Concerning

Orchestration in Webern's Konzert, Opus 241

David

Evan Jones

In what sense is Webern's Opus

24 a "concerto"?

It displays, to be sure, the traditional fast-slow-fast organization of the classical three movements, and

other (barely functional)

remnants of classical sonata forms. But texturally, few of the classical

devices remain. There are no highly

ornamented solo lines, no ostentatious technical virtuosity, no cadenzas. Indeed,

the drama of rivalry between soloist and orchestra is compressed and obscured to the point of putting in doubt

the entire question of who the soloist

is. Is the piano the solo instrument? Or does it serve the role of orchestra to

the eight-instrument(!) concertino? In this brief article, I will

explore some orchestrational and textural issues raised by Opus 24 and, in the

process, develop an alternative view of the

unique "rivalry" taking place in this piece.

It

would seem at first, that the Concerto form is in

itself antithetical to Webern's style and technique.

A "rivalry" requires the predominance, at various times, of one voice

or another, and yet the intensely

contrapuntal style of Webern's instrumental music maintains all voices as primary. Ornate and

ostentatious technical virtuosity are important elements of the traditional concerto form, but have

no place in Webern's concise sonic structures. How then, does Webern

express the central characteristics of the concerto form?

To

begin with, we must look at Webern's selection of

instruments. We observe:

1.

The piano is the only percussion instrument (and thus,

the only non-sustaining

instrument).

2

The piano is the only instrument designed to play

aggregates (the strings

excepted - and double stops are never

used in Opus 24).

3.

The instruments other than the piano are strongly

weighted towards the

high

end of the pitch spectrum.

4.

The

piano range encompasses the range of the other instruments.

Flute

Oboe

Clarinet

Horn

Trumpet

Trombone

Violin

Viola

Piano

Given

the above information, we can observe the following:

I.

Due

to its distinguishing attack/decay characteristics (in contrast to other instruments), the piano will naturally tend to

stand apart unless great care is

taken in writing to see that this does not occur. As Webern

does not disguise the piano attack

(quite the contrary), we can assume he wanted it to stand out. In

fact, Webern uses strong accents in the piano to

structure the rhythm of the first movement in particular.

II.

The ability of the piano to play aggregates is put sharply

in relief by the

fact that, while the writing for piano includes aggregates

of as many as

four pitches, the writing for the other instruments allows

more than two

instruments to sound simultaneously on only a few

structurally important

occasions.

III.

Because the ear tends to. gravitate

towards the higher sounds in a texture,

the higher

pitched instruments are traditionally the melodic instruments.

By

selecting an instrumentation (excluding the piano) weighted towards

the high

end of the pitch spectrum, Webern is opting for an

ensemble

which can compete effectively for the ear's attention. In

fact, solo instruments or concertinos are traditionally composed (usually)

of higher

pitched

instruments for this very reason.

IV.

On the basis of the differences between the attack/decay

characteristics of

the piano and the sustaining quality of the other

instruments, the ensemble falls into two parts: the piano and the remainder of

the ensemble.

Because the writing for the ensemble of sustaining

instruments is sparse and linear enough to be playable on piano, and because

the piano part is

at least as active as the total sustaining ensemble part,

these two "camps"

are

heard as the contending instrumental forces in the piece.

The above

observations mainly concern timbral quality, range,

and the capability of the instruments with regard to aggregates. But in Webern's technique, form evolves from the elements of a

piece, and the above observations have immediately observable structural ramifications as

well.

