Architecture

and Aesthetics: the Construction and the

Objectives of Elektronikus

Mozaik

David Keane

Elektronikus Mozaik

is a

tape composition made with a Yamaha

DX-7 synthesizer. This paper is a

considered and vigorous attempt to

articulate clearly and precisely

the philosophical and psychological

architecture of the work. My

objective in the composition itself was, by

reducing the

role of other parameters, to allow timbre to occupy the

primary

focus of the listener's rational and intuitive mental processes.

The

work is very much concerned with the role of expectation operating

at

very limited local levels. It is further concerned with the concatenation

and integration of these

levels to produce a vast, many-tiered system of possibilities for the listener to engage in mental interaction with the processes of the piece. This approach requires many

assumptions about the nature of the

generalized listener as well as the individual listener. The approach also requires some serious thought

about the relationship of the

composer's own response in relation to that of listeners, and to that of any particular listener. The paper outlines

specific aspects of repetition, pattern, and progression and illustrates

these principles. The potentials of the DX-7

for precise timbral control and flexible, reliable, real-time, manual

operation were major determinates in the construction of

Elektronikus Mozaik.1

Introduction

Elektronikus Mozaik

[electronic mosaic] for

stereophonic tape was commissioned by Ivan

Patachich, Music Director of the Hungarian National Film Board [MAFILM] in cooperation with the Hungarian performing rights agency, ARTISJUS. The work had

its official first performance at the

Ferenc Lizst University of Music in Budapest in May,

1984. Elektronikus Mozaik was realized

using the Yamaha DX-7

synthesizer and the resources of the Queen's University Electroacoustic

Music Facility in

Kingston, Canada.

This paper

began as an attempt to describe how I have applied to

the structure of the composition some basic assumptions about how

music works. I have found in the

writing, however, that the assumptions

demand more explication than the

actual applications. My title proposes

a tour of the architecture of this work for tape and I offer as much as

time and practicality

will allow. I wish it were a walk through the rooms and

corridors to show you what the

place is like during normal working hours.

But at least I can let you look

at the plans. I am not going to give you the

statistics of how many man/hours

it took to build it, or how many bricks

have been stacked upon one another. If those things matter, it will tell

in the daily operations;

if they do not matter, there is little point in raising the

topic, anyway. I want you to see how

it is supposed to work.

I am

belaboring this point because composers' analyses are too

frequently discussions of what the

composer

did when the piece was

constructed, what step was

followed by what step. It is almost as though

the analysis

and

the piece of music

is a monument, a mausoleum to

those actions. In this paper, I

wish to present a discussion of the

workings of

Elektronikus Mozaik

with reference to those mechanisms

which have been set up for the

functioning vital processes of the music,

processes which give this work

its identity in time and space. I am

concerned not with what /did to

make the piece, but, rather, with what the

piece of music

does when it is lived in.

Having made

the point that my emphasis is upon the dynamics of music and listener, I must

temper what I have already said by admitting

that my concern is, after all, with my

intentions

(in the past) for what

the music will do when it

is performed (in various futures). Music is a highly

interactive process. What a

piece of music is doing at any particular

moment in any particular situation is very much a product of not only the

physical qualities of the

sound, but also the contribution of each listener. The workings of a piece of

music, then, are really an assessment of what

the music does, or may do, to

each listener, all listeners, a cross-section

of all listeners; and what the

listener does in response. The following is

merely one modest attempt to

understand a ponderous piece of our

world; but I am determined to try to penetrate the dank fog of musical

arcana, if only a few

inches at a time, rather than stumble blindly ahead,

as I otherwise must do.

It is very much

my bias that the way the general public listens and

responds to music

matters.

I would, however,

qualify general public to

refer to that portion which actually

listens

to some type of music.

Those individuals who

have learned to use music around them as an ambient-noise

mask to quell the sonic variety of the world may be beyond the

potential for

any

music to register

upon their consciousness.

Nevertheless, the quest for

successful means of attracting and engaging

the mental

processes of those individuals who still have the potential, has

the highest priority in my work as a

composer.

Other

Listeners

When I speak,

(as I have done in my last sentence) of listeners and

how I think

their mental processes behave or might behave, I am

occasionally

criticized: "How dare I presume to know anything about how people listen to

music?" That is, people other than

myself.

There seems

to be a common view that it is

acceptable, even desirable, for a composer

to be consumed with his/her

own musical responses, but there is

something a little disreputable

about considerations for any other listener.

I am compelled to respond to that view before I proceed, because

what I have to say in this paper is predicated upon my right to think about

those people who will

listen to my music. If opposition is supported by

the assertion

that the only listener whose thinking a composer

can

know

about is his/her own, I would

ask for some important qualifications: I

would agree that, of course,

it is formidably difficult to understand just

how anyone

else

thinks in

response to music. Nor would I urge that overt

or inferred attitudes of any

other person(s) should be models for a

composer's aesthetic

judgements. On the other hand, I would observe that the composer of a piece of

music is quite different from any other

possible listener to that

particular piece of music in that he/she knows 1)

how the piece was assembled

and 2) what his/her objectives for the

piece were. For me, an

essential aspect of listening to a piece of music is

the act of gathering a sense

of what it is doing, where it is going. That

essence begins only with the

piece itself. When I listen to someone

else's music,

it is what the

piece

tells me

(and my act of listening to what it

tells me) that is important.

