Harmonics

present in a sung tone can be individually reinforced or amplified and

perceived as discrete pitches (sounding like whistles) as tongue and/or lip

action changes the shape of the vocal tract. The sung fundamental is

produced using Western art music phonation, usually without vibrato so that the harmonics

nasalization, which tends to filter

out the fundamental and focuses greater attention on the harmonics.

The

examples discussed below demonstrate harmonics reinforced over either a single pitch

or a continuously changing fundamental. One or more harmonics may be individually

reinforced over a single pitch, both ad libitum and

as a designated, specific harmonic. The vocalist's skill may even allow the

composer to write a melody with the harmonics. A

rapid movement through a series of harmonics will probably shift the listener's

attention to timbral changes rather than

recognition of specific pitches. A shimmering effect may result from rapid

oscillation between two adjacent harmonics (see below).

Improvisation

over a unison fundamental pitch represents one musical context for reinforced

harmonics. Early improvisations done by the Extended Vocal Techniques Ensemble

during rehearsal sessions were frequently structured in the following manner: A single

pitch comfortable for both men and women was chosen, usually F# (184 Hz)3 or G (196 Hz) below middle C (261 Hz), and sustained without

break by staggered breathing. An approximate duration was set, perhaps 5-10

minutes, during which an emphasis first on the

lower harmonics was to gradually progress to the inclusion of higher harmonic reinforcement

within a specified dynamic structure of perhaps soft to loud. Tape recordings

of a number of these early sessions are filed in the archive of the Center for

Music Experiment

at the University of California, San Diego.

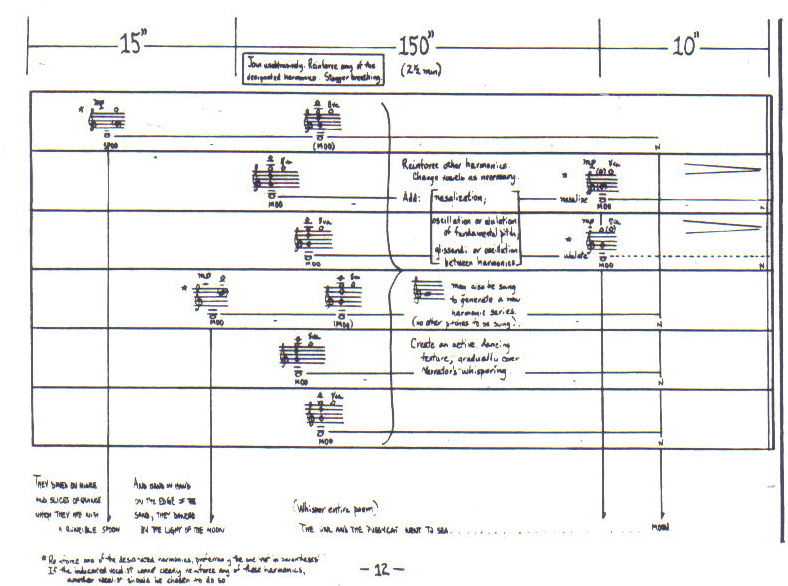

The first notated composition written for EVTE, The Owl and the Pussycat by Deborah Kavasch, includes an improvisatory section on a unison G (196 Hz) built on the last word of the text, " moon." The score (Figure 1) indicates that only those harmonics in a fifth or octave relationship to the fundamental are to be reinforced at first: others can be reinforced later. The instruction "Create a dancing texture, active" is made possible by including several techniques in combination with or as a variation of the basic individual harmonic reinforcement. The "dancing" characteristics arise principally from those techniques which rapidly change the pitches of the harmonics or which interrupt or alter the fundamental and harmonics. The term "glissandi" refers to ascending or descending sweeps through a series of harmonics. An oscillation between harmonics, which is subsequently referred to as " harmonic oscillation," results from a backward and forward movement of the tongue and is quite effective when produced rapidly between two harmonics. If the fundamental pitch is low, two high adjacent harmonics are easily oscillated: if the fundamental is high, two low adjacent harmonics respond well. Oscillation of the fundamental, similar to vibrato, changes the pitch of the fundamental at regular or varying speeds, causing the reinforced harmonic to change pitch at the same rate. The rapid, repeated note effect of ululation (see III. Ululation) rather evenly and quickly interrupts the fundamental, these pulsations help emphasize the harmonics as well. When another voice adds a fundamental pitch one octave higher than the original fundamental, it generates a new but closely related series of harmonics which increases the complexity of the texture'4 (Tape Example 1).

.