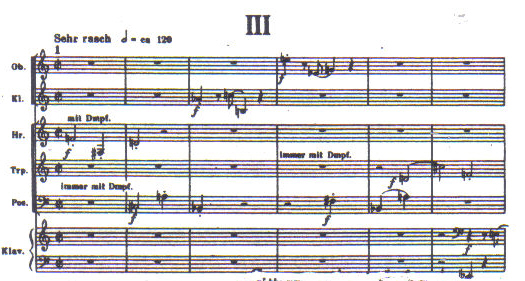

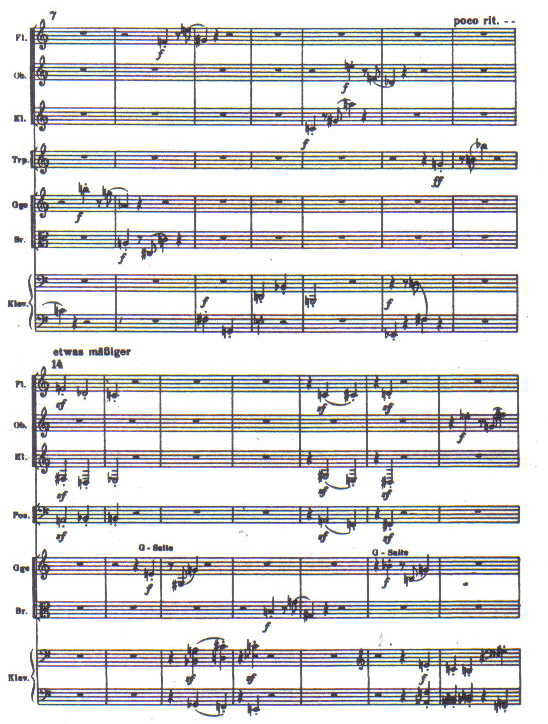

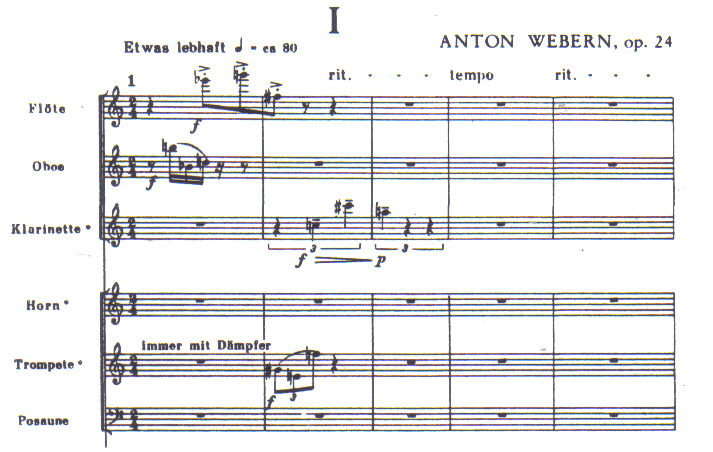

I.

Rhythm is

articulated mainly by the beginnings of notes, by attacks. The sharper the attack

of an instrument, the more definition its rhythms will have. In the first and third

