group. The use of more

than one series as the Grundgestalt of a piece both provides variety

within the unity of the thematic block,

and challenges Skalkottas to move beyond an all‑embracing integration in his

compositions.

Skalkottas's

approach towards both serialism and the construction of forms was very much

influenced by Schoenberg's tonality‑based teaching of the Berlin period,

and his ideas on comprehensibility and coherence. Unlike Schoenberg, however, who allowed tonal

foreground implications back into his later serial compositions, Skalkottas

never abandoned tonal forms of construction and the integration of tonal

elements in his twelve‑note works.

His formal designs emulate those associated with tonal music, such as

sonata, rondo, ternary and theme with variations. Similar to his teacher's approach to form,

which was also influenced by nineteenth‑century attitudes to musical

structure, for Skalkottas such forms are not style dependent, but are approached

as a set of ideal shapes and proportions which can be realized in any of his

chosen styles ‑ tonal, atonal and dodecaphonic, or a mixture of these.

Furthermore, his sonata form in particular is continually challenged and

frequently combined with some other form to produce a complex synthesis of the

two.

The

“Ouvertüre” of the First Symphonic Suite for large orchestra is an example of Skalkottas's approach to

both twelve‑note handling and form.

The piece was composed in 1935, although it was sketched out ‑ the

main themes at least ‑ in Berlin in 1929, possibly under the supervision

of Schoenberg. In the case of this

particular work we are fortunate that Skalkottas left sketchy programme notes,

in both Greek and German, which give some insight into his compositional

strategy. However, it appears that

Skalkottas was not sufficiently careful in his writing, since there are several

inconsistencies and contradictions between his descriptions and the music itself. In these hand‑written notes, which

remain unedited and unpublished, he claims that the “Ouvertüre” 'is written in

sonata form'. He clearly defines it as a

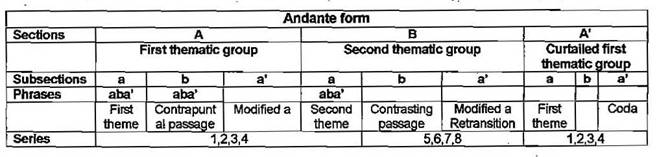

binary structure consisting of two sections, as in Figure 1:

Section A Section B

First theme Second

theme ‑ First theme

Figure 1: Sonata

Form Outline of the Ouvertüre in Skalkottas’ Notes

The

first section conveys the first theme; the second section “starts with the

second theme [¼] is

completely contrasting [...] and is found in great musical opposition to the first

section [...] with a tendency to move towards the preparation of the first

theme,” it also includes a curtailed repetition of

the first theme (section A') and a short coda.

These sections are distinguished from each other by their different

twelve‑note serial content, rhythm, instrumentation, articulation and

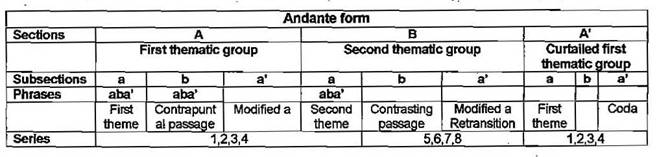

character. However, this formal outline implies either a rounded binary form,

which is the precursor to sonata form, or more likely, an Andante form (ABA'),

which Schoenberg, in the Fundamentals of Musical Composition, groups

with the rondo forms.

Skalkottas

writes in the notes that: “The twelve‑note harmony dominates [¼] and is strictly

connected with the development of the themes', and that 'the first theme

consists of three twelve‑note series.”

However, section A (the “first theme” or more precisely, the “first

thematic group”) (bars 1‑61) is constructed from four, closely connected

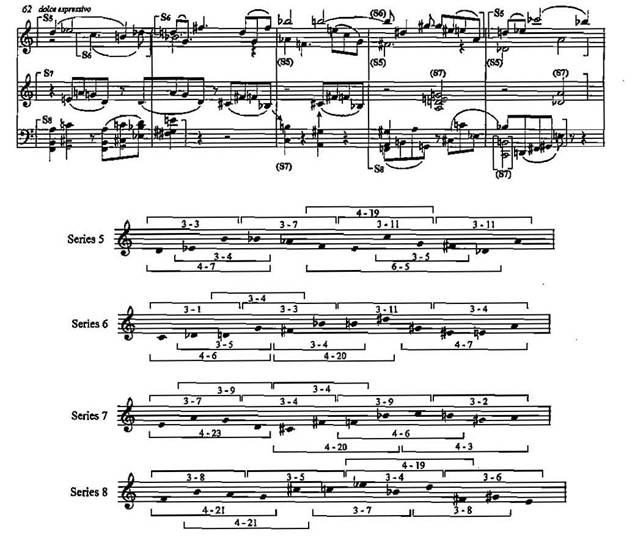

series, used in their prime form only (see Example 1).

In

the foreword to his notes Skalkottas asserts that: “Unlike [other] works

(especially those of diatonic harmony) harmonic transpositions here are

avoided,” thus suggesting that in the Suite harmonic and formal

differentiation are not dependent on transpositions of individual twelve‑note

series and/or entire sections. Instead

he relies heavily on the abrupt sequential presentation of twelve‑note

regions and the manipulation of motivic, rhythmic and textural parameters to

create formal structures. However, in

other works (such as the “Presto” of the Octet, the First Suite

for piano solo, the Third Concerto for piano and ten wind instruments

and the Sonata Concertante for bassoon and piano), Skalkottas does use a

transposition technique in which entire consecutive sections are transposed en

bloc, predominantly at the fifth (although transpositions to the major and

minor third and sixth are also used), thus creating a harmonic movement from a

“tonic” region to another 'dominant' one.