What is not important is what the composer

actually did or what the

composer was actually trying to do. If the piece

does not tell me, those

things are of no consequence - except perhaps to

a musicologist for purely

historical reasons. Consequently, what the

composer

knows

a posteriori

not only competes with what the music

might have

to say to him/her, but may completely obscure it with the stuff

of dissertation appendices.2

Thus, what the composer, prejudicially numbed by expectations

and burdened with extensive experience of the fragments in isolation as

well as the whole, thinks he/she comprehends from one hearing of the

piece is

about as far removed from what someone else may hear as is conceivable.

Yet I would urge that the composer try to overcome those very obstacles.3

Moreover, I

would hasten to point out that I am not here concerned with what might be

called taste. That is something that, for the composer,

is exerted at more elementary

levels of the making process: deciding

what

to do. The decisions made at that level are then evaluated from

his/her perspective as a listener: deciding how to make it work. The task

is to apply the experience of hearing the music of others to listening to

one's own work. As difficult as this may sound, it seems to me better than

making

no attempt at all to assess how others may respond.

The

assessment of whether or not the structure works (that is, does

it do something useful toward

some apparent end) is the evaluative

process with which I am

concerned. Taste poses what to do, and, once

tried in some way, the second

kind of evaluation determines whether to

keep it or throw it out. The

two assessments get terribly tangled in reality

because the composer

frequently moves back and forth from the one to

the other in the making

process. However, one can separate the two in

analysis of the process. I

would illustrate this by pointing out that

someone else's music may not

be to our taste, but that does not

necessarily prevent us from

appreciating, or even enjoying, the music if it

appears to work.

I maintain

that the most practical of objectives that a composer

might choose to embrace is to

undertake to construct a framework in

which his/her listeners might

engage in a dialogue with the music. This

may seem to imply that the

composer cater to the listener, but, please, do

not understand me to be

suggesting that the composer pander to the

market; to the taste of

others. What I do propose is that the appeal be

made to the potentials of the

human mind as best as the composer can

comprehend them; to provide

where to look for the first time listener and

more places to look for the

second time listener (although the listener will

increasingly take care of

him/herself in subsequent listenings, if

motivated to do those

listenings). The composer considering listeners in

the making of a composition

does not make unwilling choices, but,

rather, where there are

choices, has one more level of guidance to make

the selection that much less

arbitrary.

What a Working Work of Art Offers

I sincerely

believe that the most effective forms of art are those

which are self-explanatory.

That is, they require as preparation for

understanding the elements

and forces of the artwork no more specific

experience of the world than

that which can be assumed to be possessed

by an average or typical

member of the culture. Within itself, such a work

contains fundamental principles of

how,

and

why

it was made.

Just one

example of this is the architectural instance of a pyramid.

An observer may look at a single block, comprehending its shape and

position in space - first

relative to the observer, then relative to the blocks

around it, and eventually

relative to the structure as a whole -understanding

how the nature of the single block

caused

the pyramid to

be what it is. The

pyramid is a reasonable, if not compellingly

appropriate, consequence of

the single block being placed in a particular

juxtaposition with another,

and these two with a third, and so on. Further

consideration on the part of

one person may encompass the sense of

proportion, symmetry, and

reconciliation of triangle and square. Another

person may have an

involvement in a sense of the massive weight of the

blocks and the enormous

energies called for in moving and erecting the

elements of the pyramid,

while another person may become concerned

with the effects of time and

the elements which have imparted

individuality to blocks that

were made to be essentially uniform. But all these considerations, and many

others, are nevertheless founded upon

the essence of the pyramid.

All these musings spring from an

appreciation of the internal

relationships of the structure. Each person may muse, sooner or later, upon

those considerations pondered by the

others, to some degree, at

some point. But fundamental to all these

senses of the pyramid is the

action of the mind pondering matter,

suggested by the sensations

stimulated by the pyramid.

Of course,

thoughts need not begin with individual blocks. One

may well observe the pyramid

from a distance and obtain a sense of the

structure as a whole, without

particular awareness of its parts. Should

one begin with the whole and

work down to the single block, the sense of

the relationship remains as

compelling: in this case, how the nature of

the pyramid caused the single block

to be what it is.

It is not at

all important where one begins - it is the action of the

mind moving

between

and

among

conceptions of

the whole and

conceptions of the part that gives artistic experience its quality. Dilthey,

after Schleiermacher, suggested that to understand any linguistic unit (a

paragraph), we must

approach it with a comprehension of the constituent

parts (sentences, phrases,

words, morphemes), yet we can understand

the parts only by having a

prior sense of the whole. Dilthey maintained,

however, that this apparent

dilemma (known as the hermeneutic circle) is

not a vicious circle, in that

we can achieve a valid interpretation by a

sustained, mutually

qualifying interplay between our progressive sense

of the whole and our

retrospective understanding of its component parts

[Abrams, p. 84]. This is not true

of language alone.