movements of the Concerto, the piano 'sometimes uses this sharp definition to

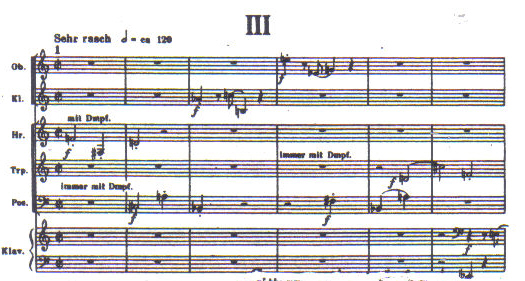

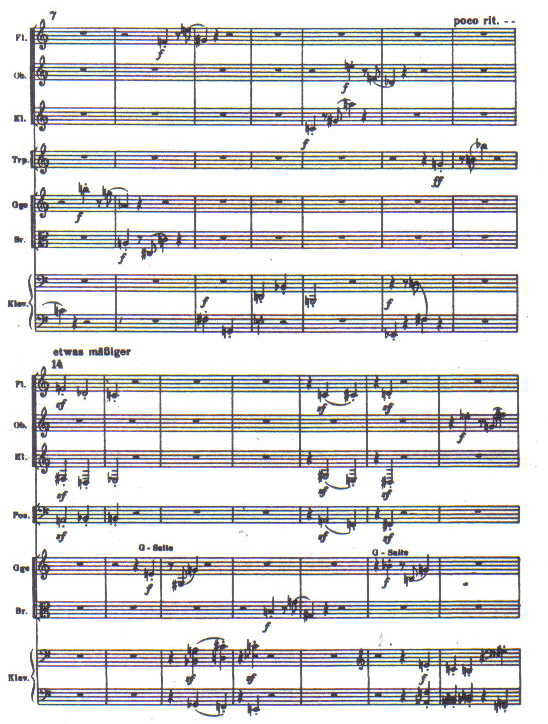

alter the perceived meter. The third movement, for

example, marches along clearly in two and with the

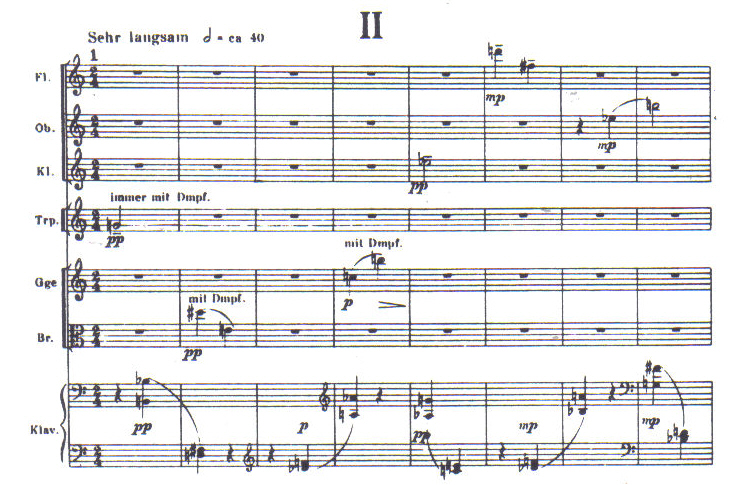

placement of the downbeat never in doubt until the piano in bar 16 (see

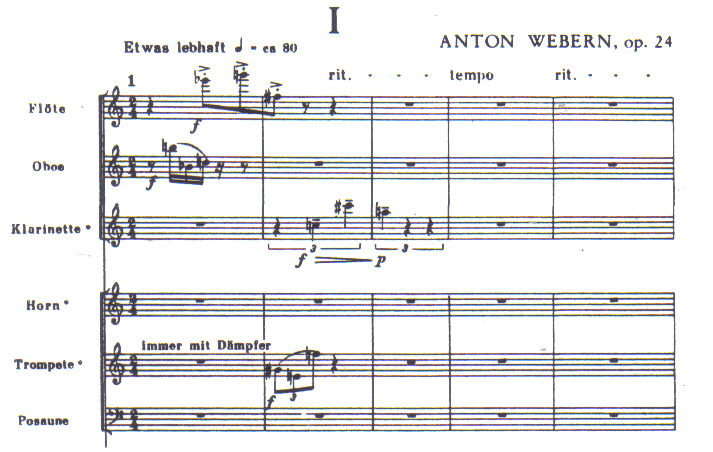

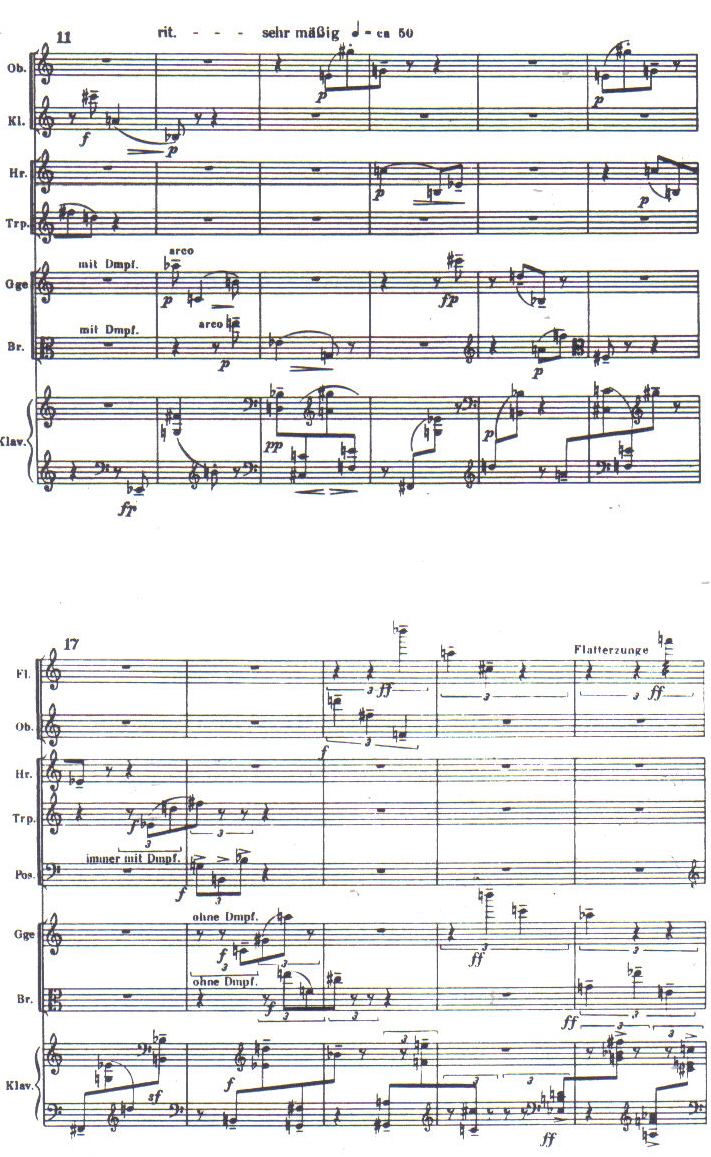

Example 1).

Example 1

Example 2

Neither the

trumpet syncopation in bar 13, nor the violin syncopation in bars 1516 altered

the perceived placement of downbeat for the following reasons. The trumpet B flat on

the second quarter of bar 13 ends the phrase, is followed by silence and then

by a reaffirmation of the notated downbeat by the winds (bar

14). The violin syncopation (bars 15-16) cannot affect the strong sense of meter

established by the winds because of its comparatively small impact or weight as compared with

the low wind aggregates. When the piano