Figure 1: Reinforced

harmonics in The Owl and the Pussycat by Deborah Kavasch

(Tape Example 1)

Another

use of reinforced harmonics over a drone appears in Sweet Talk by Deborah Kavasch. In one

section the harmonics are specifically those which result from a slow glide

through the vowel sounds of the syllable "beau" (as in

"beautiful" ), i.e. a slow glide between

[ i ] and [ u ]5. The duration and dynamics of each entrance are notated,

showing specific

breathing points (rests) and definite, perceivable entrances (Tape Example 2). Although a drone results from the continual overlapping of

entrances, the whole is not perceived as a

smooth, unbroken fundamental as in the previous example.

One further

example involving harmonics reinforced over a single pitch drone illustrates

a slightly different usage involving different rates of change in harmonics generated

from similar texts. In the opening section of Deborah Kavasch's Requiem. (Tape Example 3), the

upper three taped voices sing one syllable per measure (B 247 Hz); the upper

three live voices sing the same text on the same pitch at one

syllable per two measures. Harmonics appropriate to each vowel are reinforced without

vibrato. This emphasis of a particular harmonic determined by the specified vowel aids in

tuning the unison and provides a type of countermelody to the drone, in this instance two countermelodies. Amplification with microphones for each

vocalist aids in projecting the harmonics.

Nasalized,

reinforced harmonics ad libitum on specific pitches provide a striking beginning

to Edwin London's Psalm. of These Days II (Tape

Example 4). The intelligibility of the word "Lord" varies due to the

changing harmonics as well as its long duration (three measures).

Although the initial unison D# (311 Hz) expands to a four-note chord spanning a

minor seventh, the fundamental pitches together with their harmonics of the " r" in "Lord" are still close enough to create a rather

dense texture. Compare this with a later example of

reinforced harmonics on the same word, in which the fundamental pitches are spread over approximately a two

and one-half octave range (Tape Example 5).

Both

nasalized and non-nasalized harmonics are reinforced over slowly gliding fundamental

pitches against a background of computer-generated tape sounds in Joji Yuasa's My Blue Sky in Southern California (Tape

Example 6). The fundamental pitch is chosen at random

by the vocalist and gradually ascends or descends as indicated in the graphic score.

Unusual effects are achieved by pitch changes in both the fundamental and

harmonics which may move at varying rates in similar or

opposite directions to each other. In order to be

easily heard in this very loud and dense section, the vocalists tend to choose and

nasalize the higher harmonics (towards UP, creating a

rather buzzy, piercing quality in the long pitch glides.

In another

section of the same composition, the oscillation between several pairs of low

harmonics of a rather high fundamental (approximately A 880 Hz) is heard

against a sparse background of very soft clicks and other similar

short, nonpitched sounds (Tape Example 7). The

higher the fundamental, the more difficult it becomes to reinforce its highest harmonics.

In this instance, the oscillations occur between various combinations of the first three

or four harmonics (including the fundamental), which may acocunt

for the pulsating whistle effect during

part of the example. Oscillations between low harmonics (of a high or low

fundamental) may also be more striking because of the greater intervallic distance

between the pitches of the lower harmonics. For example, the oscillation

between the (1) fundamental (or first harmonic) and second

harmonic covers one octave; (2) second and third

harmonics covers a fifth; (3) third and fourth harmonics covers a fourth; (4) fourth and fifth harmonics

covers a major third, and so on, the distance always smaller.

At one point in Deborah Kavasch's Tintinnabulation, harmonic oscillations occur simultaneously in several voices. The fundamental pitches are each a half step apart (F 350 Hz, F# 370 Hz, and G 392 Hz) with the harmonic oscillations of each pitch determined by the same [ill] vowel alternation (Figure 2). Such a close pitch combination results in an overall pulsating or shimmering effect rather than the perception of individual harmonics (Tape Example 8).

Figure 2: Harmonic oscillations in Tintinnabulation by Deborah Kavasch

A

vocalist's increased skill and accuracy in reinforcing harmonics allows the

corn-poser to specify more particular uses. Simple melodies are possible,

especially when using the lower three to three and one-half octaves of

harmonics (first seven to twelve harmonics). Novices can quickly learn

to reinforce the melody of the traditional bugle call, "Taps," which uses a one-octave span of harmonics, specifying

the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth

harmonics. The lower three octaves of harmonics are more favorable for writing melodies based on reinforced harmonics because it

is easier to distinguish between the lower

harmonics than between those which are less than the interval of a second or

third apart. Generally, the lower the

fundamental the more harmonics can be reinforced with clarity. If the

fundamental is too low, however, the lowest harmonics become difficult or impossible to reinforce. Although this varies with

the individual voice, a comfortable lower

limit for a fundamental pitch within which the vocalist, male or female, can

clearly reinforce the lowest harmonics

can be set at approximately F 175 Hz (below middle C). Fundamental pitches lower than this

arbitrary point are increasingly more favorable for the discriminatory reinforcement of higher

harmonics, particularly those in the third and fourth octaves above the

fundamental.

