Figure 1: Harmonic

Voice-Leading Reduction of mm. 92-102 of Pelléas

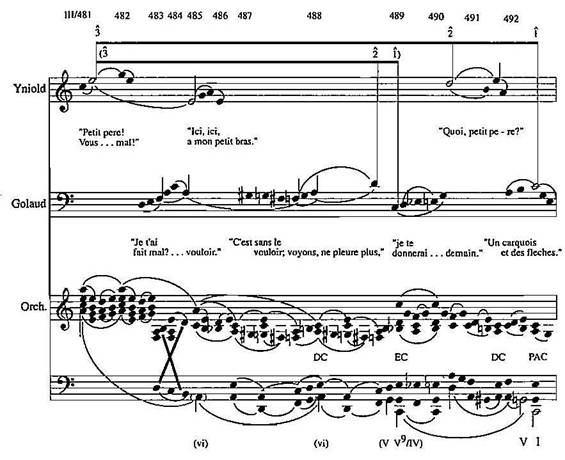

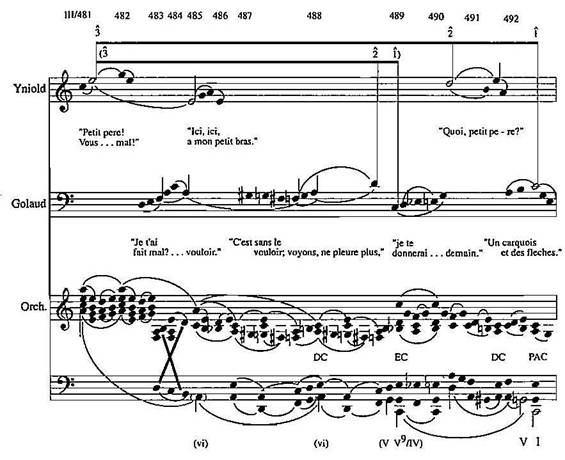

Figure 2: Harmonic

Voice-Leading Reduction of mm. 481-492 of Pelléas

Reuniting the Muses: Cross-Disciplinary

Analysis of Debussy’s Pelléas

and Prélude à “L’après midi d’un faune “

Edward D. Latham

In the pursuit of

interdisciplinary analytical schema, the presence of language itself in the act

of analysis would seem to inevitably privilege poetics, literary criticism,

semiotics, and linguistic philosophy.[1]

This has led analysts to overlook the vital insights offered by the disciplines

most integral to the creation (and recreation) of multi-dimensional works of art, particularly in opera and

ballet studies where theories of dance and drama are rarely brought to the

interpretive table. This essay will attempt to “reunite the muses” by examining

theories developed by two of the most influential performing artists of the

past century - Konstantin Stanislavsky (1863-1938), the Russian actor,

director, and co-founder of the Moscow Art Theatre, and Rudolf von Laban

(1879-1958), the Hungarian-born choreographer and dance theorist - with regard

to their definition of dramatic and gestural closure in opera and ballet,

respectively. Analyses of excerpts from two works by Debussy, the opera Pelléas

et Mélisande and the ballet Prélude à ‘L’après-midi d’un faune’

[Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun], will exemplify the ways in which the

theories of Stanislavsky and Laban can fundamentally alter the interpretation

of opera and ballet, both for the analyst and for the performer.

Closure as

an Inter-artistic Construct

In his

study of parallelism in the arts, the aesthetician James Merriman notes that in

order to compare features of music and drama those features must be possible in

both mediums. He lists repetition, contrast, reversal, juxtaposition, and

heterogeneity as potentially analyzable features.[2]

If one were to distill Stanislavsky’s system of dramatic objectives down to a

single feature, however, that feature would be closure. A character’s dramatic

success is defined by the attainment of local objectives, main objectives, and

a superobjective, and the attainment of each objective represents a kind of

dramatic closure, a closing of a chapter in the character’s history. Obviously,

though its definition varies depending on stylistic context, closure is also a

prominent feature of music, and therefore it meets Merriman’s basic requirement

for analysis.

Stanislavsky

defined an objective as ‘the goal of a character’; the actions of the

characters in a play are therefore motivated by their desire to achieve their

objectives.[3]

In order to arrive at a complete understanding of the role he or she is to

play, the actor must undertake what Stanislavsky referred to as ‘the scoring of

the role’, a process during which objectives are identified and refined.[4]

To begin with, the role is divided hierarchically into units of varying length:

the entire role, its various scenes and their subsections, and the individual

lines themselves. Each unit is then assigned an objective: Stanislavsky used

the term ‘superobjective’ to describe the character’s overarching goal for the

entire play and identified the character’s objectives for each scene as ‘main

objectives’.[5]

The score of a role is typically constructed in the form of an outline, with

the superobjective at the top, main objectives as the section headings, and

line-by-line objectives as subheadings. Because the proceeding analyses address

only local moments in Debussy’s works, complete outlines of character objectives

will be eschewed, though they can be inferred from the ensuing commentary.

Closure in

Pelléas et Mélisande

Though

large sections of Debussy’s score are given over to non-functional triadic

harmony, as well as to the octatonic, chromatic, and whole-tone pitch

collections, he employs isolated instances of linear tonality to amplify or

undercut points of dramatic closure or lack of closure. These moments generally

involve one of three different types of dramatic situations, which might be

called ‘positive’, ‘negative’ and ‘ironic’ situations, each differentiated by a

unique relationship between the vocal line and the orchestra. In a ’positive’

situation, a character achieves a main objective, and both the orchestra and

the vocal line close to the tonic. In a ‘negative’ situation, a character

forfeits a main objective, and neither the orchestra nor the vocal line

achieves closure, despite the expectations created by the establishment of

tonality. ‘ironic’ situations, in which a character mistakenly believes an

objective to be achieved, contain closure in the vocal line, indicating the

character’s misconception, but an evasion of the tonic in the orchestra, either

by means of a deceptive cadence or an evaded cadence in which the subsequent

measures destabilize the tonic.