Fundamental Conception of Elektronikus Mozaik

I need now

to be more explicit about parts and wholes of

Elektronikus Mozaik.

If the work did not begin as

an analogy to a

technique of the graphic arts, it did begin, in fact, as a strategy for the

employment of the

DX-7. I had ordered the synthesizer with the

commission for MAFILM in mind

as its first use, but by the time I had

received the instrument,

less than eight weeks remained for the

completion of the work. Thus,

I looked for an approach that used the best

aspects of some of the elementary

functions of the DX-7.

That

thinking began to frame a fundamental objective for the work.

The timbral range of the

DX-7 is impressively vast and yet may be

precisely controlled with a

minimum of programming. Thus, I determined

to allow similarities and

differences of timbre to occupy the primary focus

of the listener's analytic and

relational mental processes and to form the

principal activity of the

piece within that realm. One analogy frequently

made in reference to musical

timbres is colour. At this point I could see

common bases between, on the

one hand, the small regularly placed

stones of the mosaic and my

short regularly placed durations; and, on the

other hand, the colours of

the stones and the timbres of my points of

sound. I could quite readily

see that what could work for the mosaic

could as easily work for a

musical mosaic. I stress the commonality.

Mosaics are not the

rationale; the common features of perceiver

interaction provide the rationale.

I chose to

manually operate the instrument by means of the

keyboard and, because I had no time to determine whether I could easily

develop instrument

descriptions which were any more interesting or

flexible than the canned ones,

I chose to use the factory supplied ROM

cartridge instruments

[frequently amended to suit my immediate purpose].

In that these were indeed the

elementary functions of the instrument, the

question was: what could I,

with my distinctly unremarkable keyboard

technique, offer that the

average fifteen-year-old visiting the local music

store to play a few licks on

the DX-7 could not? The answer was:

restraint.

By means of

an

intensive use of a

limited feature, rather than an

extensive use of the range of

the instrument's possibilities, I hoped to put

the raw resources to personal

and much less trite or commonplace

application. This approach

was strongly reinforced by my past

experience, working

occasionally in studios other than my own. When one cannot use all the

available resources in a virtuosic way, one can

isolate a severely limited

range of possibilities, examine that finite range

to its reasonable limits, and

offer intensity born of familiarity, careful

selection, and thoughtful

application (i.e., virtuosity) from a different

perspective.

How the Mosaic Works

An essential

aspect of the visual mosaic is that the artist makes no

attempt to deny the nature of

the raw materials from which the work is fashioned. The mosaic resides in a

twilight world: that of stones which

are obviously just that, and

at the same time that of assemblies of these elements configured in

geometrical patterns or representational scenes.

The individual identity of

the smallest element of the work resists, to a

discernible degree, being

subordinated to the larger form, yet the larger

form would not have

palpability if it were not for that stone and the others

like it. For that very

reason, we can engage in moving our mental

attentions from the level of

the individual element, to the whole, and to the

stages between these

extremes, much as I have illustrated in the

example of the pyramid.

The Russian

formalist, Victor Shklovsky, has said, that the object of

art is to

estrange

or

defamiliarize; that

is, by disrupting the ordinary

modes of perception, art makes

strange the world of everyday perception

and renews the perceiver's

lost capacity for fresh sensation [Abrams,

166]. Shklovsky has also said

that the point of art is to make the stone

stoney [Scholes, 83]. The

mosaic does just that. By taking the stone out of its usual context and

placing it in one which not only calls attention to

the stone itself, but uses

the stone in a completely un-stoney way our

experience of the stone is

heightened. I would stress that the point is to

elevate to greater awareness,

not

stones,

but

experience itself.

An important

distinction between a visual mosaic and a piece of music is that

the former holds still while

the experience of it is structured by the

movement of the eyes of the

observer over the mosaic's surface. Music,

on the other hand, speeds by

in time essentially in the manner

determined by the composer. The

implications for this are considerable.

The Workings of

Elektronikus Mozaik

These are the

implications which I sought to exploit in

Elektronikus

Mozaik.

I have already

indicated my wish to focus the listener's attention

on timbre by means of

considerable restriction of the role of the other

parameters. The most important

restriction was the limitation of sound

objects to, at least for the

most part, only one approximate durational

value. By severely limiting

rhythmic activity to similar envelopes with

equal durations I hoped to

direct the listener to similarities and contrasts

of timbre. I felt that the

simplicity of the short durations would facilitate

immediate identification and

comparison [in the present] and, further, that

those short sounds which were

followed by silences would be conducive

to reflection upon what has been

heard [in the recent past].

The

principal constraint, from the standpoint of the manual

operation of

the instrument, was to limit myself to striking the keyboard

with the briefest possible stroke

and to using instruments with relatively

short attack and decay times. The careful selection and control of

spectrum, attack, and decay of individual points of sound is not unlike the

careful selection and grading of the pieces of stone that will be set in a

mosaic. The linear and simultaneous juxtaposition of the resultant

musical

colours and textures relate to the mosaic setting itself.