As shown

in Figure 2, which represents schematically the large‑scale serial and

formal structure of the movement, the internal design of section A is

complicated. It consists of three subsections aba', resembling a rounded

binary form. Subsection a (bars 1‑43)

unfolds the first theme, and is also 'ternary' in design (bars 1‑12, 13‑31,

32‑43). The theme in its opening

appearance is characterized by a striking textural contrast between solo

motives and large chords, whose homophonic structure gives a stable and

affirmative quality to the opening of the “Ouvertüre,“ particularly the opening

chord D‑A‑e‑B flat ‑eb1‑gb1 (see

Example 1). This chord provides one of

the most distinctive sounds of the movement, and is used throughout as a

harmonic landmark. It is followed by a

distinct motto‑like melody played by the horns, which Skalkottas claims

“has the character of a signal”; this is used as an aural sign‑post, and

on each reappearance it introduces the three phrases of the theme's ternary

form, at bars 1, 13, and 32.

Example 1:

“Ouvertüre,” Opening Gesture of the First Theme and Series

All the

musical examples from the “Ouvertüre” are presented in reduced form to

facilitate the reading of the serial structure.

Figure 2

Large-Scale Thematic and Serial Structure of the “Ouvertüre”

The

second and third subsections of the first section's ternary form have a

developmental character and a highly contrapuntal texture. Subsection b (bars 44‑53) (see

Example 2), described by Skalkottas as 'a purely contrapuntal section of double

counterpoint', also has a ternary design.

The canonic entries of the motives and the dovetailing of the phrases

maintain momentum and keep the music in a state of flux. Subsection a' (bars 54‑61) is a

brief, modified repetition of the first theme.

Example 2:

“Ouvertüre,” Opening Gesture of Subsection b

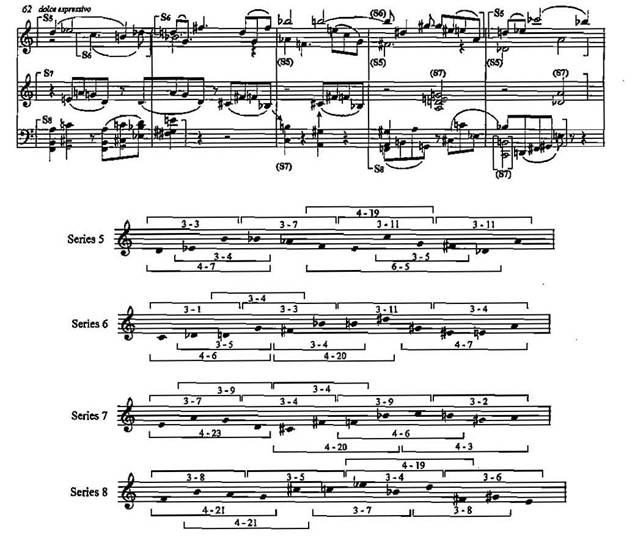

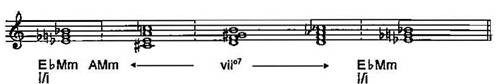

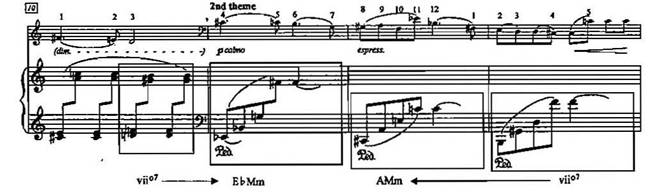

Section

B (the 'second theme' or 'second thematic group') (bars 62‑108), having a

“calm, dolce, espressivo” character, is built on four, new series, shown in

Example 3, thus presenting a new twelve‑note harmonic region.

As

shown in Figure 2, its internal phrase structure also has a rounded binary form

outline aba', similar to that of section A, but its developmental

character contrasts noticeably with the clarity and stability of section A. In

contrast to the first theme the orchestration is essentially soloistic, with

large passages written for small instrumental ensembles, and the texture

tending to thin out at cadences. Subsection a (bars 62‑84) unfolds

the second theme and its varied repetitions.

Subsection b (bars 844‑1001), with

its dense texture, agitated rhythms and the stretto‑like entry of the

motives, is comparable to a contrasting middle section, while subsection a'

(bars 100‑108) provides closure to section B and functions as the

‘retransition' to the recapitulation of the first theme. As with the motivic and phrase structure of

section A, here each of the developmental subsections are introduced with a

varied form of the main thematic idea of the second theme. Section A' (bars 109‑141), introduced

following a long tutti pause, is a curtailed recapitulation of section A. Although the internal phrase structure is

maintained, the subsections are noticeably shorter than their equivalents in

section A. The section ends with a short

coda (bars 142‑148) based on long

six‑note pp and twelve‑note ppp chords, played by the

lower woodwind, brass and strings, which, according to Skalkottas, “emphasize

more the end of the ‘Ouvertüre.”

In

his notes to the Suite Skalkottas states that: “The frequent repetition

of the same harmonic features gives the listener the opportunity to grasp more

easily the musical meaning of the work, both harmonic and thematic.” This

statement reveals his belief in the importance of repetition as the principal

means of achieving coherence and comprehensibility within a movement. In the

complex formal outline of the “Ouvertüre” harmonic cohesion is achieved by

combining certain twelve‑note series and/or their segments (particularly

trichords and tetrachords) to form distinct harmonic units which recur at

regular intervals within the sections. This recurrent succession of different

serial combinations underpins the formal structure and provides coherent

harmonic support to the thematic and motivic development within the movement.

Appendix

I presents an overview of the large‑scale formal, thematic and serial

organization of the “Ouvertüre.” In section A, a short phrase presenting the

opening, antecedent‑like gesture of the main thematic idea, or its varied

repetition, is always based on series 1 and 2, as for example in bars 1‑42,

shown in Example 1. These series are always presented together, with an E flat

minor triad being both the opening and closing gesture of the phrase they

support. This serial combination when

used at the closing phrase of a larger section or at cadential points functions

as a perfect‑like cadence; in Table I it is symbolized as "a".