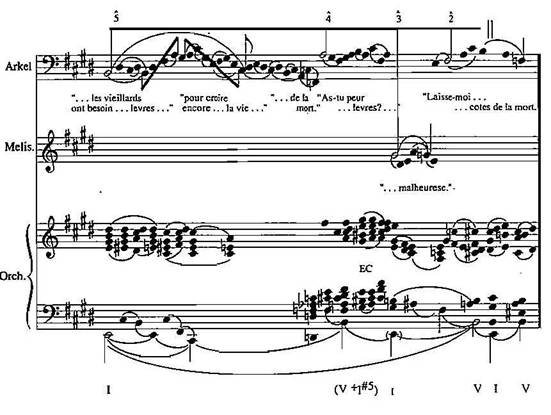

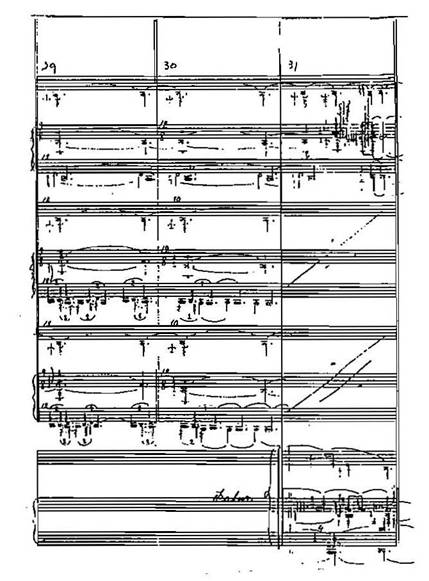

‘Positive’

situations are the most prevalent in Pelléas, and two examples are given

in Figures 1 and 2. In the passage shown in Figure 1, from Act II, Scene 1,

Mélisande’s objective is to convince Pelléas that the wedding ring given to her

by Golaud, which has ‘accidentally’ fallen into a well, is not worth

retrieving. Achieving this objective will help her to attain her main

objective, which is to free herself from Golaud. She persuades Pelléas by

telling him it is too far away, rippling the water so that the ring can no

longer be seen, and then declaring that he was mistaken in saying he had seen

it in the first place.

Debussy

sets this moment as a 5-line in F major, with the fundamental descent taking

place in Mélisande’s vocal line. The passage begins with a progression in mm.

92 to 93 that defines a first-inversion. F-major triad as tonic. The key is

defined in a faintly mysterious way, however, due to the B natural in m. 92

that precludes the presence of the key-defining tritone, E-flat. Scale-degree

5 (C) is instituted as the primary tone in Mélisande’s vocal line on the word

‘loin’ [far] in ‘Elle est si loin de nous’ [it is so far from us], and is

immediately decorated by an upper neighbor D. The orchestra moves to the

dominant at the end of m. 94 to provide the harmonic context for the subsequent

E half-diminished seventh chord, which becomes an extension of the dominant.

Scale-degree 4 (B FLAT), is established in the melody at ‘Non, non, ce n’est

pas elle’ [No, no, that its not it], and is prolonged through the unfolding of

the tritone, B flat to E.

Figure 1: Harmonic

Voice-Leading Reduction of mm. 92-102 of Pelléas

Figure 2: Harmonic

Voice-Leading Reduction of mm. 481-492 of Pelléas

At the

arrival of scale-degree 3 in m. 96, the orchestra returns to the tonic, this

time in unequivocal root position, and plays a transposition of the theme from

mm. 92-93. In this way, the original harmonic ambiguity of the opening phrase

is clarified. After a prolongation involving a consonant skip up to C in the

melody, accompanied by a voice exchange in the orchestra at mm. 96 to 97,

Mélisande returns to scale-degree 3, decorated by a double neighbor, at m. 99.

The manner in which Debussy finishes the passage, with a strikingly accented

chromatic descending-thirds progression followed by a brief, matter-of-fact

descending-fifths progression, makes Mélisande’s question - ‘Qu’allons nous

faire maintenant?’ [What will we do now?] - a rhetorical one. She does not

intend to do anything about the lost ring; in fact, she meant to lose it.

The

analysis of this brief excerpt is additionally enriched by the presence of

numerous foreground motives, both melodic and harmonic, that act as indicators

of the characters’ local line objectives. In Figure 1, for example, the

dominant ninth, a symbol of desire throughout the opera, appears at m. 94, as

Mélisande ripples the water, making the ring disappear. Moreover, Mélisande’s

primary harmonic motive, F major, is the key of the excerpt, demonstrating her

control of the situation, though Golaud’s motive lurks in the alternating

major-seconds in the opening theme of the passage and its subsequent transposition.

Figure 2

shows a passage from Act III, Scene 4. In this scene, Golaud, whose

superobjective is to keep Mélisande’s heart captive, is trying to persuade

Yniold to tell him what he knows about the relationship between Pelléas and

Mélisande. The attainment of this main objective will permit him to separate

the two would-be lovers, thus bringing him closer to his superobjective. The

excerpt begins with a prolongation of E, presented in Yniold’s melody at ‘Petit

père! Vous m’avez fait mal!’ [Daddy! You have hurt me!], and it is E that may

be identified retrospectively as the primary tone, scale-degree 3 in C major.

At m. 485, E is coupled in the lower octave in Yniold’s melody at ‘Ici, ici, a

mon petit bras’ [Here, here on my little arm]. Up to this point, the passage

has projected an ambiguous sense of key: mm. 481 to 482 project A minor by

sounding an A-minor triad on each downbeat and surrounding each of them with

a i-v-(iv6)-v6

progression, but the lack of a leading-tone G# leaves open the possibility for

reinterpretation in C major.

Measures

483 to 484, where the orchestra has a voice exchange that prolongs a B

half-diminished seventh chord, begin to hint at C major, and the tension

between the two keys is exploited by Debussy at m. 487, where he uses a

rhythmic figure in the orchestra that recalls the harmonic progression from mm.

481 to 482. But now the progression sounds as though it is leading to a cadence

in C major via the progression vi-II9-IV-V9. However, the

April 12, 2006repetition at m. 488 of the same one-measure harmonic pattern

places another A-minor triad on the downbeat, creating a deceptive cadence in C

major. Debussy continues his cadential play in m. 489, where, after the same

preparation, he puts a secondary dominant, [V9]® IV, on the downbeat,

evading the cadence and pushing the line forward to a second deceptive cadence

at m. 491 and finally to the perfect authentic cadence at m. 492.

Debussy’s

avoidance of closure to the tonic emphasizes Golaud’s failure to get Yniold to

cooperate. Golaud begins by apologizing for hurting Yniold’s arm, but this only

leads to the deceptive cadence at m. 488. He then tries ordering Yniold to stop

crying, but the evaded cadence at m. 489 shows Yniold has not been won over.

Finally, he bribes Yniold with the promise of a bow and quiver - not exactly

the perfect gift for a cherub between two would-be lovers! Yniold is clever,

though: he demands to know what the bribe will be before offering any

information and Golaud is required to make a concrete offer, hence the second

deceptive cadence before closure to the tonic.