Although

Elektronikus Mozaik

might have been conceived as a

sonic analogy to a

visual mosaic, it is significant for the thrust of this

paper to point out that the

title is meant strictly to create an initial frame of reference for the

listener, rather than to provide an accurate accounting of

the provenance of the piece.

The title offers the listener guidance for the approximate placement of the

focus of the mind's ear at the outset of the

piece. By the same token, the

model of the mosaic may serve to

illuminate the processes in

music that may be somewhat more readily

identified in examining the

parallel visual domain. I present the

discussion in the context of

both media in the hope that, should what I am

saying not be entirely clear

in reference to music, it may be so in

reference to visual art and

that the reader's reflection upon the latter will

itself illuminate the

musical issues where I have failed to convey

successfully the idea

directly. This might be rephrased to read: in order

to offset the ease with

which discussions of aesthetic issues may go

greatly amiss, I approach

those issues by means of triangulation in the

hope of gaining greater precision.

Elektronikus Mozaik

is very much concerned with

the role of

expectation operating at very limited local levels as well as the

concatenation and integration

of these levels to produce many kinds of

potential mental

interactions (on the part of the listener) with the

processes of the piece. The

initial stage of placing the component points

of sound in their setting, and

a further means of offsetting the obvious

fresh-out-of-the-box quality

of my material, was implemented by the use

of multitracking. Caution

dictated avoidance of focus on obvious

harmonic or orchestrational

layers. Attention was given instead to simple

rhythmic/spatial distribution.

Because the

attention, or focus, of the ear (as well as the eye) is

drawn by those elements which

are most active, it is important that those

elements

not

of primary

importance be subordinated by making their

activity constant or highly

repetitious. To highlight or, more precisely, to

isolate the timbral qualities

as the principle focus of my material, I

attempted to limit the amount

of attention drawn to other parameters by

means of the following expedients:

Rhythmic

structure is limited to

simple regular subdivisions of the

pulse, producing a steady

stream of eighth notes throughout the piece.

Only slight violations of

this appear in the piece and these are limited to

the second section (of 6),

appearing in one voice only.

Harmonic activity

is limited solely to

octave and fifth relationships, with the exception of

semitones

briefly used approaching the end of the second section.

Frequency

range,

however, is

employed in a dominant way to define and

shape

sections of the work.

Melodic

activity could be considered to be

completely

absent with that same exception, one voice of the second

section.4

The harmonic and melodic restrictions had the added advantage

of reducing the characteristic stock-instrument quality by obscuring

formant cues or, as is particularly the case with electroacoustic

instruments, the lack of rich formants. The brief durations also aid a bit in

camouflaging the stock qualities, since steady-state conditions are

essentially eliminated and only the active processes of attack and decay

are

preserved.

Analytic

and Relational Mental Processes

To this point, my discussion has largely concerned what the music

does or does not do. But, as I have indicated, I am also very much

concerned about what the listener does in relation to the music. Earlier, I

said that I wanted to address my music to the primary focus of the

listener's analytic and relational mental processes. Allow me to explain

why I feel that it is important to describe mental processes in this way. In

the writings of many philosophers, psychologists, and others who would

try to understand the workings of the human mind, there is an

overpowering sense of the dichotomy that I have represented with the

words analytic and relational. David Loye presents a table of 52 pairs of

terms attributed to nearly as many authors describing what he calls the

two kinds of consciousness. I have selected those dichotomies which

especially well reflect my own sense of how this division functions

(although I

find those pairs that I do not list here also supportable):

| |

A |

B |

|

Observed

by |

Left

Brain Related |

Right

Brain Related |

|

Blackburn |

intellectual |

intellectual |

|

Bronowski |

deductive |

imaginative |

|

Bruner |

rational |

metaphoric |

|

Cohen |

analytic |

relational |

|

Dekman |

active |

receptive |

|

Hobbes |

directed |

free |

|

I

Ching

|

the

creative |

the receptive |

|

Lee |

lineal |

non lineal |

|

Levy &

Sperry |

analytic |

gestalt |

|

Lomas &

Berkowitz

|

differentiation |

integration |

|

Luria

|

sequential |

simultaneous |

|

Maslow |

rational |

intuitive |

|

Mills |

neat |

sloppy |

|

Neisser

|

sequential |

multiple |

|

Schenov |

successive |

simultaneous |

|

Schopenhauer |

objective |

subjective |

Figure 1: Adapted from Loye, p. 41

Those attributes in column A suggest a part of the mind which deals with

one thing at a time, stringing things out according to some kind of strategy

that pulls individual elements together according to some easily

comprehensible commonality: things are selected and spread out on a

table to be rearranged in a search for some order that satisfies.

I

have

borrowed from Cohen in choosing to refer to this aspect of consciousness

as analytic. The attributes in column B are very different: these have to

do with large amounts of things swept up simultaneously, not considered

separately but swallowed whole. The considerable degree of voluntary

control of the rational aspect of mind is exchanged for the ability to scan

enormous amounts of detail in many ways at once. This

I

am calling the

relational

aspect of consciousness.

As a composer,

I

am not particularly concerned about where in the

brain these activities happen, but I am compelled to believe that these

levels of mental activity are simultaneously operative when we listen to a

piece of music (and when we do everything else).