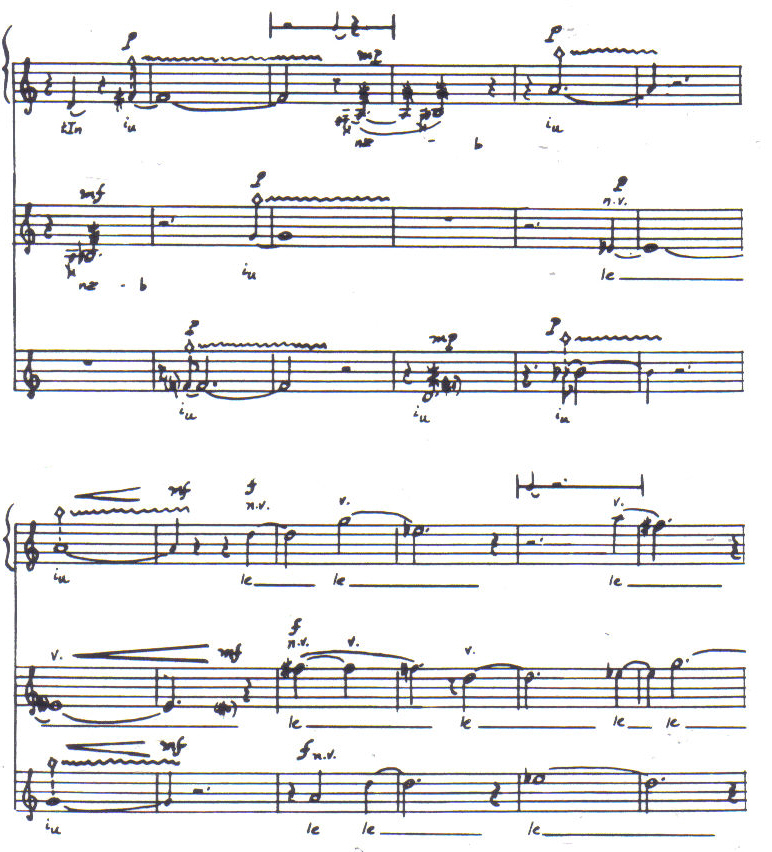

A melody

formed by specified reinforced harmonics appears in the second "Hosanna"

of the Kavasch Requiem. (Tape

Example 9). Against a taped background of four voices

singing for the most part in octave F#'s (185 and 370

Hz; note that a strong C# 1108.5 Hz is generated by the [a] vowel), the vocalists

form melodic phrases using certain of the lowest seven harmonics of three F#'s

(92.3, 185, and 370 Hz) and two C#s (138.5

and 277 Hz). The score shows regular noteheads

(stems down) for the sung fundamentals and diamond-shaped noteheads

(stems up) for the harmonics. For greater clarity and reliability,

the melody of harmonics is always carried by at least two voices; all voices

are amplified with microphones. The use of voices on tape singing a slowly

paced text to a very simple harmonic structure provides pitch stability

and avoids interference with the audibility of the harmonics produced by the live

performers but helps to mask vowels resulting from reinforcing the specified harmonics of the

live portion (which do not form intelligible words). The harmonics form a melody quite

similar to that which is sung in the first "Hosanna" and should, by association,

be more easily recognized or perceived by the listener than a new melody

would be.

Reinforced

harmonics is one of the few techniques which does not

always, or even most often, require individual or general microphone

amplification. Especially when reinforced over a drone, the harmonics are often perceived as

non-directional, filling the entire space as though surrounding the listener. The

fundamental, however, is usually directional and

perceived as originating in one particular spot. Amplification is recommended when the

harmonics must be heard above a very loud or dense texture, or for better projection of specific melodic

passages.

Ululation

The

technique of ululation is perceived as a rapid, relatively even interruption of

the basic sound. It is articulated by aspiration (puffs of air or "his") or glottal stops and can be applied to virtually

any sound, voiced or unvoiced. Children often ululate

a loud, nasal

sound to imitate the firing of machine guns or the bleating of sheep.

Several

forms of ululation are discussed below: (1) ululation of a single pitch or series of

pitches; (2) nonpitched ululation, or an ululated

whisper; (3) ululated glottal clicks, referred to as "glottal whisper;" and

(4) cross-register ululations, i.e., a very rapid alternation

of two pitches produced by a rather loud ululation in the area of a natural register break.

