“Rejoicing Discovery”

Revisited: Re-accentuation in Russian Folklore and Stravinsky’s Music

Marina Lupishko

To Valeriya Fyodorovna Kravets, my first Russian music Teacher (1940-2007)

They [the members of Camerata] advised me to assimilate the manner praised by Plato and

other philosophers who claim that music is nothing but word,

then rhythm, and finally sound but not the other way

around.

(Giulio Caccini, Le nuove musiche, 1601, cit. in

Vasina-Grossman 1972: 60-1).

Igor Stravinsky is known to have

assimilated precisely those traits of Russian folklore that later became the

elements of his own mature style – a lack of formal and motivic development,

harmonic ambiguity, and rhythmic and metric unpredictability. As a pre-eminent

reformer of rhythm Stravinsky has been addressed in numerous studies in English

and other European languages (White 1979, Lindlar 1982, Van den Toorn 1983, Vlad 1985, Walsh 1988, etc.). Although all

these authors are aware of the folk origins of Stravinsky’s musical language,

most of them, however, pay little attention to the fact, self-evident for a

Russian researcher, that Stravinsky’s rhythmic innovations resulted to a great

extent from his exploration of the rhythmic peculiarities of his native

language, particularly the language of Russian peasant poetry.

Since

the pioneering studies of Asafiev and Belyaev were made in the 1920s and

subsequently translated into English (Asafiev 1977, 1982; Belyaev 1928, 1972),

many Soviet musicologists have touched upon the subject of Stravinsky and

folklore (Birkan 1966, 1971; Vershinina 1967; Yarustovsky 1982; Grigoriyeva

1969; Kholopova 1971; Alexandrov 1976; Meyen 1978; Golovinsky 1981,[1]

1985; Druskin 1979; Paisov 1973, 1985; Kon 1992, etc.). With the exception of

Yarustovsky (Jarustowsky) 1966, Kholopova 1974, and Druskin 1983, these works

have not been translated into European languages and thus are almost unknown to

the western reader.[2]

Yet for the purpose of conciseness I shall discuss here only four authors whose

works served as the main inspiration for the present study: two Americans,

Richard Taruskin and James Bailey, and two Russians, Valentina Kholopova and Miron

Kharlap.

Taruskin was the one who literally

“opened the door” to the mystery of Stravinsky’s prosody in his 1987 article

entitled “Stravinsky’s ‘Rejoicing Discovery’ and What It Meant: In Defense of

His Notorious Text Setting.” This article later entered as a constituent part

into the two-volume Stravinsky and the

Russian Traditions: A Biography of the Works through Mavra (Taruskin 1996),

where for the first time the folk sources of Stravinsky’s texts and music are

studied systematically. Kholopova, although not concerning herself directly

with Stravinsky’s text setting, can be credited with initiating discussion of

the interaction of poetic and musical rhythms in Russian art music in her 1978

article subtitled “Russian musical dactyls and pentasyllabic meters.” Drawing

on Asafiev’s theory of intonation and on the related works of contemporary

philologists and linguists (Shtokmar 1952, Propp 1961, Zhirmunsky 1975, etc.),

this analytical study substantiates the existence of the typically “Russian

musical meters” borrowed from literary and folk verse in the works of almost

all major Russian composers of the 19th century. The article was later

published in its expanded version, covering all periods of Russian music

history, as Russian musical rhythm

(Kholopova 1983). Unfortunately, neither Taruskin’s groundbreaking piece of

research, nor Kholopova’s interesting metric studies have ever been translated

into each other’s languages.[3]

The other two authors, Bailey and

Kharlap, are both linguists by profession who had a musical education as well.

A student and follower of Roman Jakobson and Kirill Taranovsky, Bailey had

devoted over twenty years to the study of Russian lyric folk verse before publishing in 1993 Three Russian Lyric Folk Song Meters, a much-needed study since

exclusively Russian epic folk verse

had been thoroughly researched by his predecessors.[4]

The preparatory and parallel work to this opus in the form of twelve landmark

articles has been recently translated into Russian and published in Moscow

under the title Selected papers on

Russian folk verse (2001). Finally, the Soviet musicologist-linguist

Kharlap (d. 1991) is the author of, among many other things, the 1972 article

entitled “Russian folk barring system and the problem of music’s origin.” This

very original interdisciplinary study uses a holistic approach to the problem

of the irregular metric scheme of Russian folk verse cum music, exploring the link between the poetic and the musical

rhythm, as well as between the rhythm and the melody of Russian folk song.

And yet, the main incentive to this

project was the discrepancy between the approaches of the two American

researchers, Bailey and Taruskin, to the very controversial topic of the re-accentuation

(shifting stress) of Russian folk verse. Taruskin (1996: 1207) sides with the

late Stravinsky (Expo: 121) that the

shifting stress of Russian folklore is caused by the distortion of the literary

accents of the verse by means of music, while Bailey (1993: 15) explains that

the phenomenon is brought about by the necessity to adapt the stress-flexible

language of Russian folk poetry to the specific folk poetic meters. In the 1993

monograph, Bailey concerns himself in particular with pesennïe metrï (lyric folksong meters); however, his findings can

be applied to a number of genres of Russian folk verse – spoken and sung,

ancient and recent.

At the same time, it would be a

mistake to suggest that the folk re-accentuation occurs only because of the

verbal rhythm. It is an established fact that in the folksong collections of

Tchaikovsky, Lyadov, and Rimsky-Korsakov, to which Stravinsky was exposed early

in his life (Mem: 97), the accents of

the spoken verse are often distorted to a greater or lesser extent in the

music.[5]

Thus the problem under consideration becomes a very complex interdisciplinary

puzzle that needs to be disentangled from both ends, linguistic and musical.

The title of this paper points to

several directions at once: those of vocal music theory, prosody and phonology

of the Russian language, Russian literary and folk versification, Russian

ethnomusicology, etc. Some of the topics addressed here have been clarified,

others have been raised and still await an answer, yet many others have been

passed over in silence almost entirely. Intended more as a methodological

glossary than as a catechism, this paper will try to resolve only the most

essential of them. Several specific cases of re-accentuation in Stravinsky’s Russian

vocal music of the early Swiss period (1913-17)[6]

that have parallels in Russian folklore will be discussed briefly at the end.

Vocal Music versus

Poetry

As is well known, everyday speech in

any language has at least two common grounds with music: rhythm and intonation.

Poetry (that is, metrically organized poetry and not vers

libre) has at least one additional parameter

in common with music – that of meter.[7]

The problem of transformation of poetry by way of music leads to the question of

correspondence between poetic feet and musical measures, the two smallest units

of these two very different metric systems (Monelle 1989). It needs to be

specified right away that the present study will examine solely Russian

versification in relation to the western European measure system – the two

“main ingredients” of Stravinsky’s vocal works of the Swiss period.

“[It is a] well-known fact that

Russian verse allows the tonic accent only” (Chron: 78). Stravinsky’s statement is true in general: Russian

poetry is qualitative and not quantitative, that is to say, accentuation is

achieved predominantly by the placement of expiratory accent (accent tonique in French) and not by the durational ratios between

long and short vowels. To be more precise, Russian classical poetic meters are

frequently referred to as “syllabo-tonic meters,” i.e., both the number and

position of accents and the number of

syllables per line are significant. Roughly speaking, Russian literary verse is

made up of a constant number of uniform poetic feet, either two-syllable ones

(trochee Sw, iamb wS), or three-syllable ones (dactyl Sww, amphibrach wSw,

anapest wwS).[8]

It is obvious that only trochees and dactyls can be directly “translated” into

music as two-beat (2/4) and three-beat (3/4) measures, while other poetic

meters will have the appearance of over-the-measure rhythmic motives, either

with a one-beat anacrusis (iamb, amphibrach) or with a two-beat anacrusis

(anapest).

On the

other hand, music possesses a quantitative aspect, not characteristic of

Russian or western European versification. In western European music, the basic

metric components are conventionally in a strict double or triple durational

ratio to each other, although more complex ratios are also possible. Because of

this aspect, there exist numerous ways of musical transformation of, let us

say, a simple trochaic foot: qualitative (metrically fore-stressed),

quantitative (prolonged first syllable), with a dotted-note rhythm, syncopated,

in augmentation, diminution, or any combination thereof.[9]

On the whole, the poetic meters with three-syllable feet – dactyls,

amphibrachs, and anapests – generally have fewer possibilities for musical

transformation than those with two-syllable feet (Ruch’yevskaya 1966: 82).[10]

This happens because in two-syllable meters even ictuses are accented sometimes

stronger or weaker than odd ones – in the same way as there are strong and

relatively strong beats in the musical meter 4/4. This phenomenon (called

“accentual dissimilation” – see below) is not very typical for ternary poetic

meters, usually represented as 3/4, where ictuses are usually fulfilled by a

stress in the rhythm.