I

would add that while

there do indeed seem to be two such conscious functions,

I

am

convinced that these very different kinds of mental responses to music

(and to everything else) talk to each other. Moreover, either there is a

variety of blends of these qualities or there is a continuum of levels that

spans

the extremes.

I

stress the importance of the two kinds of consciousness and their

role in musical experience because

I

believe that the most satisfying

aspects of the experience of music are, in fact, the sensations of our own

minds working. Music's special quality is not found in the physical

dimensions of the sounds so much as the fleeting quality that makes the

mind grasp for impressions, engaging the processes of exploring,

examining, turning, pondering. We do not savor the perturbations in our

ears; we savor our own reconstruction of the gossamer, ephemeral

qualities that have flashed through our consciousness, leaving only what

we

thought about them in their wake.

Impression upon impression offers a changing view of the

perceived experience. For each individual the order, kind, and depth of

impression will vary greatly. But let me try to give an example, using the

opening of

Elektronikus Mozaik,

a portion of the piece that is really a

microcosm of

the processes of the work as a whole.

An Example

The functions of the beginning section are to attract attention to an

aspect of the music and to hold that attention. It is easy to do the first,

but as time passes,

holding

attention requires increasingly greater provision.

The piece begins with a moderately loud burst of sound which allows

little doubt that the piece has begun. It is perhaps useful that this device

draws attention although I believe that the average audience member will

give the composer the benefit of the doubt and attend for at least the first

few seconds. One is conscious of approximately the following sequence.

Although I must, of course, use words to convey these impressions,

I

believe that non-verbal thoughts are more frequently the agents for

handling this

kind of information in the mind:

a.

rapid, free articulation on one high pitch

b. the

free rhythm is resolved gradually to regular

pulsations

c.

the pulsations gradually sort themselves out into

specific spatial locations

d.

the unisons gradually transform to octave and fifth

relationship with the original pitch

e.

a consonant tone emerges and overwhelms the other

activity; there is a sense of

anticipation

f.

the tension of the anticipation is resolved by an

entry in

the lower register and that entry generally

releases

tension by means of a slower, much less driving rhythm,

and a less

strident timbre.

There is nothing very remarkable about any of this, except that its genesis

was the desire to attract and hold the attention of a listener. The holding is

attempted by beginning very simply and then gradually adding

- in a number of senses and more or less simultaneously - greater activity

and complexity. The key word is gradually. That is one of the principal

sources of the continuity that engages and holds attention. If numerous

gradual processes are underway at once, there is a greater likelihood

that one of

them will draw the precepent into the piece. When fatigue, or

other stimuli cause that line of eventfulness to be abandoned by the

listener, there are others waiting to draw and hold the attention. The

mind seems rarely to remain for very long in its attention to a single thing,

but moves rapidly from aspect to aspect. Attention is, in essence, held if

only the mind turns its attention to the same aspect frequently, comparing

the

present state of the aspect to previous assessments of its states.

At work here is the most significant mechanism of music. That

mechanism is

expectation.

If a work raises no particular expectations for

the percipient, he/she has little more involvement than a moment-tomoment

sensation of the physical properties of the work. But if a

sufficient accumulation of experience suggests one or more impending

possibilities, mental activity directly related to the experience of the work

can move beyond relational mental activity to analytical [asking where is

the process going? when will it get there? is it indeed a simple process or

are there new aspects emerging?]. If the mind is drawn to recalling what

has

already happened, comparing that to what

is

happening, in order to

consider possibilities for what

will

happen, the listener is involved well

beyond simple moment-to-moment monitoring and is involved

simultaneously in at least three aspects of the work at once. The

percipient is taking an active, rather than passive, role in the work. It is

that

activity that comprises attention.

Another Example

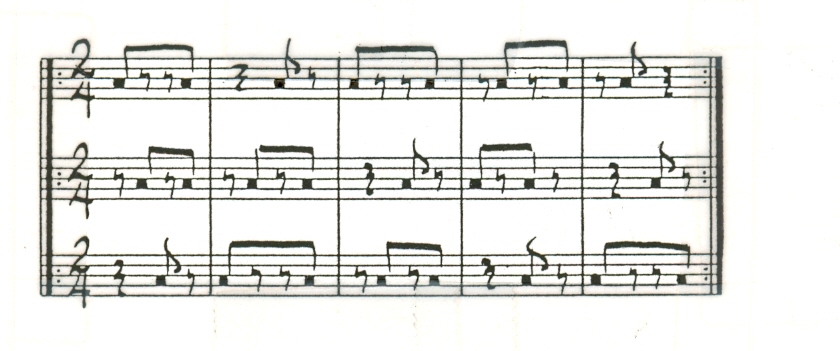

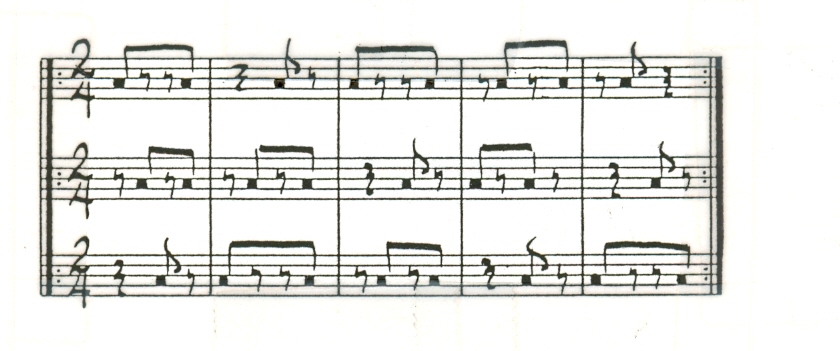

The following excerpt, owing to its higher information potential

than the opening of the piece, is more demonstrative of what I believe is

the kind of exploratory process that we use in listening to a piece of

music. Figure

2 is a representation of a pattern used in the piece.

