Pitch

and Texture Analysis of Ligetiís Lux

Aeterna

Jan Jarvlepp

Lux Aeterna (1966)

by Gyorgy Ligeti is a single movement composition of about

nine minutes duration for unaccompanied sixteen part mixed choir. There are four

soprano sections, four alto sections, four tenor sections and four bass sections. The piece may be sung by sixteen soloists

or by a larger choir divided into sixteen sections.

In this paper, I will discuss how the piece has been

composed from the point of view of horizontal pitch

lines and the resultant vertical textures. In doing this, the overall structure of the piece and the relationship

between music and words will become apparent.

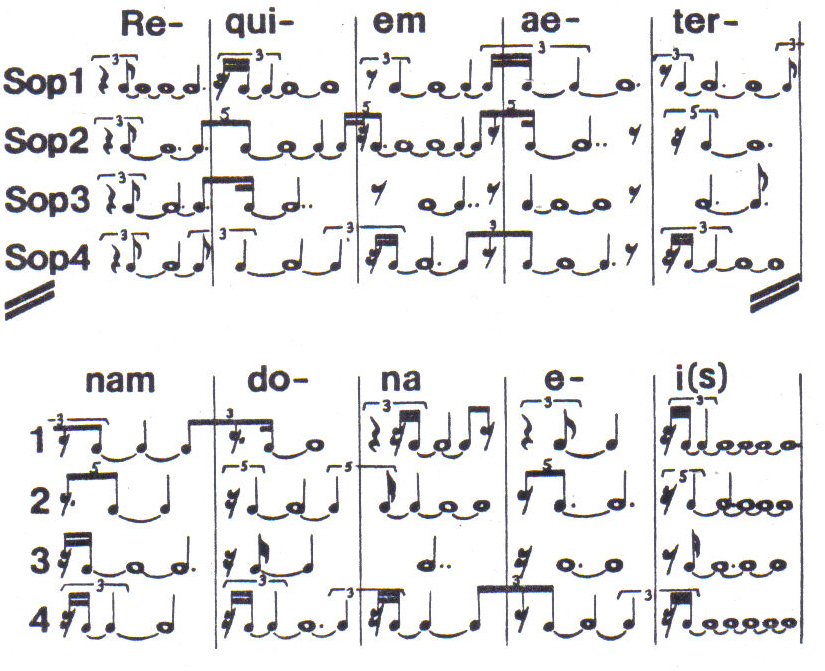

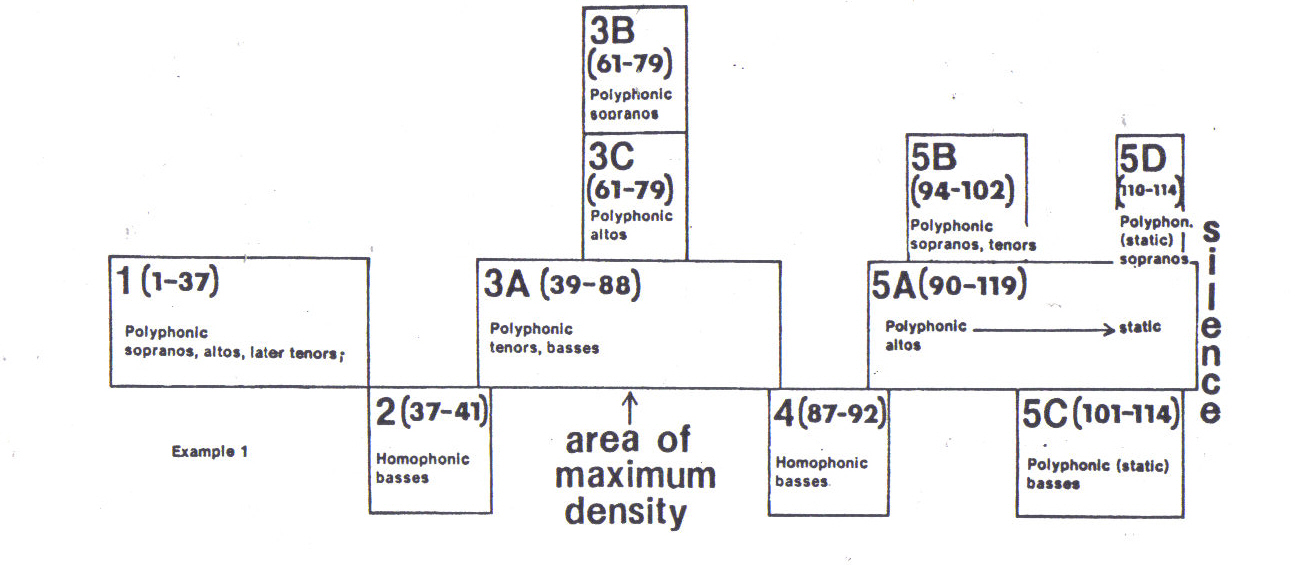

To give the reader an overview of the piece and to serve

as a point of departure, the blocks of texture

are presented in a graphic form in Example 1. The entire text

of the piece can be seen in Example 2. Notice that there are ten self-contained

textural blocks.

Example 1