In comparison with music, which is

governed by a complex system of metric, rhythmic, dynamic accents, etc., there

are only two different kinds of accents in poetry – word accents and phrasal

accents. Word accents are considered metrical when they correspond to an ictus

in the poetic meter, and non-metrical when they do not. Consider this famous

line from Lermontov:

Meter Rhythm

Белеет

парус

одинокий[11]

Beléyet párus odinókiy wS wS wS wSw wS wS ww

wSw

The poetic meter of this line is a four-foot

iamb (iambic tetrameter) with a feminine ending. Here the word accents coincide

with the ictuses in all instances but one: the first “o-” in “odinókiy.” The

rhythm of the poem is different from its meter because the ictus corresponding

to the first syllable in “odinókiy” does not receive a stress in the rhythm.[12]

Compare now with a line from Nekrasov:

Meter

and Rhythm

Однажды в

студёную

зимнюю пору[13]

Odnázhdï v

studyónuyu zímnyuyu póru wSw wSw wSw wSw

This is a

four-foot amphibrach (amphibrachic tetrameter) with a feminine ending. Here all

the ictuses are fulfilled because they coincide with the word accents, and thus

the rhythm and meter of the poem are in perfect correspondence with each other.

In contrast to poetry where some ictuses can be perceived as virtual (being

unfulfilled in the rhythm), in vocal music all ictuses are always perceived as

real (being fulfilled in the rhythm). The general slowing down of the text of

vocal music as compared to the spoken verse (with the exception of musical

patter) can sometimes undermine or even destroy the regularity of the poetic

meter. On the other hand, total correspondence between two- and particularly

three-beat musical measures and two- and three-syllable poetic feet over an extended

period of time quickly leads to an unbearable monotony in vocal music,

especially in a slow tempo (Ruch’yevskaya 1966: 82-3).

In the literary Russian language,

word accent can fall on any syllable of a word, and there are usually no variants

in accentuation of one and the same word (case changes notwithstanding),

although Russian literary accentuation has changed considerably over the last

two centuries. Correct word accents are as important in Russian as in English,

and their non-observance can lead to a total change in meaning, as, for

instance, in “zámok” (castle) and “zamók” (lock). Correct literary accentuation

distinguishes a Russian native speaker from a foreigner, an educated person

from an uneducated one, and a resident of the capital from a dialect-speaker.

In vocal music, there exists a method of correlation between musical and poetic

metric accents, the so-called “rule of prosody,” allowing for better

understanding of the text on the part of the listener. The unwritten rule states

that ictuses in poetry should always fall on strong or relatively strong beats

in music. However, a too strict observance of this rule can be tedious because

the temporal aspect is of much greater importance in music than in poetry. For

this and other reasons (many of them are yet to be found), in all European

vocal music – ancient and modern, classical and popular, small-scale and

operatic – an occasional shift of the

correct accent is not only permissible but sometimes desirable and even

unavoidable.

Russian Folk Song

versus Russian Folk Verse

Stravinsky was not the first Russian

composer to write vocal works, nor was he the only one to become interested in

the theoretical possibilities of bringing out the essence of Russian language

by way of music. As Kholopova argues in her article (1978: 164), the problem of

approach to the study of “Russian musical rhythm” is one of methodology, and

the methods are suggested by the historic conditions of the development of

Russian professional music over the previous two centuries. One of them is the

conscious exploration by virtually all 19th-century Russian composers of the

link between music and word – i.e., between musical rhythm and common speech,

folk and literary verse, etc. – as a way to ensure the creation of a truly

national art, which explains the increased attention these composers always

paid to vocal music. From Dargomyzhsky’s credo (“I want [musical] sound to

directly reflect word”), through Balakirev’s declaration of the direct dependence

of music upon word, to the metrically complex Lieder of Borodin, the picturesque recitatives of Musorgsky, and

the compound speech-like meters of Rimsky-Korsakov, the realm of Russian

language historically served as an impulse for the most daring musical

innovations. According to Kholopova, these and other composers relied heavily

on verse theory in their attempts to describe the peculiar rhythmic qualities

of their music (1978: 165). Numerous parallels appeared – those between poetic

feet patterns and specific musical rhythmic formulae, between metric structures

of verses and measure groupings, between the rule of alternance[14]

in poetry and its realization in music, and so on (1978: 166).

The specifically folk Russian rhythmic formulae, also

prominent in Russian literary poetry imitative of folk verse – final dactyls

and pyatislozhniki (pentasyllabic

meters) – are studied thoroughly by Kholopova (1978: 185-228), who finds them

in vocal and instrumental works of all the significant Russian composers of the

19th century. Both formulae have their origin in the following Russian lyric

folksong meters, tentatively presented in a chronological order by Bailey

(1993) – from the archaic trochaic tetrameter to a more recent two-stress tonic

verse:[15]

1) SwSw SwSww Trochaic

tetrameter with dactylic endings:

Отставала

лебедь белая Otstavála

lébed’ bélaya (Bailey 2001: 112)

Как

от стада

лебединого[16]

Kak ot stáda lebedínogo

2) wwSww wwSww

5+5

meter with a caesura in the middle:

Я вечор млада во пиру была, Ya vechór mladá vo pirú bïlá, (Ibid.: 213)

Во

пиру была, во

беседушке[17]

Vo pirú bïlá, vo besédushke

3) wwSwww wwSww Two-stress

tonic verse with dactylic endings:

wwSwwwww wwSww

Я

вечор молода

во пиру была, Ya

vechór molodá vo pirú bïlá, (Ibid.: 213)

Во

пиру была

пирочке, во

беседушке[18]

Vo

pirú bïlá piróchke, vo besédushke

What pushed Bailey into his exploration

was the insufficiently known Russian lyric folk verse, on the one hand, and the

rejection by virtually all verse theorists of the 19th and 20th centuries of

the existence of any repeated classical poetic meters in Russian folk verse, on

the other hand. Perhaps one reason for this rejection was the habit of linking

all classical poetic meters to western European literary versification. This

very popular contraposition of Russian and non-Russian ways of cultural

development also implied that Russian folk verse had nothing in common with

Russian literary poetry, heavily influenced by western European models (Bailey

2001: 63). Using numerous (in fact, many thousands) examples of folk song

texts, Bailey refutes this theory. The author demonstrates not only that

regular poetic meters are better preserved in lyric verse than in epic verse

(Ibid.: 215), but also that trochees are widespread in various traditional

genres of Russian folk song texts (bïlinas,

historic songs, funeral laments, ballades, wedding and love songs, etc.). This

proves to some extent that the folk trochaic meters are more ancient than the

irregular two- and three-stress tonic verse patterns, previously considered as the most typical of Russian folk poetry.

In fact, all the three poetic meters

are variants of each other, for the phenomenon of “accentual dissimilation,”

present in the trochaic tetrameter (Bailey 2001: 43), stands for the fact that in Russian folk verses even ictuses are

often accented stronger than odd ones (as in the trochaic tetrameter with

dactylic endings “Otstavála lébed’ bélaya”) – hence the difference between S

and S on the scheme above. Therefore, one can roughly speak of the following

three common features of these meters: (1) the initial anapest wwS, (2)

the final dactyl Sww, and (3) the two-stress tonic verse pattern with a

variable number of syllables per line wwS…Sww. The dactylic

ending is recognized by many Slavists beginning from Tred’yakovsky (1752) as

the most stable and typically Russian folk element, found both in lyric and

epic folk verses. On the other hand, the initial anapest in Russian folk poetry

is found to be frequent but not constant (Bailey 2001: 334).

The combination

“initial anapest + dactylic ending” produces a centrally stressed five-syllable

formula, very typical of Russian lyric folk poetry: wwSww. The

expressions “krasna dévitsa” (lovely girl), “dobrïy

mólodets” (fine fellow), “chudo chúdnoe” (wonderful wonder), “divo dívnoe”

(miraculous miracle), “okeán-more” (ocean-sea), and the essential “ya lyublyú

tebya” (I love you) are all cases in point.[19] The abundance of

such pentasyllabic idioms supports the presence of a caesura (metric pause)

between the two hemistiches of the 5+5 meter. Sometimes folk singers insert the

particle “da” in place of the caesura (note the typical folk accent in

“lyúdi”):

Все люди

живут – как

цветы

цветут,

А моя

глава да

вянет как

трава.[20]

Vse lyudI zhivút – kak tsvetï tsvetút, wwSww wwSww

A

moyá glavá da vyánet kak travá. wwSww (w) wwSww

These instances do not ruin the basic

5+5 meter (Bailey 2001: 83). The ten-syllable poetic line is the basic metric unit

here because major syntactic articulations come at the end of even hemistiches.

Interestingly, the phenomenon of “accentual dissimilation” is also present to

some extent in the 5+5 meter, if the caesura between the two hemistiches is

taken into account as a substitution for a weak syllable. As Bailey proves by

his statistical analysis, the third and eighth syllables are constantly

stressed, and the first, fifth, sixth, and tenth syllables reveal a tendency to

be stressed – SwSwS SwSwS (Ibid.: 85).