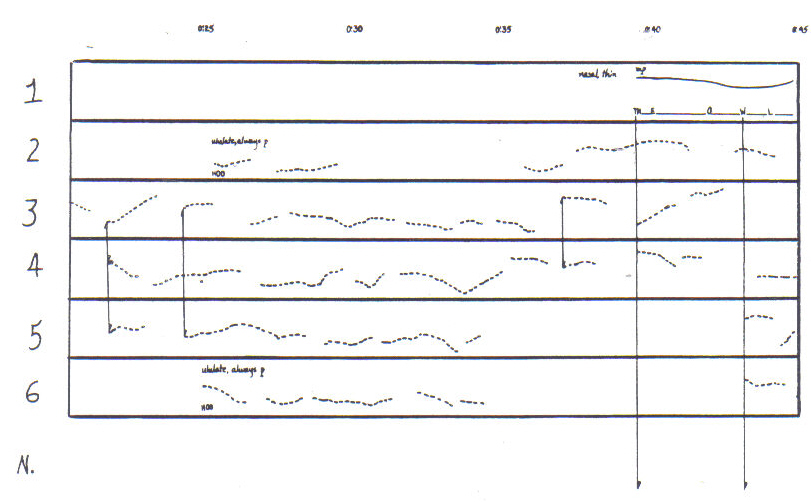

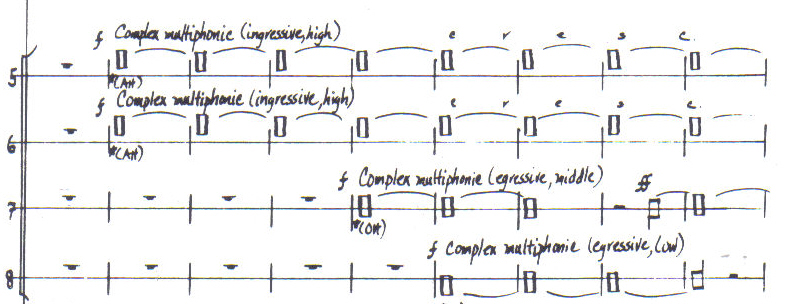

The opening section of The Owl and the Pussycat, preceding the narrator's first entrance, builds a gradually thickening texture of soft ululations. The score (Figure 3) indicates the progression of time in minutes and seconds and shows a graphic outline of approximate pitch levels and directions. Each box represents from top to bottom the high to low pitch range of the individual vocalist. The taped example (Tape Example 10) demonstrates the effect of several voices softly ululating an aspirated [u] in relatively low pitch ranges. The next example (Tape Example 11) includes ululation of some of the vowels and consonants of the word "pussycat." Appropriate vowels and consonants are deliberately aligned with similar ones in the narrator's text. Ululations can be used not only with short or long passages of a single vowel or to extend and color individual words but to articulate melodic phrases as well. The vocalists ululate several short melodic fragments set to the words, "0 lovely Pussy," "0 Pussy, my love," and " What a lovely Pussy you are." This 90-second section gradually expands in total pitch range and density, and ends with a sudden shift from soft to loud ululations. The taped example (Tape Example 12) is excerpted from the first part of the section.

Figure

3: Ululations in The

Owl and the Pussycat (Tape Example 10)

Ululation

of an unvoiced whisper is used in the "Lacrymosa

dies illa" section of Requiem. In this

section the unvoiced sounds are divided into four categories: (1) a straight or

uninterrupted whisper; (2) measured (sixteenth-note) pulsations or aspirations of a

whisper; (3) ululations of a whisper, which are faster than the pulsations and

result in an almost shivering sound; and (4) measured or

unmeasured "glottal whisper," a term which refers

to a rapid series and/or ululation of glottal clicks. The ululated whispers attempt to

support the imagery suggested by the text (" A day of tears is that day" ) (Tape

Example 13).

The latter

part of Example 13 includes a soft ululation of two alternating pitches. This sound may

be related to the production of a glottal whisper to which voice is added. Although it can be

produced throughout most of the egressive singing

range, it is usually referred to as a cross-register ululation. This type of

ululation usually settles into the interval of a third and is most easily produced on the

vowels [i] and [u]. Because it is not as reliable

as the simple ululation or the louder cross-register ululation, it should be allowed a

certain amount of preparation time. It is least tiring in the lower female

range (approximately middle C to C 526 Hz). (As is true of

certain variations of the EVTE's techniques,

the soft cross-register ululation has been perfected by only one member of the ensemble and is probably less

likely to be produced by a majority of vocalists.)

A more

extended use of the soft cross-register ululation appears in Roger Reynold's A Merciful Coincidence. In Tape

Example 14, the ululations cover a wide pitch range and appear as background material

near the end of the piece. The designation "soft" in the term "soft

cross-register ululation" refers more to the physical sensation of the vocalist

in producing the pulsation, or interruption of the sound, than to the actual

dynamic level. In this example the higher ululations become much louder but

are still softer than a regular cross-register

ululation at a comparable pitch level.