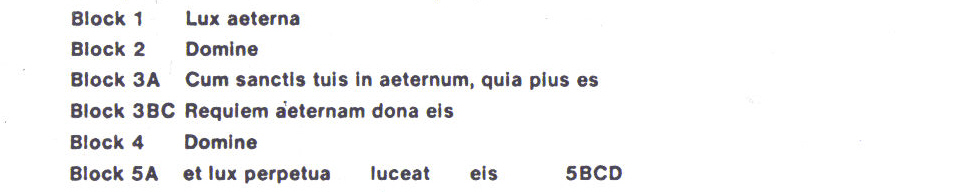

Example 2: The last line of the original text is a repetition of the text found in block 3A and has not been used in this composition

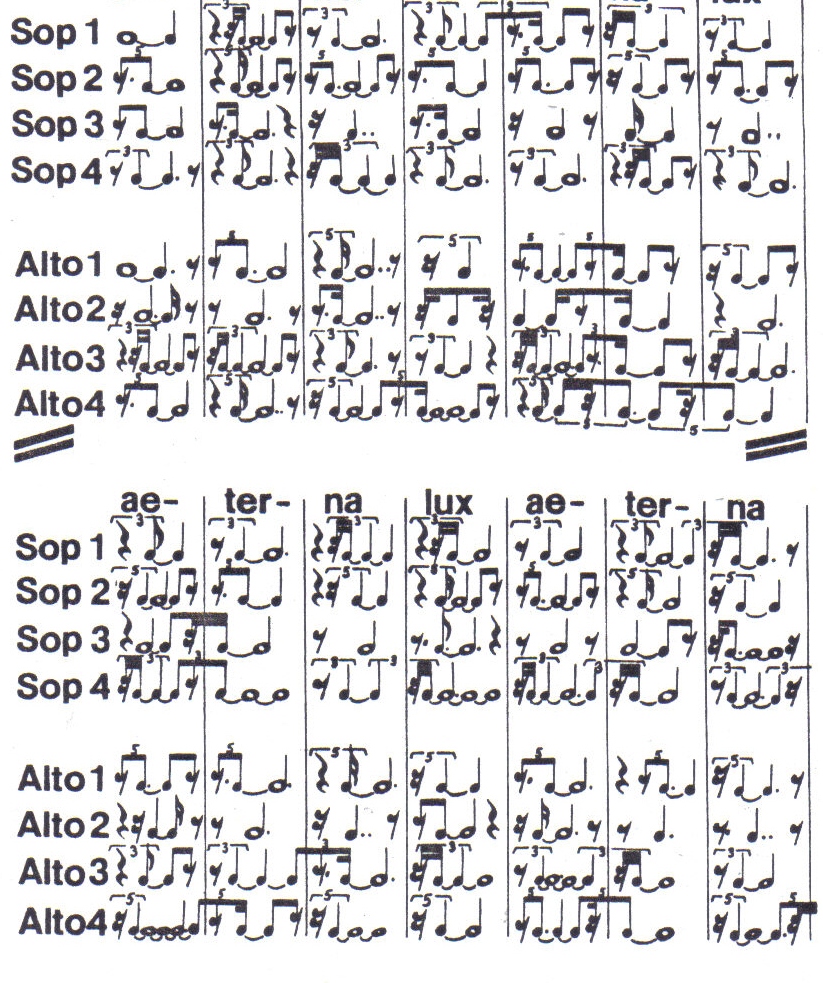

Two kinds of texture are used in this piece: homophonic and polyphonic. There are only two short instances of homophony which appear at structurally important places in the piece. The rest of the texture is strict imitative polyphony at the unison, which can be called canonic although one must abandon all ideas of tonal or modal resultant harmonies that are associated with traditional canons. The words of the text are also treated canonically. Each syllable appears with a particular pitch of the canonic melody, except in block 3C which uses an exceptionally short canon to represent a large number of syllables. Canonic representation of the words generally causes them to be unintelligible, while the word sung in the homophonic sections is clearly intelligible. Textures appear in blocks, either alone or in layers.