As Kholopova demonstrates, folk

pentasyllabic meters were appropriated by several major 19th-century Russian

poets, notably Lermontov, Kol’tsov, and Nekrasov, and transformed by

professional composers directly into the 5/4 musical meters found in Glinka,

Balakirev, Borodin, Musorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Arensky, Tchaikovsky, Lyadov,

Glazunov, Scriabin, etc. (Kholopova 1978: 204-228). Paradoxically, in Russian

genuine folk music this five-syllable formula is often extended to fit a six-beat musical measure by doubling the

rhythmic value corresponding to the third or the fifth syllable of each

hemistich (Popova 1955I, cited by Kholopova 1978: 182). The beginning of the bïlina “Kak vo gorode stol’no-Kievskom,”

cited by Kholopova on p. 181, serves as an example of lengthening the fifth

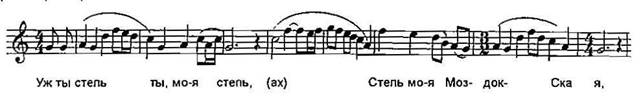

syllable of each hemistich of the 5+5 meter (see Example 1):

Как во городе стольно-Киевском

Kak vo górode stol’no-Kíevskom wwSww wwSww

У Владимира Красна Солнышка[21] U Vladímira Krasna

Sólnïshka wwSww wwSww

Example 1: Bïlina "Kak vo gorode stol’no-Kievskom"

(Kholopova 1978: 181)

On the other hand, musical five-beat

meters are also present in Russian folk song but achieved in a different way:

usually by adding melismas to the trochaic tetrameter (Kholopova 1978: 183; no

example is given). Cases of melismatic lengthening of the trochaic tetrameter

and other folk poetic meters in the melody of the slow lyric drawn-out song (protyazhnaya pesnya) are all too

numerous – consider, for instance, the famous “Step’ Mozdokskaya” (Belyaev

1971: 61-2), where each line of the text, a four-foot trochee with masculine

endings, is followed with a long sigh “A-akh!” The music reflects neither the

trochee, nor the 5+5 meter of another variant of this text: “Uzh tï step’ moyá,

/Step’ Mozdókskaya” – it is an elaborate and ornate cantilena (Example 2):

Уж ты степь ты, моя степь,(ах) Uzh tï

step' tï, moya step', (akh) Sw Sw Sw S

Степь моя

Моздокская,(ах)[22] Step' moyá Mozdókskaya, (akh) Sw Sw Sw S

Example 2: Drawn-out

Song "Step' Mozdokskaya" (Belyaev 1971: 61-2)

Dolzhansky has also noted this

peculiarity:

As a general rule, [Russian folk songs] contain various

melismas; this is why the poetic meter of the text is not usually reflected in

the melody, and the melody is not governed by the poetic meter. Syllabic

settings of poetry in Russian folk songs, where each syllable of the text

corresponds to only one pitch of the melody, are not too numerous.[23]

Metrically regular syllabic setting of

the trochaic tetrameter also exists in Russian folklore and is more

characteristic of children’s songs and dance songs – the two genres that often

display a direct correspondence between poetic and musical meters in any

language (Burling 1966, Brailoiu 1973). This notwithstanding, the majority of

Russian folk songs do not usually preserve the poetic meter of Russian folk

verse. Thus one must speak primarily of the absorption by the professional

composers of poetic, rather than musical, Russian folk meters.[24]

Re-accentuation in Russian Folklore

Before Stravinsky only Lyadov and

Musorgsky set Russian folk poetry to music.[25]

However, literary poems modeled on folk poetic meters were set by virtually all

the composers beginning with Alyabiev (1787-1851), Varlamov (1801-1848), and

Gurilyov (1803-1858). These settings more or less obeyed the rule of prosody –

a topic for ardent discussions within the circle of the Mighty Five and beyond.[26]

It is known that musically conservative Tchaikovsky, for instance, called it

“the capital rhythmic law” and criticized Bortnyansky (1751-1825), whose sacred

concertos he edited and sometimes even rebarred, for not submitting to it fully

(Kholopova 1983: 100).

The

exaggerated lack of correspondence between textual and musical accentuation in

the Russian vocal works of Stravinsky has been noticed by many scholars. It has

become a commonplace to quote the late Stravinsky’s own explanation in Robert

Craft’s retelling:

One important characteristic of

Russian popular verse is that the accents of the spoken verse are ignored when

the verse is sung. The recognition of the musical possibilities inherent in

this fact was one of the most rejoicing discoveries of my life; I was like a

man who suddenly finds that his finger can be bent from the second joint as

well as from the first.[27]

Taruskin bases his entire treatment of

re-accentuation in Stravinsky’s Russian vocal works on this quotation (1996:

1206-36), believing that Russian folk verse features literary accentuation,

which is afterwards “adjusted” by authentic performers of Russian folk song in

accordance with their musical needs.[28]

As an illustration, Taruskin quotes the third stanza of the well-known round-dance

song “Akh vï, seni moi, seni,” which, according to Simon Karlinsky, “the late

Roman Jakobson liked quoting to his students” (see his fn. 138 on p. 1207 and

his Example 15.22, cit. in my Example 3).

In his chapter on

Stravinsky’s chansons russes, Taruskin’s

Russian musical examples are all underlaid with the normative literary accentuation instead of the folk one, as in “Uzh kak po mostú, po mostú, po shirokomu mostú”

(Taruskin 1996: 1207) – instead of the well-known “Uzh kak pó mostu, po móstu,

po shirokomu mostú.” Actually, Roman Jakobson need not have quoted this verse

as a musical example – he could have simply recited it. In fact, the triple

shift of accentuation of “po mostu” is caused primarily by the requirements of

the regular poetic meter, the trochaic tetrameter with (alternately) feminine

and masculine endings. Besides, all the three variants of “po mostu” coexist on

equal terms in folk verse. They are examples of the so-called “folk

accentuation” (see my explanation below):

Уж как по

мосту, по

мосту,

Uzh kak pó mostu, po móstu, Sw Sw Sw Sw

По

широкому

мосту[29]

Po shirókomu mostú Sw Sw Sw S

Example 3: Round-dance

Song "Akh vï, seni moi, seni," 3rd Stanza (Taruskin 1996: 1207)

Another point of departure for Taruskin’s ideas was Evgeniya Linyova’s

preface to her first volume of The Peasant

Songs of Great Russia as They Are in the Folk’s Harmonization (1904): “The

accent in folk song moves from one syllable to another within a word or from

one word to another within a verse, according to the demands of sense in verse

or melody, which are closely bound together and mutually influential” (Linyova

1904I: xvi, cit. in Taruskin 1996: 1213).[30]

However, Stravinsky-Taruskin-Linyova’s explanation of the re-accentuation

phenomenon does not stand apart as something new and original. In fact, this explanation

reflects the tendency of some late 19th-century/early 20th-century linguists to

attribute the irregularity of Russian folk verse to the complexity of the music

of Russian folk song – the so-called “musical theory” (muzïkal’no-taktovaya teoriya) of Russian folk verse (Korsh 1901) – and is neither complete nor

accurate.[31]

It is accepted today among linguists that the problem of re-accentuation in

Russian folk verse is primarily a philological, and only secondarily an

ethnomusicological problem. As Bailey has shown in his pioneering study (1993),

(1) the standard literary Russian language accentuation differs significantly

from the one of folk poetry,[32]

(2) the shifted accentuation is a normative feature of Russian folk verse, not only Russian folk song,[33]

and (3) although the shifted accentuation often occurs in order to coordinate

the two rhythms, poetic and musical, in many cases, it is the Russian folk poetic meters that make the shifted

accentuation necessary.[34]

Another reason, touched upon by Kholopova, who justifies Bortnyansky’s

re-accentuation by the oral performance practice of old Slavonic liturgical

texts (Kholopova 1983: 101), is a link between re-accentuation and phonetics.

As Vasina-Grossman points out (1972: 31), in Russian speech (as well as, for

that matter, in English and German), only stressed vowels are phonetically

clear, while the rest have some sort of mixed or reduced pronunciation. In this

aspect Russian differs, for instance, from the Italian language, where all vowels

are always pronounced clearly. It is known that the place of an accent in the

Russian language is not fixed – as opposed to the Czech, Polish, or French

languages, where the stress always comes on the first, penultimate, or last

syllable of any word, respectively. As to the ways of accentuation of a

stressed syllable in any language, they are at least three: intensity,

duration, and pitch. Some languages use only one of these properties (as, e.g.,

the English language uses intensity, modern Greek uses duration, and Chinese

and Vietnamese use pitch), while others use a combination thereof. In the

Norwegian and Swedish languages, for example, musical accent is accompanied by

an amplification of volume. In the Russian language, a stressed vowel is both

slightly longer and louder in

comparison with the rest; therefore, every clearly pronounced, prolonged or

simply sung Russian vowel could be easily perceived as stressed.

Therefore, it is not surprising that many verse theorists have always

regarded Russian folk verse as being made up of accents of different strengths

at different places. In the beginning of the 20th century, a theory existed

(which, by the way, also belonged to F. E. Korsh) that regarded dactylic

endings as double-stressed, for it is precisely the final syllable of the line that is often prolonged in folk songs

(“krasna dévitsà,” “dobrïy mólodèts,” “chudo chúdnoè,”

etc.). On the other hand, the investigators of the 18th century beginning with

Tred’yakovsky (1752) regarded “dóbrïy mólodets” as a “trochee-dactyl,” ignoring

the secondary final stress altogether. From the 19th century onwards, a theory

of clictics was popular: the main

phrasal accent falls on the middle syllable of the 5+5 meter, while all other

words lose their word accents and become proclictics

(“krasna dévitsa,” “dobrïy

mólodets,” “chudo chúdnoe”) or enclictics

(“okeán-more”). At present, the accepted view is that of Taranovsky who

was the first to introduce the notions of “word accent,” “phrasal accent,” and “accentual

dissimilation” with its constants and tendencies. The author explained that the

order of parts of speech in a pentasyllabic phrase is what makes a difference

in the accent order: “In phrases like ‘vo chistó polyò’ [adjective + noun] the

accent is usually shifted backward, in phrases like ‘kònya dóbrogo’ [noun +

adjective] forward. In both cases, the strongest phrasal accent always falls on

the middle syllable, while weaker word accents fall on other words.”