enters with a low-midrange on the second

beat of bar 16, however, the perceived placement of the downbeat moves. The new

perceived downbeat is on the

second quarter of notated meter beginning with the piano sforzando

in bar 16.

This occurs for the following reasons:

1.

The motive the piano plays, in which three aggregates are

spaced by

half-note durations has always been played unambiguously on the beat

up to this point in the

movement.

2.

The

piano aggregates also gain authority from the

weight

of

the piano

played sforzando

in the mid-low range.

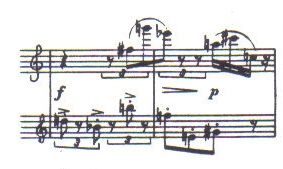

3.

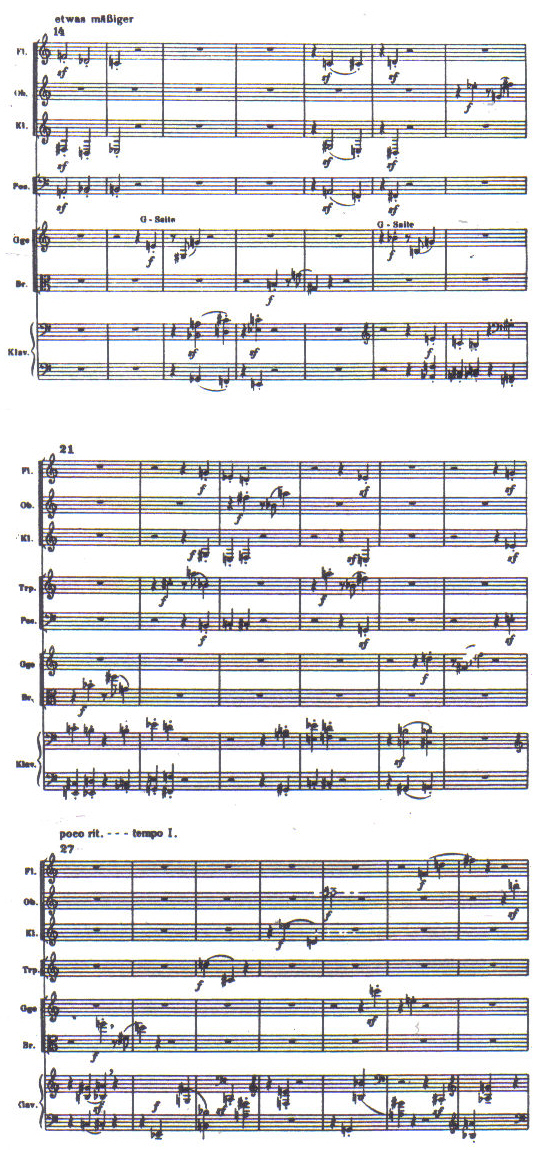

The new perceived placement of the downbeat is reaffirmed

(or at least,

not contradicted) by the material which follows up to bar

28 where the

piano changes the duple meter briefly but convincingly to

a triple meter

after which the perceived meter changes become quite

complex (see

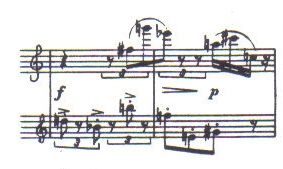

Example 2)