For clarity, I have named blocks that are superimposed on a previously established textural layer with the same numeral but a different accompanying letter (for example blocks 3B and 3C are superimposed over the previously established block 3A). Note that the three most important structural blocks of the piece are 1, 3A and 5A. Blocks 3B and 3C are fully temporally enclosed by block 3A, and blocks 5B, 5C, and 5D are temporally enclosed by block 5k.

These three

important structural blocks are separated from each other by the two occurrences of homophony which make up blocks 2 and 4.

While the

homophonic sections start and stop simultaneously, the polyphonic sections have two ways of starting and

stopping. They can start additively,

that is to say that voices enter one at a time until all have entered creating a canonic texture. They can

also enter simultaneously on the same pitch and then continue with the rest of the melodic line in staggered

fashion, thus creating a canonic internal texture

following a simultaneous attack.

Similarly

there are two ways in which the polyphonic blocks can end. One is a subtractive ending in which the

voices drop out one at a time as they finish their canonic material. The other is a simultaneous

ending which occurs after all

the singers in that block have reached the last note of their melodic line. This means that the first singer to

arrive at the last note will sustain that note until

all the other voices have also reached that point.

Before

examining the textural blocks individually, note that the piece never exceeds the 'p' dynamic level and

that the only dynamic levels specified are ppp, pp and p. (There is an alto If' marking in the low

register that the composer

says should sound as loud as a tenor or soprano 'p'. Therefore it is

heard as a 'p'

level.) There are no accents, crescendos or decrescendos, but many end with a

`morendo' indication. All entries are marked "enter very gently" or "enter imperceptibly" except

block 2 which enters "quasi eco". These gentle entries help create a smooth texture.

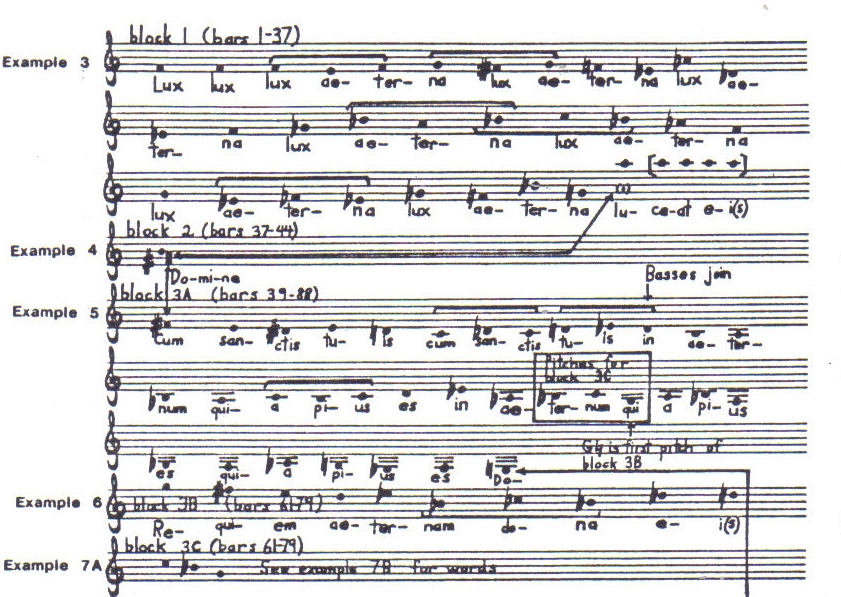

Block 1

(bars 1-37) is an additive canonic texture built entirely from temporally delayed superimpositions of

the line found in Example 3. It is constructed using strict pitch imitation as well as word imitation. The

words "lux aeterna

luceat eis" mean "may eternal light shine on them." There may be

some wordpainting of the

word "lux", which means light." We tend to think of both light and high pitches as being

brilliant; Ligeti assigns the highest pitch of bars 1-11 to "lux" (A flat). He also

assigns the highest pitch in bars 12-23 to "lux",

(a C).

