Dementia

and Voice Leading in The Sentry, from Peter Maxwell

Davies's Eight Songs for a Mad King

Martin Kutnowski

Subordination

of Music to Theatre

Explaining

the intimate connection between drama and music is the norm in most analyses of

Peter Maxwell Davies's Eight

Songs for a Mad King. It seems that the potent semantic integration

between music and drama discourages any other analytical possibility. Not that

a word-painting, dramatically-oriented hearing of this masterpiece is

unwarranted; by any means, the connection between theatre and music is made

explicit in the program notes, where the composer states that almost every

musical parameter has a functional part in the depiction of George's

progressive ordeal from madness to death. (1) Michael

Chanan, Paul Griffiths, and others describe the referential substratum of the

music, down to the calligraphic layout of the score: The asynchronous designs

of the instrumental lines depict a state of schizophrenia; the instrumentation

is only a metaphorical representation of the King's mental and physical

reality; the extreme and virtuosic solos are a metaphor for extreme emotional

states. Griffiths makes explicit the connection between musical and theatrical:

an unusually broad vocal range featuring extended techniques matches the

stereotypical utterances of a mentally ill person, while musical quotations of

a long lost illustrious past are to be heard as a disdainful mockery of the

King. (2) In a more recent article, Ruud Welten stresses the

tight integration between musical style and metaphorical representation, and

parallels the King's madness with that of the music. Characterizing the piece

as post-modern, he says that "...disintegration is expressed by random

differentiation in archetypal musical patterns...." (3) Janet

Halfyard traces the stylistic roots of this aggressive theatrical style,

particularly the demented vocal utterances, to Edvard Munch's Expressionistic

scream, Arnold Schoenberg's Pierrot

Lunaire, and Antonin Artaud's "Theater of Cruelty." (4)

The

musical quotations are an obvious theatrical component and help to date the

action and situate it in historical perspective; much like source music (a song

heard on the radio in the background, for instance) is used on a film to define

where and when the action takes place. On one level, the distortions that

affect these stylistically archaic elements - the midway abandonment of a

phrase, the sudden detuning of the keyboard, and the unprepared changes of

tempo or meter, among many others - clearly depict the madness of the King. On

a deeper level, the stylistic distortions situate and anchor the piece to some

of the prevalent musical idioms of the twentieth century, while establishing a

dialectic relationship - by means of an irreverent misrepresentation, or

perhaps purposefully perplexing misreading - with the music of the past.

"Distortion" is the word that Davies uses when referring to the

compositional process: "...The other odd thing about Eight Songs was the idea

of taking lots of different materials and putting them together. I've never

gone in for a very simple montage of unrelated objects, which, for instance,

Berio has done. To me it's always been much more appealing to take something

where you can actually sense the distortion process happening...." (5)

It

is understandable that analyses of Eight

Songs focus on the dramatic/programmatic features, establishing

suitable "meanings" for specific musical parameters or gestures,

because this way of hearing the piece is much in line with the composer's

program notes and performance instructions. Besides, allusion and parody are a

fundamental dialectic component of Davies's style, both in dramatic and

non-dramatic music. (6) But, as pointed out by Jonathan

Harvey and Peter Owens - authors who certainly acknowledge the referential

nature of the music - this intense focus on the programmatic should not neglect

a fair examination of the music as a post-tonal language on its own, and

particularly of its voice leading and harmony. (7)

In

fact, Davies's rejection to juxtaposing contrasting materials by "simple

montage" puts in doubt Welten's idea of "random

differentiation," cited above, and suggests that the quotations from the

standard musical literature present in Eight

Songs - plus the interstitial spaces - are a series of organically

related musical segments, if at least by a unifying, collective path towards

formal distortion. Taking this intuition further, one could look for coherence

that is expressed strictly in musical terms. Finding it would require

suspending the inescapable integration between music and drama, because such

integration obscures the purely musical logic.

Intuitive

Aspects of the Musical Grammar

Jonathan

Harvey describes those elements in Eight

Songs that make sense in purely musical terms. (8)

Notwithstanding the expressionistic nature of the work, Harvey feels that the

utilization of excerpts from the Messiah

is logical. In a symbolic level, he finds formal coherence in that each of the

eight songs is labeled with an archaic dance title, as numbers within a Baroque

suite. In his opinion, the quotations add "...a substratum [of musical

meaning] that is very readily comprehensible...." (9) Harvey

spells out the process of distortion: dances accelerate, get denser, or louder;

familiar tunes are transposed and parodied via polytonality. He finds a

balanced dosage among the pastiche segments, which provide "…the bulk of

the rhythmic motion…," and "…the mainstream argument, which moves in recitative

or independent rhythms…." (10) One of the most interesting

aspects of Harvey's article is his commentary about motivic transformation and

voice leading. He argues that the motive "The Kingdom of this world,"

from the Messiah,

is dissolved (not entirely, one would suppose) into what he calls the

"mainstream music" (the non-pastiche chunks) and that the major/minor

triad that underlies the striking first vocal phrase in The Sentry, "Good

Day," returns in different guises throughout the piece. Most

significantly, Harvey identifies an extended set, comprising sixteen pitches,

as the most fundamental source of pitch material for the whole piece, pointing

out that "...These are sets which are similar or related. The main

characteristic intervals are semitones and minor thirds, and they interlock or

spread out into scales. Two minor thirds separated by a semitone compose the

major/minor triad, obviously. But the striking thing is the frequency with

which the same formations occur untransposed...." (11) Harvey

also identifies the use of permutational methods in "...small sets in ever

varied note order...." He concludes his analysis by listing a number of

devices that give the piece a sense of formal coherence, including, among

others, small- and large-scale, rhythmically-proportioned blocks, and the

recapitulation of lines, textures, and intervallic sets.