(Taranovsky 1956, cit. in Bailey 2001: 195). I will summarize this clash of

opinions below:

SwSww Tred’yakovsky

wwSwS Korsh

wwSww The theory of clictics

SwSwS Taranovsky-Bailey

Thus

the Russian folk 5+5 meter is built around one main phrasal accent, placed in

the middle of a hemistich and dominating other word accents in the hemistich. A

similar hierarchy of accents – although more differentiated and more obvious to

our perception – is intrinsic to music at the stage of barring notation

(roughly from the 16th century onward), which perhaps could explain the

following confession made by the younger Stravinsky in Chroniques de ma vie:

What fascinated me in this verse was

not so much the stories, which were often crude, or the pictures and metaphors,

always so deliciously unexpected, as the sequence of the words and syllables,

and the cadence they create, which produces an effect on one’s sensibilities

very closely akin to that of music. [35]

But

as far as Stravinsky’s chansons russes

are concerned, where unjustified re-accentuation abounds, this is not “the

whole truth” either. There exists yet another type of interdependence: that

between re-accentuation and musical intonation. In his 1972 article, Kharlap

draws attention in passing to a case of re-accentuation, driven by the need to

raise the reciting pitch in accordance with a more or less fixed melodic

formula. What Linyova and Taruskin call “logical accent” – a rather subjective

and somewhat outdated term in Russian metrics[36]

– Kharlap (1972: 230-1) describes as a balance between a pair of emphases found

in each hemistich, one high and one low, arsis

and thesis, both of equal importance.[37]

Their distance from each other, as well as the number of syllables in each of

the two hemistiches, is only approximately

the same (1972: 230-1, italics mine). Using numerous examples, mostly taken

from epic folk verses, the author demonstrates that arses are usually placed one full step higher than theses in melody.

Thus the need for preservation of the same descending melodic line in each

poetic line of the stanza (something typical of epic folk songs) might

occasionally cause a change in normal accentuation:

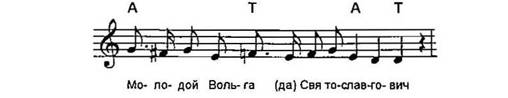

Жил

Святослав

девяносто

лет, Zhíl Svyatoslàv devyanósto lèt,

Жил

Святослав да

переставился.

Zhíl Svyatoslàv da perestávilsyà.

Оставалось

от него чадо

милое, Ostaválos’ ot negò chado míloè,

Молодой

Вольга (да)

Святославгович.[38] MOlodoy Vol’gà (da) Svyatoslávgovìch.

This

is a bïlina, a large-scale

mythological epic, which is nowadays generally considered to be a three-stress

tonic verse (arsis and thesis in each hemistich are marked with the symbols ´

and `). The biggest problem, says Kharlap, is that if Russian folk meters are

viewed as tonic, the need for additional words – conjunctions, interjections,

particles like “(da)” in the verse above, etc. – employed by performers, as

well as for shifted stress in general becomes unclear (1972: 228). Thus,

Kharlap says, the shift of accent in “molodóy” of the fourth line cannot be

explained by any other reason than by the need to raise intonation at the

beginning of the line in compliance with the already established arsis and thesis (see his musical example on p. 258, copied in my Example 4,

arses and theses are shown above).

Молодой Вольга (да) Святославгович

MOlodoy Vol’gà (da) Svyatoslávgovìch.

Example 4: Bïlina "Vol'ga i Mikula," 1st Stanza, 4th

Line (Kharlap 1972: 258)

Sometimes,

however, with the main intonation being preserved, fluctuations in the size of

a hemistich and in the placement of accents are possible. Thus the line

‘Mólodoy Vol’gà (da) Svyatoslávgovìch’ can be read, without destroying the meter, with the literary stress on ‘molodóy’

instead of the bïlina-stress ‘mólodoy.’ Therefore, although

the musical structure is quite clear from the text here, it is sometimes useful

for clarification of the rhythmic structure of the verse to know how it is

sung.[39]

The complexity of the re-accentuation issue

thus becomes even more pronounced: Stravinsky, Linyova, and Taruskin all seem

right in that in certain cases the

shift of accent in Russian folk songs is not required by the metric formula of

the verse but is caused by the urge to maintain the established melodic

structure. Such cases are genre-specific and thus cannot lay claim to be a

general rule, because this type of re-accentuation is not typical of faster

genres of Russian folk songs where the metric scheme is more regular and the

vocal melody is less flexible than in bïlinas. These faster genres often feature a different

type of re-accentuation (see below).

Russian Folk Versification and the Problem of

Incomplete Poetic Feet

Since

re-accentuation is an evident feature of both Russian folk verse and Russian

folk song, there have been numerous attempts to explain this phenomenon from

the point of view of both musicians and linguists. However, these attempts

often resembled a search for one unknown quantity through another, even lesser

known one. Indeed, the main stumbling block has often been the irregular metric

scheme of Russian peasant poetry. In the final part of this article, I will

shed some light on the distinction between the “foot” (stopnaya), “tonic” (tonicheskaya),

and “musical” (muzïkal’no-taktovaya)

theories of Russian folk versification. This distinction is necessary,

primarily, in order to better understand the differences between tonic

(irregular) and isometric (regular) folk poetic structures discussed above, and

secondarily, because it can help clarify the phenomenon of “incomplete poetic

feet.” In its turn, the notion of “incomplete feet” will bring us to the

discussion of the last type of Russian folk re-accentuation.

The

question of metrics in Russian folk verse was first put forward in the middle

of the 18th century by Tred’yakovsky (1752), one of the two reformers – along

with Lomonosov – of Russian literary versification according to western

European standards. Tred’yakovsky’s “foot” theory viewed Russian folk verse as

tonic-syllabic (sillabo-tonicheskiy stikh),

that is, as consisting of a constant number of identical poetic feet per line.

According to this theory, all metric curiosities result from a combination of

different poetic feet, as in the familiar “trochee-dactyl” “dóbrïy mólodets.”

However, it was soon found that many folk metric phenomena (as, e.g., the 5+5

meter) could not be explained by a simple combination of two heterogeneous feet

into one. Therefore, in the beginning of the 19th century, a critical attitude

toward this theory arose, which later prompted the writings of Vostokov (1817).

Vostokov put forward a completely new concept of word stress, linked to the breathing process during singing or

recitation of a verse. His “tonic” theory denies the existence of poetic feet

in Russian folk verse and regards it as “purely tonic” (chisto-tonicheskiy stikh), that is, a verse that has a constant

number (normally 2 or 3) of main stresses (phonetic, syntagmatic, or logical –

that was still a question to answer) per line. Unlike the “foot” theory, which

was gradually losing its significance during the 19th century, Vostokov’s

highly original concept grew even stronger, spawning later linguistic

doctrines, including the theories of “syntactical feet” by Potebnya (1884) and

of “free meter” (vol’nïy razmer) by

Sokal’sky (1888), the two reference points for Kharlap’s investigations. With

small modifications, this concept ended up in modern textbooks.

However, already in the 19th century, there arose a

discontent with the theory, as it had failed to explain the basic difference

between Russian folk verse and prose. In addition, some works appeared that

directly addressed the insufficiency of accent-counting on the grounds that

“not all four-storeyed buildings are of the same height” (Shtokmar 1952: 43).

At the beginning of the 20th century, Korsh (1901) put forward his “musical”

theory, which regarded Russian folk verse as isochronic (ravnodolgotnïy stikh): the verse is inseparable from its vocal performance and is organized

metrically by its tune. Popular during the period when the first phonographic

records of Russian folk songs were made, this theory did not receive much

scientific recognition afterwards, for it skirted the question of poetic metrics

altogether, having granted the exclusive right to deal with it to

ethnomusicologists (Shtokmar 1952: 106).

This

mass of contradictions began to disentangle in the 1930s, when Russian folk

epic verse became the subject of the “Russian” linguistic-statistical method of

analysis in the writings of Jakobson (1966 [1929]), Trubetskoy (1990 [1937]),

and Taranovsky (1956). Only at the end of the century did Bailey (1993) succeed

in reconciling many controversial viewpoints by considering Russian folk verse

as co-existent in many different metric variants, both tonic and regular, and

sometimes even non-metric (prose-like). Bailey also surmised that tonic verse

was very likely a secondary formation as compared to regular verse, and that it

represented the first step toward the

disintegration of Russian folk versification into prose. The habit of adding

small words in order to adjust the verse to the regular meter – conjunctions,

interjections, particles like “da” in the bïlina

above, etc. – on the part of the performers gradually led to an abuse of this

practice, which was probably one of the causes of this disintegration (Bailey

2001: 378).