The linear

continuity created by the dialogue between the vocal parts further enhances the

cadential disruptions, particularly the evaded cadence. After Yniold’s initial

prolongation and register transfer of E in mm. 481 to 485, Golaud moves the

fundamental line to scale-degree 2 via a consonant skip from A to D at m. 488.

Thus, when scale-degree 1 arrives over the [V9] ® IV in the next

measure, it sounds more like an evasion because the goal tone has been prepared

in the melody. Yniold sings scale-degree 2 at m. 490, revealing his interest in

the bribe. He picks up the line and moves it forward; Golaud has made progress.

When Golaud takes over the melodic line and provides the final closure to the

tonic, he regains control of the situation.

A

‘negative’ situation is illustrated in Figure 3, an excerpt from Act IV, Scene

2. In this scene, Arkel, Golaud’s grandfather and the king of ‘Allemonde’, wants

to embrace Mélisande. He is unable to achieve this main objective, however,

because his tête-á-tête with Mélisande is interrupted by Golaud. The

passage begins with the initiation of the primary tone B (5 in E major) in

Arkel’s vocal line. After prolonging scale-degree 5 with a skip up to

scale-degree 7 (D#) over a dominant ninth (the symbol of desire again), Arkel

returns to scale-degree 5 over the tonic at m. 165. A pair of unfoldings ensue,

prolonging the primary tone by expanding the upper neighbor C# from Arkel’s

opening motive into a three-measure structure. The vocal line then moves to

scale-degree 4, supported by the dominant, and there is an evaded cadence in

the orchestra as Arkel asks ‘As tu peur de mes vieilles lèvres?’ [Are you

afraid of my old lips?] One can imagine that, just as he is about to kiss her,

Mélisande shrinks away, and the cadence is evaded.

Mélisande

introduces scale-degree 3 over I6 at m. 175. She then embellishes it

with a chromatic pitch, G natural, that is part of an inverted statement of

pitch-class set 3-7 [025], the set-class form of her primary leitmotive. Arkel

will not be deterred from E major, however, and he pushes the line down to F#

(scale-degree 2) over the dominant in m. 179, placing Mélisande’s G natural into

the context of E major as a chromatic passing tone. Scale-degree 2 is prolonged

with an arpeggiation of the supertonic triad in the vocal line, but closure to

the tonic is avoided in both the melody and the accompaniment. Arkel trails off

awkwardly on the same incongruous F natural which set the earlier use of the

word ‘mort’ [death] at m. 169, and the orchestra embellishes the tonic with a

pair of suspensions deriving from Golaud’s motive. The harmony continually

falls back to the dominant ninth, which is eventually reduced to just the two

notes of Golaud’s motive as he enters and interrupts the encounter at mm. 185

to 186.

Figure 3: Harmonic

Voice-Leading Reduction of mm. 203-205 of Pelléas

Figure 4: Harmonic Voice-Leading

Reduction of mm. 388-401 of Pelléas

Figure 4

is an example of an ‘ironic’ situation, in which the protagonist believes an

objective to be achieved, but the omniscient orchestra indicates otherwise.

Figure 4 shows a passage from Act III, Scene 3, in which Golaud and Pelléas,

having just left the catacombs beneath the castle, discuss the rendezvous

between Pelléas and Mélisande at the tower the night before, which Golaud

discovered. Golaud’s main objective in this scene is to shame Pelléas into

staying away from Mélisande.

Beginning

with motion to the dominant in E flat minor, the orchestra supports the

initiation of the primary tone (B flat) in Golaud’s melody at the word ‘soir’

[night]. The harmonization of scale-degree 5 with the dominant instead of the

tonic emphasizes the rough discontinuity of Golaud’s change of subject.

Impatient with Pelléas’s inability to comprehend the meaning of his subtle

threats and intimations in the previous scene, Golaud cuts right to the chase,

without bothering to establish an E-flat minor tonic first. Golaud leaves no

doubt about his goal, however, when his line arpeggiates the tonic triad at m.

391, and the orchestra affirms the tonic by entering on Eb in the next

beat.

Harmony,

line, and motive are merged beautifully at mm. 393-394, when scale-degree 4,

played by the orchestra and echoed by Golaud, is harmonized by a four-part

setting of Mélisande’s symmetrical 3-7 motive in the orchestra, at its original

transpositional level (the harmonic progression is II-V-VII-V-II). The

orchestra then moves to the submediant (acting as a tonic substitute) at m.

396, to support scale-degree 3 in Golaud’s melody. In the following measure,

Golaud’s impatience leads him to move to scale-degree 2 several measures too

soon, rather than over the structural dominant. Then, in a violent outburst, he

leaps away from scale-degree 2, reaching up to D flat, his highest note in the

passage. Music theorist Walter Everett has described events like this one as

moments where a character’s excesses of emotion cause him to override the

linear progression of the melody, and that is what clearly happens here, as

evidenced by the appearance of Melisande’s motive in Golaud’s melody in mm. 397

to 398.[6]

When the orchestra reasserts scale-degree 2 at m. 400, Golaud, who considers

the matter closed, does not pick up on the cue but instead jumps directly from

scale-degree 5 to the tonic. The orchestra, knowing the truth of the matter,

enters on b7,

creating the effect of a [V42] ® IV with

the sparsest of means, but nonetheless evading harmonic closure.

From

Analysis to Criticism: the Welsh National Opera Pelléas

Stanislavsky

always intended his system to be put to practical use, not to remain solely at the

theoretical level. By highlighting the ways in which Debussy’s score reinforces

or undercuts the characters’ attainment of their objectives, the four analyses

above might be of practical use to directors, conductors, and performers

preparing a production of Pelléas. In order to remain faithful to the

original sprit of Stanislavsky’s work, some of the possible applications of the

knowledge gained from the analyses will now be discussed with regard to two

excerpts from the Welsh National Opera video recording of Pelléas.[7]

The first

excerpt, which corresponds to Figure 1, shows Alison Hagley as Mélisande,

acting thoroughly distraught at the loss of the wedding ring given to her by

Golaud. At the moment where the rapid descending arpeggio is heard in the

orchestra (which I have interpreted as Mélisande’s attempt to hide the ring’s

descent by rippling the water), Hagley makes a somewhat gratuitous cross to

stage right. Even though the conductor, Pierre Boulez, accentuates the

decisive, almost playful nature of the cadence in the orchestra by exaggerating

Debussy’s staccato articulation and slightly increasing the tempo, director

Peter Stein chooses to have Hagley remain genuinely agitated, leaving her

nothing to play but vague emotion. Neill Archer, as Pelléas, however, registers

his understanding of the meaning behind her question ‘What shall we do now?’

