Stravinsky and Russian Poetic Folklore

Marina Lupishko

Igor

Stravinsky’s ambivalent attitude towards Russian folklore parallels in some ways

his ambivalent attitude towards his native land: venerated in the early years

of his first emigration, it gradually became an object of his bitter criticism

and negation, as seen in the following passage about Bartok in Conversations with Igor Stravinsky: “I

could never share his lifelong gusto for his native folklore. This devotion was

certainly real and touching, but I couldn’t help regretting it in the great

musician.”[1] The word “never” is an exaggeration, of course, since as

late as 1928 the composer of Apollo was still trying “to discover a melodism

free of folklore.”[2] By 1930, he pledged his non-participation:

Obviously, some composers have found their best inspiration

in folk music. In my opinion, popular music has nothing to gain by being taken

out of its frame. It is not suitable as a pretext for demonstrations of

orchestral effects and complications. It loses its charm by being déracinée.

One risks adulterating it and rendering it monotonous. [3]

Eventually,

the very word “folklore” became associated for Stravinsky with the notion of

narodnost’ (“folkness”), which, together with partiynost’ (“party membership”),

comprised the two pillars of the infamous prescribed artistic method of

Socialist Realism.[4]

As a result, one of the greatest Russian composers of the twentieth century has

been long viewed by the official Soviet musicologists as a

renegade-cosmopolitan[5]

or, at best, a pseudo-nationalist, who, having started his career within the

tenets of Diaghilev’s enterprise, turned off the road of neo-nationalism as

soon as following it was no longer profitable.[6]

But perhaps these critics of the composer, along with those western ones who

like to emphasize the multi-faceted, eclectic nature of his talent, should be

reminded of what the 80-year-old Stravinsky admitted to the interviewer from

Komsomol’skaya Pravda during his reconciliatory trip to the

I have spoken Russian all

of my life, I think in Russian, my way of expressing myself [slog] is Russian.

Perhaps this is not immediately

apparent in my music, but it is latent there, a part of its hidden nature.[7]

Today

Stravinsky’s significance as one of the true followers of Russian musical

nationalism in the 20th century cannot be disputed. As Taruskin has

shown in his fundamental study (1996), the composer’s adherence to this

tradition was based on several different factors, of which the conscious

devotion to the aesthetic principles of his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov is not the

most prominent. According to Taruskin,[8]

what pushed Stravinsky into conscious exploration of Russian folklore was,

first and foremost, the unexpected loss of the possibility of absorbing it in

the subconscious way in his homeland.

At the beginning [of the war] he was a Russian aristocrat

and (in the West at least) the undisputed heir to his country’s magnificent

half-century of achievement as purveyor of exotic orchestral and theatrical

spectacle to the world. At its end he was a stateless person facing uncertain

prospects…[9].

In

July of 1914, when the composer was leaving

Do the songs betray any homesickness for

Leaving behind his childhood, marked

by several personal contacts with peasant culture,[14]

the 32-year old Stravinsky wanted, as it were, to reopen access to the magic

world of Russian folklore to his own offspring. His wife and four children (the

youngest daughter, Milena, was born on January 15, 1914) were by this time his

only inspiration and only audience, since the war made it no longer possible

for Ballets Russes to perform on a regular basis. “The world of folk poetry

also provided a much needed temporary escape from the hothouse sophistication

of the Diaghilev-Paris ambience,”[15] since the

composer no longer had a deadline to work to.

Richard

Taruskin attributes the crystallization of the composer’s style during the

Swiss period to his acquaintance with the historico-political current of

Eurasianism, popular at that time among the Russian intellectual emigration.[16]

Taruskin uses the term “Turanian” (from “Turan’” - the Persian name for the vast territory

extended from the Carpathians to the

More

accurately, the catalyst for Stravinsky’s growing Russophilism was, as Taruskin

also implies, his collaboration under Diaghilev with the painters of the “World

of Art” circle (Golovin, Bakst, Benois, Roerich) and especially with the

founders of Russian Futurism, Mikhail Larionov (1881-1964) and his wife Natalia

Goncharova (1881-1962). These two developed the costume designs and stage

settings for Bayka and Svadebka, respectively (staged in 1922 and 1923), and

were among Stravinsky’s closest friends during his Swiss and Parisian years.[18]

Working in the style of the lubok (a folk kitsch art form), the painters aimed

towards abstraction in their use of bright solid colours, geometric forms and

simplified folk motifs, which often made them equal participants in shaping the

libretto and the choreography of the staged works.

Another

close friendship - that with the French-Swiss writer Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz

(1878-1947) - started and grew into collaboration in

[being] a man and a complete man, which is to say, refined

and at the same time primitive; sensitive to every complication, but also to

the elementary; capable of the most complicated combination of the spirit and

also of the most spontaneous and direct reactions. Because one must be both

savage and civilized, it is not necessary to be only a primitive, but it is

necessary to be also a primitive.[20]

Beginning

from 1916 Ramuz became the composer’s principal translator of almost all the

latter’s Russian works of the Swiss period (except PodblyudnVe), although the

former knew no Russian and had to rely on Stravinsky’s word for word

translations. In 1918, Ramuz produced the libretto of Histoire du soldat - their first and only fully collaborative

work.