The term

"cross-register ululation" refers to an ululation produced in the

area of a natural register break6. It results in a rapid

alternation of two pitches, which creates the illusion of two pitches ululated

simultaneously. The intervallic distance between the two pitches

varies with the individual vocalist but usually falls into one of two categories. The first

category emphasizes narrow intervals, i.e., approximately a minor second to a fifth. The

intervallic distance can be controlled so that either one specified interval or

a continuous glissando from narrowest to widest interval (or vice versa) can be

produced. The glissando appears to be most easily produced by the

upper pitch, which moves towards or away from the stationary lower pitch.' This

glissando of one of the pitches is best controlled in the register break around middle C. The

second category emphasizes wide intervals, i.e., approximately a sixth to an octave

or ninth. There does not seem to be the same degree of intervallic control possible in the wider

cross-register ululation, which generally

locks into one interval. This type usually occurs in either the male or female voice around the middle C register break area. Either

type of cross-register ululation may occur in

male or female voices but both types do not generally occur in one voice.

Cross-register

ululation, as described above, requires more energy than simple ululation

and is necessarily rather loud. It sounds particularly loud in the male voice since the

first register break at which it can be produced includes pitches fairly high in

the male chest voice range. For the same reason,

cross-register ululations in the female voice around the

second register break area are usually extremely loud. Ululations

crossing into the whistle stop area,

however, are often much softer. Those

cross-register ululations which occur higher in the voice are usually more tiring

than the lower ones and should be used

with consideration.

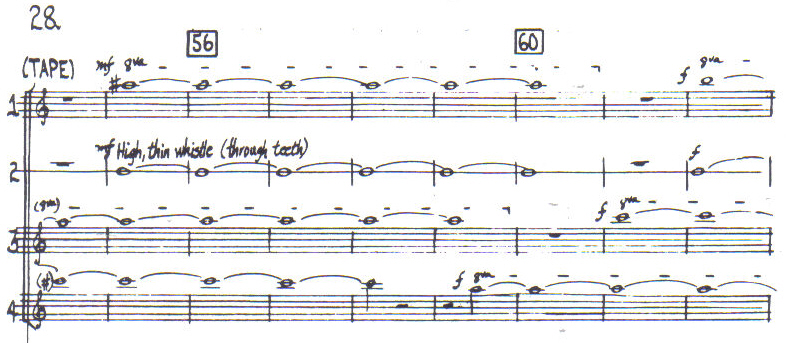

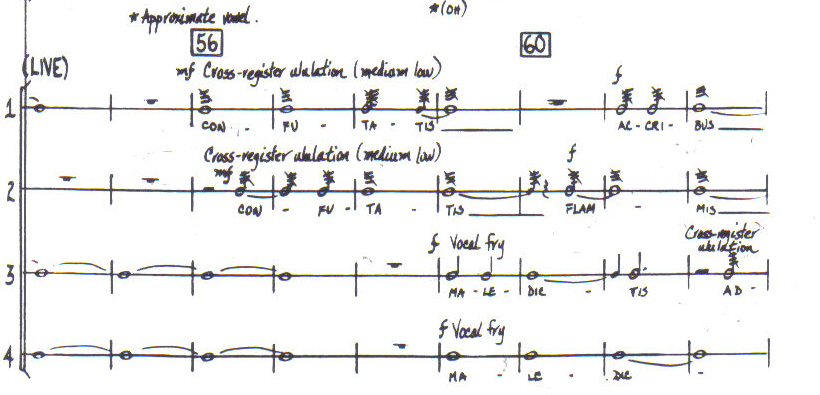

Both simple and cross-register ululations enhance the text of the " quantus tremor..." ("how great a quaking..." ) section of Requiem. A total of eight voices produces the effect of many more, an effect due both to the pulsations and to the extra number of pitches generated by crossing registers, i.e., alternating two pitches (Tape Example 15). A later example (Tape Example 16, Figure 4) combines several other techniques with cross-register ululations which are indicated by a general pitch level and which end in a quick upward glissando.

Figure

4: Cross-register ululations combined with other extended

vocal techniques in Requiem by Deborah Kavasch

(Tape Example 16)

Ululations

form a major portion of Tintinnabulation. The last section emphasizes high

cross-register ululations alone and in combination with high, wide vibrati and trills on glockenspiel bars (Tape

Example 17).

Tape Example 14

(from Reynold's A Merciful Coincidence), cited

previously to illustrate soft cross-register ululations, also provides an

example of a loud cross-register ululation.

Although the vocalist is probably not crossing registers at all times during

the ascent, the overlap of registers seems to be greatly

expanded with an overall effect of a continuous

glissando of alternating pitches.

Vocal

Fry

Vocal fry

is perceived as dry, clicklike pulses and is often

used to imitate the opening of a creaky door (hence, another common

designation as " creaky voice"). The pulse rate

of vocal fry can be controlled to produce a range from very slow individual clicks to a

stream of clicks so fast that it is heard as a discrete pitch. It can be

produced both egressively (exhaling) and ingressively (inhaling). The individual vocalist may find one mode

easier to control than the other in terms of such parameters as pulse rate, dynamics,

and pitch. The term "pitch," as used here in relation to vocal fry,

refers to the range of perceived pitches rather than to any implication

regarding the mode of phonation. Egressive and ingressive vocal fry can

greatly expand the practical pitch range (singing and -

speaking) of the individual vocalist, male or female.