The words

"luceat eis" do not appear until bars 24-37 where their presence is structurally reinforced

melodically. These words are sung on a high sustained A, which contrasts with the preceding

melodically moving setting of the words "lux aeterna". The ending of this textural block is

a simultaneous cut-off

with no "morendo" indication. One voice actually sustains the pitch after the cut-off to connect to the

next block, but is not discretely perceived by the listener. Note that the letter `s' of the word

"eis" is not to be pronounced by the singers, presumably to avoid the introduction

of sibilant sounds into a pitched texture.

The melodic

line of block 1 consists of a gradual intervallic expansion from the starting

pitch F, to a major 7th range (D flat to C), and an ending on the sustained high A. The polyphonic result is

a single tonic note, F, which expands into a dense harmony without prominent pitches, for example bar 13, and

then gradually moves to the

new central pitch, A, starting at bar 24. In bars 23 and 24, the harmonic texture is very thick

and the original F central pitch is absent. One can see

and hear that the harmonic mass is moving away from F.

The A pitch

first appears in bar 13 in a dense cluster at which point it is in its lower octave and not individually

perceptible. Similarly, the previously important F is no longer individually perceptible. The A

gains great prominence in bars

24-37 by appearing an octave higher while being supported by the original A-440 pitch. It is the highest pitch

heard yet and very clearly the most important one at this point. (Since not all four voices

of block 1 get to sing the last four syllables on the high A due to the simultaneous cut-off, they are

enclosed in square brackets in Example

3.)

There are

several occurrences of neighbor motion found in the melodic line. They are marked in the examples

with horizontal brackets. Whether this is coincidental or a deliberate compositional device

is not known. However, they appear later in other

polyphonic sections and act as unifying cells.

Block 1 is

written entirely at the 'pp' dynamic level, yet one perceives dynamic changes. These are due to the

gradual addition of voices, expansion of pitch range and especially the addition of the high A to the

otherwise midrange texture.

The density of pitch classes range from a minimum of one in bars 1-3 and 36-37, to a maximum eight in bars 22-24.

Block 2 (bars 37 - 41) is a sudden contrast to block 1. Three bass sections sing at the 'pp' level compared to twelve sections singing at the `pp' level in a high register before. We hear the bass singers for the first time, a timbral contrast, and we hear homophony for the first time, a textural contrast. The notes are sung in falsetto providing a further timbral contrast.

As

mentioned before, this homophonic section separates two large polyphonic sections and is therefore

structurally very important. This is the first setting of the new word "Domine" which

means "0, Lord". It has the function of breaking up the text in the same manner as it

separates blocks of polyphonic writing. There appears to be some subtle wordpainting here. The three

bass sections can be

considered a representation of the Holy Trinity. The male voices, which contrast with the

predominantly female texture before, indicate God, who is male as Christ. The

static harmony can be considered to portray God's never changing presence while the lower

dynamic level indicates the peacefulness

associated with God. Falsetto voices indicate that God is high (in Heaven).

This block

is composed of the pitches F#, A and B above middle C (see

Example

4). This combination of pitches sounds like a B 7th chord in which

the B replaces the

preceding A as the predominant pitch. However, the same A becomes the middle

note of the bass chord thus giving a pivot note or pitch connection to this

block. The highest note of this block, B, is not present in block 1. lt seems that Ligeti has been

saving it for this structurally important entry. The initial F of the piece is not present,

confirming the motion away from the original central

pitch of the piece.

Block 3A

(bars 39-88) enters with a unison F# in the tenors and overlaps with block 2, which fades out. The F#

is taken from the bottom note of the bass chord in block 2 creating a pitch connection. F#

becomes a temporary central pitch

but within two bars it becomes part of a cluster without any prominent pitch. Block 3A is a strict pitch and

word cannon in which all four tenor voices start simultaneously and then are

staggered creating imitative polyphony. It is derived completely from the melodic line shown in Example

5. Note that the neighbor motion cells found

in block 1 are also present in this line.

A new line

of words is being set: "Cum Sanctis tuis in aeternum, quia Pius es" which means "with thy

saints forever, for thou art merciful." The 'pp' dynamic level of block 1 is restored, thus giving

block 2, which separates them, further autonomy.

Tenors begin this

texture and are joined by the basses once the

texture is well established. The simultaneous entry of the basses, at bar 46, on a

unison D

is misleading since it sounds like the

entry of

a new textural block. However,

this D comes from the tenor line. The basses then proceed

to canonically imitate the tenor line starting with the

word "in" on D natural (see Example 5). After

the basses have joined the texture, the harmony becomes very neutralized (i.e. without prominent pitches). About ten bars later an A flat pitch

center begins to appear. (Note the strength and exact location of pitch centers varies

from performance

to pertormance since different singers project important pitches with varying degrees of loudness. For this reason, I cannot

pinpoint the emergence

of a new pitch center to a specific bar in this case.)