Figure

2: Hocket Pattern from

Elektronikus Mozaik

Figure

2: Hocket Pattern from

Elektronikus Mozaik

I refer to this kind of material as hocket although I tend to use it

monotonally and in much longer series of repetitions than was the case

in the work of the 13th- and 14th-century composers who drew my

attention to the possibilities of the technique. I have chosen this pattern

because it is a very important one for the character of

Elektronikus

Mozaik

and because it is a relatively direct example of the issues that I

wish to illuminate. Needless to say, the aural experience of this pattern is

very different from the reading of it on the page. A first aural encounter

with the repeating pattern might have something like the following

chronology of

mental activity:

a. In

the first moments there is a sense of the whole as an

agitated

jumble of sound, and there is little if any

differentiation except a general awareness of a more or

less

narrow range of timbre and little variety in sound

object durations.

a.

At the same time, there is a vague

awareness that the

sounds,

while generally mechanical and repetitive, are

subtly

varied; the sources are not simple, there is an

organic quality to the sound.

b.

Then an increasing awareness of a regular pulsation

as a composite of the sounds coming from various spatial

locations

b. Then

an increasing awareness of a distribution of the

sounds

over a number of spatial locations [it is difficult to

know

whether one of these observations precedes the

other or if the two are essentially

simultaneous].

c. A

sense emerges that there is interruption of identifiably

the same

timbre coming from fixed spatial positions, this

hypothesis is tested and confirmed by isolating at least

one of the apparent locations.

d. Once

the apparent position in space and timbral

identity

have stabilized, there is an increasing sense that the rhythm has a

complex but regular pattern and this too

is tested and retested;

perhaps confirmed by following the

7- or 8-note rhythm of

a single spatial position only, or by identifying a recurring

juxtaposition of two or three voices at one particular point in the

pattern (for example the last three eighth notes followed by the first

three eighth notes

of the combined

pattern). Because the loudness of the

individual attacks is

quite free of the pattern, made up as

it is of sounds with a

general timbral envelope and

attacks at only

approximately regular intervals, the task of

verifying that a

regular pattern is present is not trivial.

Thus perhaps the

observer will not entirely confirm that

there is

a regular pattern if the issue does not seem

sufficiently important or if the task

is beyond the analytical

skills of

the listener. The pattern is sufficiently complex that the listener may

nearly or entirely sort it out only to

lose it,

doubt the presence of a pattern, and then begin to

analyze it again.

e. Even

if space, timbre, and rhythm are analyzed

completely, there is the variance of attack spectrum and

loudness, combined with the slight deviance of attack

regularity, that will

invite speculation and testing.

Moreover, the mind goes

back over the issues already

examined to determine

if change has taken place.

Consequently, even if

the pattern was not to change for

many

repetitions, there is enough here to engage the

willing mind for some considerable

length of time.

If the

above at all represents what a listener might think, I would

suggest that there is a

general progression of thought from a hasty

assessment that the sounds

are only very loosely organized, to a

considered judgement that

they are rather highly organized. The

sequence of thinking moves

from (a), which is almost entirely a relational

impression to (b), an

essentially relational impression subjected to

rudimentary analysis. (c)

is more analytical than (b) but still rather

rudimentary. But by the

time we have arrived at (d) and (e) [a time span

of a score to several scores

of seconds], the levels of thinking are highly analytical and we are into a

kind of thinking that may emerge, for a time, very much into the foreground

of awareness of the listener. I would draw

attention to the fact that

there is sufficient involvement to provide a

significant aesthetic

encounter with the passage if the listener merely

forms

some

sense that there

is or may be a pattern and undertakes some

degree of testing the

hypothesis. That the listener comes to a successful

conclusion [for example:

that (d) is regularly patterned and that (e) is not],

is not at all necessary.

In

Elektronikus Mozaik,

sonic colors are worked

into variously

similar and contrasting rhythmic contexts intended to encourage the

listener to move his/her

mental focus among the larger and smaller levels

of structure, lingering

where there is some sense of coherence and, in

particular, continuity at

any of these levels. At the micro-levels of the

work, the richness and

variety of the individual points is meant to attract in

one way or another the

listener's attention, while the macro-levels,

comprised of interwoven

streams of points, merge into structures which

are meant to fully engage and

hold the listener's attention.