Focusing

the Inquiry on Atonal Voice Leading

Is

this music really "mad"? Is it truly non-sensical? Are its musical

ingredients "randomly differentiated," as Welden puts it? (12)

I propose that they are not. Without going as far as to ignore the theatrical

substratum of this work, and following Harvey's and Owens's lead, I therefore

propose that the apparently absolute subordination of the music to the play be

challenged, in part, by searching for elements of the musical syntax that do

not necessarily depend - at least, not in a strict, linear fashion - on the

theatrical artifacts. Inspired by Jonathan Harvey's insights, and following on

the steps of David Roberts and Peter Owens, the ensuing analyses focus on the

first song's voice leading. (13) A hidden layer of musical

logic in the voice-leading dimension would complicate the semantic spectrum

and, dialectically, further counterweigh the structural importance of drama, on

the one hand, and music, on the other. My working hypothesis is that the music

is "mad" in its pathos, but not in all of its structure, and

particularly that there is a hidden logic to its voice leading, independent

from any dramatic consideration. To put it in different terms, the music is a

post-modern collage of modernist ingredients. According to this analytical

strategy, the musical fragments analyzed here are not the stylistic quotations

- or "source music" - but, insisting on the film metaphor, the

original "soundtrack" music of this piece. (These are the

non-referential fragments that Harvey calls "mainstream drama"). The

analyses are focused on specific portions of The

Sentry, which is a song purely written in a twentieth-century idiom

and does not contain any obvious quotations of earlier music. My reading

examines the music in its own right, suspending any referential connection

between the music and the action, and concentrating in the intervallic and

chordal structure of each of the chosen excerpts. I return to the programmatic

dimension in my conclusions, where I integrate my findings in the voice leading

realm with the larger context of the nonsensical drama.

The Sentry (mm. 2-3 after rehearsal mark "A")

Harmonic

Units

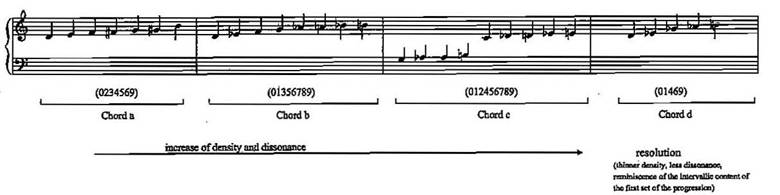

The

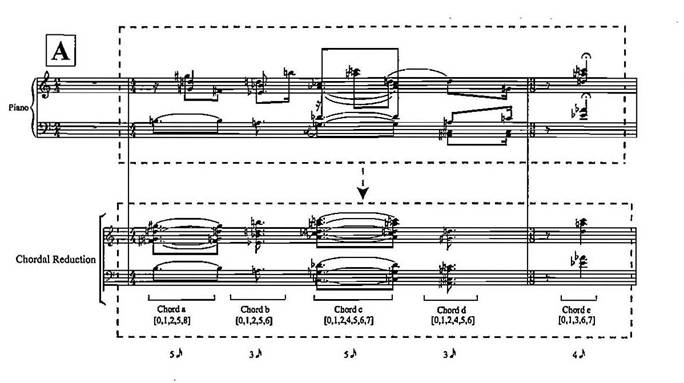

first excerpt is transcribed in Example 1. Only the material featured by the

piano is considered relevant for this analysis. The reduction assumes a

harmonic rhythm essentially in agreement with the metrical foot. In that

manner, and despite the rhythmic distortion introduced in the sixteenth-note

level, each of the four beats of this bar roughly corresponds to a different,

unique set. As shown at the bottom of the chordal reduction, the first set

comprises one quarter plus a sixteenth, the second only a dotted eighth, the

third one again one quarter plus a sixteenth, and the fourth once again just a

dotted eighth. This insight matches Harvey's intuition of "proportionate

rhythmic blocks," and reminds one of Owens's observations about more- or

less-isorhythmic proportions, that is, tonal rhythm, within serial and/or

transformational environments. (14) The final set lasts a quarter

note - which seems to be the elusive durational-rhythmic prototype for each of

the five harmonic units - but is arrived at after a written-out ritenuto by

means of an eighth rest - hence the 3/8 time signature. The obvious immediate

question is to figure out how these five harmonic entities are articulated to

each other, if they are at all and not simply juxtaposed. To answer this

question, all such harmonic instances have to be first examined on their own.