This is generally followed by another short phrase, in the manner of a

consequent or continuation, based on series 3 and 4, as for example in bars 43‑6

of Example 1. When used at cadential points, this serial combination functions

as a half‑like cadence; it is symbolized as "b" in Table I. In

the middle subsection b of the first theme, passages whose thematic

material is based predominately on series 3 are symbolized as "b1",

while others based on series 4 are represented as "b2". At

developmental passages discrete segments from all four series are juxtaposed in

quick succession or used simultaneously in different formations;

these are represented as "c", "c1", "c2"

and "c3" respectively.

Similarly,

in section B the series are largely employed as pairs 5‑6 and 7‑8. Here, contrary to section A, all four series

are used simultaneously within a phrase.

However, at each reappearance of the group a particular serial

combination predominates by supporting the main thematic or motivic idea of the

passage. The letter "d" represents phrases in which series 5 and 6

predominate or convey the main thematic section, while segments of series 7 and

8 provide the accompaniment. The letter "e" represents phrases in

which series 7 and 8 convey the main motivic lines, while 5 and 6

accompany. As in section A, in

developmental passages discrete segments from all four series are juxtaposed,

combined and used simultaneously; these are represented as "f". In

passages where the variations are so extensive that the motivic ideas related

to particular series are unclear, the serial combinations are stated as "f1",

and "f2". The six‑note and twelve‑note chords

of the coda are shown as "x" and "y" respectively.

Furthermore,

Skalkottas uses segmental association to provide coherent relationships and to

organize the harmonic structure between successive and simultaneous series in

the “Ouvertüre.” All the series are

closely connected through numerous common and transpositionally or

inversionally related segments, while a closely‑knit web of relationships

exists among them, and underpins the entire motivic and harmonic structure of

the movement. As shown in Example 4, in

bars 34‑42 a reordering in the second hexachord of

series 2, bringing the trichord B flat ‑eb1‑gb1 (order

position 10 12 11) before d flat‑a flat –c flat 1 [b] (9 8 7),

and superimposing this segment on G‑c‑f (4 5 6), creates harmonic

conditions similar to those of bars 1‑2: the upper woodwind and upper

strings play an E flat minor triad; the basses accompany with the trichords G‑c‑f

and d flat –a flat –c flat, forming the hexachord set‑class 6‑Z43,

the complement to the opening chord, set‑class 6‑Z17, while the E

flat minor triad has the double function of being both the opening and

cadential chord of the thematic gesture.

Example 3:

“Ouvertüre,” Opening Gesture of the Second Theme and Series

Similarly,

the tetrachords set‑class 4‑18 and 4‑5, included in the four

series, provide a logical continuity in the harmonic‑melodic structure of

the opening theme of the movement. As

shown in Example 4, as a segment of series 1, set‑class 4‑18

initiates the opening gesture of bar 1; in bars 3‑4 it is included in the

cadential chords of the main thematic idea, based on pitch‑class material

from series 2; it appears twice in the closing gesture of the antecedent (bar

6), now a segment of series 3; it also constitutes the opening arpeggiated

figure of the consequent, played by the violin in bar 7. Furthermore, in bar 1 the repetition of the

note g1 within the exposition of the thematic idea (e1‑g1‑d1‑g1) generates the tetrachord

g1‑c#1‑c2‑b1, set‑class

4‑5; in bars 5‑6 transpositionally equivalent forms of this

tetrachord initiate and round off the varied repetition of the thematic motive

in the basses, now based on series 4.

Thus, the initial phrase ends with the harmonic material equivalent to

that with which it began.

At

the closing phrase of section B, the retransition, Skalkottas employs chords

which result from segments that are included in the internal structure of both

themes, thus functioning as modulatory elements leading to the recapitulation

of the first theme.

As

shown in Example 5, in bar 103 the retransition starts with a gesture which is

harmonically supported by the tetrachord D‑A‑e‑g (set‑class

4‑23), played by the basses and cellos, and the chromatic trichord

B flat ‑g#1‑a1 (set‑class 3‑1),

played by the horns, both segments of series 7. The 4‑23 tetrachord,

however, is the same as the first tetrachord of series 2, while the 3‑1

trichord is also included in series 4 of the first theme. In bar 105 the

segment F‑B‑a flat ‑c1 (set‑class 4‑18),

resulting from the combination of segments from series 5, 7 and 8, is also a

segment of series 3. In bars 1064‑1073 the trichord

Db‑Gb‑B flat ,

included in the tetrachord 4‑20 of series 7, is a segment of series 2,

while the tetrachord D flat‑G flat‑b flat‑g#[a flat] (set‑class

4‑22) at bar 1071, resulting from the combination of series 6

and 7, is also a segment of series 2. The trichord eb‑B flat ‑f#1(gb1) (set‑class

3‑11), included in the last tetrachord 4‑19 of series 8 is the same

as the first trichord of series 1; the latter functions as a link with the

recapitulation of section A which starts with the same trichord as part of the

arpeggiated E flat‑B flat1‑E flat1‑G

flat ‑A motive (set‑class 4‑18), played at a lower registral

level by the tuba.

The

inclusion of tonal elements within the twelve‑note texture of the

“Ouvertüre,” particularly the E flat minor triad, although inevitably creating

tension and conflict within the movement, are not form‑generating events.

As mentioned above, the opening chord consists of a superimposition of an E

flat minor triad and the tonally ambiguous quartal trichord D‑A‑E.