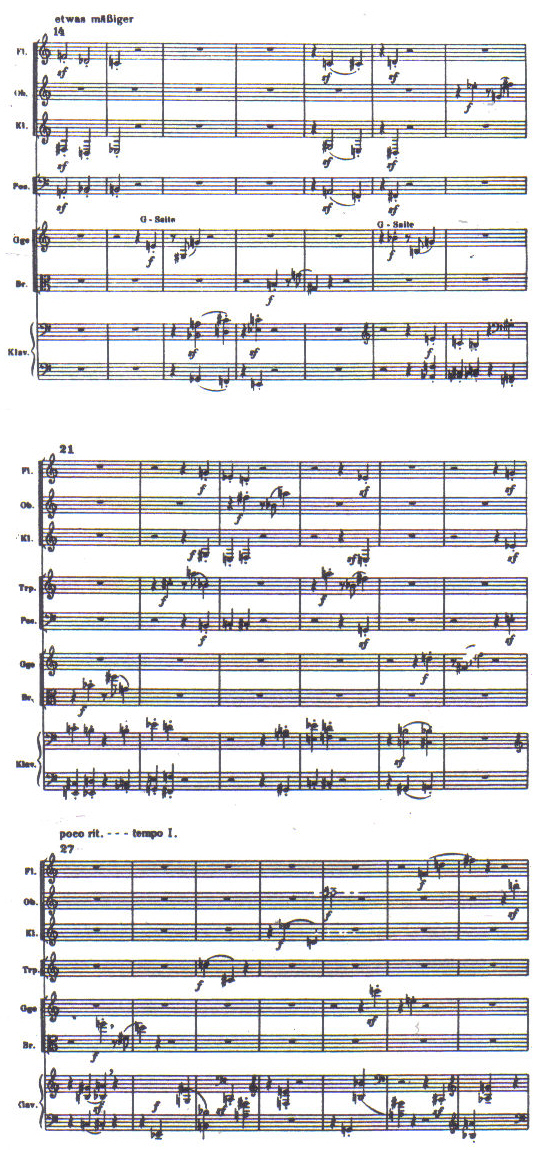

One

role the piano often assumes, therefore, is to alter or disrupt the perceived

meter. Placement of the audible downbeat - influence over the perceived

rhythmic structure -

these are areas in which the piano and the sustaining ensemble contend, and one in which the piano usually

dominates.

II.

The

percussive, rhythmic authority of the piano, and its

ability to play aggregates or

polyphonies is purchased at the price of control over the sustained dynamics of

the tone. As a

result, Webern assigns the dominant responsibility

for the development of line (the horizontal dimension) to the sustaining ensemble

(hereafter called " ensemble"). In this regard, the piano and ensemble are assigned two

opposing functions in the development of the

pitch structure.

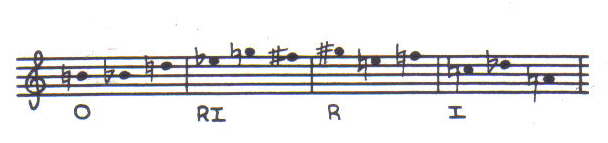

Before

deciding that his Opus 24 was to be a concerto, Webern

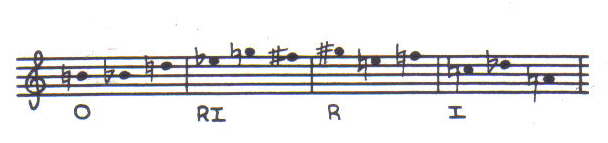

had developed the row he

intended to use for this piece. It is a "palindromic"

row which is organized in segments of three:

Example

3

The ways in which this row is

distributed among the instruments leads me to believe that the piano and the sustaining instruments represent two

different concepts of how the row is heard.

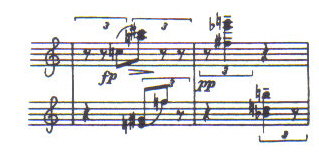

Consider the following:

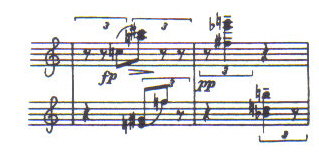

1.

A sustaining instrument rarely plays more than a single

three-note

motive at a time. Often they play only two notes and

sometimes a single

note. These short segments are generally hocketed together to form

longer lines (see Example 4)

2.