The canon

in the basses catches up with itself at bar 61 on a simultaneously attacked G. Blocks 3B and 30 enter

here, causing the bass sections to sound as if they are also entering with new

material. However, the bass sections quickly become staggered again and continue to imitatively follow

the melodic line

established by the tenors. This technique uses the basses to underscore the entries of the sopranos and altos with blocks 3B and

3C.

Block 3A

lies below 3B and 30 in pitch range with no overlap. It is the longest single block, lasting 50 bars of the piece's 126 bar length.

In bars

61-79 the area of maximum vertical density of the whole piece is found. Here blocks 3B and 3C enter

simultaneously over the previously established block 3A. All 16 sections are singing and

by bar 64 the polyphony has arrived

at a totally neutralized cluster in which no pitch center can be found. The band of sound exceeds two octaves

and contains all twelve pitch classes. F and A, which were important pitch

centers in block 1, are present only below middle C. The composer has negated

his previously pitch-centered material in favor of a dense neutral texture with internal movement

but no apparent pitch goal.

In bars 75

to 79, the texture begins to thin out as blocks 3B and 3C leave the texture exposing some predominant

pitches in block 3A. F and E flat are heard as a bi-polar pitch center causing some confusion as to which is

the main pitch. In bars

80-88, this confusion is resolved with the appearance of Es above and below middle C, and the

disappearance of the F and E flat. The composer has prepared the entry of the octave Es by

presenting its inner adjacent pitches as a minor 7th harmonic interval. This creates a smooth pitch

transfer from an unclear adjacent pitch area to a

clearly defined pitch center.

In bars 80-88, the composer presents an interesting preparation for the next section, block 4. The syllable "Do" is sung on E preparing the word "Domine", which includes an E in its pitch material. The reason why this is coherent with the preceding material is that "Do" sounds like the first syllable of "dona", which was part of the text of blocks 3B and 3C. It is only by seeing the capital D in the score that one can tell the difference between the two.

The ending

of block 3A is a subtractive ending with the basses leaving the texture first in order to be able to re-enter at block 4. Block 3B (bars 61-79) consists of a canonic

representation by the sopranos of the

line found in Example 6. The words "Requiem aeternam

dona eis" mean "eternal rest

give to them". This block begins with a unison G attack, which is a

clearly audible entry, and then changes into polyphony as the voices canonically leave the initial pitch one by one.

Block 3B employs a subtractive ending in which the singers arrive at a final D

at different times and then fade out

one by one in accordance to the "morendo" indication. Block 3B is

linked to 3A and 3C by the common G.

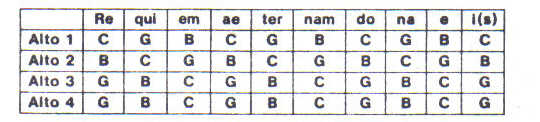

Block 3C (bars 61-79) appears simultaneously with block 3B, using the same text, but is different in pitch content and canonic structure. A repeating three note cell, C-G-B flat, is used to set a ten syllable line of text (see Example 7a). Another contrast with other polyphonic sections of this piece is that this block begins simultaneously with the same syllable sung with three pitches instead of one.

Alto 'I sings C-G-B flat repeatedly, Alto 2 sings B flat-C-G repeatedly and Altos 3 and 4 sing G-B flat-C repeatedly. (See Example 7B). The sequence of pitches never changes in this block. This three note pitch material can be found in the same order in Bass 4, bars 52-61, and later in all the other voices of block 3A as they arrive to these 3 pitches.

Example 7b: Block 3C, Altos (bars 61-79)

Block 3C

ends at bar 79 with a simultaneous fadeout on the syllable "i(s)". At the same time, block 3B is fading out

using the same syllable but the subtractive method of

ending.