The

first four sets comprise the following (unordered) types: [0,1,2,5,8],

[0,1,2,5,6], [0,1,2,4,5,6,7], and [0,1,2,4,5,6]. The quarter-note chord of the

next bar (3/8) comprises a fifth and last set: [0,1,3,6,7]. In principle, all

these sets in prime form - which I call chords a, b, c, d, and e - seem to be

sufficiently different from each other to discourage any kind of consistent

voice-leading connection; their intuitive commonality comes from sharing

specific subsets such as [0,1,2,5] and [01,2]. But taken as a whole, only

chords a, b and e have the same number of pitches, five. Chord c contains seven

pitches; chord d contains six. In fact, it would seem that the only

surface-related features of this progression that make sense in terms of

traditional phrase structure have to do with register and rhythm: Chord e

features a noticeable displacement towards the treble region; this sonority is

also articulated after an eighth rest - the written-out ritenuto - and after

the other instruments stopped playing. These surface elements alone would suggest

a sense of arrival similar to the effect of a cadence, if only by means of

contrast.

One

more intriguing aspect of the manuscript remains unexplained at this point, and

has to do with the peculiar disposition of the stems in the piano part. In

chord a, for instance, and whereas the left hand seems to have a lone B3

assigned, the right hand contains four notes, and the stems group the interval

of a perfect fifth (G4-D5) in the middle, separated from the interval of a

major ninth in the extremes (F#4-G#5). To be sure, the stemming is necessary to

make clear the rhythmic distinction between the two intervals (the perfect

fifth is a harmonic interval that lasts an entire quarter note and the major

ninth is a melodic interval in eighth notes). But the voicing of the chord, a

contrapuntal gesture borrowed perhaps from vocal music but very unusual and

attractive from the pianistic point of view, may be offering a key hint about

the elusive harmonic organization of the excerpt.

Near

Transposition

On

the one hand, there are so many intervallic discrepancies among the sets that

one would be initially discouraged to search for a common transformational

formula; the sets would simply be juxtaposed one after another. On the other

hand, it seems intuitively apparent that each set smoothly evolves into the

next, hinting at a hidden coherence in the progression. How can one conciliate

these two intuitions? Because the sets are not transpositionally and/or

inversionally equivalent, strict transpositional or inversional procedures must

be ruled out. But a less strict notion for equivalency allows one to see that

the progression is not built on mere juxtaposition. The quasi-transformational

journey is shown in Chart A.

|

Chord a |

[0,1,2,5,8] |

|

Chord b |

[0,1,2,5,6] |

|

Chord c |

[0,1,2,4,5,6,7] |

|

Chord d |

[0,1,2,4,5,6,x] |

|

Chord e |

[0,1,3,6,7] |

("x"

denotes the absence of a pitch class)

Chart A: PC Sets of Chords of The Sentry at Rehearsal A

The

first four harmonic units listed above seem to map into each other in what

Joseph Straus calls "near inversion" or "near

transposition" relationships. In the progressions between chords a-b and

c-d, all the notes but one move to Tx; in the progression between chords b-c

all the notes but two move to Tx. (15) As shown in the chart, from

chord a to chord b all intervals are retained except [8], which becomes [6];

from b to c all intervals are retained, but two more, [4] and [7], are added;

from c to d all intervals are once again retained but one [7] is left out. But,

from d to e, only one interval remains, [0,1], while three [2,4,5] are left out

and two more, [3,7], are added. The configuration seems in fact to suggest a

gradation of change or, more specifically, a certain order within a relatively

structured - controlled - process of transformation. This process is

reminiscent of the gradual voice-leading shifts that Stephen Pruslin finds in

the "Second Taverner Fantasia." (16) The

greater difference between the last two chords, as shown in Chart A, would

confirm the cadential nature of the closing segment, much in agreement with my

previous observations on surface rhythm and register; the stronger

discrepancies surrounding chord c - a set which contains two differences from

the previous chord - only suggest a sense of climax because the transition to

this chord is less smooth - more dissonant - than the rest of the progression.

Because this chord contains more pitches than any other chord in the

progression, the climactic nature is thus also suggested by the heavier density

of the texture. Lastly, chord c also features the highest note of the phrase,

C6, in the right hand - this note is repeated in chord d, but featured in a

softer dynamic, pp. As if to further confirm the intuitive relatedness

of all five sets involved in this phrase, the first and last would become

identical by leaving out one offending pitch in both sets (F# in set a, D in

set e; both sets would be [0,1,4,7]). But the absent connection between chords

a and e, as shown by this strict comparison among the complete sets in their

prime form, would suggest no sense of return to harmonic stability at the end

of the phrase. At the very least, keeping the sets complete and in their prime

form may make more difficult to see such return.