Overall,

the six years of the “Swiss exile”(1914-20) played a very important role in the

coming-to-be of Stravinsky. During this period not only was Svadebka - the “Turanian pinnacle”[21]

- essentially completed but also a “bouquet” of settings of Russian folk texts

including Bayka was produced, and at the same time the basis of the ensuing

neo-classical period was laid (Easy Pieces, Histoire du soldat, Pulcinella). In

his afterword to I. Stravinsky, publitsist i sovesednik, an impressive

collection of interviews and articles by the composer, Varunts points out that

the general direction of Stravinsky’s development during this period was a

search for new forms of expression, on the one hand, and a further liberation

from the grip of the programme music principle, inherited from his teacher

Rimsky-Korsakov, on the other. A new artistic concept - the author calls it

antiprogrammnost’ or antisyuzhetnost’ [22]

- was gradually arising in his mind during this time, paralleling similar

processes in the contemporary music of the second decade of the 20th

century. First stated in 1913 as a rebellious manifesto against the passé aesthetics of the 19th century (the first

quotation below), the concept was made more precise in 1924:

Music can be married to gesture or to words - not to both

without bigamy.[23]

Even if at first glance the music is combined with its

literary or fine art origin, in my artistic concept

it retains all the traits of absolute music. The Firebird,

Petrushka, and some other works of mine

gained recognition as samples of programme music or even

descriptive music… My latest works

do not contain any foreign artistic admixtures. True, some

traces of my former views can still be

found in Histoire du soldat and Pulcinella…[24]

The

vocal works of the Swiss period, although by genre direct heirs of Romanticism,

also testify to the growing awareness of these matters. The turning point, says

Varunts,[25]

came in the summer of 1913 when Stravinsky, having scarcely recovered from a

severe illness after the notorious premiere of Le Sacre, settled in Ustilug and

started Souvenirs de mon enfance. In these three songs completed in October

1913,[26]

we witness a composer amusingly at play with the sonoric and accentual side of

the word material. “It is perfectly clear,” says Varunts, “that from now on the

composer begins to give preference not so much to the semantic side of the

verse, as to its sound.” [27]

Svadebka (Les Noces) is known to have been conceived as early as 1912.[28]

Already by the summer of 1913, Stravinsky was actively looking for a suitable

text material, as appears from his correspondence with Stepan Mitusov.[29]

When the composer finally made his long-awaited trip to Ustilug and

One important characteristic of Russian popular verse is

that the accents of the spoken verse are ignored when the verse is sung. The

recognition of the musical possibilities inherent in this fact was one of the

most rejoicing discoveries of my life....[31]

Here

one is reminded of the quasi-rhetorical question, raised by Mikhail Druskin in

his monograph:

Where and how did Stravinsky encounter this folk-song – as a

child in

Like much else in Stravinsky’s personality, this remains a

puzzle.[32]

But

there is hardly any puzzle here. The answer is simple: from books. The research

of modern scholars (Birkan, Paisov, Vershinina, Taruskin, Varunts, Mazo, etc.)

has shown that Stravinsky mastered the subject of Russian folklore, both sung

and spoken, so well that by the time he composed Bayka and Svadebka it became

his “second nature.”[33]

He obviously studied at the very least a dozen books on Russian folklore,

reading carefully not only the material itself but also the prefaces and

commentaries to it: Kireyevsky’s Songs Collected by P. V. Kireyevsky,

Afanasiev’s three-volume Russian Folk Fairytales, Sakharov’s Legends of the

Russian People, Tereshchenko’s Manners and Customs of the Russian People, Shein’s

Russian Folk Songs and The Great

Russian in His Songs, Rituals, Customs, Beliefs, Fairytales, Legends, etc.,

Rozhdestvensky-Uspensky’s Songs of the Russian Sectarians-Mystics and other

books.[34] Moreover, the composer made notes to himself

to look up every word he was not sure about in Vladimir Dahl’s Explanatory

Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language.[35]

All this is not surprising. Both Varunts and Druskin had noticed the

exceptional diversity of interests, continually demonstrated by the composer in

the course of his long life:

It may be said without fear of exaggeration that no

contemporary expatriate composer could compare with Stravinsky in knowledge of

the present-day world, whether it was in philosophy, religion, aesthetics,

psychology, mathematics, or the history of art. Nor was he content to remain

simply well informed, he wished to have a specialist’s understanding of every

subject, his own opinion on every problem and his own attitude to every point

under discussion. Right into extreme old age he was an avid reader and always

had a book in his hands. His library in

[W]e are only approaching the complete assessment of

Stravinsky as one of the greatest persons of encyclopedic knowledge of our

time. The breadth of problems touched upon by the composer with a greater or

lesser degree of insight is astonishing. Indeed, Stravinsky seems to be expert

in virtually all areas. He is interested in literature, philosophy, religion,

biology, mathematics, demography, medicine, geography, linguistics, and - of

course - music.[37]

Out of the last

(incomplete) list of subjects, the one of interest to us at this point is

linguistics. Beginning from the late summer of 1914, after having sketched the

provisional libretto for Svadebka, Stravinsky got temporarily carried away by

something largely unconnected to the peasant wedding ritual based on songs -

the genre of spoken verse (skazovVy stikh) known as pribaoutki. To the texts of

the “Pribaoutki” chapter from the third volume of Afanasiev’s Russian Folk

Fairytales Stravinsky sets the entire Pribaoutki cycle, as well as some numbers

from Trois histoires pour enfants, Berceuses du chat, and Bayka. That is to

say, pribaoutki – miniature folk nonsense poems with their lack of logic,

frequent onomatopoeia, and intricate combinations of images and sounds - rather

than the wedding songs from the Istomin-Dyutsh (1894), Istomin-Lyapunov (1899)

and other folksong collections[38]