His head snaps up and his eyes widen as he replies, ‘You must not worry so

about a ring.’

An

interpretation of the same passage that incorporated an understanding of its

musical and dramatic closure might make Melisande’s reaction more ambiguous. At

the line, ‘Non, non, ce n’est pas elle’ [No, no, that is not it], Melisande

could create a slight accelerando to show her determination, bending

down and rippling the water with her hand. At ‘ce n’est plus elle’ [That is no

longer it], she could place an accent on the word ‘elle’, straightening and

drying her hands on her skirt, as if giving up the search. On her final line,

‘Qu’allons-nous faire maintenant?’ [What will we do now?], she ought to look

directly at Pelleas, slightly clipping the final F natural to make the question

a bit more pointed.

The second

excerpt, which corresponds to Figure 3, presents the opposite problem. Whereas,

in the scene at the well, Stein chose to ignore the tonal closure in both the

orchestra and the vocal line, in Act IV, Scene 1 he does not take into account

the lack of closure in the music. Instead of exploiting the tension

between Arkel’s desire to embrace Mélisande and her desire to avoid the

embrace, Stein permits Arkel not only to kiss Mélisande, both on the forehead

and on the mouth, but also to caress her in a very intimate fashion. Although

Hagley as Mélisande is clearly aware of the implications of Arkel’s request for

her to come closer, since she demurely resists the pull of his arm, Stein’s

interpretation of their encounter makes Golaud’s subsequent arrival over the

unresolved dominant ninth seem less like an interruption than like a guilty

coda - a husband walking in on the lovers the next morning.

Just as

opera directors, conductors, and singers might benefit from the study of

musico-dramatic closure and the lack thereof, choreographers and dancers might

gain valuable insights into the works they create and perform through the use

of ‘linear-gestural’ analysis. The notational system developed by Rudolf von

Laban provides a stable and reliable medium in which to present a dance score

for the kind of detailed study such an analysis would require, and it will therefore

serve as a basis for the remainder of the present study.

Exploring

Closure in Dance Through Labanotation

Rudolf von

Laban was born in 1879 and spent his youth traveling throughout the Austro-Hungarian

Empire with his father, a military governor.[8]

After abandoning the military academy in which his father had pressed him to

enroll, Laban traveled to Paris, familiarizing himself with the early dance

notation system of the eighteenth-century French choreographer Raul-Auger

Feuillet, and studying dance, art and architecture. He later moved to Munich,

Zürich, and, after enduring persecution under the Third Reich, settled in

London. He published ten books on dance, including his Schrifttanz [Written

Dance] of 1928, his most important and influential work, and founded several

dance institutes and organizations. He died in Surrey, England in 1958.

The most

significant accomplishment of Laban, who is to dance theory what Schenker is to

music theory and Stanislavsky is to dramatic theory, was the development of a

comprehensive system for the notation of choreography, which he called

‘kinetography’, or the study of drawing movement. Later, American proponents of

his notational system dubbed it ‘Labanotation’, and it rapidly became the gold

standard of dance notation systems. As structured by Laban, a ‘kinetogram’, or

dance score, is written on a three-line staff adapted from the standard

five-line staff used in musical notation.[9]

The second and fourth lines are omitted for the sake of visual clarity, but the

insertion of the subsequent symbols is carried out with these hidden lines in

mind. The staff is arranged vertically, in order to show forward progression or

momentum, but can be rotated ninety degrees to run parallel to the music, if

necessary.

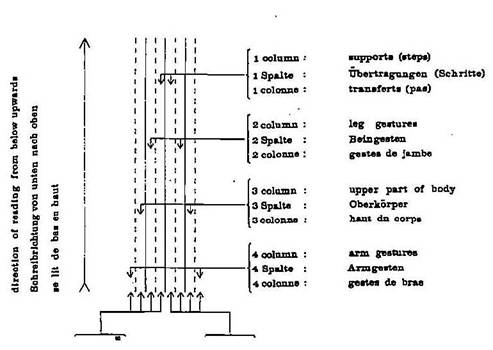

In the

introductory section of his ‘dictionary’ of Labanotation, Albrecht Knust, one

of Laban’s foremost students and collaborators, provides an elegant outline of

the basic aspects of Labanotation. Figures 5 and 6 reproduce excerpts from

Knust’s first two pages of examples. As shown in Figure 5, the center line

divides the dancer’s body into left and right halves, with movements performed

by the right side of the body (that is, the dancer’s right) notated to the

right and vice versa. Leg movements are notated immediately to the right and

left of the center line if they support the weight of the body, as in walking,

and in the next column if they do not, as in a gesture like the tendue

[extension of the leg]. Movements of the upper torso and arms are notated in

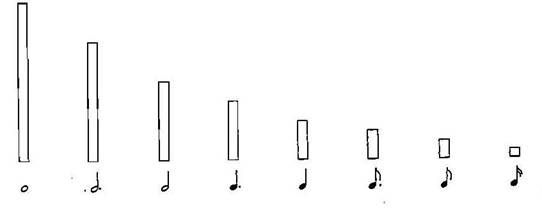

the outer columns. Figure 6 shows the basic symbols for direction and height,

the former indicated by the shape of the symbol (as in the triangle pointing to

the right), and the latter indicated by shading (striated for high, blank with

a dot for medium, and filled for low). The length of a particular symbol on the

staff represents its duration, as shown at the bottom of Figure 6. Figure 7

shows the basic symbols for direction, indicated by the shape of each symbol

(e.g. the triangle pointing to the right). Height is indicated lby shading

(striated for high,blank and a dot for medium and filled for low). The

direction symbols in Figure 7 are shown in the high position.

Although

space limitations prevent an explanation of them here, there are eight other

categories of symbols, in addition to the

direction signs, including position signs, body signs, and relation

signs, among others. Perhaps the most interesting of these are the preliminary

indications, or ‘presigns’ given in the choreographical score before the dance

begins, two categories of which are likened by Knust to the key signature and

clef in musical notation.

Figure 5: The Center

Line of the Body and the Limbs (Knust)

Figure 6: Indicating

Duration of gestures (Knust)

Figure 7: The

Direction Signs (Knust)

Nijinsky

and Dance Notation

One of the

primary purposes of Labanotation is the preservation and reconstruction of historical

choreography, the finer details of which would eventually be lost due to the

vagaries of the oral tradition of passing them from teacher to student. It was

for this purpose that Ann Hutchinson Guest and Claudia Jeschke created their

1991 transcription of the dance score for Debussy’s Prélude à ‘L’après-midi

d’un faune’, as choreographed by Vaslav Nijinsky.[10]

Unlike memory-based Labanotation scores that represent the culmination of an

oral tradition, however, Guest and Jeschke’s score of Faune is a

translation of Nijinsky’s own notated score, which he created in 1915 using a

system he developed himself.