"Permutational

Methods in Small Sets"

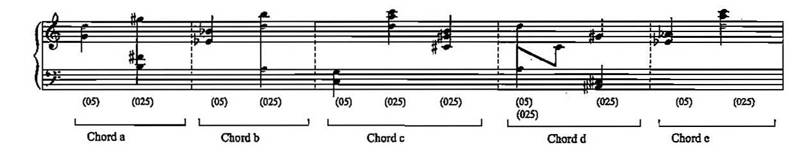

Yet,

a more daring idea allows the emergence of a more persuasive analytical

picture. Instead of looking at each of these chords as wrapped entities, one

can see them as the expression of simultaneities arising from the combination

of smaller units of meaning, much in the same way in which individual intervals

- and not necessarily triads - were the primordial building blocks in

Renaissance counterpoint. (17) According to this idea, the

seed of which is in what Harvey calls "permutational methods in small

sets," (18) each of the five sets described in Chart A can be

seen as a composite, and broken into smaller units comprising fewer pitches, as

long as such individual units map meaningfully into one another. In one case,

one can look for patterns in which one portion of these sets remains constant -

an axis of rotation - while another portion of the set - a smaller segment,

perhaps just one note - becomes variable. Another possibility is to look for

patterns in which smaller, constant subsets are interlocked in a kind of

contrapuntal design. Both cases are expressed in Example 2, which re-organizes

the chordal reduction of Example 1. The peculiar way in which the notes are

stemmed in the manuscript seems to indicate that in the first set, chord a, G#5

and F#4 belong together, while G4 and D5 comprise another subgroup. In the next

beat, chord b, a similar design is encountered: E flat 4 and B flat 4 are notated

separate from D5 and B5. Similar features can be found in chords c, d, and e.

The intriguing design of the stems suggests that each set is the manifestation

of two and sometimes three actual sets; in this way, a fully transpositional

pattern finally emerges, one only involving set classes [0,5] and [0,2,5].

Example 1: “The Sentry” – Eight Songs for a Mad King Rehearsal

Mark “A”

Example 2: “The Sentry” – Eight Songs for a Mad King Reorganized Chord

Reduction

Example

3 offers an in-depth model for the transformational exchange. The example

disregards original registers; the chart is a representation on staves of

pitch-class mappings. In the upper system, each one of the entire sets is

presented with distinct stems, each defining two subsets: [0,5] and [0,2,5].

All the pitch classes of the segment can be accounted for in this way. The two

systems, vertically aligned, show the two subsets generating their own

simultaneous and independent transpositional and/or inversional paths, which

are expressed with transformational arrows and labeled according to the

interval of transposition or inversion. The horizontal and oblique lines among

sets express the mappings from one set to the next; parallel lines express

transpositional relations, while oblique lines represent transpositional +

inversional relations (as in the top layer, where the TI relationship is shown

in the mappings from DBA to DCA and from DCA to C#A#G#). The separation between

treble and bass staves (subset [0,2,5] in the treble, subset [0,5] in the bass)

is justified to the extent that the subset [0,5] is prominently featured in the

musical surface: The five occurrences of subset [0,5] correspond to the five

beats comprising the progression and, in this sense, the regularity of the

tonal rhythm in the lower layer could be understood as a kind of "cantus

firmus," logically aligned with the basic pace of the fragment. (19)

The treble layer, expressing the subset [0,2,5], in contrast, speeds up in

chords c and d, which feature each two instances of the subset [0,2,5] for each

of the occurrences of the subset [0,5]. In Example 3 this feature is captioned

as "two sets against one," a play on words alluding to the rhythmic

configuration typical of second species counterpoint. Alternatively, chords c

and d can be understood as featuring a "subset divisi" that thickens

the texture, before the last chord restores the five-pitch contrapuntal density

- and, together with it, the relative stasis - of the beginning of the phrase.

Example 3: “The Sentry” – Eight Songs for a Mad King Rehearsal

Mark “A”, Model of Transformation Exchange

My

analysis proceeds in a deconstructive way, decoding otherwise unintelligible

harmonic occurrences by breaking them into smaller units of meaning. Building large

sets by combining smaller ones is an integrative way to generate pitch

material. Curiously, this approach is perhaps the complement of the reductive

process which David Roberts and Peter Owens call "sieving," a

compositional tool often used by Davies to generate new melodies by filtering a

few pitches from a preexisting chant. (20)

The Sentry (mm.

2-3 after rehearsal mark "D")