Nowadays, the standard scientific

approach to the problem of metrics of Russian folk versification has the genre

of a particular verse as its basis (Propp 1961: 46). The division of Russian

folk verse into epic, lyric, and spoken (skazovïy

stikh), where the first is less metrically regular than the other two, is

accepted by all modern folklorists.[40]

According to Propp, lyric folk songs about love and family are divided into two

parts – protyazhnïe (“sad and slow”

drawn-out cantilena songs) and chastïe

(“happy and rapid” dance and game songs, that is, songs connected with physical

movement) (Ibid.: 14-16). “Happy and rapid” songs can be easily distributed

into musical measures, and the reason for this is simple: the western European

measure system appeared due to the influence of popular dances on the music of

professional composers. In the preface to his collection of lyric folk song

texts (1961), Propp examines several widespread types of the four-foot trochee

– the most characteristic poetic meter of dancing (plyasovïe), round-dancing (khorovodnïe),

and game songs (igrovïe pesni). He

notes that absolute correspondence between poetic feet and musical measures is

quite rare, but he does not elucidate in detail the phenomenon of incomplete (or silent syllable) poetic feet – the main reason behind the formation

of so many kinds of the trochaic tetrameter.

Although extremely widespread in children’s, dance, and game songs,

“incomplete feet” as applied to Russian folklore have never been the subject of

a special study, for the very existence of homogeneous poetic feet in Russian

folk verse is still put into doubt by many linguists. This is why the author of

the present study had to rely on generative linguistic studies of English folk

verse for clarification of this phenomenon (Hayes, Kaun 1996; Hayes, MacEachern

1996, 1998). In my opinion, the concept of “incomplete feet” is merely a

special case of musical isochronism

or temporal equality of the two hemistiches achieved in singing – which was one

of the subjects of the “musical” theory of Russian folk verse. Musical

isochronism, interpreted as a certain “contraction” of two short syllables into

one long syllable, is discussed by linguists beginning from the middle of the

19th century well into the 20th (to repeat: the phonetic difference between

short and long vowels does not exist in Russian). Potebnya (1884), for

instance, has expanded the concept of musical isochronism by applying it to

spoken verse (Shtokmar 1952: 68-69). As concerns Soviet ethnomusicologists, who

have never paid enough attention to the metric structure of Russian folk verse

(Bailey 2001: 27), some of them addressed the issue in detail. Viktor Belyaev,

for instance, the author mostly known in the western world for his outline of Les Noces (1928), explains the

phenomenon as follows:

One of the most widely disseminated meters in the world is

the trochaic tetrameter. This and other poetic meters are often used with

sporadic deviations from standard types – e.g., with omissions of structurally

important syllables from the poetic feet or, vice versa, with extra syllables

inserted into them. Our analysis of this creative method allows us to draw two

important conclusions.

Firstly, the predominance of omitted

syllables in poetic lines is typical of the earliest stage of formation of

poetic meters. It is observed mostly in underdeveloped song cultures and

preserved to our day in children’s folk songs…

Secondly, the predominance of

inserted extra syllables is characteristic of the formation of new poetic

meters and of further development of poetic rhythm in general.[41]

The

author provides numerous musical examples in order to illustrate these two

principles.[42]

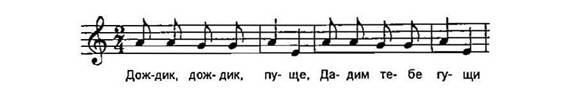

The two excerpts of text below correspond to my musical Examples 5 and 6,

respectively. Belyaev explains ibidem

(and his explanation is entirely pertinent to my Example 5) that in the first

case complete classical 7- or 8-syllable poetic lines (i.e. trochaic lines with

masculine or feminine endings) are replaced with incomplete 6-syllable poetic

lines, although the four-beat structure of the verse remains clear and intact.

In the second case, the insertion of one-syllable words “oy” (oh) and “da” (and)

into the six-foot trochee leads to an appearance of a more heterogeneous poetic

structure with dactylic elements:

Дождик,

дождик, пуще, Dózhdik, dózhdik, púshche, Sw Sw Sw à Sw Sw S

S

Дадим

тебе гущи[43]

DAdim tEbe gúshchi Sw Sw Sw à Sw Sw S

S

Example 5: Children’s Game Song “Dozhdik,

dozhdik, pushche" (Kharlap, 1971: 248)

Горе,

горе

лебеденьку

моему[44]

Góre, góre lebedén’ku moemú Sw Sw Sw Sw Sw S

Ой горе, горе да

лебеденьку

моему

Oy gore, góre da lebedén’ku

moemú à Sww Sw Sww Sw Sw S

Example 6: Lyric Song “Oy gore, gore” (Belyaev

1971: 56)

“The melodic

rhythm in these examples coincides with the rhythm of a cantilena-like

declamation of these poems,” says the author (Belyaev 1971: 55). This last

statement is very important, as it proves that Belyaev is aware of the fact

that the incomplete feet phenomenon belongs to both the realm of poetry (or, to

be precise, poetic performance practice) and that of music. Let me show the

existence of incomplete trochaic feet in the following three excerpts from

children’s verse (Shein 1989: 33-4):

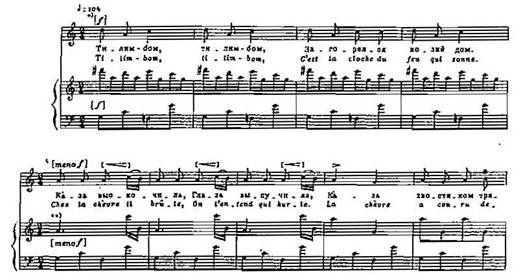

Тилим-бом,

тилим-бом, Tilim-bóm,

tilim-bóm, Sw S Sw

S

Загорелся

козий дом.[45]

Zagorélsya kóziy dom. Sw Sw Sw S

Трах,

трах,

тарарах! Trakh, trakh, tararákh! S S

Sw S

Едет

баба на

волах.[46] Edet bába na volákh. Sw Sw Sw S

Уж дождь дождём, Uzh dozhd’ dozhdyóm, S

S S S

Поливай ковшом![47] Poliváy kovshóm! Sw S S

S

In the first example above, there is

an alternation between a complete four-foot trochaic line with a masculine ending

and a four-foot trochaic line with two incomplete feet. In the second example,

there are as many as three incomplete feet in the first line. Finally, in the

first line of the last example, all trochaic feet are incomplete.

Sometimes the organizational potential of the trochaic

tetrameter is so strong that it outweighs other poetic meters. Consider these

two examples, the second of which is supplied with music (Example 7):

Жила-была

Дуня, ZhIla-bïla Dúnya, Sw Sw Sw à Sw Sw S

S

Дуня-тонкопряха.[48] Dúnya-tonkopryákha. Sw Sw Sw à Sw Sw S

S

А было у

бабки A bïlo u bábki wSw wSw à

Sw Sw S

S

Четыре

вола. Chetïre volá.

wSw wS à

Sw Sw S

Ø

Приехало

к бабке Priékhalo k bábke wSw wSw à Sw Sw S S

Четыре

купца.[49]

Chetïre kuptsá. wSw wS

à Sw Sw S

Ø

Example 7: Lullaby "A

bïlo u babki chetïre vola" (Rubtsov 1967: 196)

In the first example, the three-foot trochee is “distributed into four measures

in singing” (Propp 1961: 45) precisely because the third complete trochaic foot in the poem turns into the last two incomplete trochaic feet in the song.

The second example, taken from Rubtsov (1967: 196), shows a very curious

transformation of the amphibrachic dimeter of the spoken verse into a trochaic

tetrameter with incomplete feet in the music. Moreover, the normative literary

accents of “A bïlo,” “Chetïre” and “Priékhalo” are fore-shifted in the process of this

transformation: “A bïlo,” “ChEtïre” and “PrIekhalo.” Prima facie, one would consider this example a perfect illustration

of the Stravinsky-Taruskin-Linyova theory. In fact, such transformation is only

a matter of altering the metrical organization of the verse during declamation.[50]

Although the spoken verse resembles children’s nonsense poems, its musical

embodiment suggests a lullaby – a genre that tends to favor regularity and slow

tempo more than anything else. Rubtsov surmises that the tune and the verse

might have existed independently of each other, and that this text could have

been taken by the performer merely for lack of a more appropriate one (Ibid.).

The problem of incomplete feet leads

us to the last, very special type of Russian folk re-accentuation – the one

that is there for color effect and nothing else. This type mainly concerns

children’s spoken verse pribaoutki,

as well as dance songs and game songs, performed solo or in a group. As in the

two previous cases, this type of re-accentuation is not evident from a printed

text and is indeed “fully revealed only in singing” (Taruskin); however, a

metrically organized declamation will also give a good idea of it. This type

concerns an immediate repetition of one and the same word, which keeps the main

metric parameters intact but slightly shifts the agogic emphasis from a

stressed syllable to an unstressed one. Kholopova (1983: 146) calls this type

“accentual variation of a word-motive” and mentions several cases of its

employment by 18th- and 19th-century Russian composers. Shtokmar (1952: 204-5)

has also noted this peculiarity: “A play of overt, even provoking stress shifts

is finding its advocates and gradually becoming legalized by the poetic folk

tradition. There appear certain verses where all accent variants of one and the

same word are catalogued, as it were, by the folk singer.” Consider, e.g., the

shifts of accents in “lúgu” (meadow in the dative), “mólodtsa” (fine fellow in

the genetive), and “boyús’” ([I’m] afraid) (Shein 1989: 65-6):

Как по

лугу, по лугу, Kak po lúgu, po lugU, Sw Sw Sw S

По

зелёному

лугу[51] Po zelyónomu lugU Sw Sw Sw S

Как у

молодца,

молодца Kak u mólodtsa, molOdtsa Sw Sw Sw Sw

Разгорелися

глаза[52] Razgorélisya glazá Sw Sw Sw S

Не

боюсь я

вечной муки,

Ne boyús’ ya véchnoy múki, Sw Sw Sw Sw

Боюсь

с миленьким

разлуки[53] BOyus’ s mílen’kim razlúki Sw Sw Sw Sw

As

a matter of fact, this type of re-accentuation can only be explained by using

the notion of incomplete feet. Here is the beginning of the famous round-dance

folk song “Oh we sowed the millet,” mentioned by Taruskin apropos Stravinsky’s “rejoicing discovery”:

А мы просо

сеяли, сеяли![54] A mï próso séyali, seyalI! Sw

Sw S Sw Sw S

Ой, дид-Ладо! Сеяли, сеяли! Oy, did-Ládo! Séyali, seyalI! Sw Sw S Sw Sw S

Example 8: Round-dance Song "A mï proso

seyali" (Taruskin 1996: 1209)

This three-stress

tonic verse becomes surprisingly regular (trochaic) in the music.[55]

The interplay of accents in “seyali” is due to the “incomplete + complete” foot

combination in the former case and the “complete + incomplete” foot combination

in the latter case (S Sw vs. Sw S). The accent, as it were, “jumps over”

from the first to the last syllable of the same word. Notice, however, that in

the music the doubling of the rhythmic value coincides with the metric accent

only in the first “seyali,” while the second “seyali” is agogically back-stressed but metrically

fore-stressed (“sèyalí”).