- were his main musical inspiration at that time. Druskin quotes Stravinsky’s

opinion from his personal conversation with the composer during the latter’s

trip to

himself in a

letter to his mother, dated 10/23 February, 1916 (the first quotation below),

and by Grigoriy Alexinsky (1879-1967), an exiled politician, in a letter to the

composer, dated 4/17 April, 1916:

Please

send me as soon as possible (you’ll find these at Jurgenson’s [

My acquaintance with you, although of short duration,

gave me much [food for thought] regarding my views of art in general, and

taught me many new things. In particular, it was pleasantly surprising to

discover that you - the person who, let me confess, I had considered before our

first meeting to be a ‘decadent’ and so on

- are turning to the very source of Russian folk poetry and life in

order to find there a stimulus for your fantasy and inspiration.[42]

It

should be re-emphasized that the main impulse for the production of all the

Russian vocal works of the Swiss period (perhaps, with the exception of

Svadebka which was at first conceived as a quasi-operatic embodiment of a

peasant wedding ritual) was a linguistic interest in Russian folk verse (rather

than Russian folk song), frequently asserted by the composer in his writings,

letters, and interviews.[43]

As if commenting on this peculiarity, Varunts observes that Stravinsky showed

interest in the phonic side of poetry in the course of his entire life, and

that this fact alone distinguishes the composer to his advantage from the

contemporary currents and trends in Russian literary verse (Khlebnikov and

other futurists)[44],

and draws him closer to one of the greatest Russian poets of the 20th

century, Marina Tsvetayeva (1892-1941).[45]

There exist a number of confirmations of this interest in Chroniques de ma vie,

Poétique musicale, in the volumes of conversations with Robert Craft, in

Stravinsky’s published letters and interviews, in the memoirs of Ramuz and

others. From these primary sources we gather that not only the phonic side of

poetic folklore occupied the composer’s imagination, but also the language as

such. As a schoolboy, Stravinsky was obliged to study Latin, Ancient Greek,

French, German, Russian, and Old Slavonic. As a “composer-polyglot,” he

produced text-settings of Russian, French, English, Latin, and Hebrew. Here is

his famous response to a Schoenberg aphorism, the response that embodies the

principle of careful preservation of the source language: “What the Chinese

philosopher says cannot be separated from the fact that he says it in Chinese.”[46]

In Expositions and Developments, Stravinsky recalls:

Bible studies in tsarist schools were as much concerned with

language as with religion because our Bible was Slavonic rather than Russian.

The sound and study of Slavonic delighted me and sustained me through these

classes. Now, in retrospect, most of my school time seems to have been consumed

by language studies, Latin and Greek from my eleventh to nineteenth years,

French, German, Russian, and Slavonic – which resembles modern Bulgar – from my

very first days in the Gymnasium. Friends sometimes complain that I sound like

an etymologist, with my habit of comparing languages, but I beg to pardon

myself for reminding them that problems of language have beset me all my life;

after all, I once composed a cantata entitled Babel.[47]

The

following excerpt from an article by Edwin Allen, Stravinsky’s private

librarian in

Stravinsky was a great reader and read as comfortably in

English and German as he did in French and Russian. His lexicological interests

manifested themselves constantly. An expression in English had to be repeated

in French, German, Russian, and sometimes Italian, as a diverting game that

could never be completed until all the languages were represented. Sometimes trips

to the dictionaries had to be made but more often Stravinsky’s phenomenal

memory for language quickly found the right word or phrase. Butter, for

example, could not be passed at table without verbal extension: maslo

(Russian), beurre (French), Butter (German), burro in Italian but definitely

not in Spanish unless one expected to leave the restaurant on an ass.[48]

Having

observed Stravinsky’s interest in linguistics in general and the sonic side of

poetry in particular, Varunts nonetheless let go unnoticed the composer’s

interest in its metric side. The first conscious exploration of the metrics of

poetry came in 1912-13, with the exposure to the metrics of the Japanese

language in Trois lyriques japonaises, a vocal cycle for small mixed orchestra

and soprano (see Example 1). The unusual metric organization of the settings of

Russian translations of these three miniature poems perplexed some musicians,

notably Derzhanovsky and Myaskovsky. The composer’s published response to

Vladimir Derzhanovsky (1881-1942), the

editor of the Moscow MuzVka periodical, merits a lengthy quotation:

Japanese

songs are written to genuine

Japanese poems of the 8th and 9th centuries AD

(naturally,

in translation [into Russian]). The translator

preserved the exact

number of syllables

and the

word order of

the original. Accents

as such do

not exist in the Japanese language or Japanese poetry.[49]