Only on the last note of the first movement and in the second

section of the third movement do the sustaining instruments appear in aggregates

containing more than two notes. Rhythmic unisons between two sustaining instruments generally occur as points of overlap between

succeeding segments. The orchestration of the sustaining

instruments is

thus

designed as a linear articulation of row segments which are

integrated rhythmically (by the points of overlap) but

not timbrally into

a larger line. That is, the timbres of the individual

instruments (and

often the

differences in assigned register) give each segment an independent aural identity while the rhythmic concatenation of

segments

identifies them

with a larger whole. Inversely, this larger whole can be

described as a single linear strand which is

"analyzed" timbrally and

registrally.

Example 4

The

piano, on the other hand, plays an integrative function:

1. The writing for piano varies from a

purely linear concept directly analogous to

the

writing for the sustaining instruments (see Example

5)

Example 5

Example 6

The

fact that the piano, as opposed to the ensemble is unified...

-

timbrally,

-

spatially (it is in

one location rather than several),

-

"cognitively"

( it is played by one player with accuracy which is

impossible

for several players playing together),

-

causes similar material played first by the ensemble and then

by the piano (as in bars 1-5)

to

sound much more

integrated on the piano - like a mapping of spatially diverse elements onto a single plane.

2)

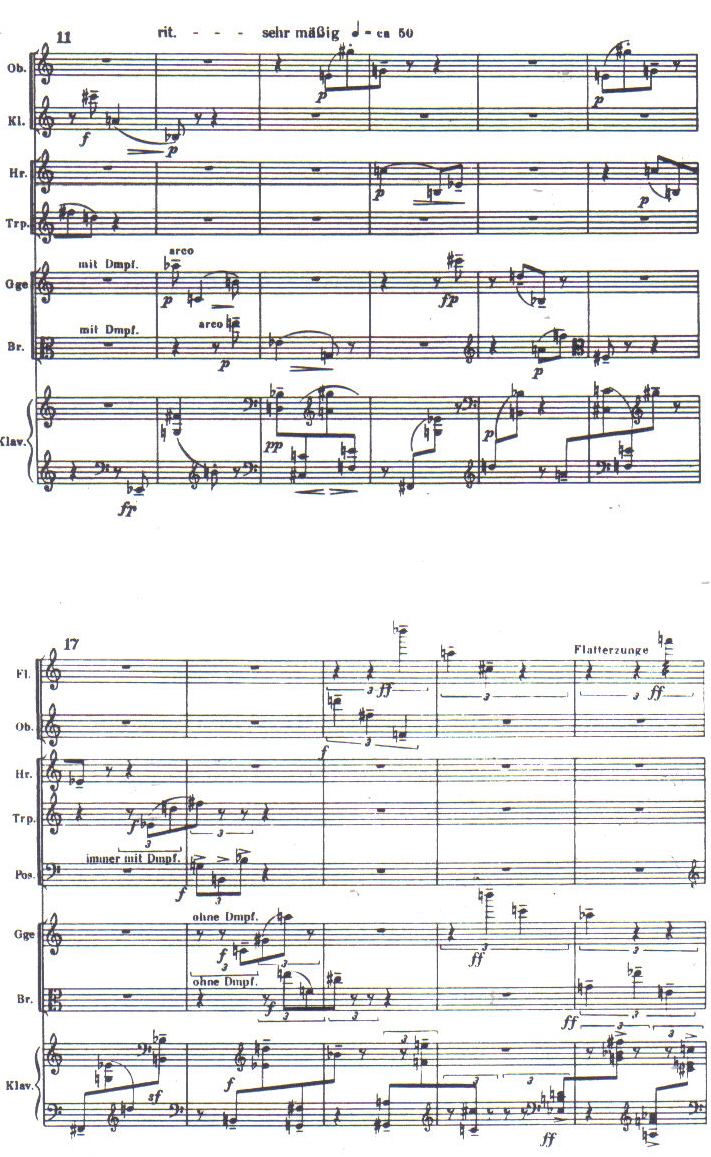

The piano serves an integrative function in another way as well: it is the piano which is mainly responsible for the harmonic or

vertical dimension. This is true not only of solo passages such as bars 9 and 10 quoted above, but more

generally, of passages .in

which the piano and instruments play simultaneously. The following passage is

typical of much more of

the texture of the first movement (aee Example 7).