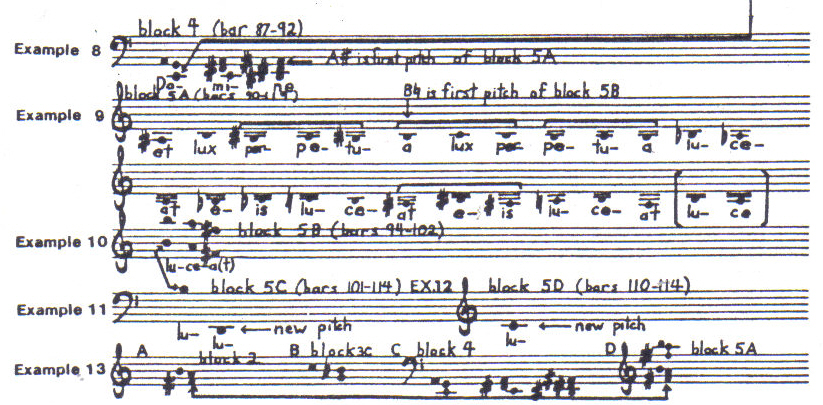

The second

instance of homophony, block 4 (bars 87-92), sets the word "Domine" as did the previous

homophonic section, block 2. As before, a three note chord with the same intervals is used. This

time the chord appears in the lowest bass register, which is a contrast to the falsetto setting of the

same word before. A 'pp' dynamic level is indicated

compared to the `ppp' of block 2.

Block 4 is

linked to block 3A by the pitch E, which is the last pitch of block 3A and the lowest of the three pitches

which begin block 4. The three pitches of the first chord of block 4 sound like an A 7th

chord. The A is the most

predominant pitch. The approach from E to A sounds like a dominant to tonic †motion. The two blocks are also connected by an overlap of 5 1/2 beats.

Unlike block 2, there is harmonic motion in block 4

(see Example 8). The second of the three

chords is an inversion

of the first, lowering the middle pitch by a semitone and leaving the outer

pitches the same. The third chord is an intervallic expansion of the second in which the two outer pitches each expand from the middle by a semitone. The second and third chords have their middle pitches in common.

While the notes of these chords look equivalent in the score, they tend to be perceived differently judging from the recorded performances that I have heard. The upper tone predominates while the lower two pitches add timbral richness whose pitch content is not as evident. Therefore, when the upper pitch rises by a semitone to the third chord, it causes us to perceive that the general pitch level is rising by a semitone, even though the lowest pitch drops a semitone forming a D# minor triad. The attack of block 5 coincides with the beginning of the third chord of block 4. This creates an overlap between the two sections as well as a pitch connection since the first note of block 5A is an kg an octave above the highest pitch of block 4. it also reinforces the semitone rise in block 4.

Block 5A (bars 90-119) sets the words "et lux perpetua luceat ei(s)- meaning "and let perpetual light shine --be set since the composer omits the last line of the original† presumably to because it has already been set in block 3A and would be an unnecessary repetition.

The melodic line, from which block 5A is built, can be seen in Example 9. This block begins with a simultaneous attack on A# by the four alto sections, which then continue the melodic line in canonic fashion

The three note neighbor motion cells, which are present

in blocks 1, 3A and 3B are also present here and are

marked by horizontal brackets in Examle 9. The altos sing in their

lowest register throughout block 5. This gives a p relaxed quality to the setting of the text,

especially at the end. The rate rate of change from syllable to syllable is relatively fast at the beginning of block 5A

and gradually slows down to a

static interval in bars 114-119. The piece ends with the altos singing soft sustained F and G pitches below middle C.

They fade with out simultaneously.

This ending represents a return to the original central

pitch, F. This time it is accompanied by a G

above, possibly because the composer considers a simple return to the F

to be too simple, predictable or reminiscent of tonal music.

The final F of the piece is an octave below the first F of the piece representing a loss of energy and a greater sense

of relaxation.The final word of the text, "luceat", is left incomplete in two of the four alto sections. This

may word-painting representing the composer's interpretation of the text.

Block 5B (bars 94-102) starts with the sopranos and tenors simultaneously attacking B an octave apart. This line moves in very slow canonic fashion leading to a texture containing B, A and F#, which sounds like a B 7th chord (see Example 10).

The word being sung is "luceat" which means "let shine". It is taken from the text of block 5A. Here, 5B has the function of highlighting that particular word from block 5A. The B pitch is also derived from 5A, (altos 1 and 2, bar 94).

The B of block 5B is the highest pitch in the

piece as well as a moment of high tension. The high and bright sounding B may be a word-painting of

the word "luceat".

The tension of this high pitch is enhanced by the

use of the "hole in the middle"

effect. There is a pitch gap between the B, A and F# of block 5B and the underlying block 5A, whose pitches

do not rise above middle C. This effect has been used in orchestration by modern composers

as a tension building device.