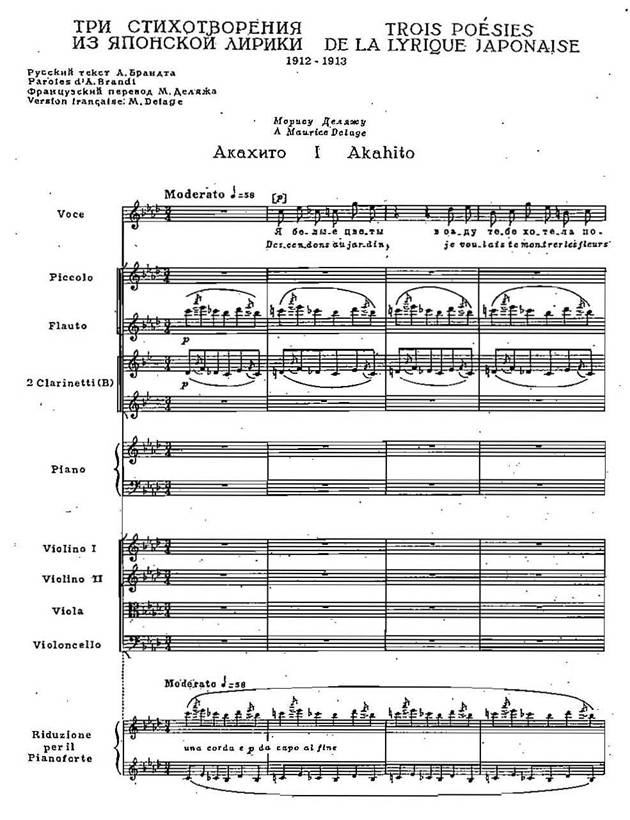

Example 1: Trois lyriques japonaises Opening

Measures

This topic is treated lucidly and in detail in the preface

to the book of Japanese lyrics from which I selected the three poems.[50] I was guided by these

considerations - namely, the absence of accents in Japanese poetry - while composing the

songs. But how could I obtain this effect? The most natural way would be to transfer long

syllables of the poems onto short syllables of the music. In this way, the accents would disappear on

their own, which would fully correspond to the linear perspective of Japanese

declamation…

As regards the queerness of the impression from this

declamation, I am not in the least embarrassed

by it; this

impression belongs to the realm of convention and is simply a matter of habit.[51]

Having acquainted himself with these

“programme notes,” the composer Nikolay Myaskovsky (1881-1950) wrote in a

letter to Derzhanovsky, dated June 20/

The little

Japanese verses are linear, etc.… but

when I was playing and reading these crafty little

tricks, I

always wanted instinctively to rub

my ears

and to shake

my head, in order to get rid of

the

machine-like importunity of this artificial declamation; but

the music is

pleasing to me:

there

is a good

deal of something personal, ‘linearly’ intimate, un-Scriabinesque about it.[52].

At its early stage,

Stravinsky’s interest in the metric structure of Russian folk verse is best

reflected in the sketches and drafts of the chansons russes, Bayka, and

Svadebka in the composer’s archive in

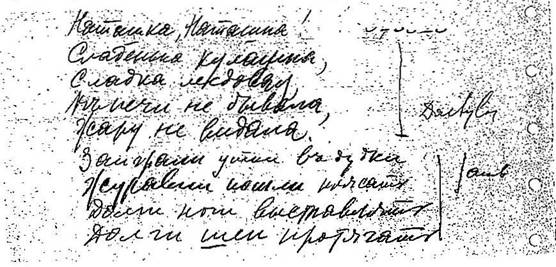

Example 2: From

Sketch for Pribaoutki, Natashka, Prosodic Analysis of Text

The

interest in metrics grows steadily during the ensuing neo-classical period when

Stravinsky, while moving farther and farther away from his native language,

starts using designations for Greek poetic feet freely and more professionally.

Here are some quotations concerning Oedipus

Rex (1926-7), Apollo (1928), and Perséphone (1933-34) from Dialogues and a Diary:

When I work with words in music, my musical saliva is set in

motion by the sounds and rhythms of the

syllables, and ‘In the beginning was the word’ is, for me, a literal, localized

truth.[55].

All of my ‘ideas’ for Oedipus Rex were in one sense derived

from what I call the versification… And what do I mean by ‘versification’? I

can answer only by saying that at present I make my ‘versification’ with series

as an artist of another kind may versify with angles or numbers… [Critics] should

also analyze the nature of the music’s rhythmic manners, the hint for which

came from Sophocles himself or, more precisely, from the metres of the chorus

(especially the simple choriabics, the anapaests and dactyls, rather than the

glyconics and dochmii).[56]

The real subject of Apollo, however, is versification, which

implies something arbitrary and artificial to most people, though to me art is

arbitrary and must be artificial. The basic rhythmic patterns are iambic, and

the individual dances may be thought of as variations of the reversible

dotted-rhythm iamb idea. The length of the spondee is a variable, too, and so,

of course, is the actual speed of

the foot… I cannot say whether the idea of

the Alexandrines, that

supremely arbitrary set of prosodic rules, was

pre-compositional or not… but

the rhythm of

the cello solo

(at 41 in the Calliope variation) with the pizzicato

accompaniment is a Russian Alexandrine suggested to me by a couplet from Pushkin,

and it was one of my first musical ideas. The

remainder of the

Calliope variation is a musical

exposition of the Boileau

text that I took as my motto.[57] But

even the violin cadenza is related to

the versification idea. I thought of

it as the

initial solo speech, the first essay in verse of Apollo

the god.[58]

My first

recommendation for a

Perséphone revival would

be to commission Auden to fit the

music with new words, as Werfel did in La Forza del Destino. The rhythms are

leaden-eared: Perséphone confuse/ Se refuse. (I composed the music for this

couplet on a train near Marseilles, whose rhythm was anapaestic.)[59]

By

the year 1934 the word “versification” (“syllabification”) acquires the meaning

of some universal principle of composition:

I was asked

to write about the music of Perséphone, but since I barely have the time to do

it, I would like to draw the audience’s attention to a single concept which

contains the entire programme of the work: syllabe [Fr., syllable] and,

as a consequence,

the verb syllaber

[Fr., to assemble, to put together, to make verses]. My principal task

was a realization of these two concepts.