Thus the piano "

integrates" in

the literal sense of telescoping the pitches of a segment together in a single articulative

gesture.

Example 7

In

passages such as the above it is the ensemble which tends to predominate. The piano, however, asserts itself with occasional sforzandi such as in bar 17 - often to mark a change of the perceived pulse or to alter the sense of

downbeat placement. The piano continues to play in counterpoint to the ensemble throughout most of the

movement and to provide an integrated

counterpart to the hocketed ensemble line.

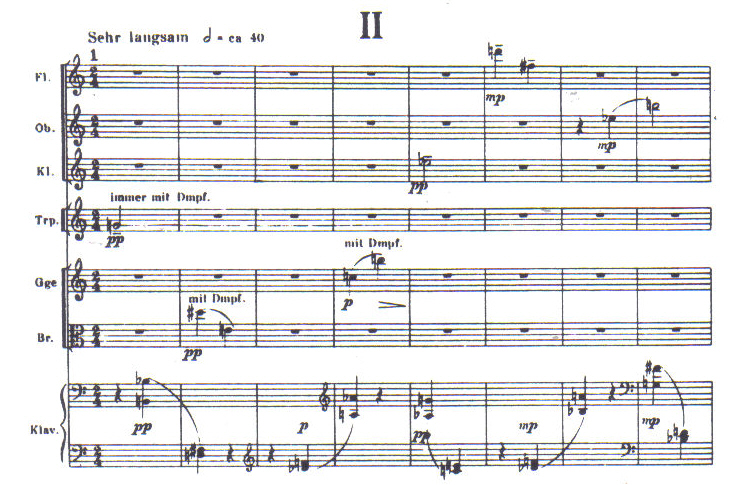

Webern's choice of an ensemble weighted towards the high end suggests that he did not envision an "accompanying" role for

these instruments. The consistent figure-toground relationship between the sustaining instruments and the

piano in the second movement,

lead me to hear the ensemble as a single multi-timbral

solo instrument supported by the

piano "orchestra" in this movement, and to some extent in the other

movements as well (see Example

8)

Example 8

.

The "palindromic"

nature of the row for this piece was inspired by a Latin palindrome

which fascinated Webern;

SATOR

AREPO

TENET

OPERA

ROTAS

Figure

1

In order for a palindrome to be fully

understood, one must examine each of its dimensions separately. One must read downwards and upwards, forward

and backwards in order to arrive at an

appreciation of the palindrome as a whole.

The relationships between piano and ensemble correspond roughly to the relationships between the means by which one learns to appreciate

a palindrome: The ensemble line

tends to analyze itself by its diversity of timbres so that we are aware of the

Inversional relationships between the "words" of which the

palindrome is composed. The piano line tends to integrate these "words" for us so that we can

hear the "palindrome's as a

reflective of a more fundamental complementarity.

Within this

closely defined complementarity there is no room for

"ornament" - in the sense of something non-essential. Every note played

is of structural importance. And because of this primacy of sonic structure,

there is no room in Webern's style for the writing of solo parts of

ostentatious difficulty.

The " virtuosity" of the nine soloists in this piece

is therefore of a very different order than in the traditional concerto. The difficulty of

their task lies precisely in the fact that their

parts are not ostentatious, but rather clearly and unadornedly

exposed. In the sense that the sustaining ensemble is a single multi-timbral "soloist" ,

their task requires a virtuosity of ensemble playing. This virtuosity is

required of the solo pianist as well, in addition

to which he must play with an unshakable accuracy and authority capable of fulfilling his role as a

counterbalance to the entire ensemble

,

The root of the word concerto is " concertare" - to fight

side by side," "to compete as

brothers-in-arms." This definition takes on new meanings in Webern's "Concerto, Opus 24."

1 The following

information is applicable to all musical examples in this paper: Copyright 1948

by Universal Edition, A.G., Vienna. Copyright renewed. All rights reserved. Used by permission

of European American Music Distributors Corporation, sole U.S. agent for

Universal Edition.

2 For

discussions of the pitch "magic squares" in the third movement (with nu 'million of orchestration), see,..

Cohen, David, "Anton Webern and the Magic Square", Perspectives

of New Music,

Vol. 13, pp. 213 215. Gauldlin, Robert, "The Magic Squares of the

Third Movement of Webern's Concerto Opus 24", lb

Theory Only, Vol. 2, 1977, pp. 32-42.