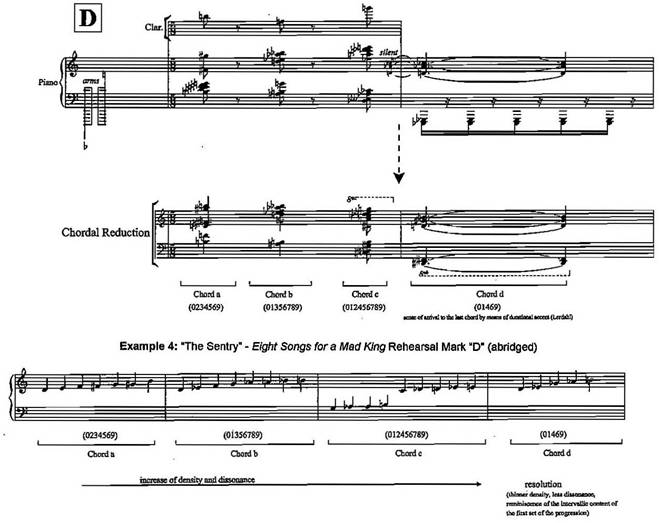

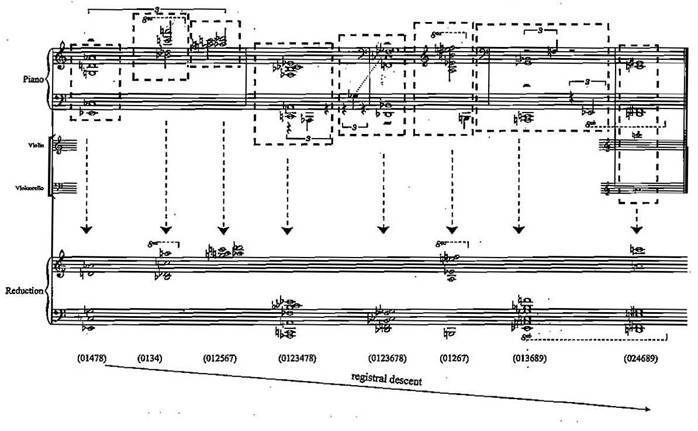

The

next fragment analyzed here corresponds to rehearsal letter "D." This

excerpt is similar to the one corresponding to letter A in the sense that it

features a clear-cut, post-tonal, chord progression. In this case the clarinet

line and the piano are fully integrated, both in register, dynamics, and

rhythm. For this reason, all the simultaneously sounding pitches of these two

instruments are understood as components of the same sounding object, and hence

taken into account in the construction of the sets. Example 4 is an abridged

version of the excerpt - percussion and voice are reduced out.

Example 4: “The Sentry” – Eight Songs for a Mad King Rehearsal

Mark “D” Abridged

Example

5 abstracts the musical surface to the four sets featured in the progression.

Even at this preliminary stage of the analysis it's possible to perceive a

sense of arrival at the end of the phrase, which is created, in part, by what

Fred Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff call a "durational accent" in A Generative Theory of Tonal Music:

the last chord lasts longer than any of the previous chords of the phrase, and

is thus perceived as a point of relative stability and goal of the fragment.

Although Lerdahl and Jackendoff's treatise is focused on tonal music, their

definition of durational accent can be applied to any kind of musical grammar.

Furthermore, the authors identify duration as a universal marker of stress,

common both to music and prosodic language. (21) In

addition to a new timbre, the last chord also features different dynamics and

surface rhythm, and a strikingly different register (the lowest region of the

piano, bluntly contrasting with the high register of the clarinet in the rest

of the phrase). The repetitions of the left hand also set apart the last chord,

for repeated notes have in essence more life than sustained ones in a

percussion instrument like the piano. The repetitions provide, in the rhythmic

realm, a summary of what happened in the phrase as a whole; the iteration of

sixteenths (a kind of written-out, eighth-note staccato) is a fainter, weaker

"echo" of the percussive motive, creating a motivic reminiscence of

the three strikes present in the first measure.

Example 5: “The Sentry” – Eight Songs for a Mad King Rehearsal

Mark “E” Abstraction of Four Sets of Example 4

Motivic and Intervallic Consistency

The

life of the phrase is also artfully sculpted in terms of relative dissonance,

which increases as the phrase progresses. The last chord features a kind of

resolution via its thinner timbral density (the texture includes piano

harmonics in the right hand, and the clarinet is now silent), and via the

harmonic content: The left hand only holds a surviving minor third, E flat1-G

flat 1, which is reminiscent of the interval between the two top voices in the

first set of the progression, G#5-B5. Whereas the disparity in density and

harmonic complexity between chords c and d would seem to discourage any kind of

connection, some connections start to emerge as soon as the larger set is deconstructed

into smaller segments. One then finds that [0,3] is profusely present as

interlocking dyads: A flat-B, C-E flat, E-G, A-C and D flat-E in the immediate

pianistic surface. Along these lines, and reinforcing the perception of a

controlled voice leading, a deeper look at the last set reveals that it is a

quasi-summary of the first, for the two of them share the subset [0, 2, 5, 8]. (22)