Conclusion: What Does It All Have to Do

with Stravinsky?

After the

excursus into the area of Russian folk versification, it becomes obvious that

the late Stravinsky’s explanation of the phenomenon of Russian folk

re-accentuation should be taken with caution. Above I argue that the problem of

re-accentuation in Russian folk verse and song is seen today primarily as

linguistic, and only secondarily as an ethnomusicological problem. At the same

time, it would be no more appropriate to dismiss entirely the role of purely

musical factors in the emergence of re-accentuation in Russian folk songs,

especially considering the abundance of “musical” re-accentuation in the famous

folksong collections consulted by Stravinsky from his youth onward. Quite

often, the effect of re-accentuation

can be caused, for example, by a prolongation or melismatic extension of a

syllable while singing (phonetic factor), by a rise of musical intonation in

accordance with the already established melodic pattern (intonational factor),

or by a creative urge to destroy monotony at an immediate repetition of one and

the same word (agogic factor). However, such types of re-accentuation are often

genre-specific: the first is more typical of slow drawn-out songs, the second

is more characteristic of epic songs with their irregular metric structure,

while the third type is found mainly in rapid lyric folk songs – children’s,

dance, round-dance, and game songs, that is, in songs connected with physical movement.

In the light of the above discussion,

the reasons for re-accentuation in Stravinsky’s settings of Russian folklore

texts can be divided schematically into two parts: (1) “primary”

re-accentuation that is already present

in Stravinsky’s text sources, and (2) “secondary” re-accentuation that is

present in the works of Stravinsky but absent

from his text sources. The latter is the most numerous category including

stresses shifted for rhythmic or metric purposes, for semantic purposes, for

preservation of the same melodic material, for color effect, for the purpose of

deviation from the traditional poetic structures, etc. However, the former

predominates in his early settings of Russian folk verse: “rïzhikI,”

“senatOrï,” “sidyuchI,” “glyadyuchI” in “Kak gribï na voynu sobiralis’” dating back to 1904 (“How the Mushrooms Prepared for

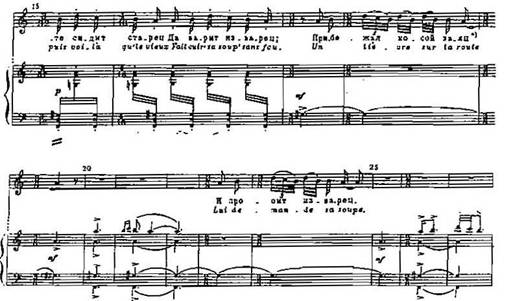

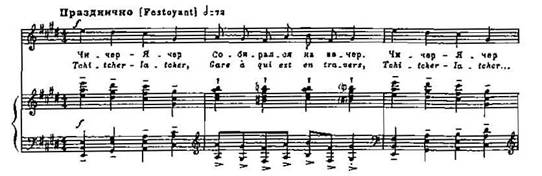

War”), “vskOchila,” “slOmila” in “Sorochen’ka” (“The Magpie”) and “nA vecher” in “Chicher-Yacher” from Souvenirs de mon enfance (1906-13),

“stOit” and “gorYO-toskú” in “Kornilo,” “medovAya” and “zharU” in “Natashka”

from Pribaoutki (1914), “kOza,”

“glAza,” in “Tilim-bom,” “vOrobey,” “tArakan,” ”banyU” in

“Gusi-lebedi” (“Geese, swans”) from Trois

histoires pour enfants (1915-17), etc.[56]

In most such cases, we deal either

with the folk accentuation (“sidyuchI,” Example 9, mm. 5-6) or with a stress

shift caused by a necessity to adjust the poetic line to the regular – mainly

trochaic (although there is one case of an amphibrach in “Natashka”) – folk

verse pattern. The difference between the two causes of re-accentuation is

barely noticeable even to a native speaker; indeed, most of these words are

found in the appendices of folk stress variants in Bailey 1993 (cf. “gorYO” on p. 320,

“dubOm” on p. 323, “medovOy” on p. 329) and

Bailey 2001 (cf. “sidyuchI” on pp.

77, 102). These are all cases of the “primary”

re-accentuation to which Russian folk singers and Russian-speaking readers of

folk poetry rarely pay attention. Who, for instance, would seriously doubt the

presence of two stresses in the word “zAgorélsya,” one primary – the literary stress on the

third syllable – and one secondary, a folk trochaic shift? Accentual dissimilation is responsible for the

difference in intensity of these two stresses.

Под дубом сидючи, Pod

dubóm sidyuchI, Sw S Sw S

На грибы глядючи, [57] Na gribï glyadyuchI, Sw S Sw S

Example 9:

“How the Mushrooms Prepared for War” (mm. 1-11)

© Copyright 1979 Boosey &

Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. Reprinted by permission

Such stress

shifts as “ZAgorelsya koziy dom” (Example 10, mm. 3-4) or “Otkazalis’ rïzhikI”

(Example 11, mm. 84-85) are so widespread in Russian folk tradition that to

call them “re-accentuation” would seem a bit of an exaggeration for a native

speaker (especially a child), who would most likely pass them by unnoticed. But

the stress shifts in “senatOrï” (Example 12, m. 38),

“vskOchila” (Example 13, m. 6), “slOmila” (Example 13, m. 8),

“gorYO-toskú” (Example 14, mm. 11-13) and “medovAya” (Example 15, mm. 5-6) are

quite another matter, because the stress shift here falls on a syllable

adjacent to the literary stress and thus contradicts

the accentual dissimilation, natural to the word itself. Stravinsky, born

linguist that he was, could hardly pass over these stress shifts unnoticed.

Precisely these cases of folk accentuation (notice that they still belong to

the “primary” re-accentuation) were so engraved in his memory that even in old

age he spoke of some curious capacity of folk performers to ignore literary

accents while singing:

One important characteristic of

Russian popular verse is that the accents of the spoken verse are ignored when

the verse is sung. The recognition of the musical possibilities inherent in

this fact was one of the most rejoicing discoveries of my life; I was like a

man who suddenly finds that his finger can be bent from the second joint as

well as from the first.[58]

Тилим-бом, тилим-бом, Tilim-bóm,

tilim-bóm, Sw S Sw S

Загорелся козий дом.

Zagorélsya kóziy dom. Sw Sw Sw S

Коза выскочила, KOza

vïskochila, Sw

S Sw S

Глаза выпучила,[59]

GlAza vïpuchila, Sw S

Sw S

Example 10: "Tilim-bom" (mm. 1-9)

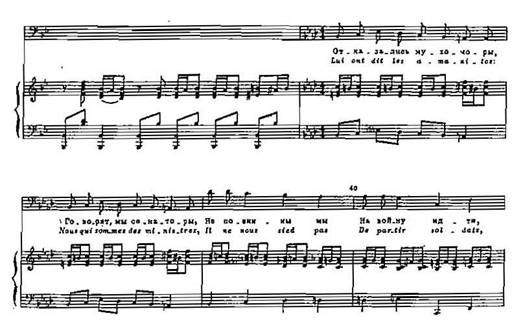

Отказались рыжики:

Otkazális’ rïzhikI: Sw Sw Sw S

«Мы простые мужики,[60] “Mï

prostïe muzhikí, Sw Sw Sw S

Example 11:

“How the Mushrooms Prepared for War” (mm. 83-90)

© Copyright 1979 Boosey &

Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. Reprinted by permission

Отказались мухоморы,

Otkazális’ mukhomórï, Sw

Sw Sw Sw

Говорят, мы сенаторы, [61]

Govoryát, mï senatOrï, Sw Sw Sw Sw

Example 12:

“How the Mushrooms Prepared for War” (mm. 36-40)

© Copyright 1979 Boosey &

Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. Reprinted by permission

Вскочила на ёлочку, VskOchila

na yólochku, Sw Sw S Sw

Сломила головушку. [62] SlOmila

golóvushku. Sw Sw S Sw

Example 13: Souvenirs de mon enfance “Soroka” / "The Magpie" (mm. 6-10)

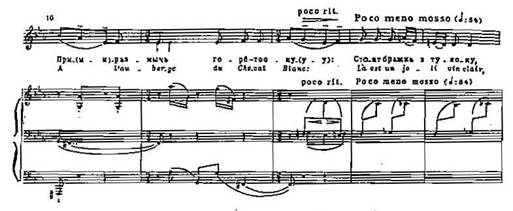

Приразмычь горё-тоску: Prirazmïch’ gorYO-toskú: Sw Sw Sw S

Стоит бражка в туяску, [63] StOit

brázhka v tuyaskú, Sw Sw Sw S

Example 14: “Kornilo” (mm. 10-14)

Сладка медовая, Sladká

medovAya, wSw wSw

В печи не

бывала, V pechí ne bïvála, wSw wSw

Жару не

видала.[64] ZharU ne vidála. wSw wSw

Example 15: “Natashka” (mm. 1-10)

Beginning from the

early-to-middle period of his, so to say, sensitivity to Russian folk verse,

Stravinsky starts to systematically introduce the “secondary” or “musical”

re-accentuation, the one that does not exist in his text sources. But already

in “Vorona” (“The Rook”) from Souvenirs

de mon enfance, he shifts the accent from one stressed syllable to the other,

unstressed one, in “móknet” and “sókhnet” at their repetitions, imitating a

similar procedure in folklore (cf. “A mï próso séyali, seyalI”).