Tension is already established from the opening gesture. Taking into

consideration Skalkottas's observation that the piece is in sonata form, it

might be expected that one of the two harmonic areas would predominate and that

there would be some reconciliation at the end. However, there is no harmonic

relaxation or resolution; this is instead provided by the orchestration and the

dynamics. As shown in Example 6, throughout the piece these two sonorities are

superimposed, juxtaposed and define sectional boundaries within the subsection a

of the first thematic area. In subsection b the quartal D‑A‑E chord

predominates, while section A (the first subject area) ends with a sharp

juxtaposition of the D‑A‑E and E flat‑B flat‑G flat

chords. Section B, the second theme, with its contrapuntal texture,

developmental character and harmonic disposition in a state of flux, does not

have a strong tonal center. The recapitulation starts with the same tonal minor‑quartal

sonority and clearly ends with an E flat minor chord at bar 134, the end of the

recapitulation, thus asserting the latter's priority as the “tonic” of the

piece. Typically, however, Skalkottas undermines this event in the coda which

follows, since this is underlined by a sustained pedal of an Eflat minor triad

in second inversion,over an E‑natural in the bass. The final six‑

and twelve‑note chord progression is based on a descending linear voice‑leading

movement to the final D‑A. Thus the harmonic polarization is unresolved

and the harmonic structure of the movement remains open‑ended.

Example 4:

“Ouvertüre,” Section A ‑ Harmonic Structure and Pitch‑class

Associations of the Opening Phrase

Example 5:

“Ouvertüre,” Serial and Harmonic Structure of the Closing Phrase to Section B

Example 6: “Ouvertüre,”

Schematic Harmonic Progression

Overall,

the harmonic movement within the A sections is generally static, and it is

framed by the E flat minor triad in the upper textural stratum and the quartal

D‑A‑E trichord in the lower one. Although there is tension within

the superimposition and sequential juxtaposition of these trichords, there is a

significant lack of meaningful harmonic conflict and polarization, and the

creation of large‑scale tension and resolution which is the

quintessential structural requirement for the traditional sonata form. The mere

juxtaposition of two twelve‑note harmonic regions and, particularly, the

lack of recapitulation of the second theme, suggest that Skalkottas's

description of this “Ouvertüre” as sonata form is inaccurate, and Andante form

more appropriately represents the harmonic and formal procedures applied here.

However,

the Tender Melody for cello and piano does produce harmonic conflict and

a sense of resolution. Tonal elements

are incorporated in the twelve‑note texture, and there

is some tonal movement despite the twelve‑note process. Here Skalkottas

creates a structural form which not only combines two compositional styles,

tonal and serial, but also exemplifies the principles of traditional sonata

form. Furthermore, his fascination with the fusion of traditional forms to

produce new formal structures is again demonstrated through the integration of

three diverse formal prototypes to produce a formal design which amalgamates

variation, sonata and cyclical forms.

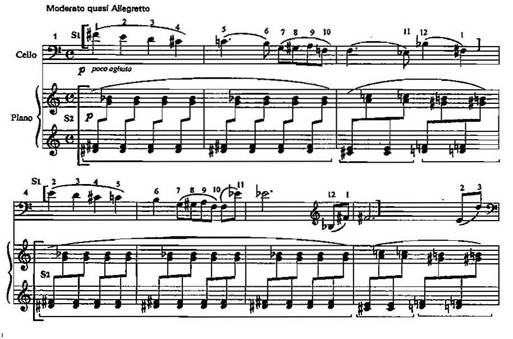

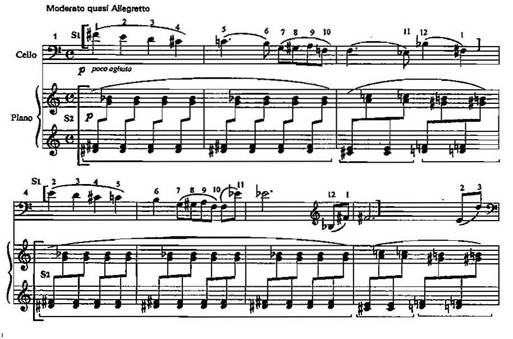

Tender Melody is built on the

prime forms of two independent twelve‑note series, one continuously

played by the cello and the other by the piano, as shown in Example 7. The

Eflat minor context is inherent in the internal pitch‑class structure of

the cello series (F# E D C# C B G G# A F E flat B flat). Within the phrase structure, pitch‑classes

E flat, B flat, and F#(G flat) are grouped together, frequently punctuating

melodic cadences and thus providing a clear orientation towards an E flat minor

tonality. The only exception is found in the last presentation of the series in

the coda, a point to which I will return below. The piano series is presented

as three tetrachords, two transpositionally equivalent (T6) major‑minor

tetrachords, set‑class 4‑17

(D#‑F#‑G‑B flat, C#‑E‑A‑C) and a diminished

seventh tetrachord, set class 4‑28 (D‑F‑G#‑B). It is

worth mentioning that the modal major‑minor tetrachord, set‑class 4‑17,

is an important element of Skalkottas's harmonic vocabulary, and is often used

to frame harmonic progressions, either at the beginning of a passage or as its

concluding destination. This harmonic presentation is unchanged throughout the

piece and the minimalist, almost hypnotic repetition of the tetrachords not

only articulates but reinforces the tonally imbued harmonic framework; it also

leaves the piece open‑ended. When these three tetrachords are heard in

succession they move in smooth stepwise voice‑leading and produce a kind

of functional harmonic progression, from an E flat major/minor chord to its

leading‑note diminished seventh chord; the latter needs resolution to the

“tonic” E flat which immediately follows it (see Example 8).

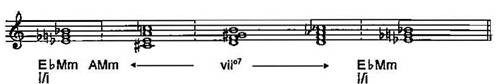

However,

although the A major‑minor tetrachord, in the context of an E flat

tonality, can be perceived as a chromatically altered subdominant chord, it has

a tritonal relationship with the E flat and creates tension within the smooth

voice‑leading, which partially subverts the implied tonal movement.

Furthermore, as shown in Example 8, the tetrachord set‑class 4‑28

can also be interpreted as a diminished seventh on G#, thus functioning both as

the leading‑note chord of the A major‑minor chord and as an axis

within the harmonic progression. Skalkottas exploits the ambiguity in the

interpretation of this diminished seventh chord to distinguish harmonically the

first and second subjects.