One feels less at ease when harmonic textures contain large gaps in the middle. This effect is further

enhanced by the fact that the sopranos predominate over the tenors who are not

individually perceived. This makes the effective gap over an octave wide and

provides contrast to the more closed textures heard

before.

Sopranos 1 and 2, and Tenors 1 and 2 sing only the

syllable "Iu". This creates a coherent link to the opening word of the piece since the

listener cannot tell

whether the word "lux" or "luceat" is being sung.

The letter 't' of "luceat"

is not pronounced, presumably to avoid the introduction of percussive consonants into a smooth pitched texture.

Block 5B ends with a simultaneous fadeout which overlaps with block 5C. †s transferred horn block 5B to block 5C where the word is not completed. The high B is also transferred to the upper two voices of block 50 who sing the same pitch two octaves lower. A release of tension has been accomplished since the B is now in a more relaxed middle range and since the "hole in the middle" effect is now absent.

Block 5C (bars 101-114) is a static interval with an

additive entry and subtractive ending (see Example

11). In blocks 5A and Se there has been a gradual slowing down of the rate of pitch change. Ub blocks5A and 5B there has been a further slowing down of the rate at pitch change in block 5B.

This block cannot be considered homophonic

because of the staggered entry and ending. One does not aurally identify it with the homophonic blocks 2 and 4. It

tends to blend partially with the other blocks present and to act as a

soft drone.

The entry of the low D is a noticeable

event since this is a new pitch appearing in the unused low register of the basses. A small amount of

the "hole in the middle" effect is present but does not function in

the same way as before. Human perception is such that one accepts large gaps in

the lower register with little

experience of tension. For this reason it is possible in classical scores for string basses to frequently double the

cello lines at the lower octave, while an upper octave doubling of the first

violin line is an unusual special effect rather than a

normal mode of orchestration.

Since the total texture at this point

is not very thick, one starts to hear the sustained B and D as important central pitches.

There is confusion as to which pitch is the more important of the two. This is similar to the situation

found in block 3A at bars 77-80, where one's attention is pulled between F and

E flat, and the situation

in block 5A, at bars 115-119, where F and G compete for the listener's attention. It turns out that

neither is a central pitch but function as pitches

which precede the final F and G of the piece.

Block 5C overlaps with block 5D and ends

in an unusual way. Bass 1 joins block 5D and therefore leaves the pitch material of block 50. Bass 2,

which is the only section

left with B, fades out independently from the others. Basses 3 and 4, who have the low D, fade out

simultaneously. This type of staggered ending cannot be considered homophonic in spite of

the preceding sustained material.

Block 5D (bars 110-114) consists only of middle C held continuously over five bars. It has a simultaneous entry of four soprano voices and one bass voice, which leaves block 5C. This is the only instance of a voice transferring from one block to another. It has the effect of weakening the B which it is leaving, and strengthening the C which is its new pitch.

This section ends subtractively with staggered

fadeouts. Only the syllable "lu"

from block 5's "luceat" is sung. Like blocks 5B and 5C, this serves to

emphasize

"luceat" as a key word, and creates a connection to the similar sounding "lux". Block 5D (Example

12) can be considered as the last stage of the decreasing rate of pitch change that has taken place in blocks 5A, 5B and

5C.

This is the only block which cannot be

individually perceived. The composer has instructed the singers to "enter imperceptibly" at

the 'app' dynamic level.

Yet it is an individual block whose pitch content and point of entry do not coincide with any of the others. The C

pitch creates a quasi-dominant fifth above the lower F

pitch in block 5A.

Once block 5D has ended, the low F and G of the

altos are the only pitches left

in the piece. They are sustained for three bars and then fade out simultaneously over two bars. The piece ends with

seven bars of silence which Ligeti says "depend on proportions of the durations of the parts of the

piece."1 This seems to be a purely theoretical consideration

since in a live performance the audience is likely to begin applauding after

the singers stop singing, thus ruining the durational proportions. On the Wergo and Deutsche Grammophon recordings not only is the 7 bar silence

omitted, but each recording appears last on the side of the disc. The listener will probably

conclude that the piece has ended

when the singing stops and lift the tone arm from the record. In the case of automatic turntables, this will happen automatically.

Four sections of the piece employ a vertical three

note intervallic cell (shown

in Examples 13A, B, C, and D) in addition to

the horizontal three note neighbor

motion cells found in blocks 1, 3A and 5A. Both types of three note cells add coherence to the different

sections of the piece even if they are not consciously

perceived. The first vertical cell appears in block 2 (Example

13A).