This shift results in an interplay of fore-shifts and back-shifts (Example 16,

mm. 25-28):

Пусть ворона сохнет, Pust’

voróna sókhnet, Sw Sw

S S

Пусть

ворона

сохнет. [65] Pust’ voróna sokhnEt. Sw Sw S S

Example 16: Souvenirs de mon enfance,”Vorona” / ”The Rook” (mm. 23-28)

Opening the first song of Trois histoires pour enfants “Tilim-bom”

as a very conventional setting of a popular nursery rhyme, he soon turns off

the road of predictability, accelerating or slowing down the syllabic rhythm of

the poem as compared to the “prosodic norm” (the term is taken from Ogolevets

1960). In so doing, he introduces utterly distorted accents, alien to the

rhythmic structure of the text (refer back to Example 10, mm. 5-7):

“vïskochIla,” “vïpuchIla” (cf. “vïskochila,” “vïpuchila”), etc. Another interesting case of inversion

of the natural accentuation of the tonic verse is found in the setting of the

first two lines of the irregular tonic verse of “Polkovnik” (“The Colonel”)

from Pribaoutki, which aims to mark

the initial “Ps” of the tongue-twister (Example 17):

Пошёл

полковник

погулять.

Поймал

птичку-перепёлочку.[66]

Poshyól

polkóvnik pogulyát’. à POshyol pOlkovnik pOgulyat’.

Poymál

ptíchku-perepyólochku. à POymal ptíchku-perepyólochku.

Example 17: Pribaoutki, "Polkovnik"/ "The

Colonel" (mm. 6-9, 15-18)

The setting of the tonic verse of

“Starets i zayats” (“The Old Man and the Hare”) also abounds with

re-accentuation of this type, totally unjustified by any logical reason except,

perhaps, by the “contrafact” method of text-setting (Taruskin 1996: 1277):

“kOsoy zaYAts” (Example 18, mm. 18-19), “prosIt izvarEts” (mm. 23-24), and so

on and so forth. These shifts of accents result from a conscious breaking-up on

the part of the composer of the natural prosody of children folk poetry, either

sung or spoken:

Прибежал

косой заяц Pribezhál kosóy záyats à

Pribezhál kOsoy zaYAts

И просит

изварец.[67] I prósit izvárets. à I prosIt izvarEts.

Example 18: Pribaoutki, "Starets i

zayats"/ "The Old Man and the Hare" (mm. 15-27)

“Pesenka medvedya” (“The Bear”,

Example 19), the last one of Trois

histoires pour enfants, stands out from all the chansons russes as the quintessence of Stravinsky’s newly

discovered “new technique of text-setting” (Expo:

120). The most distinctive feature of this song is its metric ambiguity: the quasi-iambic poetic meter perpetually clashes

with the 2/4 meter of the music. The first two lines of the poem, an iambic

dimeter and an anapestic dimeter, are set as if they were trochaic tetrameters:

a “Chicher-Yacher” (see Example 20) type with four incomplete feet and a

“Tilim-bom, tilim-bom” type that is further transformed into a trimeter with

one silent foot. The result of such a conversion of the poetic meters is a

complete distortion of the natural accentuation of the poem: “SkrIpi, nOga,/

SkrIpi, lipovAya” (Example 19, mm. 1-4):

Скрипи,

нога! Skripí, nogá! wS wS à S S

S S à S S

S S

Скрипи,

липовая![68] Skripí, lípovaya! wwS wwS à Sw S Sw S

à Sw Sw Sw

Ø

Example 19: Trois histoires pour enfants, "Pesenka

medvedya"/"The Bear" (mm. 1-7)

Чичер-Ячер Chícher-Yácher S S S S[69]

Собирался

на вечер.[70]

Sobirálsya nA vecher. Sw Sw Sw S

Example 20: Souvenirs de

mon enfance, “Chicher-Yacher” (mm. 1-3)

The Stravinsky analysis above confirms that each of

the two types of Russian folk re-accentuation – “primary” (required by the

regular poetic meter) and “secondary” (caused by the totality of musical

factors) – coexist on equal terms in his music. Similarly, these two tendencies

coexist peacefully in Russian folklore; however, the deliberate and systematic

distortion of prosody – rare if inexistent in folklore – in Stravinsky’s music

gradually acquires a status of a prominent feature. Such distortion will soon

become the quintessence of the composer’s mature style in the late chansons russes, Bayka, Svadebka, and

other works.

Transliteration

The New Grove system of transliterating Russian vowels is adopted with minor

amendments. The letter ы is transliterated as ї, the letter й is transliterated as y, ю and я as yu and ya, ё as yo, e as e, but after hard

or soft signs (both are represented as ’) or between two vowels “e” it is

transliterated as ye. Standard renderings of proper names (Dargomyzhsky, Musorgsky,

Rimsky-Korsakov, Tchaikovsky, Scriabin, etc.) are used.

Symbols for Prosodic Analysis

Accents

(primary ´ and secondary `) are given in the transliterations of Russian folk

poetry. Re-accented vowels are marked in capital letters. Other symbols are

used as follows (the parentheses around the masculine ending are only meant to

show the extra space after S):

S

|

strong syllable |

|

w |

weak syllable |

Sw

|

trochaic foot |

|

wS |

|

Sww

|

dactylic foot |

|

wSw |

amphibrachic foot |

|

wwS |

anapestic foot |

Sw

|

feminine ending (complete foot) |

(S )

|

masculine ending (incomplete foot) |

Ø

|

|

|

primary stress vs. secondary |

|

|

Sww |

Abbreviations

Chron Stravinsky,

Igor. Chronicle of My Life. London:

Victor Gollancz, 1936.

Expo Stravinsky, Igor, and Robert

Craft. Expositions and Developments. London:

Faber and Faber, 1962.

Mem Stravinsky,

Igor, and Robert Craft. Memories and

Commentaries. London: Faber and Faber, 1960.

Selected Bibliography

Aleksandrov, A. 1976 “Zhanrovïe i stilisticheskie

osobennosti ‘Bayki’ Stravinskogo” (The features of genre and style in

Stravinsky’s ‘Bayka’). Iz istorii russkoy

i sovetskoy muzïki 2 (From the history of Russian and Soviet music 2,

Moscow: Muzïka): 200-242.

Asafiev, Boris.

1977 Kniga o Stravinskom (A book

about Stravinsky). Moscow: Muzïka.

___________1982 A Book About Stravinsky. Translated by Richard F. French,

introduced by Robert Craft. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press.

Bailey, James.

1993 Three Russian Lyric Folk Song Meters.

Columbus, OH: Slavica Publishers.

__________2001 Izbrannïe stat’i po russkomu narodnomu stikhu (Selected papers on

Russian folk verse). Translated, edited, and introduced by M. L. Garparov.

Moscow and CEU: Yazïki russkoy kul’turï.

__________2004 Izbrannïe stat’i po russkomu literaturnomu stikhu (Selected papers

on Russian literary verse). Moscow: Yazïki russkoy kul’turï.

Banin, A. A. 1978 “Ob odnom

analiticheskom metode muzïkal’noy fol’kloristiki” (About one analytic method of

musical folklore study). Muzïkal’naya

fol’kloristika 2 (Musical folklore study 2, Moscow: Sovetsky Kompozitor):

117-157.

Belyaev, Viktor. 1928 Igor Stravinsky’s ‘Les Noces’: An Outline.

Translated by S. W. Pring. London: Oxford University Press.

____________1971

“Svyaz’ ritma teksta i ritma melodii v narodnïkh pesnyah” (The relation between

the textual and musical rhythms in folksongs). O muzïkal’nom fol’klore i drevney pis’mennosti (On musical folklore

and ancient writing, Moscow: Sovetsky Kompozitor): 52-64.

____________1972 Musorgsky, Scriabin, Stravinsky. Sbornik

statey (Musorgsky, Scriabin, Stravinsky. A collection of papers). Moscow:

Muzïka.

Birkan, Rafail.