The

piece consists of three simultaneous ostinati: melodic in the cello; harmonic

in the piano; and rhythmic, in the form of continuous quaver rhythmic patterns,

in the piano accompaniment. These

underpin the entire texture and constitute the principal structural elements

for unfolding the form. The harmonic

ostinato consists of fourteen statements of the three tetrachords, which

determine the thirteen‑phrase internal structure of the piece. The opening phrase (bars 1‑3), which

outlines the first “theme”, provides all the pitch‑class, harmonic,

rhythmic and thematic material, and functions as the Grundgestalt. Each

of the following twelve phrases presents either a variation of this opening

material, or is a variation within a variation.

These “variations” are grouped together to determine the large‑scale

form of the piece, which outlines six sections, and which can be seen as a

combination of variation form and sonata movement, shown in Figure 3.

Tender Melody Sonata

Movement Thematic Structure

Sections:

I Exposition:

First subject area. First theme (bars 1‑3) and its varied

repetitions.

II Second

subject area: Second theme (bars 11‑13).

III Development:

Elaboration of material form

the first and second subject areas.

IV Recapitulation:

Recapitulation of the second

theme.

V Coda: Recapitulation

of the first theme.

VI Establishment

of E flat minor as the tonic of the piece; final D07 tetrachord.

Figure

3: Tender Melody Sections Sonata Movement Thematic Structure

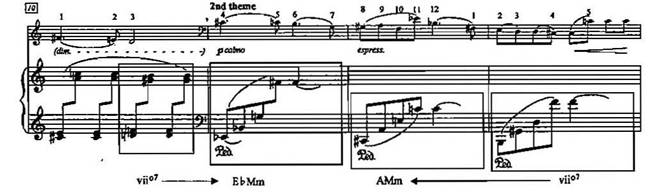

At the

opening three bars both melodic and accompanimental pitch‑class material

coincide. Thereafter there is a misalignment in the melodic and accompanimental

serial structure of the piece. This is resolved in the coda where the cello and

piano series are realigned. The first subject area (bars 1‑10) starts

with an E flat minor chord and ends on a diminished seventh on D; the latter

functions as a dominant needing resolution to the “tonic” E flat. The second

subject area (bars 11‑18) is introduced with a new lyrical theme, a new

texture in the accompaniment, and a different harmonic distribution of the

pitch‑class content of the chords, suggesting a new harmonic environment

(see Example 9).

Example 7: Tender Melody for ‘Cello and Piano,

Opening Gesture of the First Theme and Series

Example 8: Tender Melody for ‘Cello and Piano,

Harmonic Progression

Example 9: Tender

Melody, Opening Gesture of Second Theme

The

cello line starts with a prolonged C# which has a fifth, dominant/tonic‑like

relationship with the opening F# of the first theme.The textual disposition of

the accompaniment now presents the third tetrachord of the progression as a G#

diminished seventh chord, thus shifting the tonal predominance from the E flat

major‑minor chord to the A major‑minor chord.

Bars

19‑36 outline the development section, with bars 31‑36 functioning

as the retransition, which, not only initiates a new rhythmic, quasi modulatory

pattern in the piano accompaniment, but also in traditional sonata-form

fashion, starts and closes with the diminished seventh chord on D, thus

functioning as a dominant preparation and resolving onto the E flat major‑minor

tonic in the recapitulation (see Example 10).

In

traditional sonata form the function of the recapitulation is to resolve the

underlying polarity and harmonic tension established in the exposition, and to

create a sense of reconciliation and closure.

In the exposition of Tender Melody there is inherent tension in

the modal structure of the “tonic” E flat major‑minor chord, and an

expectation for its resolution. There is also harmonic/tonal opposition between

the first and second subject areas, due to the harmonic shift of emphasis from

an E flat major‑minor to an A major‑minor tonal center. As is

typical of Skalkottas's sonata-form structures, the recapitulation (bars 37‑52)

is introduced by the second theme ‑ a typical example of inverted

recapitulation; but harmonic reconciliation is evaded at this point. Although the melodic goal to E flat is

reached at bar 40, with a melodic cadence that outlines an E flat minor arpeggio,

this is supported harmonically by the A major/minor chord, reinforced

throughout this passage by the presence of the G# diminished seventh

tetrachord. Furthermore, the serial

misalignment between the melodic and accompanimental pitch‑class content

continues throughout the recapitulation, thus carrying over and intensifying

further the harmonic tension.

As shown

in Example 11, the first theme, based on a prolonged double pedal Eb‑B FLAT , is

recapitulated at the beginning of the coda (bar 49). At this point the modal ambiguity resolves

with the unequivocal presentation, twice, of an E flat minor triad (the

accented G‑naturals in the piano right hand on the strong beats of bars

50‑51 clearly function as appoggiaturas to F#[G flat], thus further

reinforcing the predominance of the E flat minor color). But the piece does not end at that point; it

ends with the initial succession of the three tetrachords, and the leading‑note,

diminished seventh on note D as the final chord of the piece. Similarly the final gesture of the cello

melody defies structural tonal expectations and outlines the melodic interval e

flat1‑b flat1, heard as an open‑ended, tonic‑dominant

(I‑V) half cadence. Thus, in the coda there is further tension and

openness instead of unequivocal closure Skalkottas (as in Stravinsky's coda of

the first movement of his Symphony in C, and Bartók's piano sonata)

challenges the sonata form he employs.