Intriguingly,

Nijinsky’s system, like Schenker’s, borrows elements of musical notation for many

if its symbols (see Figure 8). Duration of gestures, for example, is indicated

using traditional note values on a five-line staff. Based on the Stepanov

system taught to him as a student at the Maryinsky Theater School in Russia,

Nijinksy’s system nevertheless includes some significant improvements,

including the use of a separate staff for each section of the body, the use of

rests for exits and ties to indicate the retention of a particular gesture,

and, perhaps most importantly, the use of ascending or descending ‘pitch’ to

indicate the angle or direction of a gesture.

Because it

is difficult to scan quickly and interpret accurately, however, it is doubtful

that Nijinsky’s system will replace Labanotation as the primary system of dance

notation. Nonetheless, Guest and Jeschke’s research into his score for Faune

reveals a previously hidden aspect of Nijinsky’s professional persona: that of

the theorist and analyst. It is this aspect of Nijinsky that warrants further

investigation with respect to his score for the Prélude.

Closure in

Debussy and Nijinsky’s Score

In

creating his now-famous interpretation of Debussy’s Faune, from which

musical elements did Nijinsky draw his inspiration, and how does his choreography

interact with the music? An examination of ‘L’après-midi d’un faune’, the 1867

eclogue by Stephane Mallarmé to which Debussy’s title makes reference, reveals

only general correspondence between it and Nijinsky’s ballet (i.e., the faun as

central character, his encounter with the nymphs, and the use of grapes); in

its details, the poem differs markedly from the story created by Nijinsky. In

the eclogue, the faun meets only two nymphs, for example, not seven, and his

subsequent ménage-à-trois with them has much more explicit and graphic

sexual overtones than the comparatively innocent narrative portrayed in the

ballet. It is ironic, then, in retrospect, that the ballet, and particularly

its closing scene (where the Faun caresses the dress left behind by his Nymph),

created such an uproar when it was premiered in Paris in 1912.

Figure 8:

Nijinsky’s Notation System

The

disparity between Mallarmé’s and Nijinsky’s versions of the story highlights an

interesting ambiguity in Debussy’s title. Interpreted literally, ‘Prelude to

the Afternoon of a Faun’ could signify music that describes an episode

prefiguring the Faun’s afternoon adventures. Perhaps the Faun, inspired by his

encounter with the Nymphs as portrayed by Nijinsky, returns later to seek them

out, as portrayed by Mallarmé. Yet, it is equally possible that the title is

meant to infer a more direct connection between the music and Mallarmé’s

eclogue, as in ‘music for the afternoon of a faun’. It is to Debussy’s music

and Nijinsky’s choreography that we must turn to give preference to one

interpretation or the other.

As is

often the case with Debussy scholarship, the analytical work that has been done

on the Prelude divides into two camps. On the one hand, there are those, chief

among them Richard Parks, who would claim it is an early work by Debussy the

modernist: they tend to minimize its diatonic elements in favor of its motivic

intervallic structures and chromaticism and generally prefer pitch-class set

theory to tonal theories.[11]

On the other hand, there are those, including Felix Salzer, Charles Burkhart,

and Matthew Brown, who would argue that it is the work of Debussy the late

Romantic: they tend to maximize its diatonic elements, absorbing as much of its

recalcitrant chromaticism as possible with the porous sponge of Schenkerian

theory.[12]

In the case of the Prélude, though, a tonal reading is both appropriate

and compelling. In his zeal to unearth complement relations, 4-17/18/19 complexes,

and other atonal pitch relations, Parks seems to overlook a defining feature of

the Prelude’s musical structure - namely, its restless search for, and drive

toward, the root-position tonic E-major triad that arrives only at m. 106, four

bars from the end of the piece.

The

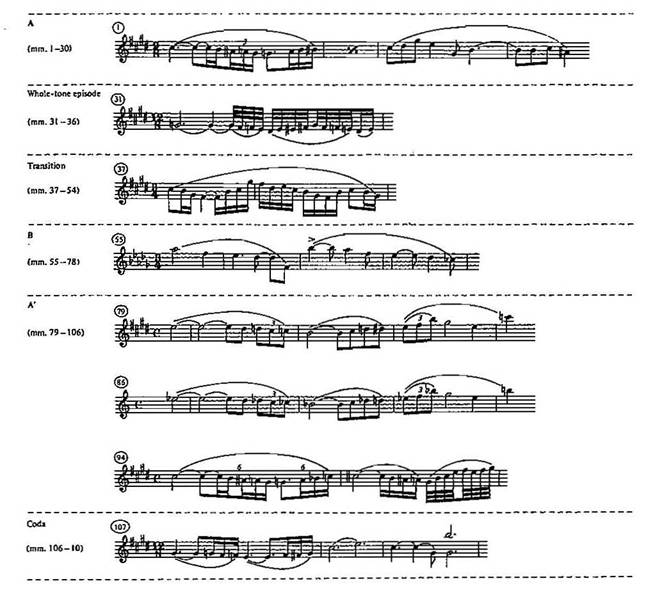

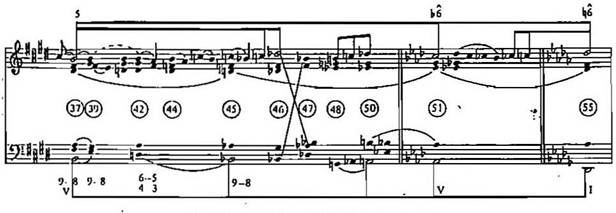

Schenkerian studies of the Prelude are largely in agreement on its broad formal

and harmonic outlines: each of them chooses E major as the work’s tonic key,

and none of them departs radically from the formal plan proposed most recently

by Matthew Brown in 1993 (see Figure 9). They do differ, however, in both the

scope of their analyses and the degree to which they are willing to subsume the

B section of the Prelude (which outlines D flat Major) under an E-major

background structure. Salzer, for example, analyzed only the first thirty

measures of the piece, stopping conveniently short of the first major chromatic

episode in mm. 31-36. Burkhart, too, tackles only a portion of the work (mm.