Contrary to

the disorganized chaos of sounds in nature, the syllable is always present in

music – an art based of organized

rhythm and fixed

pitch. Between the syllable and

the general sense - that is, the coming-into-being of

the work of art - there is a connecting-link, and this

connecting-link is the word which directs the disoriented motion of a thought

to a logical conclusion..[60]

Stravinsky

says next that the semantic side of a text often hinders the creative thought of

the artist, while the purely sonic side, on the contrary, liberates the

artist’s imagination: “I must say that words, far from helping, constitute for

the musician a burdensome and limiting intermediary.”[61]

As a result, in Perséphone he was more interested in setting “the magnificent

syllabic structure” provided him by André Gide (1869 -1951), than in the drama

per se. At first glance, these statements concern the sonic side of speech in

general, rather than poetry or metrics. However, the following two excerpts are

helpful in understanding that the syllabic structure of the text and, more

broadly, of the music never existed for Stravinsky outside the notions of metre

and rhythm, in so far as metre and rhythm represented for him - respectively -

the result and the process of adding-up of syllables (syllaber in French,

skladyvat’ or slagat’ in Russian). The first excerpt is from a personal

conversation with the violinist Samuel Dushkin in the early 1930s, the second -

from Poétique musicale (1939-40):

In mathematics…

there are numerous ways of obtaining the number seven. The same is true for rhythm. The only difference between them is that the most

crucial for mathematics is the sum total. It is of little importance, whether you add up five and two

or two and five, six and one or one and six, etc. But for rhythm, the sum total – seven – plays a

secondary role. How it is obtained is far more important: five and two or two and five, because five and

two are something absolutely different from two and five.[62]

The laws that regulate the movement of sounds require

the presence of a measurable and constant value: meter, a purely material element

through which rhythm, a purely formal element, is realized. In other words,

meter answers the question of how many equal parts the musical unit which we

call a measure is to be divided into, and rhythm answers the question of how

these equal parts will be grouped within a given measure. A measure in four

beats, for example, may be composed of two groups of two beats, or in three

groups: one beat, two beats, and one beat, and so on…[63]

Beyond

any doubt, Stravinsky’s study of Russian folk songs and poetry had contributed

to the development of this vision of musical rhythm as a combination of equal

and/or unequal metric units.[64]

In his frequent remarks about syllables as something abstract and pure as

opposed to words burdened with meanings and emotions,[65]

the composer rarely reveals to the interviewer the extent to which the syllabic

and poetic-feet structure of Russian folk poetry was the source of his

notorious accent-fluctuating rhythmic thinking. The only notable exception,

perhaps, is an interview given in

Stravinsky tells us that in Oedipus Rex the word is a simple

material which functions musically as a block of marble or a block of stone in

architecture or sculpture. Les Noces, for instance, consists of songs which do

not bear much logical sense, but instead in these poems their sonic and

rhythmic qualities are emphasized. Our language, explains the composer, is

inseparable from emotionality and sensuality, which undermine the musical value

of the word. That is why [in Oedipus Rex] Stravinsky turns his attention to the

dead language of Latin… Stravinsky leaves the Latin text untouched, yet at the

same time he emphasizes syllables, poetic feet, etc.[66]

As

should be expected, rhythm occupies the supreme place in Stravinsky’s hierarchy

of musical means of expression, as seen from an interview given in

Rhythm in my understanding is the music itself. For example,

the works of Bach, which are standards of comparison for us all, consist of

nothing else but rhythm and architecture. Rhythm is an essential and dominating

quality of music. But the Romantic composers have destroyed it with their

infinite vignettes and ornaments of all kinds. I write my music, as they say,

in cold blood.[67]

One is drawn immediately to this

musical-architectural analogy, contained in the last two quotations. As Druskin

shrewdly observes in the corresponding chapter of his 1983 monograph, during

the neo-classical period Stravinsky consciously developed the spatial aspect of

music, possibly inherited from Debussy.[68]

A constant advocate of lucid forms and clear lines, Stravinsky is well-known to

have possessed the eye of an artist - this “supplementary” talent is revealed

not only in his colourful, ornamented and calligraphically immaculate

manuscripts, but also in his numerous observations about the nature of the two

arts, the visual and the temporal. Because this topic is too vast to be treated

in passing, only two pairs of Stravinsky’s statements will be cited here as

examples of his multifaceted nature of musical perception. The first pair is

taken from conversations with Robert Craft (Memories and Commentaries and

Themes and Conclusions, respectively) and is evidence that both visual and

linguistic impressions from real life stimulated to a great extent the

composer’s creativity:

– Has music ever been suggested to you by, or has a musical

idea ever occurred to you from, a purely visual experience of movement, line or

pattern?

– Countless times, I suppose, though I remember only one

instance in which I was aware of such a thing. This was during the composition

of the second of my Three Pieces for string quartet. I had been fascinated by

the movements of Little Tich whom I had seen in

The origins of the ballet [Jeu de cartes]… go back to a

childhood holiday with my parents at a German spa, and my first impressions of

a casino there… In fact, the trombone theme with which each of the ballet’s

three ‘Deals’ begins imitates the voice of the master of ceremonies at that

first casino. ‘Ein neues Spiel, ein neues Glück,’ he would trumpet – or,

rather, trombone – and the timbre, character, and pomposity of the announcement

are echoed, or caricatured, in my music.[70]

The

second pair of comparisons made by the established maTtre Stravinsky is

especially polysemantic for us who study the linguistic aspect of his vocal

works. The first one, borrowed from Goethe, evokes the second, also very

well-known, comparison:

It is impossible to better define the feeling that music

produces on our senses, as to equate it with the impression evoked by

contemplation of architectural forms. Goethe understood this well; he used to

say that architecture is frozen music.[71]

What fascinated me in this verse was not so much the

stories, which were often crude, or the pictures and metaphors, always so

deliciously unexpected, as the sequence of the words and syllables, and the

cadence they create, which produces an effect on one’s sensibilities very

closely akin to that of music.[72]

Of course, it would be too easy to draw

a parallel between a brick in architecture and a syllable (or the smallest

metric unit) in music, all the more that it has already been drawn by the

composer himself in the passage about Svadebka above. Nevertheless, such a

parallel would miss one particular aspect that is absent from the architectural

analogy - namely, semantics and, as a constituent, the correct accentuation and

the rule of prosody.