The

micro-levels are not less important than the larger levels,

however. Byzantine mosaic

art, which reached perfection in the 6th

century, Hagia Sophia,

particularly exhibits small stones which were set

by hand in the damp cement

mortar, and the resulting irregularities,

causing the facets to

reflect at different angles were essential factors in

the glittering effect of the gold

backgrounds. It is just this kind of subtle

but highly

kinetic quality that I feel is essential as a supplementary or

background process in art.

It brings additional vitality to the experience.

Moreover, the interference

with the more stable features prolongs, and

may heighten, the richness

of the analytical processes. Of course, in

sonic terms there is no

parallel change of perspective, but the essentially

capricious response of a

keyboard with activated touch sensitivity can

produce this same kind of

subtle but highly kinetic quality in the timbral

domain. While a repetitive

pattern is, on the level of rhythm and general

colour, constant, the

varied attack qualities call attention here, then there,

to provide a highly active

context, making the repetition much more

durable.

I do not

pretend to have covered in the above summary the full

range of

possible thought processes going on in the mind of a listener to

this

passage. While thinking in repetitive loops and jumping from place

to

place among all or most of the modes delineated above, the mind of

the listener will additionally

flit through such observations as:

that

sounds like a door bell...the loudnesses are varying

without

apparent pattern...this rhythm is repetitive -will

there be a logical resolution, or will the pattern

fade away, or will it go on annoyingly

long?...

And

even:

did I turn

off the stove before I left home?...the man in

front of me

has a bad cold...this seat is hard - perhaps I

will be more comfortable if I cross my

legs...

But if there

is sufficient matter in the music to attract the attention [mostly

happening at the relational

end of the thinking spectrum] and hold it [mostly happening at the analytical

end], such thinking will occupy a

sufficiently large portion of

the mental processes to register a significant

and positive experience.

The

Point of These Points of Sound

What is to

be gained in all this effort to register for listeners

significant and positive

experience? What is the significance? Before I

try to answer that, it is

important that we have a clear picture of what the

brain is initially making of

these stimuli. John Bransford and Jeffrey

Franks [Campbell, pp. 224-5]

have amply demonstrated that the

individual tends to

construct complete meaning out of disconnected

elements and it is this

constructed meaning that is remembered. During

complex experience, the brain

goes to work on information while it is

being stored in memory,

interpreting, drawing inferences, making

assumptions, fitting it into

a context of past experience and knowledge already

acquired. When the information is recollected, the elaborations

added by the brain may behave

like a memory, so that people have the

mistaken impression that the

extra information is part of the original

message.

Once placed

in memory, observed information and impression

information are not easily disentangled. Various strands of meaning can

be so thoroughly fused

together that they may not be capable of being

unraveled. This knitting of

parts into one whole experience appears to be

a one-way process, not

reversible without conscious effort, and not

always then. For the composer,

it is important to know that what is likely

to be the

sense

of what happened

is much more important than what

actually

happened. Two sentences from Percy Scholes'

Oxford

Companion to Music

beautifully express the implications, for art, of this aspect of the mind: In

science, things are what they are. In art, things are

what they seem.

Jeremy

Campbell [p. 227] remarks that while it may seem at first that man is a rather

flawed creature to possess as unreliable a memory

as the above implies, on

further consideration, a mechanically accurate memory has only surface

conveniences. He says that human beings are not designed to function

uniformly. Their success as a species arises in

part from their lack of

specialization. Mechanical accuracy is not what we

are best at, and it is not

what people, generally speaking, want to be best

at. The brain is not a

device for processing information in a one-dimensional,

linear fashion only. Unlike a computer, which is subject to

very little noise in the form

of electrical interference, and which works by

performing a long chain of

simple operations at high speed, the brain is

both noisy and slow, but it

uses its colossal number of components to pass information along many

different channels at the same time. The

brain is probable rather

than certain in its actions, arriving at many

answers, some more nearly

correct than others, and these answers are

modified continually by feedback of

new information.

If our minds

are not especially suited to accuracy, why is it that we

are motivated to engage in

exploring, examining, turning, pondering?

After rigorous physiological

studies, Jerzy Konorski [p. 37] concluded that

the active questing of the

mind is a basic survival mechanism, that it operates on all levels from the

neurons upward, and that it takes two

main forms: searching

behavior and exploratory behavior. Searching

behavior is the response to

hunger, sexual desire, the need for sleep.

But exploratory behavior is

unspecific, we are simply urged to move, look,

hear, feel, by a sheer need

for stimulation. Konorski asserts: "these

stimuli are almost as

necessary for ... well-being as is food or water." But

as a

chateaubriand a la bernaise

and a bottle of 1961

Mouton Rothschild

offers a more satisfying experience than gruel and water (even though

the gruel and water might in

fact better serve the interests of the survival

of the heart and kidneys),

stimulation that has potential for discovery of

similarity,

interrelationship, complementarity, or continuity offers far more

satisfaction than random or

monotonous stimulation.