37-55), though his illustration of the chromatic ascent B-C-D flat as an

enharmonic motivic enlargement of the B-B#-C# ascent of mm. 1-2 lays important

groundwork for Brown’s subsequent analysis of the complete piece.

Matthew

Brown’s analysis is by far the most daring. Not only does he analyze almost

every bar of the Prelude (mm. 14-20 being the notable exception), he accounts

for the thorny chromatic (whole-tone) episode of mm. 31-36 by relating it to

the two occurrences of the structural dominant that surround it in mm. 30 and

37, and he incorporates Burkhart’s B-C-D flat as a transition section to the

secondary key of D flat major. The key to Brown’s analytical success is his

enharmonic reinterpretation of D flat as C#, an upper neighbor to the primary

tone B (scale-degree 5) that becomes part of an expanded 5-6-5 melodic

progression. C# as upper neighbor to B is also the primary focus of Salzer’s

analysis of mm. 1-30, and the two analyses complement each other very well.

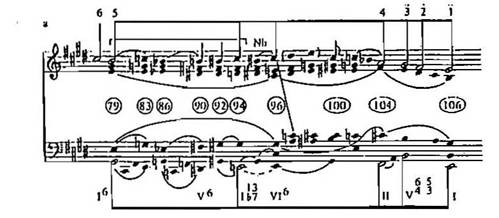

While

Brown’s analysis is convincing in many respects, it contains four major flaws.

First, the 5-line he proposes as a background structure, the entire descent of

which takes place in the span of three measures, contains little harmonic

support for scale-degree 3 (his analysis of mm. 79-106 is reproduced in Figure

10). Though he shows scale-degree 3 as supported by the cadential six-four in

m. 105, a paradigm well documented by David Beach, the B shown in the tenor is

actually an A and a C# in the music, severely weakening the sense of tonic

harmony in the first part of the measure and privileging V9 instead.

Second, Brown does not provide an analysis of mm. 14-20, which mark

the motion G#-A-A#

as a transposed

instance of Burkhart’s ascending

chromatic motive, now in a more prominent register. Third, in his eagerness to

show Burkhart’s motive in its most flattering light, he obscures several

important structural harmonies - notably the E-major tonic.

Figure 9: Prélude à

l’après midi d’un faune, Formal Plan (Brown)

Figure 10: Prélude , mm 79 - 106 (Brown)

Example 1: Prélude à l’après midi d’un faune ,

mm 14 - 20

Figure 11: Prélude , mm 35 - 77 (Brown)

\

An

alternative reading of the Prelude as a 3-line is shown in Figure 12. Like

Brown’s analysis, the reading shown in the figure depends on an enharmonic

transformation: the primary tone G#, prolonged via an upper-neighbor A# in m,

17 and an upper-neighbor A in mm. 23 and 42, becomes Ab at m. 45. Ab is then

prolonged by two middleground descents to F (mm. 45-55 and 63-74), and an

enharmonically re-spelled lower-neighbor Gb (m. 62). The return of the home key at m. 79 brings with

it a prolongation of E, scale-degree 1, via a lower-neighbor Eb, and the eventual

reinstatement of G# as primary tone at m. 94. The fundamental line closes to

the tonic at m. 106.

Figure 12: Prélude , Alternate Analysis as

3-Line

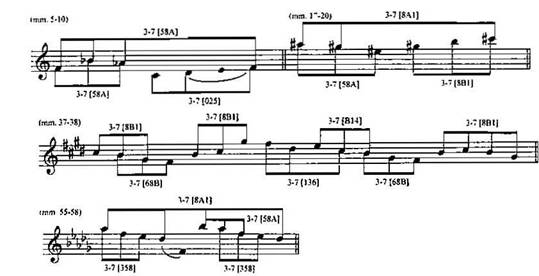

In

addition to accounting for the aurally salient head note of the B-section

theme, the reading shown in Figure 12 incorporates the missing measures 14-20,

which, rather than being merely transitional, constitute an important

prefiguration of both the “bathing” theme at m. 37 and the B-section theme at

m. 55. As shown in Figure 13, these three themes are connected to the opening

measure of the Prélude, and to each other, through their prominent use

of pitch-class set 3-7 [025], the set-class form of Mélisande’s motive. The

dates of composition for the opera and the ballet overlap: Debussy began

working on Pelléas et Mélisande in September, 1893 and had finished a

complete draft by August 1895; the Prélude was begun in 1891, and

premiered in December 1894. Set-class 3-7, then, along with set-classes 4-27

and 5-34, both used extensively in Pelléas to signify Golaud’s passion

for Mélisande, can be seen as intertextual symbols of desire, resonating in

both works.

In

Nijinsky’s setting of the Prélude, the erotic connotations of 3-7 and

4-27 are made explicit. Whereas for the majority of the opening A section the Faun

mimes playing the flute theme onstage, when 4-27, the A# half-diminished

seventh chord, is arpeggiated in mm. 4 and 7 he stops and turns to look

offstage, as if checking to see whether his sinuous melody has borne fruit. His

longing is expressed in the subsequent arpeggiation of 3-7 as part of the B

flat dominant seventh chord in mm. 8-10, as he slowly returns to his original

posture. Again, in mm. 14-20, as 3-7 returns in the melody, he puts down the

flute, and picks up some grapes as if to devour them: Example 2 (on pg. 42)

shows the movement of his arms in the outer columns as he picks up the grapes.

Figure 13:

Set-class

3-7 [025] (Mélisande/Nymph Motive)

For the

most part, the divisions in Nijinsky’s plot correlate with the large-scale

formal divisions proposed by Brown (refer back to Figure 9): the Faun begins

alone on stage, and is joined by the Nymphs in mm. 21-28. The whole-tone

episode in mm. 31-36 creates an appropriately mysterious and exotic atmosphere

for the unveiling of the head Nymph, who begins bathing at m. 37. The

encounter, and subsequent pas de deux, between the Faun and the head

Nymph takes place during the B section, mm. 55ff, and the Faun returns to his

rock alone during the A’ section, at m. 94.

What is

not shown in Brown’s formal scheme, however, is Nijinsky’s response to the

cadential evasions in the B section. Though it begins in Db Major, the B Section

soon moves to V9 of E major at m. 60. Resolution to the tonic is

evaded, however, by a motion to iv64, an A-minor

chord in second inversion, at m. 61, which coincides with the head Nymph’s

first rejection of the Faun’s advances. The Faun then leaps into the air in m.