The piece starts with a stable, albeit tonally ambiguous chord, moves to

a point of rest and resolution at the beginning of the coda but returns to the

unstable diminished seventh chord at its final gesture. Furthermore, the

cyclical, reiterative nature of the harmonic progression throughout the piece,

with the opening of each phrase resolving the previous one and ending itself

unresolved, undermines the sonata principle and renders the form of Tender

Melody circular; there is the impression that the piece could continue

indefinitely. Skalkottas's particular approach to the harmonic structure, which

inevitably affects the large‑scale form of the piece, is reminiscent of,

and perhaps influenced by Romantic attitudes towards ambiguity and open‑endedness

as legitimate formal principles.

Or perhaps the creation of this open‑ended circular form through the

manipulation of the harmony was an attempt on Skalkottas's part to mirror the

circular repeatability of the twelve‑note series and serial groups.

Example

10:

Tender Melody, Retransition Recapitulation

Example

11:

Tender Melody, Recapitulation of first theme and Coda

Paradox

and ambiguity become a structural motive of Tender Melody. Skalkottas

challenges and manipulates the closed unified structure of the sonata form and

its traditional tendency towards unity, by both using cyclical reiterative

harmonic progression and by deferring reconciliation until the coda, and then

denying it at its final gesture. Paradoxically, however, the unstable

diminished seventh chord can be perceived as the only possible close for this

piece. Stylistically, although this is a serial work, it is an exemplar of

tonal serialism, and the manifestation of tonal relationships enables us to

experience harmonic conflict and resolution within a twelve‑note context,

but not final closure.

To

conclude, although there is no record of Skalkottas's views on form, his few

surviving analytical notes and the evidence of his own compositional practice

show that he appropriates traditional concepts of musical construction and

adapts classical formal prototypes to a dodecaphonic context by exploring the

possibilities provided by the integration of different forms and compositional

styles. Skalkottas's amalgamation of his idiomatic twelve‑note technique

with his reinterpretation of traditional forms and stylistic corruption, and

the merging of two styles (tonality and serialism) leads to new and interesting

musical structures, while simultaneously revealing a compositional disjunction

between these traditional forms and the new harmonic language he was

creating. And it is the idiomatic way

that Skalkottas deals with these fundamental compositional issues, and his

attempts to fuse tonal elements of construction with serialism, that ensure his

own particular identity, and his unique contribution to serial

composition.

Table 1: “Ouvertüre”

from the First Symphonic Suite for Large Orchestra:

Schematic

Representation of the Large‑Scale Formal, Thematic and Serial Structure

of the Piece

|

Sections

|

Subsections

|

Bar

Nos.

|

Phrase structure

|

Thematic structure

|

Serial combinations

|

|

A

|

a (1-43)

|

1-42

|

First phrase of the theme's ternary

form.

(Antecedent [1-6]).

|

Motto-like thematic idea in the

horns, based on series 1 (antecedent).

|

a

|

|

|

z

|

43-6

|

|

Varied repetition of the thematic

idea in the basses, based on series 4 (consequent).

|

b

|

|

|

|

7-92

|

(Consequent [7-12]).

|

Varied repetition of the theme in

the first violins, based on series 1.

|

a

|

|

|

|

93-11

|

|

Continuation. Motivic idea based on series 4, similar to

bars 43-6.

|

b

|

|

|

|

114-12

|

|

Closing passage; 'perfect' cadence

to the first phrase of the theme's ternary form.

|

a

|

|

|

|

13-151

|

Second phrase of the theme's ternary

form.

|

Motto-like thematic idea in the

horns, based on series 1.

|

a

|

|

|

|

153-173

|

|

Continuation with predominant

motivic idea based on series 3.

|

c

|

|

|

|

173-231

|

|

Developmental passage introducing new

motivic ideas in two- part counterpoint.

|

c1

|

|

|

|

23-252

|

|

Continuation of developmental

passage.

|

c2

|

|

|

|

252-281

|

|

|

b

|

|

|

|

28-293

|

|

Closing passage to the second phrase

of the theme's ternary form.

|

a

|

|

|

|

293-31

|

|

'Half' cadence to the phrase with

liquidation of motivic and textural material.

|

b

|

|

|

|

32-341

|

Third phrase of the theme's ternary

form.

|

Motto-like thematic ideas in the

horns, based on series 1.

|

a

|

|

|

|

34-37

|

|

Continuation with liquidation of

motivic and textural material.

|

a [b]

|

|

|

|

374-391

|

|

Introduction of the 'rhythmic

episode'.

|

a

|

|

|

|

391-412

|

|

Rhythmic episode which functions as 'half'

cadence to the theme's ternary form.

|

b

|

|

|

|

413-43

|

|

Last appearance of modified thematic

idea in the basses, based on series 1.

Closing gesture to the theme’s ternary form.

|

a

|

|

|

b (44-53)

|

44-46

|

'Contrapuntal section of double

counterpoint'. Contrasting middle

section.

|

Motivic idea, based on series

3, played contrapuntally by

flute-oboes and upper strings.

|

b1

|

|

|

|

46-501

|

|

'Answer' to the previous motivic idea,

based on series 4.

|

b2

|

|

|

|

494-53

|

|

Developmental continuation, leading

to the reappearance of the main thematic idea.

|

c3

|

|

|

a' (54-61)

|

534-55

|

Modified reappearance of the main

theme. Closing phrase of section A.

|

Motto-like thematic idea in the

flutes, oboes, and violas.

|

a

|

|

|

|

56-582

|

|

Continuation with predominant

motivic idea based on series 4, similar to bars 9-11.

|

b+c

|

|

|

|

583-61

|

|

Closing gesture to section A.

|

a+b

|

|

B

|

a (62-84)

|

62-65

|

First phrase of subsection a.

|

Thematic idea, in two-part

counterpoint, based on series 5 and 6.