The cell consists of a minor third and a major

second. The pitches B, A and

F# cause it to sound like a B 7th chord with no third to indicate whether it is major or minor. This homophonic

presentation of the cell is the simplest of the four

occurrences.

The cell reappears in block 3C (see Example

13B) a semitone higher than in block 2. The three pitches appear

simultaneously and are the basis of three independent

canonic strata within the same textural block (see Example 7B). Unlike block 2, this appearance of the

cell is difficult to perceive as a unity since two

other blocks of texture are sounding simultaneously.

The cell appears in the lowest register of the choir in Nock 4 (see Example 13C) note chords. The first is intervallically identical of the chord in block 2 but appears two octaves and a major second lower. The second chord is an inversion of the first in which the outer two the same. The inner pitch drops a semitone in order to form the inverted chord. The third chord is an intervallic expansion of the three note cell and therefore is no longer identical. Each of the outer two pitches expand a semitone away from the central pitch.

The last occurrence of the three note cell is in block 5A (see ExampleHere the pitches of block 2 are used with an upper octave doubling. The pitches are presented in a slow additive canon in which the first pitch is never left. It is this cell which creates the "hole in the middle" effect over block 5A.

This composition does not follow tonal patterns of

traditional harmonic music even though there

are numerous pitch centers and quasi-dominant 7th chords.

One might consider the three note cell found in Example 138 to be the dominant

7th chord of the F starting pitch of the piece. However, the strong B, A and A# pitch centers found in the other vertical cells do not fit

conveniently into a traditional tonal plan. There exists the possibility

that Ligeti used C as a vague dominant function pitch and the B as a substitute dominant as one

would find

in a tritonal axis.

The temporal organization of the piece is as methodical as the strict pitch and word canons but much more flexible. As Ligeti says "a kind of talea structure, not a rigid one as in the isorhythmic motets, but a kind of 'elastic' talea"2 is used to order durational values. In Example 14, the first 14 syllables of the piece are lined up in vertical columns so that the rhythmic values assigned to each syllable can be compared from voice to voice. No two voices are the same but there is a general tendency for some syllables to be shorter and others to be longer. For example, the first syllable, "Lux", tends to be longer than the second syllable, which tends to be longer than the third.

† ![]()

Example 14

Since the elastic talea is not a strict organizational

method, there are exceptions to the general tendencies of durational

values. For example, in the fourth syllable, "ae", Alto 2's duration is only

an eighth note whereas Alto 4's duration

exceeds eight quarter note beats. A similar exceptional case can be found among the generally appears that Ligeti wrote the first three soprano and

alto voices of the

xanon adhering to his flexible talea without great deviation.

However, the fourth soprano and alto voices are rhythmically much more

tlexible at times, accommodating† the exigencies of the rest of the texture.

The flexible talea structure of block 3B (sopranos, bars 61-79) is shown in Example 15 using the same vertical column format as the preceding example. Unlike the beginning of the piece, this canonic block begins with a simultaneous attack in all four voices. It then becomes canonic because the duration of the first syllable, "Re", is different in each voice causing them to shift out of phase with each other. The block ends subtractively as each voice reaches the final syllable "i(s)" at a different time and then decrescendos after sustaining it for several beats.

Example 15

Since the strict pitch and word canons are rhythmically

set using flexible talea structures, it is hard to hear any canonic

structure. The absence of any clearly

articulated head motive contributes to this situation. The quarter note beat is often divided into 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6 parts

giving a total of 12 possible articulation

points in each beat. The different divisions of the beat are frequently used for pitch changes making it impossible for the

listener to pick

a steady beat from the music. Instead

of hearing a tempo or a beat, one hears a smooth and continuous texture with internal changes. This method of canonic

writing avoids the "treadmill

effect" of the traditional rhythmically strict canon and hides the

composer's technique of building textures from a single melodic line.

In conclusion, this composition has been very methodically created using ten clearly defined blocks with very strict internal pitch construction. Homophonic and polyphonic structures have been used in a way that gives unity as well as variety. Each line of the text has been set differently giving variety to an otherwise unified text. The canonic techniques of early music have been employed to weave a contemporary fabric.

1Personal

communication from Mr. Ligeti, Nov. 2, 1981.

2Ibid.

Examples 3 - 13

Bibliography

Ligeti, Gyorgy. Lux Aeterna. New

York: CF. Peters, 1968.