Egressive vocal fry can be controlled to merge with and extend

downwards the lowest part of the egressive

singing range. It allows the same degree of pulse rate control as

ingressive vocal fry but does not appear to produce individual pitches or

pulses as loudly. Microphone amplification is usually necessary to

project both modes of vocal fry. An attempt to produce ingressive vocal fry very loudly

can result in dryness in the throat or

coughing.

Ingressive

vocal fry can produce very stable pitches, i.e., pitches which can be sustained with

little or no wavering, in the area of E 41 Hz to C# 69 Hz in both male and

female voices. Words are easily articulated in this range, as well as in higher

ranges, although many of the consonants must be performed egressively for greater clarity or to avoid a

lisping effect. As ingressive pitched vocal fry rises in pitch range, it

gradually resembles egressive singing,

especially above the area of middle C, where it seems to lose any resemblance to the click-like quality of the lower pitches or individual

pulses. This area can be

controlled in terms of pitch, duration, vibrato, and dynamics (although not as

reliably as a comparable egressive range) and is

particularly useful in producing very soft, high pitches (area above B 967 Hz).

Ingressive phonation in the range above middle C has greater practical value in producing more unusual sounds

such as complex multiphonics (see VI. Complex Multiphonics).

Pitched ingressive vocal fry in the area between approximately D 73 Hz and

middle C seems to be the least practical for individual pitch control or

other more specific uses, although speech in this range may acquire an unusual

timbre.

Ingressive

vocal fry (or low ingressive speech) is the mode of voice production used by

the narrator in The Owl and the Pussycat. Tape Example 11

(see III. Ululation) demonstrates the resultant voice quality and

illustrates the possibility of wide speech inflections. Later in

the piece, all the vocalists are required to speak a short phrase ingressively, the group as a whole covering a

wide pitch range from low to high (Tape Example 18).

Specific

low pitches are produced by ingressive vocal fry in long passages of the "Dies

irae" ("Day of wrath"

) section of Requiem. The buzzy quality

of the ingressive pitch B

61 Hz, combined with the characteristics of the other techniques, seemed to the

composer particularly appropriate to the

mood suggested by the text (Tape Example 19). The ingressive pitched vocal fry which doubles the lower note of

the octave chanted (see V. Chant) by another

vocalist is more reliable than the chant and insures that the low B will always

be present.

One

instance of ingressive vocal fry in John Celona's Micro-Macro

demonstrates an unusually accurate imitation of the taped

computer-generated sweep of harmonics on the pitch

Db 69 Hz. In accordance with the instructions to blend with and imitate the tape, the vocalist sustains the

same Db and reinforces harmonics in a wide ascending and descending sweep (Tape Example 20), creating a timbre

very similar to the taped pitch. A short excerpt from the "Libera animas"

(" Deliver the souls" ) section of Requiem

requires fast pitch and text

changes of low ingressive pitched vocal fry in the lowest voice to create an organ

pedal effect (Tape Example 21).

Loud, nonpitched vocal fry begins the "Rex tremendae majestatis" ("King of

fearful majesty" ) section of Requiem

(Tape Example 22). The unison rhythm of the taped voices is answered in

unison by the live voices, both at a fortissimo level made possible through

close-miked amplification. Immediately preceding this

section, a very different effect is created through a single voice producing a softer, slower

vocal fry against a background of sparse

whispers (Tape Example 23).

Very slow,

individually pulsed nonpitched vocal fry forms the

basis for text articulation in Roger Reynolds' Still (Tape Example 24).

Syllables and words are formed and gradually

perceived over long, fairly even pulse streams. The eerieness

of inflected but unvoiced, pulsating words is often increased by overlaid

whispers and by the air sounds between pulses of the vocalist's slowly indrawn breath. A

slightly different example of nonpitched,

individually pulsed vocal fry from the middle of David Evan Jones' Pastoral (Tape

Example 25) demonstrates an interplay of varying pulse speeds between live and taped voices.

Chant

The term " chant" refers to one technique of singing an

octave multiphonic, i.e., one voice

producing simultaneously two pitches one octave apart. Low-pitched chant (the lower pitch

in the area of B 61 Hz to D 73 Hz) resembles chant used in certain Tibetan Tantric Bhuddist schools. This Tibetan

chant sounds like a three-note chord because of a strong

reinforced harmonic above the octave multiphonic.

When chant is produced with higher pitches, the harmonic content is less noticeable

and the sound is thinner and buzzier. The vocalist's physical sensation of chant may be

described as a light singing tone combined

with vocal fry. The sung tone is the upper pitch of the octave, and the vocal fryseems to lock into place with it to produce the lower pitch.