Series 7 and 8 accompany.

|

d [e]

|

|

|

|

66-701

|

|

Varied repetition of the thematic

idea.

|

d [e]

|

|

|

|

70-72

|

Second, contrasting phrase of

subsection a.

|

Introduction of new motives;

predominant ones based on series 5 and 7.

|

e [d]

|

|

|

|

73-75

|

Third phrase of subsection a.

|

Modified appearance of the thematic

ideas.

|

d [e]

|

|

|

|

76-81

|

|

Developmental continuation,

introducing new motives.

|

f

|

|

|

|

82-84

|

|

Closing passage to subsection a,

introducing textural changes.

|

d [e]

|

|

|

b (844-1001)

|

844-861

|

Contrasting, middle section.

|

Developmental passage, rhythmically

active.

|

d [e]

|

|

|

|

86-87

|

|

Continuation.

|

e [d]

|

|

|

|

88-912

|

|

"

|

d

|

|

|

|

913-931

|

|

"

|

f1

|

|

|

|

932-952

|

|

"

|

f2

|

|

|

|

952-1001

|

|

Fugato cadence to subsection b.

|

d [e]

|

|

|

a' (100-108)

|

100-102

|

Modified repetition of the section's

thematic material.

|

Thematic ideas in oboe-clarinet

(series 6) and trumpets (series 5).

|

d [e]

|

|

|

|

103-108

|

|

Cadential passage to section B with

motivic and textural liquidation, which also functions as transition to

section A'.

|

d [e]

|

|

A'

|

a (109-1293)

|

109-111

|

Modified and shortened

recapitulation of the main thematic material.

|

Motto-like thematic idea in the

tuba, based on series 1.

|

a

|

|

|

|

112-115

|

|

Slow formation of the hallmark

harmony (set-class 6-Z17).

|

a

|

|

|

|

116-119

|

|

Chordal interlude.

|

a

|

|

|

|

120-121

|

|

Repetition of thematic idea based on

series 4 (similar to bars 43-6).

|

b

|

|

|

|

122-1241

|

|

Modified reappearance of

thematic/motivic material of bars 7-9.

|

a

|

|

|

|

124-125

|

|

Repetition of material from bars 94-12.

|

b

|

|

|

|

126-1272

|

|

Cadence similar to that of bars 374-38.

|

a

|

|

|

|

1273-1293

|

|

'Half' cadence similar to that of

bars 39-41.

|

b

|

|

|

b (1293-134)

|

1293-132

|

Contrasting middle section.

|

Motivic idea in the upper strings, based

on series 3; more clearly articulated than in the equivalent passage of

section A.

|

b1

|

|

|

|

133-134

|

|

Motivic idea in the flutes, based on

series 4.

|

b2

|

|

Coda

|

a' (135-148)

|

135-136

|

Last repetition of the main thematic

material.

|

Motto-like thematic idea played solo

by the first violins.

|

a (series 1)

|

|

|

|

137-1391

|

|

Continuation played by the first

violins and violas.

|

b (series 3)

|

|

|

|

139-141

|

|

'Perfect' cadence to subsection a'.

|

a

|

|

|

(142-148)

|

142-144

|

|

Six-note chords.

|

x

|

|

|

|

145-148

|

|

Twelve-note chords.

|

y

|

1 Norman Lebrecht, The

Companion to 20th Century Music (London: Simon and

Schuster Ltd, 1992), 327.

2 For more

details on the composer’s life, see E. Mantzourani, ‘A Biographical Study’ in Nikos

Skalkottas: A Biographical Study and an Investigation of his Twelve-Note

Compositional Processes (PhD dissertation, King’s College,

University of London, 1999). See also,

Mantzourani, ‘Nikos Skalkottas: Sets and Styles in the Octet’, Musical Times,

vol.145/1888 (Autumn, 2004), 73-86.

3 A representative but

by no means extensive sample of recent recordings of Skalkottas’s music would include the

following: 1) Piano Works - BIS-CD-1133/1134; 2) 16 Melodies – Piano

Music - BIS-CD1464; 3) String Quartets No.3 and No.4 (New Hellenic Quartet) - BIS-CD-1074; 4)

Chamber Music (New Hellenic Quartet)

- BIS-CD-1124; 5) Music for Violin and Piano - BIS-CD-1024; 6) Duos with violin

- BIS-CD-1204; 7) Cello Works and Piano Trios - BIS-CD-1224; 8) Concerto

for Two Violins - Works for Wind Instruments and Piano -

BIS-CD-1244; 9) Piano Concerto No.2 (BBC Symphony Orchestra,

Christodoulou) - BIS-SACD-1484; 10) Piano Concerto No.3 - The Gnomes (Caput

Ensemble, Christodoulou) - BIS-SACD-1484; 11) Orchestral works: The Maiden

and Death (ballet suite), Piano Concerto No.1, Ouvertüre Concertante

(Iceland Symphony Orchestra, Christodoulou) – BIS-CD-1014; 12) Orchestral

works: Mayday Spell – A Fairy Drama (Symphonic Suite), Double

Bass Concerto, Three Greek Dances for strings (Iceland Symphony

Orchestra, Christodoulou) - BIS-CD-954; 13) Orchestral works: Violin

Concerto, Largo Sinfonico, 7 Greek Dances for strings (Malmö Symphony

Orchestra, Christodoulou) - BIS-CD-904; 14) Orchestral Works: 36 Greek

Dances (Series I, II, III), Overture for Orchestra ‘The Return of Ulysses,’

Alternative versions of Dances (II/8; II/9; III/6) (BBC Symphony

Orchestra, Christodoulou) - BIS-CD-1333/1334.

4 See Mantzourani, Ibid.; also,

‘The Disciple’s Tale: The Reception and Assimilation of Schoenberg’s

Teachings on Grundgestalt, Coherence and

Comprehensibility by his pupil the composer Nikos Skalkottas’, Journal of

the Arnold Schoenberg Center, vol.3 (2001), 227-238.

5

During

his career Schoenberg’s various definitions of ‘developing variation’ (and its

related terms, theme, motive and Grundgestalt)

were subject to changes of emphasis and nuance.