62, beckoning to her again as the harmony shifts to V9 of G major

(see Example 3). As this new dominant ninth, enharmonically reinterpreted as

being built on an E double flat dominant ninth, again evades resolution by

moving down by step to a Db-major

triad, the Nymph rejects the faun again. The culmination of their battle of

wills occurs in m. 73, where they finally embrace by linking elbows (see

Example 4). It is important to emphasize that Nijinsky chooses not to have

their union occur on the resolution to the Db-major tonic in m. 74. Instead, he acknowledges the

unfinished, interrupted nature of their encounter - the other Nymphs enter,

Donna Elvira-like, and spoil the Faun’s fun - by breaking the embrace at m. 74. Frustrated, the Faun gestures defiantly

at the Nymphs and moves away from the head Nymph. The three stages of the

encounter are shown in Illustration 1, a series of photographs of Nijinksy in

the leading tole taken by Baron Adolf de Meyer soon after the premiere in 1912.[13]

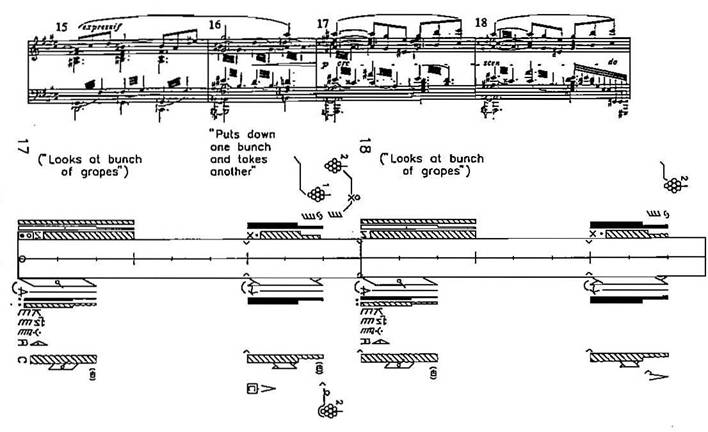

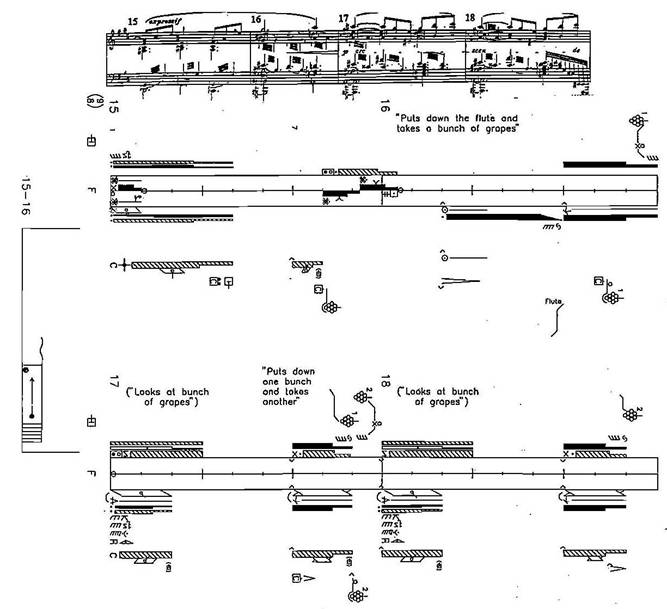

Example 2: Faun Picks

up Grapes (mm. 15-18)

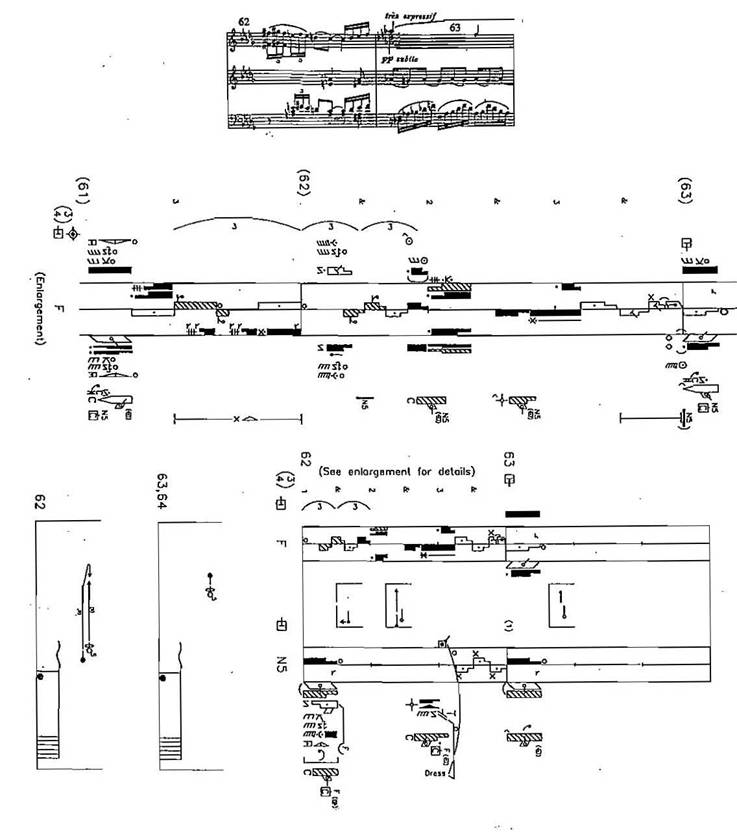

Example 3:

Faun

Leaps into Air (mm. 61-63)

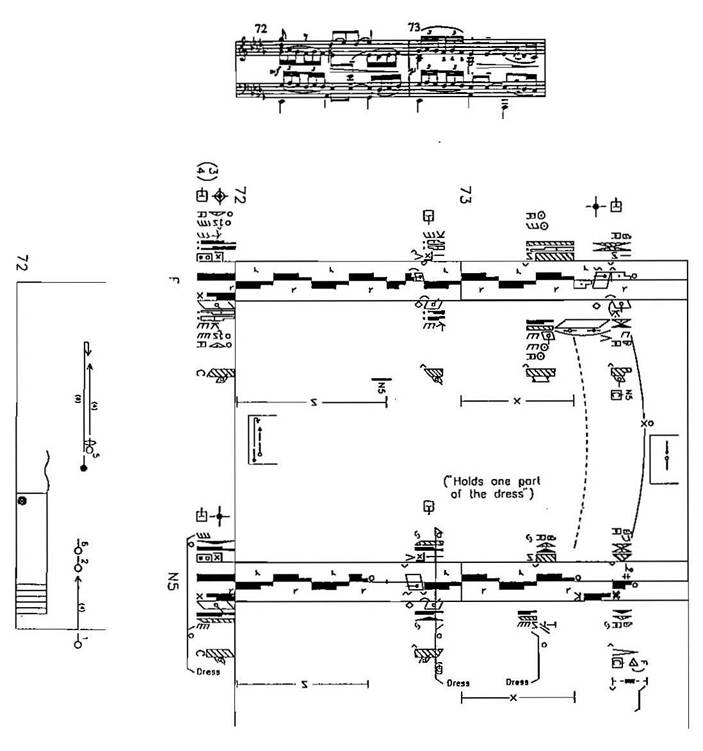

Example 4: Faun and

Nymph Embrace (mm. 72 - 73)