Let

us recall the “linear perspective of Japanese declamation.” The reflections of

Druskin, who treated the topic in detail,[73]

suggest that the young composer probably intended to compare the absence of

tonic accents in Japanese to the flat two-dimensional perspective,

characteristic of Medieval paintings up until the middle of the 15th

century and resurrected in the 20th century under the influence of

non-European art by Paul Gauguin and Henri Matisse (rather than to the normal

three-dimensional perspective of the Renaissance, commonly called “linear”).[74]

However, unlike the contemporary cubist painters, the composer of Trois lyriques japonaises did not yet

intend to overthrow the existing canon, but to reproduce the natural similarity

of the first impression from these poems to the impression of two-dimensional

Japanese graphic art:

In the summer I had read a little anthology of Japanese

lyrics - short poems of a few lines each, selected from the old poets. The

impression which they made on me was exactly like that made by Japanese

painting and engravings. The graphic solution of problems of perspective and

space shown by their art incited me to find something analogous in music.

Nothing could have lent itself better to this than the Russian version of the

Japanese poems, owing to the well-known fact that Russian verse allows the tonic

accent only. I gave myself up to the task, and succeeded by a metrical and

rhythmic process too complex to be explained here.[75]

The composer was able to reflect

symbolically the absence of tonic accents in the Japanese language by

re-accentuating the vocal part. In order to align accented syllables of the

text with metric upbeats of the music, the vocal part was displaced

approximately one crotchet ahead of the accompaniment, and so an ambiguity of

not only “linear perspective” but also of the meaning of the words was created.

Later

in his life, when the interplay of musical and textual accents would become, so

to say, a “visiting card” of the composer’s mature style, there were frequent

incidents of misunderstanding, complaint, and frustration - either from critics

and colleagues (such as Myaskovsky) or directly from the librettists. André

Gide, for instance, explained his absence from the premiere of Perséphone as

follows:

The very night [of the premiere], throwing the whole

thing up in disgust, I left for

Says Craft

regarding Perséphone’s reception and Stravinsky’s attitude to text-setting in

general:

Of all composers, Stravinsky - the supreme inventor of

rhythmic structures, of changing meters, of asymmetrical phrase lengths, and,

at another extreme, of rhythmic repetition (the ostinato) - was the one most

fascinated by the exploitation of verse rhythms in music. What puzzles the

listener in Perséphone is, on the one hand, the composer’s acceptance of a text

written in rigidly fixed quantities, which he frequently follows, and, on the

other, his no less frequent disregard of the spoken verbal requirements of

accentuation and stress. Stravinsky’s argument was that to duplicate verbal

rhythms in music would be dull; but the conflict that sometimes arises in his

treatment of syllables as independent sounds, rather than as components of

words, continues to disconcert part of his audience. Prose might have suited him better,

except that ‘En vérité, il n’y a pas de prose… Toutes les fois qu’il y a effort

au style, il y a versification’ (Mallarmé).[77]

Perséphone was the first full-scale

experience of French text-setting (notwithstanding the two Verlaine songs

written in 1910). Being attracted to the Alexandrines in the first place -

sometimes he sketched directly on the poetic text, as he also did for his Russian

vocal works[78]

- Stravinsky became increasingly annoyed with Gide’s directives that concerned

not only the French prosody but also the desired musical setting (“outburst of

laughter in the orchestra” and so on). In his turn, the composer disregarded Gide’s

warning that, above all, the words should be comprehensible to the audience:

There are at least two explanations of Gide’s dislike of my

Perséphone music. One is that the musical accentuation of the text surprised

and displeased him, though he had been warned in advance that I would stretch

and stress and otherwise ‘treat’[79]

French as I had Russian, and though he understood my ideal text to be syllable

poems, the haiku of Basho and Buson, for example, in which the words do not

impose strong tonic accentuation of their own.[80]

Another

explanation is that Gide had little interest in vocal music and text-setting in

general, thinking rather naively that his text would have already provided the

composer with a close approximation of the musical rhythm.[81]

The very fact of collaboration with Gide on the libretto of Perséphone was

rejected by the late Stravinsky,[82]

whereas the cooperation with W. H. Auden (1909-1973) on the libretto of The

Rake’s Progress (1947) was remembered as one of the most intellectually

enriching experiences of his life:

Auden fascinated and delighted me more every day. When we

were not working he would explain verse forms to me, and almost as quickly as

he could write, compose examples; I still have a specimen sestina and some

light verse that he scribbled off for my wife; and any technical question, of

versification, for example, put him in a passion; he was even eloquent on such

matters.[83]