His essential interpretation, however, as given in his unfinished theoretical

treatise, Zusammenhang, Kontrapunkt, Instrumentation, Formenlehre,

remained constant, and defined developing variation as ‘the method of varying a

motive’, according to which ‘the changes proceed more or less directly toward

the goal of allowing new ideas to arise’ (38-39). For Schoenberg developing variation was

predominantly a motivic process through which a theme was constructed by the

continuous modification of intervallic and/or rhythmic components of an initial

idea; later or contrasting events in a piece, what he calls in his 1950 essay

on Bach in Style and Idea ‘thematic formulations’, could be understood

to be generated from a ‘basic unit’ (397), that is, from changes that were made

in the repetitions of earlier musical

thematic elements. (There are

several important studies dealing with Schoenberg’s ideas of developing

variation. These include Walter Frisch, Brahms

and the Principle of Developing Variation; David Epstein, Beyond Orpheus

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987); Carl Dahlhaus, ‘What is “developing

variation”?’, in Schoenberg and the New Music, (trans) Derrick Puffet

and Alfred Clayton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 128-133; and

Ethan Haimo, ‘Developing Variation and Schoenberg’s Serial Music’, in Music

Analysis, 16/iii (1997), 349-365.

Schoenberg’s own valuable thoughts on motive and developing variation

can be found in Fundamentals of Musical Composition, (eds) Gerald

Strang and Leonard Stein (London: Faber and Faber, 1990); in several essays in Style

and Idea, (ed.) Leonard Stein, (trans.) Leo Black (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1984); in the Gedanke manuscript (see Alexander Goehr,

‘Schoenberg’s Gedanke Manuscript’ in Journal of Arnold Schoenberg

Institute, 2/1 (1977), pp.4-25); in Zusammenhang, Kontrapunkt,

Instrumentation, Formenlehre (ZKIF), (ed.) Severine Neff, (trans)

Charlotte M. Cross and Severine Neff (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press,

1994); and in The Musical Idea and the Logic, Technique and the Art of its

Presentation, (eds and trans) Patricia Carpenter and Severine Neff (New

York: Columbia University Press, 1995)).

Although Schoenberg’s frequent references to developing variation are

found in essays written after his time in Berlin, there seems little doubt that

Skalkottas would have been aware of his teacher’s thoughts on motive,

development, comprehensibility and coherence, and that developing variation was

an essential technique for both the classical composers and Schoenberg

himself. His approach, however, is not

identical to Schoenberg’s, since the latter regarded developing variation as a

process evolving primarily within a given melodic line (although Frisch has

shown that the accompaniment was occasionally involved in the process; see, Brahms

and the Principle of Developing Variation, 17). By contrast, Skalkottas does not deal

exclusively with one melody, or one basic motive from which other motive-forms

are derived and subsequently developed.

Instead, he derives all the elements for his development from both the linear

and vertical dimensions of the thematic block.

Each of the melodic lines is developed individually during the course of

a movement, acquiring thematic status at some point, and becoming a source of

new motivic material. His developmental

motivic process, therefore, inevitably does not apply exclusively to a

principal melodic line, but it does involve the interaction between lines.

6 There are only a few

references to Grundgestalt in Schoenberg’s writings. In such cases he appears to use the

term as a synonym for basic set, tone-row or note-series in twelve-note music

(see for example, Schoenberg, ‘My Evolution’, The Musical Quarterly,

38/4 (Oct. 1952), 517-527, 527; also Structural Functions of Harmony

(New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1969), 193-194). However, Joseph Rufer

and Erwin Stein, based upon their studies with Schoenberg in the early 1920s,

assert that he used the term as a broad musical concept, applying to all types

of music, as ‘the musical shape which is the basis of a work and is “its first

creative thought”’; in twelve-note works, in particular, the Grundreihe

(basic set) is derived from the Grundgestalt (see Joseph Rufer, Composition

with Twelve Notes Related Only to One Another, (trans.) Humphrey Searle

(London: Barrie and Rockliff, 1969), vi-viii; see also Stein, ‘New Formal

Principles’ in Orpheus in New Guises (London: Rockliff, 1953), 62; and

David Epstein, Beyond Orpheus, 17-33).

In Skalkottas’s case Grundgestalt denotes the basic compositional

material, which is presented as a complex basic shape, consisting of several

series in the form of distinct and independent melodic lines, thus becoming the

generative source of the movement.

Within a given piece, therefore, everything becomes ‘motivic’ in the

sense that all of the material of a movement is derived from the same basic

source, which here is the twelve-note serial complex.

7 For a

similar discussion on Schoenberg’s approach to form, see Charles Rosen, Schoenberg

(London: Fontana Press, 1976), 96.

8 The First Symphonic Suite is in six movements: Ouvertüre,

Thema con Variazioni, Marsch, Romance, Siciliano-Barcarole, Rondo-Finale.

9 Skalkottas, ‘Notes

to the Ouvertüre’ (unpublished MS).

Henceforth all quotations taken from these notes appear in quotations

without further citation. Skalkottas, ‘Notes to the Ouvertüre’ (unpub-lished MS). Henceforth all quotations taken from these

Notes appear in italics without further citation.

10 Schoenberg, Fundamentals

of Musical Composition, 190.

11 Examples of this can be seen in Chopin’s Prelude Op.28 No.23 in F major,

whose final V7 in B FLAT encapsulates these Romantic attitudes towards the final chord of a

movement, or in Schumann’s ‘Im wunderschönen Monat Mai’ from Dichterliebe,

Op.48, a typical example of circular form, which starts with a traditionally

unstable V7 chord of F# minor, moves to a point of rest with a

stable, perfect cadence in the relative A major in the middle of the piece, and

ends on a V7 of F# minor, which needs resolution, so that the form

becomes infinitely repeatable (for further discussion about the form of this

song, see Rosen, The Romantic Generation (London: Fontana Press,

1996), 48).