This rather delicate process renders

the chant less reliable than other techniques; the least amount of phlegm may necessitate considerable clearing of the throat to

produce a clear, unbroken, resonant sound. In

some instances, a loud sung tone preceding a chanted octave seems to prepare

the vocalist in the same way that clearing the throat would remove a mucus

obstruction. One example of this occurs at

the end of Psalm of These Days II (Tape Example 26). The vocalist generally

has little or no trouble chanting a C (130 plus 65 Hz) after several seconds'

rest following a quadruple forte Bb 233 Hz. In this example the original

notation showed only a low C (65 Hz). The. vocalist could not produce this note in his normal singing range and chose chant as the technique which would

produce a C 65 Hz that would blend best with the other pitches. Chant is

used effectively by both men and women to produce pitches lower than those in

the normal singing range.

Chant seems

to require an extremely steady airflow to maintain a smooth, unwavering

tone. It is best produced with straight tone. The addition of vibrato, which alters

pitch and/or intensity, or ululations, which regularly interrupt the airflow,

might upset the delicate balance of whatever vocal adjustment produces the

chant. Fast pitch changes are less dependable than long or repeated notes

and may result in the loss of the lower

chanted pitch.

One or more

of the following suggestions may insure a reliable chant production at a

specific point in a composition. The chant may be: (1) prerecorded on tape; (2)

performed by several vocalists simultaneously; or (3) used in combination with

other techniques which would double the pitches of the chant. The

lower chanted pitch is usually the

first to disappear, leaving a weak or unsteady upper pitch.

The opening

of Requiem uses chant to highlight certain portions of the text. A solo voice

on prerecorded tape provides a reliable basis for the live soloist to double selected

words with chant. Refer to Tape Example 3, in which the soloist chants with the

tape on the words "Domine"

and "Deus in Sion," as well as the entire last

sentence (Tape Example 27).

The

"Dies irae" section of Requiem begins

with chant and pitched ingressive vocal fry

combined on tape (refer to Tape Example 19). The texture gradually thickens with additional

taped voices chanting on higher pitches (each F# and B up to B 493 Hz). Some chanted

pitches are doubled with egressive singing or

ingressive pitched vocal fry; the live voices use

either chant or vocal fry on the lowest pitches. Tape Example 28 provides a short excerpt from the most dense part of the section.

Nonpitched chant

combined with vocal fry and glottal whispers produces a quite different

total sound. These techniques are combined in both live and taped voices in Requiem (Tape

Example 29), using the words "dona eis

requiem. Amen" at the end of the " lacrymosa" section.

Low chant,

even when soft, is generally quite resonant and full. This may explain in

part why it can effectively produce a settled feeling or a cadential

sense of resting point or arrival. Isolated examples of this cadential quality appear at the end of Psalm of These

Days II on the last syllable of " forever"

(refer to Tape Example 26) and on the word "sleep"

in Pastoral (Tape Example 30). A more extended use of chant to produce the

sense of a strong final cadence appears in the continual overlapping

of live and taped voices chanting a

low B (123 plus 61 Hz) in the last section of Requiem (Tape Example 31).

Two

instances of chant in Psalm of These Days II illustrate a sudden shift

in several parameters when chant immediately follows normal sung tones

without vibrato. In both examples (Tape Example 32, 33) pitches become much

lower and dynamics much softer, and there is an obvious timbral

shift to a thinner, buzzier quality. Even though

three of the four voices in the first example drop only one pitch, the addition

of the lower octave suggests

a large intervallic leap. The pitch shift in the second example is much more extreme,

the distance in each voice covering two to three octaves. In both instances,

the sudden dynamic reduction is a function of

the chant technique, especially since only general rather than

individual microphone amplification is used.

Chant

functions as an ornament to the word "my" in Psalm of These Days

11 (Tape Example 34). In this

instance, the instructions for two of the four voices indicate "multi-phonic

chant on and off." Each voice sustains one pitch with several similar ornamental

figures of rapid pitch changes resembling a trill, the chant adding a lower

octave at random.

Complex

Multiphonics

The term

"complex multiphonics" rather loosely

designates a cluster of sounds produced egressively or ingressively by one voice. The cluster may be perceived as

a number of non-intervallically related pitches

resembling noise or as a complex mixture of vocal fry

with other sounds or pitches. The total mixture can cover a narrow or wide band of

sound at various general pitch levels (low, medium, high) as well as on and around

specific, perceivable pitches. Complex multiphonics vary greatly among individual vocalists

but are fairly consistent for each individual. Those which are most reliable

for the individual vocalist can generally be reproduced with

a similar degree of complexity at approximately

the same pitch levels.