Wystan had a genius in operatic wording. His lines were

always the right length for singing and his words the right ones to sustain

musical emphasis. A musical speed was generally suggested by the character and

succession of the words, but it was only a useful indication, never a

limitation. Best of all for a composer, the rhythmic values of the verse could

be altered in singing without destroying the verse. At least, Wystan has never

complained. At a different level, as soon as we began to work together I

discovered that we shared the same views not only about opera, but also of the

nature of the Beautiful and the Good. Thus, our opera is indeed, and in the

highest sense, a collaboration.[84]

Apart

from Auden’s receptiveness to re-accentuation and his readiness to make changes

to suit the music,[85]

the English language also gave Stravinsky more flexibility of accent than

French. Nonetheless, after the first performances of the opera in

English-speaking countries, the composer was blamed repeatedly for his insensitivity

to the language.[86]

The fact that he did not speak that language fluently enough cannot be given as

an excuse, for both Auden and Robert Craft were already at his disposal to mark

the accents (which they did). As his sketches for The Rake’s Progress

demonstrate,[87]

at times Stravinsky changed deliberately correct scansion into incorrect,

balancing up rather tactfully the artificial and the natural,[88]

and at other times he simply added a new text to the existing music - the

practice he favoured beginning from Bayka.[89]

In

his late vocal works written in the 1950s and 60s, there is a further move

towards the so-called “reversed” perspective of text-setting, combined with a

more scrupulous approach to dramaturgy.[90]

In these text-settings Stravinsky distanced himself more and more from the

every-day language. In doing this, the composer undoubtedly took into account

the “ignorance” factor, that is, the fact that his (mostly American) audiences

would be unfamiliar with the historical English or Biblical Latin (or Hebrew,

for that matter), which would force them to pay more attention to the music.

His practice of further abstracting syllables from words reached a pinnacle in

the serial work Threni, where capital Hebraic letters (Aleph, Beth, He, Caph,

Res) were set to music.[91]

Still, the accent-fluctuating and word-painting technique B la russe continued

well into the late period.[92]

Zinar brings up a very interesting point, based on her analysis of Stravinsky’s

settings of Latin (Oedipus Rex, Symphony of Psalms, Threni, Canticum Sacrum).

While the composer considered music “by its very nature, essentially powerless

to express anything at all,”[93]

he repeatedly took the opportunity to word-paint with all harmonic, melodic,

dynamic, and rhythmic means available to him, being equally concerned “with the

expression of the thoughts, moods, and words of the text.”[94]

In

the case of Russian-language works of the Swiss years, however, the strict

observance of the rule of prosody co-exists peacefully and alternates with a

few deliberate violations thereof. The balance was found in 1916, in the course

of the composer’s collaboration with C.-F. Ramuz on the translation of Bayka.

It was real fifty-fifty team-work, as seen in the following paragraph from

Ramuz’s Souvenirs sur Igor Stravinsky (1928):

Stravinsky read me the Russian text verse by verse, taking

care each time to count the number of syllables in each verse, which I would

write down in the margins of my paper; then we made the translation, that is,

Stravinsky translated the text for me word for word. It was word-for-word so

literal as to be often quite incomprehensible, but with an inspired (non-logical)

imagery, meetings of sound whose freshness was all the greater for lacking any

(logical) sense… I wrote down my word-for-word; then came the question of

lengths (of longs and shorts), also the question of vowels (this note was

composed to an o, that one to an a, that one to an i); finally, and most

important of all, the famous and insoluble question of tonic accent and its

coincidence or non-coincidence with the musical accent. Continual coincidence

is too boring; it only satisfies our sense of rhythm and measure. But it would

totally contradict the inner essence of the music which was first sung to me,

then played on the piano with an accompaniment of cymbals, then sung and acted

out at the same time – the music that was coming to me alive. To obey the rules

meant to betray the inner essence of this music. To go against the rules at all

costs meant to turn the logic inside out, which would be no less deceitful and

no less tedious.[95]

Later

in life, Stravinsky would return to the same question in his conversation with

Craft about “subtle parallelisms”:

RC – I have often heard you say ‘an artist must avoid

symmetry but he may construct in parallelisms.’ What do you mean?

IS – The mosaics at Torcello of the Last Judgment are a good

example. Their subject is division, division, moreover, into two halves

suggesting equal halves. But, in fact, each is the other’s complement, not its

equal nor its mirror, and the dividing line itself is not a perfect

perpendicular… Mondrian’s Blue FaHade (composition 9, 1914) is a nearer example

of what I mean. It is composed of elements that tend to symmetry in subtle

parallelisms.[96]

Druskin, the editor and commentator of

the Soviet omnibus edition of the dialogues with Craft, draws attention to the similarity

of “subtle parallelisms” to the concept of “dynamic calm” from chapter 2 of

Poétique musicale.[97]

Both ideas should be understood in the context of the division of all music

into chronometric (coinciding with the normal psychological experiencing of

time) and chronoametric (emotionally charged, sharply contrasting, “Dionysian”)

as described in an article by Stravinsky’s close friend Pierre Souvtchinsky.[98]

The “dynamic calm” is what one experiences while listening to the music of the

first, “Apollonian” kind. Although for Stravinsky the composer striving for

unity is fundamentally more important and always precedes plunging into

contrast, “the coexistence of the two is constantly necessary, and all the

problems of art… revolve ineluctably about this question.”[99]

No

doubt, the precursors of these concepts were discussed with Ramuz who should be

credited with half-opening the door to their creative method “in the making.”