Near-Mappings among Small Sets

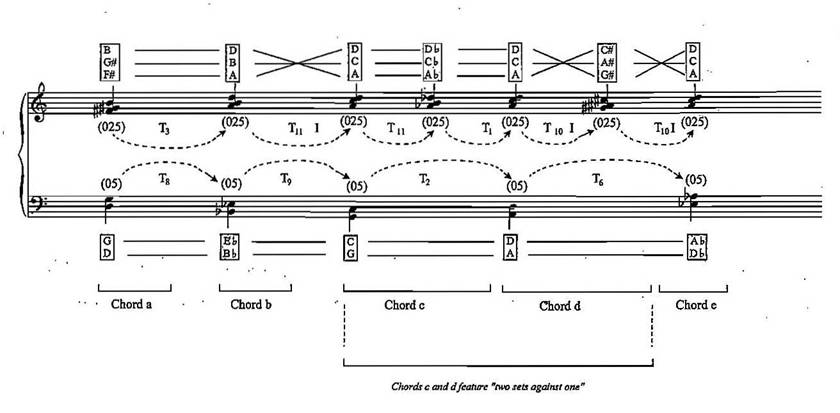

As

it was demonstrated in the analysis of the previous excerpt, understanding each

set as combinations of smaller subsets sheds light on otherwise obscure

transformational connections. The notion of quasi-transposition, plus the

separation of larger sets into contrapuntal subsets finally unveils the voice-leading

logic, as shown in Example 6. On the top system, the larger generating sets are

expressed, simply enumerating all the pitches that are present in the musical

surface, and with the same registral disposition. In the system at the bottom,

the two strands of subsets are shown - once again arbitrarily separated into

the bass and treble staves.

Example 6: “The Sentry” – Eight Songs for a Mad King Voice-Leading

Logic

The

specific pair of notes that features the quasi-transposition is shown in each

case with oblique dotted lines. Near-transposition relationships are indicated

with an asterisk preceding the transpositional label: *Tx. The graph allows one

to see that the top voice follows a coherent path towards distortion that

intensifies at the end: [0,1,2,3], [0,1,2,3], [0,1,2,3,6], [0,1,4,6,9]. The

example features two asterisks besides the transpositional symbol (**T1 in the

treble staff) to express such lesser degree of transpositional consistency - or

more dissonance - between the last two members of the progression. In contrast,

the lower voice follows a steady quasi-transpositional journey, changing only

one interval from one set to the next. The transformation between the two first

sets is fully transpositional; the one between the second and third chords is

quasi-transpositional; the progressions between the two last sets involves not

one but two intervallic changes. This progressive path towards increased

dissonance confirms the uniqueness of the last set and the general meaning of

the harmonic content: The patterns of voice leading are more consistent (or

more consonant) at the beginning and less consistent (or more dissonant)

towards the end of the progression. Ultimately, this observation coincides with

the breaks of the rhythm and texture and the drop in register at the end of the

phrase, as discussed above. As with the excerpt corresponding to rehearsal

letter A, examined in Examples 1-3 the harmonic detachment of the last chord of

the progression, featuring the weakest connection of the entire progression,

can be interpreted as a cadential gesture.

The Sentry (rehearsal mark "E")

Harmonic

Units

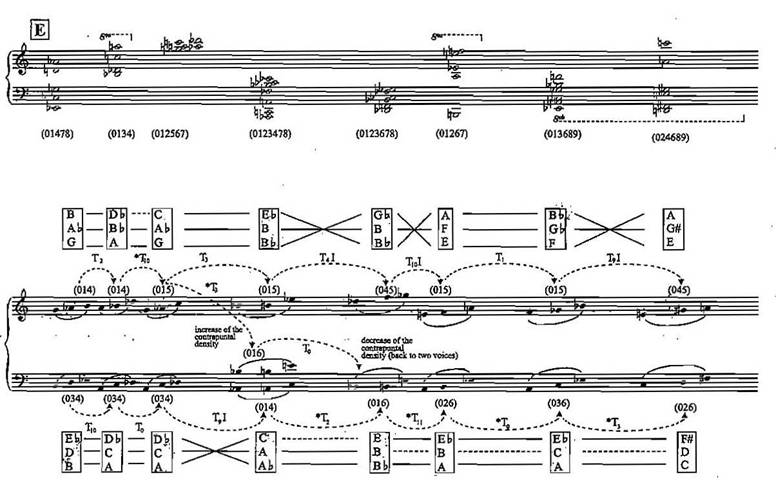

The

last fragment analyzed here corresponds to rehearsal letter E. The excerpt can

be understood as featuring three sonic layers, all with a distinct function.

The voice features the purely dramatic dimension, the percussion featured by

the tambourine is the equivalent of a special-effects layer, and the harmonic

entities featured by the piano plus the strings are the actual

"music" of the excerpt. The reduction also assumes a kind of

pseudo-regularity in the harmonic rhythm. In essence, each struck chord in the

piano is understood as a homogeneous entity, defined through timbral and

rhythmic means. Some notes with certain rhythmic independence must be

rhythmically normalized, and hence assigned to the previous or next chord (for

instance, G flat 3 on the bass staff at the end of the second bar of the

excerpt). In each case, the normalization is based on different factors, from

simple proximity to common-practice considerations; G flat 3 at the end of the

second measure could be heard as a direct anticipation of the next G flat 3 in

the downbeat of the third bar.

Example 7: “The Sentry” – Eight Songs for a Mad King Rehearsal

Mark “E”

As

in the two previous harmonic progressions analyzed above, register plays an

important part in securing the coherence of the phrase. Beyond the constant

widening and narrowing of the registral space, a generalized

pseudo-Expressionist tendency towards the low register in the piano

materializes at the end of the phrase with an arrival to D1 in the left hand.