There are

times when our very objective is to exercise this feature

of mind in particular. We

call this activity "play." Play is at the very core of

artistic experience. Johan

Huizinga (pp. 7-19) lists the elementary

features of play as 1)

voluntary, 2) clearly separated from other life activity

in space and time, 3) not

real, but 4) serious (sometimes profoundly

serious), and 5) distinctly

capable of repetition of the whole or any of the

parts. The import for music of

all five points is too extensive to deal with

here, more than to say that

the study of play has much to tell us about

how art works. The most

important aspects of play are how the child

chooses to structure the progress

of play.

With no pun

intended, the theatre may also be a very useful source

of this kind of knowledge.

Some years ago, while serving as an instructor

for an electroacoustic music

workshop in France and following a

performance of one of my tape

pieces, fellow instructor Guiseppi Englert

observed,

"Oh, you do

dramatic

music. I don't do

dramatic music any

longer." In fact, I had never thought of using that adjective to describe what

I did with the music, and at first I thought the description rather a

negative one. Upon further

reflection, I thought it a particularly apt

description. Guiseppi did not

say, program music, he used the word

dramatic. I am not seeking to

tell a

story,

but I certainly am

struggling to make

effective use of the basic structural components that one would find

in a drama: a specific arena

for action, distinguishable protagonists that

act and are acted upon, a

movement toward a variety of likely but

importantly different

possible outcomes, and a resolution of the tension,

created by the foregoing,

through implementation of an outcome that

seems as appropriate a

consequence of the sum of the action of the

piece as possible.

Perhaps it

is appropriate to close with the observation that both the

word music and the word

mosaic derive from the Greek

mouseios or

mousikos meaning

pertaining to the muse(s). The English word to muse,

and the Greek word for those

Muses who were such great patrons of the

arts, are cognates of an

Indo-Germanic root word meaning to think.

Mozaics, music, art: these

are for thinking. The exploring, examining,

turning, pondering stimulated

by an effective work of art is not the

means

to an end, it is the

end

itself.

Bibliography

Abrams, M. H.,

A Glossary

of Literary Terms,

4th ed., Holt, Rinehart and

Winston,

New York, 1981.

Campbell, Jeremy,

Grammatical Man: Information,

Entropy, Language, and Life,

Simon and

Schuster,

New

York,

1982.

Huizinga, Johan,

Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play

Element in Culture,

Beacon Press, Boston, 1950.

Keane, David, "A Composer's Approach to Music, Cognition, and

Emotion,"

The

Musical Quarterly,

LXVIII/3, July,

1982, pp. 324-36.

_____________

, "Computer Music: New Tools for Old

Problems,"

The

Humanities Association Review,

XXX/1-2, Winter, Spring,

1979, pp.

103-13.

_____________ , "Music, Words, Energy: A

Dynamic Framework for the Study of Music,"

Cognition and Perception,

(in press).

_____________ , "Some Practical Aesthetic

Problems of Electronic Music Composition,"

Interface,

VIII, 1979, pp. 193-205.

_____________

,

Tape

Music Composition,

Oxford

University Press,

London,

1980.

Konorski, J.,

Integrative Activity of the Brain: An Interdisciplinary

Approach,

University

of

Chicago

Press,

Chicago,

1967.

Loye, David,

The Sphinx and the Rainbow: Brain, Mind and Future

Vision,

Bantam,

Toronto,

1984.

Scholes, Robert,

Structuralism in Literature,

Yale

University Press, New Haven,

1978.

1

A recording of the work discussed in this paper, Elektronikus

Mozaik, is available on the disc

David Keane: Aurora

[Cambridge Street Records 85021. The disc may be purchased [$11.00

U.S., postpaid or 513.50 Canadian, postpaid) by writing to the Canadian Music

Centre Distribution Service: 20 St. Joseph Street, TORONTO, Ontario M4P 1Z5.

2

If

telling people what one did in making a piece of music is the stuff of

dissertation appendices, why am I writing this paper? The answer is that my

objective is not to explain Elektronikus Mozaik, but to try to bring

out into the light of day some things about me as a composer and a listener

for me. Readers' responses to this paper are the means to my finding how my

perceptions relate to those of others. I

hope that my reasons for wanting to know this are made apparent by the

text of this paper.

2

If

telling people what one did in making a piece of music is the stuff of

dissertation appendices, why am I writing this paper? The answer is that my

objective is not to explain Elektronikus Mozaik, but to try to bring

out into the light of day some things about me as a composer and a listener

for me. Readers' responses to this paper are the means to my finding how my

perceptions relate to those of others. I

hope that my reasons for wanting to know this are made apparent by the

text of this paper.

3 Whether

a composition is performed, broadcast, recorded, or published is determined by

how other people respond to

the work. And should the work be performed, broadcast, recorded, published or

otherwise disseminated, the life, one might say, of the work is rather dependent

upon how those who hear it respond. Composers who have no regard for other

people's responses are outside my understanding. Those who do have such a

regard, must admit that the discrepancy in perception observed here is a serious

problem, requiring compensative measures.

4The exception of the

second section seems to loom rather imposingly in this summary. While every part

of a piece of music - its consistencies, its regularities - makes it what it is,

there is no special significance of which I am aware, in the violations of the

general principles of the piece in the second section. What I did there seemed

an appropriate means for increasing tension and so it remains a part of the

piece. It is only in my subsequent analysis that I find the section at all

anomalous.

![]()