The major

difference between complex egressive and ingressive multiphonics lies in the amount

of air used to produce them. The egressive version,

referred to as " forced blown" by EVTE, requires a large amount of air, is

usually fairly loud, and can be sustained for a short time only. Although it is possible to

produce complex ingressive multi-phonics with a large amount of air, this yields a gasping

sound and may lead to coughing or choking. However, if a very small amount of air is

gradually drawn in, very complex multiphonics can be

sustained for a much longer time (one long breath). The physical sensation is

similar to ingressive vocal fry. Both types of multiphonics

are best amplified with microphones to avoid undue strain on the vocalist in

an attempt to make them louder. Both ingressive and egressive

multiphonics tend to tire the voice more quickly than other techniques and

should be used carefully.

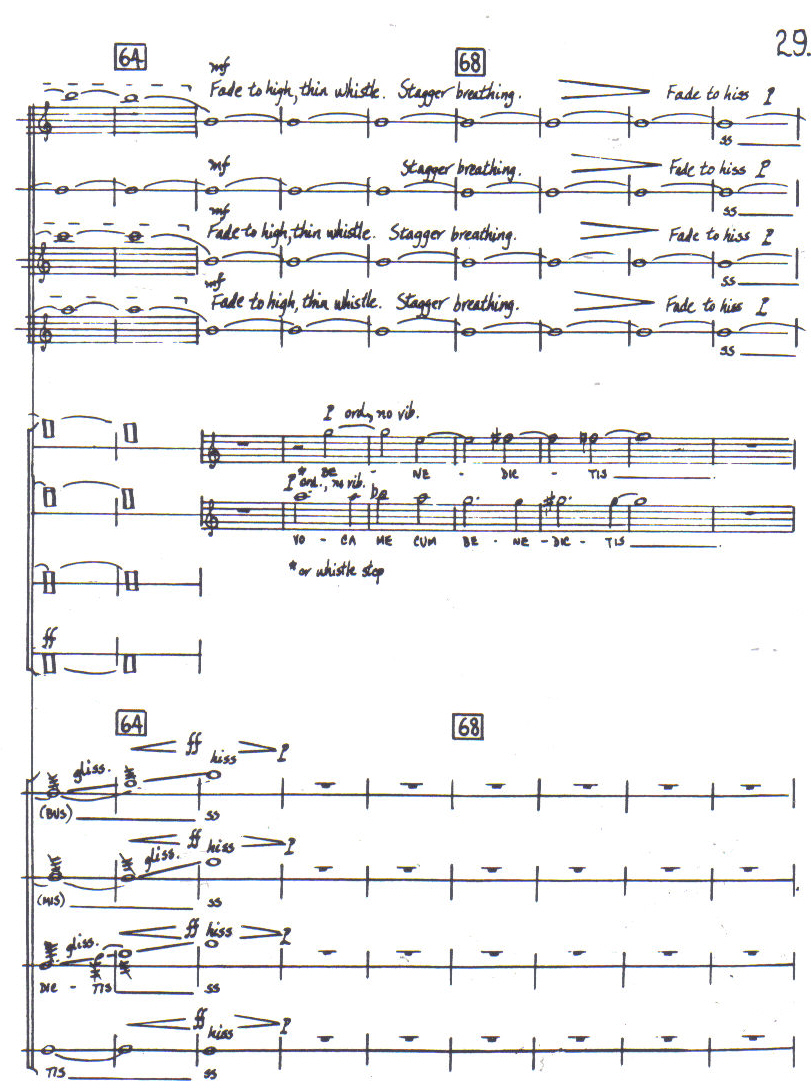

A short

burst of multiphonics supports the climax of a middle

section of Requiem at the words " confutatis

maledictis, flammis accribus addictis" (when

sentence is passed on the damned and all are sent to piercing flames" ).

The upper two of four taped voices hold a long, high ingressive multiphonic while the lower two have several repeated lower

egressive bursts

(refer to Tape Example 16). The combination of these multiphonics with high whistles, vocal

fry, and cross-register ululations creates a complex texture covering a wide, approximate

pitch range. In a much longer section in Still (Tape Example 35), the

illusion of a light wind gradually developing to hurricane proportions

is achieved through various combinations

of whistles, high ingressive pitches, and complex multiphonics.

Since complex multiphonics do not always "speak" immediately, it is wise to allow for some preparation. Several possible types of preparation may include: (1) using other loud or complex sounds to cover the entrance of the multiphonic; (2) instructing the vocalist with the most reliable multiphonic to enter first if several voices are to produce multiphonics; (3) preceding the multiphonic with a sound from which it is relatively easy to build the multiphonic. One example of the last suggestion occurs in Requiem in the "Rex tremendae majestatis" section (Tape Example 36). In both taped and live parts, vocal fry is followed by high, complex multiphonics. The physical sensation in producing both techniques is somewhat similar, and one seems to follow the other quite easily. The long sustained multiphonic on "salva me" near the end of the example is prepared by the shorter preceding multiphonics in the same voice and its entrance is covered by multiphonics in other voices.