This attraction towards the lower register balances, in contrary motion, the

generalized upwards tendency of the voice, which reaches E flat 2 in the second

measure and ends, four octaves higher, on G5.

The

reduction defines eight set classes: [0,1,4,7,8], [0,1,3,4], [0,1,2,5,6],

[0,1,2,3,4,7,8], [0,1,2,3,6,7,8], [0,1,2,6,7], [0,1,3,6,8,9], and

[0,2,4,6,8,9]. The sets are all different, precluding any strict

transformational voice leading. Once again, the challenge consists in

discovering an alternate pattern of articulation among these sets, before

giving up to the idea that they are all merely - or "madly" -

juxtaposed.

Near-Mappings

among Small Sets

The

analysis continues in Example 8. The upper system contains the larger sets as

presented in Example 7. As with the previous examples in this study, in the

lower system the larger sets are broken down into smaller subsets; these

subsets are subsequently assigned to one of two pseudo-contrapuntal strands. As

before, the placement of the upper and lower voices is arbitrary and only

motivated by the goal to facilitate the visualization of the two

transformational paths. The subsets of the top voice are thus [0,1,4], [0,1,4],

[0,1,5], [0,1,5], [0,4,5], [0,1,5], [0,1,5], and [0,4,5]; the subsets of the

lower voice are [0,3,4], [0,3,4], [0,3,4], [0,1,4], [0,1,6], [0,2,6], [0,3,6],

and [0,2,6].

Example 8: “The Sentry” – Eight Songs for a Mad King Rehearsal

Mark “E” Continued Analysis

All

the transformational arrows are transpositional or quasi-transpositional -

suggesting a consistent voice-leading - but a few analytical licenses that are

used to make sense out of the mechanism of the progression must be explained.

In the first place, the first chord contains only five pitches (G, A, B, D, E

flat), but the two subsets contain three pitch classes each, in appearance

totaling six. That is because one of them, B, has been doubled, and it is

therefore present in both subsets. The intriguing notion of a "hidden

doubling" in a post-tonal language is beyond the scope of this paper, but

I am applying this concept by analogy to the way in which doublings are

understood in tonal music; both tonal and post-tonal music accept octave

equivalency as a common principle. In addition, the presence of B in both

subsets can be seen as necessary: William Rothstein describes situations in

which tones that are absent can be inferred by the surrounding context, most

especially when such implied tones are required to complete linear,

contrapuntal, or harmonic archetypes. (23) Along

these lines, the presence of pitch class B in both subsets would be required by

the transformational logic of the two contrapuntal strands. A similar situation

presents in the second pair of subsets, which both include pitch class A.

Another

intriguing moment occurs when the contrapuntal density increases to a texture

containing three voices. This happens in the transition from the third to the

fourth sets. At this time a middle-voice emerges, perhaps as a divisi of the

third upper-voice subset, at *T3. The texture rapidly returns to a two-subset

counterpoint in the following chord: While the upper voice continues at T4I,

the middle voice merges with the lower strand at T0. The resulting repetition

of [0,1,6] from the fourth set - in the middle-voice - to the fifth -

transferred to the lower voice - generates yet another curious situation: A

kind of oblique motion between the lower and upper strands. This reminiscence

of second species counterpoint, which I called "two subsets against

one" above, is also present in the progression between the second and

third sets, where the literal repetition of the subset at the lower voice

([0,3,4], with an arrow labeled as T0) seems to imply a kind of oblique motion

between the upper and lower subsets, and it is also present in a subtler way in

the progression from sets six to seven, where *T0 connects the two lower subsets

[0,2,6], [0,3,6], while the upper voice moves T1.

Conclusions

The

Sentry is a chapter within a piece of

musical theater. As such, most of its musical features are primarily justified

by its dramatic requirements. In a deeper level, however, the music resists a

formal examination on its own and exhibits intriguing features of highly

structured - and highly complex - post-tonal voice leading. As it is frequent

amongst works written in post-tonal languages, in this song the voice leading

is often concealed and deconstructed through brutal breaks in the register,

texture, or dynamics. The sophisticated concept of quasi-transposition,

however, unveils aspects of the piece that suggest a highly structured approach

to composition in the pitch realm, if only in isolated, disconnected segments.

The piece is thus organized as a distinct collage of non-organic parts, but

some of these parts - parts which are neither perceived as allusion nor parody

- exhibit a logical, intrinsically structured musical organization.

Quasi

transposition and set partitioning unveil patterns of regularity, making

evident a sense of internal pitch organization far from casual or aleatoric.

Owens speaks of a continuum from deliberately obscure to deliberately explicit

motivic or serial processes in the music of Davies. (24) My quasi-transformational analyses are probably closer to

the dark pole of the axis; in any case, the voice-leading devices described

here are buried and interspersed within a multiplicity of other musical

parameters, and therefore account for and explain only a small portion of the

technical complexities of the whole piece.

In

the semantic realm, however, it is possible that these hopelessly disconnected

islands of structured meaning gently offset - if only briefly - the generalized

perception of mental disorder that constitutes the pathos of the piece.