Gordon argues (1983: 218) that the close interaction between the writer and the

composer resulted not only in a list of greater and lesser works, but, much

more importantly, in “a mutually evolving aesthetic.” Ramuz’s receptivity to

Russian folk verse was, in fact, an interest of a professional novelist with a

university degree in literature. In October 1913, following a personal crisis,

Ramuz made a pilgrimage to Aix-de-Provence, Cézanne’s native land, a trip that

made him abandon Paris for his native rural Switzerland in 1914. In the summer

of 1915, he was introduced by Ansermet to Stravinsky who, seeking the links to

his own native soil in folk poetry, “succumbed to the contagion of Ramuz’s

affection and, at least temporarily, adopted the Vaud countryside as his own.”[100]

The writer’s newly-found aspiration to “paint with simple words” so as to free

himself from the shackles of conventionality, abstraction, and discursive logic

was a fertilized soil into which Stravinsky’s seed of the “rejoicing discovery”

was dropped.[101]

One year later (1916) the collaboration began. The writer’s and the composer’s

daily efforts on putting together the French versions of Renard, Les Noces,

Pribaoutki, Berceuses du chat, Souvenirs de mon enfance, Trois histoires pour

enfants, Quatre chants russes, and the libretto of Histoire du soldat led to an

intimate friendship which would long be the object of the most cherished

recollections for both.[102]

Later in his life, Stravinsky would deny the linguistic accuracy and the

artistic quality of these translations, as evidenced by his letter to the Concerts

Catalonia, which had invited him in 1929 to conduct Svadebka:

I do not like to hear Les Noces in French: too different

from the prosody of the original… In my view, the French translation… does not

render the character of the rhythmic accentuation which constitutes the basis

of the Russian chant of this work.[103]

The

translation of Bayka was also attacked impartially in Conversations with Igor

Stravinsky:

However,

back in 1916, the composer was rather pleased with the final product of his

association with Ramuz (see below an excerpt from his letter to the Princess de

Polignac, dated October 5, 1916), and he spoke favourably in Chroniques de ma

vie of the ability of his Vaudois friend to grasp the essence of a language

that was totally unknown to him:

I saw a great deal of Ramuz at this time, as we were

working together at the French translation of the Russian text of my Pribaoutki, Berceuse du chat and Renard.

I initiated him into the peculiarities and subtle shades of the Russian

language, and the difficulties presented by its tonic accent. I was astonished

at his insight, his intuitive ability, and his gift for transferring the spirit

and poesy of the Russian folk-poems to a language so remote and different as

French.[105]

Enclosed is

the finished translation of Renard, which M. C.-F. Ramuz made at my request…

This [translation] was a considerable

task, much more difficult than I had thought it would be; I insisted that the French text preserve the flavor of

the original, without [sounding] translated… I think that we have been successful in this task, which we

did together (of course, I participated only whenmusical questions arose)… Let

me assure you, besides, that Ramuz’s translation is not only the best that I

know but is very close to the original as well.[106]

The

last part of the last sentence should not be taken too literally, as no

translation in general (and of poetry in particular, let alone of poetry

already set to music) can do without divergences from the original. Meylan

points to several specific places in Ramuz’s translation of Les Noces, Renard, and chansons russes,[107]

concluding that lyric passages of the folk sources on the whole turned out

“amazingly well,” whereas certain images of Russian folklore, evocative for a

native speaker (e.g., of a nightingale who sings all night long), were omitted from the French version “for

the sake of rhythm.” It should be remembered, however, that the composer could

be held equally responsible for these imperfections.

Overall,

it is possible to hypothesize that Stravinsky, although not a linguist, grasped

(as did Ramuz in his turn) the intricate structure of Russian folk poetry and

the logic of Russian folk accentuation so

intuitively that he

was able to

reproduce them in his vocal works. It is important to remind ourselves

that in these works the composer is still quite remote from the artificiality

of prosody, typical in his settings of Latin, French, or English. In these

works, “linear” and “reversed” perspectives of Russian declamation (that is,

literary and folk accentuation) are combined practically in the same proportion

that is found in Russian folk verse. His main companion on this journey was

(together with Ramuz, of course) his native language that allowed such

experiments - the language that is both rich and flexible, lexically,

semantically, phonologically, and rhythmically. Lastly, Stravinsky’s admirable

sensibility to his native language at the time he was equally distant both from

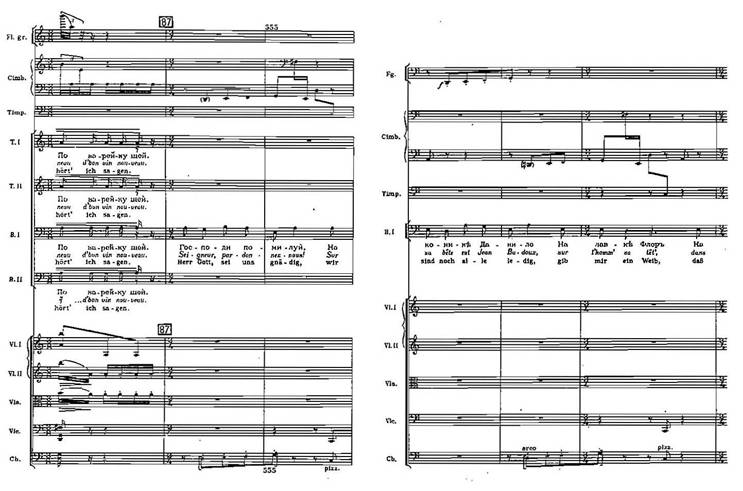

Example 3: Renard

Rehearsal Number 87