1966 “O poeticheskom texte ‘Svadebki’ Igorya Stravinskogo” (On the poetic text

of Igor Stravinsky’s ‘Svadebka’). Russkaya

muzïka

na rubezhe XX veka (Russian music in the beginning

of the 20th century, Moscow-Leningrad: Muzïka):

239-251.

___________ 1971 “O tematizme

‘Svadebki’” (On the thematic material of ‘Svadebka’). Iz istorii muzïki XX veka (From the 20th-century music history,

Moscow: Muzïka): 169-188.

Brailoiu, Constantin. 1973 “La

rythmique enfantine.” Problèmes d’ethnomusicologie (Genève: Minkoff Reprints):

267-299.

Burling, Robbins. 1966 “The Metrics of

Children’s Verse: A Cross-Linguistic Study.” American Anthropologist 68: 1418-1441.

Dolzhansky, Alexandr. 1973 “O svyazi

mezhdu ritmom russkoy rechi i russkoy muzïkoy” (On the link between the rhythm

of Russian language and that of Russian music). Izbrannïe stat’i (Selected papers, Leningrad: Muzïka): 178-199.

Druskin, Mikhail. 1979 Igor’ Stravinsky. Leningrad: Sovetsky

Kompozitor.

_____________1983 Igor Stravinsky: His Life, Works, and Views.

Translated by Martin Cooper. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gasparov, Mikhail. 2000 Ocherk istorii russkogo stikha (An

outline of history of Russian verse). Moscow: Fortuna Limited.

Golovinsky,

Grigory. 1981 Kompozitor i fol’klor: iz

opïta masterov XIX-XX vekov (The composer and folklore: From the experience

of the 19th-20th-century masters). Moscow: Muzïka.

________________1985 “Stravinsky i

folklor: nablyudeniya i zametki” (Stravinsky and folklore: Observations and

notes). I. F. Stravinsky. Stat’i,

vospominaniya (I. F. Stravinsky. Articles, reminiscences, ed. by G.

Alfeevskaya and I. Vershinina, Moscow: Sovetsky Kompozitor): 68-94.

Grigoriyeva,

G. 1969 “Russkiy folklor v sochineniyakh Stravinskogo” (Russian folklore in the

works of Stravinsky). Muzïka i

sovremennost’ 6 (Music and contemporaneity 6, Moscow: Muzïka): 54-76.

Halle, Morris, and S. Jay Keyser.

1966 “Chaucer and the Theory of Prosody.” College

English 28: 187-219.

Hayes, Bruce, and Abigail Kaun. 1996

“The Role of Phonological Phrasing in Sung and Chanted Verse.” The Linguistic Review 13: 243-303.

Hayes, Bruce, and Margaret

MacEachern. 1996 “Are There Lines in Folk Poetry?” UCLA Working Papers in Phonology 1:125-142.

__________1998 “Quatrain Form in

English Folk Verse.” Language 3:

473-507.

Jakobson, Roman. 1966 “Slavic Epic

Verse.” Selected Writings. Vol. 4

(The Hague: Mouton & Co): 414-463.

Jarustowsky (Yarustovsky), Boris.

1966 Igor Stravinsky. Berlin:

Henschelverlag.

Kharlap, Miron. 1972

“Narodno-russkaya taktovaya sistema i problema proiskhozhdeniya muzïki”

(Russian folk barring system and the problem of music’s origin). Rannie formï iskusstva: sbornik statey (Early

forms of art: A collection of papers, ed. by S. Yu. Nekhlyudov, Moscow:

Iskusstvo): 221-272.

Kholopova, Valentina. 1971 Voprosï ritma v tvorchestve kompozitorov XX veka (The problems of

rhythm in the works of the 20th-century composers). Moscow: Muzïka.

_________________1974 “Russische

Quellen der Rhythmik Strawinskys” (Russian sources of Stravinsky’s rhythm). Die Musikforschung 27: 435-446.

_________________1978 “K voprosu o

spetsifike russkogo muzïkal’nogo ritma. Russkie muzïkal’nïe daktili i

pyatidol’niki” (In reference to the specifics of Russian musical meter. Russian

musical dactyls and pentasyllabic meters). Problemï

muzïkal’nogo ritma: sbornik statey (Problems of musical rhythm: A

collection of papers, Moscow: Muzïka): 164-228.

_________________1983 Russkaya

muzïkal’naya ritmika (Russian musical rhythm). Moscow: Sovetsky Kompozitor.

Kon, Yuzef. 1992

“Metabola i ee rol’ v vokal’nïkh sochineniyah

Stravinskogo” (Metabola and its role in the vocal works of Stravinsky). Muzïkal’naya Akademiya 4: 126-130.

Korsh, F. E. 1901 “O russkom

narodnom stikhoslozhenii” (On Russian folk versification). Sbornik otdeleniya russkogo yazïka i slovestnosti 67/8 (A

collection of papers of the department of the Russian language and philology

67/8).

Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendorf.

1983 A Generative Theory of Tonal Music.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lindlar, Heinrich.

1982 Lübbes Strawinsky Lexicon.

Bergisch Gladbach: Gustav Lübbe Verlag.

Linyova

(Lineva), Evgenia. 1904, 1909 Velikorusskie

pesni v narodnoy garmonizatsii (The Peasant Songs of Great Russia as They

Are in the Folk’s Harmonization). Texts edited by the academician F. E. Korsh.

2 vols. St. Petersburg: Imperial Russian Academy of Sciences.

Lupishko, Marina. 2007

“Stravinsky’s ‘Rejoicing Discovery’ Revisited: The Case of Pribaoutki,” Mitteilungen der

Paul Sacher Stiftung 20 (March): 19-25.

______________

2006 The “Rejoicing Discovery” Revisited:

Re-accentuation in Stravinsky’s Settings of Russian Folk Verse. Ph. D.

dissertation, defended at Cardiff University.

Mazo, Margarita. 1990 “Stravinsky’s Les Noces and Russian Village Wedding

Ritual.” Journal of American

Musicological Society 43: 99-142.

Meyen, Yelizaveta. 1978 “‘Pribaoutki’

I. Stravinskogo” (I. Stravinsky’s ‘Pribaoutki’). Iz istorii russkoy i sovetskoy muzïki 3 (From the history of Russian and Soviet music 3, ed. by M.

Pekelis and I. Givental’, Moscow: Muzïka): 195-208.

Monelle,

Raymond. 1989 “Music Notation and the Poetic Foot.” Comparative Literature 3: 252-269.

Ogolovets, Alexey. 1960 Slovo i muzïka v vokal’no-dramaticheskikh

zhanrakh (Speech and music in vocal-dramatic genres). Moscow: Muzgiz.

Paisov, Yury. 1973 “O ladovom

svoyeobrazii ‘Svadebki’ Stravinskogo” (On the harmonic peculiarity of

Stravinsky’s ‘Les Noces’) I. F.

Stravinsky. Stat’i i materialï (Stravinsky. Papers and materials, ed. by L.

S. D’yachkova and B. M. Yarustovsky, Moscow: Sovetsky Kompozitor): 214-250.

__________1985 “Russkiy fol’klor v

vokal’nom tvorchestve Stravinskogo” (Russian folklore in the vocal works of

Stravinsky). I. F. Stravinsky. Stat’i,

vospominaniya (I. F. Stravinsky. Articles, reminiscences, ed. by G.

Alfeevskaya and I. Vershinina, Moscow: Sovetsky Kompozitor): 94-128.

Popova, T. V. 1955, 1962 Russkoe narodnoe muzïkal’noe tvorchestvo (Russian folk music). 2

vols. Moscow: Muzgiz.

Propp,

Vladimir. 1998 Sobraniye trudov (A

collection of works). 2 vols. Moscow: Labirint.

Propp,

Vladimir, ed. and intr. 1961 Narodnïe liricheskie pesni (Lyric folk

songs). Leningrad: Sovetsky Pisatel’.

Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolay. 1946 Sto russkikh narodnïkh pesen (One hundred Russian folk songs).

Moscow, Leningrad: Muzgiz.

Rubtsov, Feodosiy. 1967 “Sootnoshenie poeticheskogo i muzïkal’nogo

soderzhaniya v narodnïkh pesnyakh” (Correlation between the poetic and musical

contents in folksongs). Voprosï teorii i

estetiki muzïki 5 (Theoretical and esthetical issues in music 5, Leningrad:

Muzïka): 191-229.

Ruch’yevskaya, Ekaterina. 1966 “O

sootnoshenii slova i melodii v russkoy kamernovokal’noy muzïke nachala XX veka”

(On the correlation between text and melody in the Russian chamber vocal works

of the beginning of the 20th century). Russkaya

muzïka na rubezhe XX veka (Russian music in the beginning of the 20th

century, Moscow-Leningrad: Muzïka): 65-110.

Sergeyev, L.

1975 “O melodike Stravinskogo v proizvedeniyakh russkogo perioda tvorchestva”

(On Stravinsky’s melody in his Russian works). Voprosï

teorii muzïki 3 (Problems

of music theory 3, Moscow: Muzïka):

320-334.

Shein, Pavel. 1989 Velikorus v svoikh pesnyakh, obryadakh, obïchayakh, verovaniyakh,

skazkakh, legendakh i t. p. (The Great Russian in his songs, rituals,

customs, beliefs, tales, legends, etc.). Moscow: Sovetskaya Rossiya.

Shtokmar,