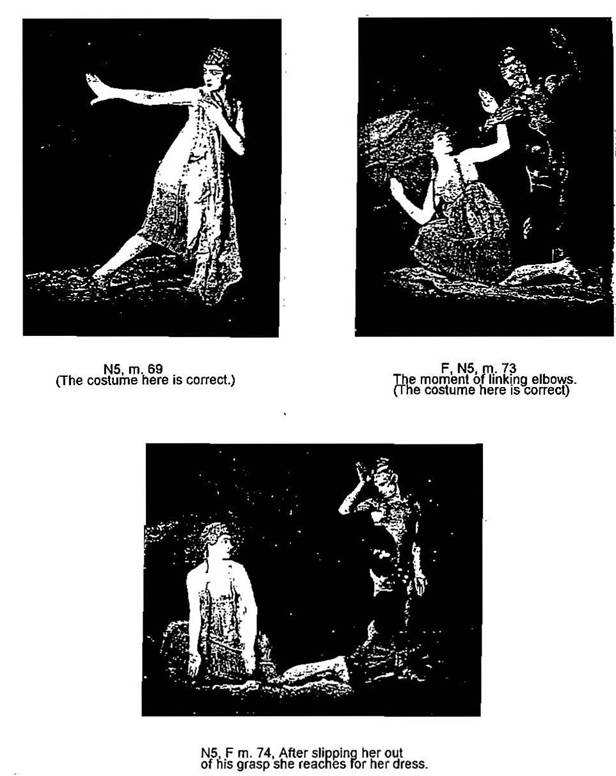

Illustration

1: Nijinsky

in the Title Role (from Guest and Jeschke, 80).

Conclusion

By

constantly returning to the music’s dramatic underpinnings and to the actual

experiences of the characters involved in the scenes discussed, the close

readings presented here aim to provide relevant and compelling interpretations

that will affect audience members and performers alike. Though equal to

Schenkerian analysis in the richness and sophistication of their descriptions

of dramatic and gestural processes, the theories of Stanislavsky and Laban

discussed here remain relatively unencumbered by detailed technical vocabularies

of their own, enabling the analyst simply to redefine and broaden concepts like

closure. Care must be taken, however, at the conceptual level to avoid the

unduly reverential application of models from other disciplines that leads not

to integration but further separation of the constituent disciplines. That

tendency is counterbalanced in the case of the Pelléas analyses through

the inclusion of Type III (ironic) relationships that disrupt the 1:1

correlation of musical and dramatic closure, whereas in the Faune

analyses Laban’s system was not directly involved in the interpretive process.

Because Laban’s system is purely notational, it is value-neutral: its purpose

is merely to create a highly detailed and accurate score for subsequent

performances.

The

interpretations offered here strive to respond to Lawrence Kramer’s charge

that, despite musicology’s evolution in recent years toward a more

interdisciplinary perspective, particularly through the incorporation of

critical theory, little change has been effected in the concept of music

itself. [14]

Although he is right to claim that ‘the music itself’, what Jean-Jacques

Nattiez has called the ‘neutral level’, continues to exist as an independent

and powerful force in analysis and criticism, readings like those presented

here challenge one of its most basic assumptions: the notion that closure,

completeness, and organicism are the most desirable states for a musical

entity. In an multidimensional artwork such as an opera or ballet, the moments

of greatest significance to an audience are often those that reveal

discontinuities, conflicts, or disruptions that generate tension and require

subsequent resolution or cancellation. These moments are Kramer’s hermeneutic

‘windows’, opening onto vistas of unexplored interpretive possibilities.[15]

1 The application of concepts from semiotics and literary criticism to the study of music has produced some of the most well-known music theoretical works of the past thirty years, including works by Fred Lehrdahl and Ray Jackendoff, Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Robert Hatten, Joseph N. Straus and Kevin Korsyn.

2 James D. Merriman, ‘The Parallel of the Arts: Some Misgivings and a Faint Affirmation,’ The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 31 (1972): 155-61.

3 Konstantin Stanislavsky, Creating A Role, trans. Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood (New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1961), 78.

4 Ibid., 56. See also Konstantin Stanislavsky, Stanislavsky’s Legacy: A Collection of Comments on a Variety of Aspects of an Actor’s Life and Art, ed. and trans. Elizabeth Reynolds Hapgood (New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1958), 181.

6 Walter Everett, ‘Singing About the Fundamental Line’, paper read at the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory, Phoenix, AZ, 1997.

7 Claude Debussy, Pelléas and Mélisande, video recording, Welsh National Opera, dir. Pierre Boulez (Deutsche Grammophon, 1994), #6303065910.

8 Vera Maletic, Body - Space - Expression: The Development of Rudolf Laban’s Movement and Dance Concepts (Mouton de Gruyter: New York, 1987).

9 Albrecht Knust, Dictionary of Kinetography Laban (Labanotation), 2 vols. (MacDonald and Evans: Plymouth, 1979).

10 Ann Hutchinson Guest and Claudia Jeschke, Nijinsky’s Faune Restored, No. 3, Language of Dance Series, ed. Ann Hutchinson Guest (Philadelphia: Gordon and Breach, 1991).

11 Richard S. Parks, The Music of Claude Debussy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), Chapter 7.

12 Felix Salzer, Structural Hearing: Tonal Coherence in Music (New York: Dover Publications, 1962), 100; Charles Burkhart, ‘Schenker’s “Motivic Parallelisms”’, Journal of Music Theory 22/2 (Fall 1978): 145-75; Matthew Brown, ‘Tonality and Form in Debussy’s Prélude à “L’après-midi d’un faune”’, Music Theory Spectrum 15/2 (Fall 1993): 127-143.

14 Lawrence Kramer, “Wittgenstein’s Chopin: Interdisciplinary and “the Music Itself,” 2003 conference paper presented at Interdiscipline: New Languages for Criticism, Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities (CRASSH), Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge University, Cambridge, England.