Arguably, quasi transposition allows one to see that there is an important

commonality between the alternating segments that Harvey calls "mainstream"

and "parodic": Each of the examples featured in my analyses is

similar to the parodic allusions in that it remains coherent - recognizable,

stylistically sound - to itself, but without generating or articulating into a

larger form. Unveiling the techniques of post-tonal voice leading at play in The Sentry is perhaps like

taking a brief revealing glance at the King's madness, perhaps even realizing

that his ranting does, only to some extent and sporadically, make sense. By

finding order within disorder, reason within absurdity, small-scale voice

leading within large-scale juxtaposition, quasi transposition allows the

perception of yet one more perplexing layer of subtext within the schizophrenic

riddle proposed by this music.

1. Peter Maxwell Davies and Randolph Stow, Eight Songs for a Mad King

(London: Boosey and Hawkes Music Publishers, 1969).

2.

Paul

Griffiths, Peter Maxwell

Davies (Robson Books, London, 1981), 14, 65, 69; Michael Chanan,

"Dialectics in Peter Maxwell Davies," Tempo 90 (Autumn, 1969), 12-22.

3.

Ruud

Welten, "'I'm not ill, I'm nervous' - madness in the music of Sir Peter

Maxwell Davies," Tempo

196 (April 1996): 21, 23.

4.

Janet

Halfyard, "Eight Songs for a Mad King: Madness and the Theatre of

Cruelty," paper given at A

Celebration of the Music of Peter Maxwell Davies, March 31-April 2,

2000, St. Martin's College of Performing Arts, Lancaster. Accessed on August 8,

2004 from: http://www.maxopus.com/essays/sick.htm. ril 2, 2000, St. Martin's

College of Performing Arts, Lancaster. Accessed on August 8, 2004 from:

http://www.maxopus.com/ essays/8songs_m.htm; the connection between vocal

technique and madness is also explored in Alan Shockley, "Insanity,

Abjection and Extended Vocal Techniques in Eight

Songs for a Mad King and Miss

Donnithorne's Maggot OR the Texts and Techniques of Madness.

5.Paul Griffiths, Peter Maxwell Davies, 111.

6.

Chanan,

"Dialectics"; Arnold Whittall, "Comparatively Complex:

Birtwistle, Maxwell Davies and Modernist Analysis," Music Analysis 13:2-3,

1994: 139-159.

7.

Jonathan

Harvey, "Maxwell Davies's 'Songs for a Mad King,'" Tempo 89 (1969): 2;

reprinted in Peter Maxwell

Davies: Studies from two decades, ed. Stephen Pruslin (London :

Boosey & Hawkes, 1979); Peter Owens, "Revelation and Fallacy:

Observations on Compositional Technique in the Music of Peter Maxwell

Davies," Music Analysis

13:2-3 (1994): 161, 163.

8.

Harvey, "Songs," 2.

9.

Ibid.,

3.

10.

Ibid.,

4.

11.

Ibid., 5.

12.

Welten,

23.

13.

Harvey,

"Songs"; Owens, "Revelation," David Roberts,

"Techniques of Composition in the Music of Peter Maxwell Davies"

(Diss., Birmingham University, 1985).

14.

Harvey, "Songs," 5;

Owens, "Revelations," 171-2, 175-6.

15.

Joseph

Straus, "Voice-Leading in Atonal Music," in Music Theory in Concept and Practice,

ed. James Baker, David W. Beach, and Jonathan Bernard (Rochester: University of

Rochester Press, 1997). The same concept is discussed by David Lewin in

"Some Ideas About Voice-Leading Between Pcsets," Journal of Music Theory 42

(Spring 1998).

16. Stephen Pruslin,

"Second Fantasia on John Taverner's In Nomine," Tempo 73 (1965): 2-11.

17.

Incidentally,

Medieval plainsong has been noted as one of the most important sources of

thematic material in Peter Maxwell Davies's music. See Bayan Northcott,

"Peter Maxwell Davies," Music

and Musicians 17/8 (April 1969): 36; Owens,

"Revelations," 164; Chanan, "Dialectics," 12; Whittall,

"Comparatively Complex," 157.

18.

Harvey,

"Songs," 5.

19.

Basic

pace is defined by Channan Willner in "Sequential expansion and Handelian

phrase rhythm," Schenker

Studies 2, ed. Carl Schachter and Hedi Siegel (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1999), 192-221.

20.

Owens,

"Revelations," 165.

21.Fred Lerdahl and Ray

Jackendoff, A Generative

Theory of Tonal Music (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1980), 80-85.

22.

What

I call "motivic and intervallic consistency" can be equaled to what

Owens calls "thematic processes" in his discussion of the Hymn to Saint Magnus,

Taverner's Fantasia, and Worldes

Blis. See Owens, "Revelations," 168-9.

23.

Rothstein, William: "On

implied tones," Music

analysis 10/3 (October 1991): 289-328.

24.

Owens,

"Revelations," 176-7.