Compositional Techniques in Karel Husa’s Early Serial

Works Poème and Mosaïques

Craig Cummings

Karel Husa was born in 1921 in

My

main reasons for not returning when ordered to were artistic, not only

political. I would study for two to four years in

Some observers describe Husa’s early compositions, such as the orchestra

pieces Overture (1944), Sinfonietta (1944), and Three fresques

(1947) and two early string quartets (1943 and 1948) as neo-Classic or

neo-Romantic in style.[2] Eventually,

however, Husa turned to serial techniques for creating musical compositions, though

always with his own approach and musical end results. In an interview

conducted in August 1995 and then published in ex tempore in 1996,

Robert Rollin and Husa discuss much about the composer’s life and

career. Several questions about serialism, along with Husa’s responses,

are quoted below.

RR: When did serialism begin to influence

you? When did you begin to experiment with serial techniques, and which

composers at that time influenced you?

KH: It was already starting in

RR: Schoenberg was at this

time in the

KH: Yes, he was in the

RR: So, who took his place as

the most dynamic figure? Was Boulez already involved?

KH: Boulez was

known, and already I had heard his First Piano Sonata. It was

mostly the works that I studied; it was not people. Stockhausen I knew

also in

Based on these comments, one might expect that Husa

would have turned fairly rapidly to using serial compositional

techniques. His life circumstances in the early 1950s may have temporarily

prevented such experimentation. Husa married and had children, and he

permanently left behind his Czech homeland, moving in 1954 to the

The important first serial pieces

came a few years later. Rollin’s conversation with Husa provides

interesting background:

RR: Returning to the question of serialism and the

new, more chromatic style that you were working on, which would you say, the Poème

for Viola and Chamber Orchestra (1959) or the Mosaïques for Orchestra

(1961), was the more pivotal piece for you in terms of serialism and the future

of your music for later years?

KH: I would say the Mosaïques

was more striking in colors, because I experimented with orchestral colors

especially. I liked the Poème too, because it’s more austere in a

way; it’s a piece for which I have affection, but it has less colors, because

it’s only strings, viola, oboe, piano, and horn.

RR: It’s within a more narrow

coloristic band, but still a very lovely piece.

KH: It’s a twelve-tone piece, but it’s in a style,

if you wish, of Schoenberg’s twelve-tone approach. Mosaïques is

already more what also Boulez and Stockhausen speak about. It’s not only

the twelve notes, but the rhythm and the dynamics are serialized too . . .

RR: I heard you

conduct a performance of it at Cornell with the Buffalo Philharmonic when I was

a student, and I remember thinking that it had an affinity to Webern, more than

to Schoenberg, which makes sense because of the coloristic aspect - perhaps

because of klangfarben, the very delicate movement of melodic material

from one instrument to the other. So, perhaps in a formal sense, the Poème

was the place where you first introduced serialism, then further developed it

in Mosaïques. Were there chamber pieces around that time also, or

were these the pieces in particular? KH: That [sic]

would be the pieces; then later came the Third String Quartet (1968) which

also uses some twelve-tone techniques, but it is much more free already.[4]

Husa’s Poème,

completed in 1959, thus marks a departure from his earlier style into a more austere

approach characterized by greater dissonance and serial procedures; it is a

turning point in his compositional output. It is interesting that its

original title, as found on the cover sheet of its sketch file, was Abstract

Poem. Within two years, Husa had completed his second largely serial

work, Mosaïques (1961) for large orchestra. As the composer himself

states, these pieces together represent an important change in Husa’s style and

technique. Accordingly, these seminal compositions are the works examined

in this study.[5]

Poème

By 1959, Husa had fully

settled into his new life, becoming a

Poème is cast in

three brief movements without breaks. The first movement, slow and

rhapsodic, is labeled improvvisando. The misterioso second

movement moves at a faster tempo and is the longest movement. The final

movement, labeled dolce, returns to a slower tempo and more

improvisational style. The first and third movements begin with lengthy

solo viola melodies and the piece concludes with the solo viola fading away

into silence.

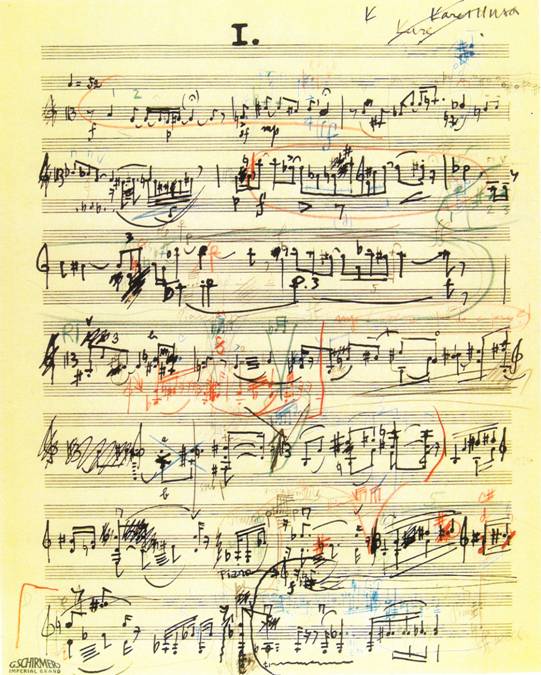

Husa’s sketches provide an

interesting opportunity to examine the serial logic of Poème. Thirty-five

separate sheets are included in the sketch file for Poème, located in

the Husa Archive at

While each movement has

its own row, there are strong connections among the three rows - so strong, in

fact, that Husa thinks of the piece as being based on a single row.[8] An

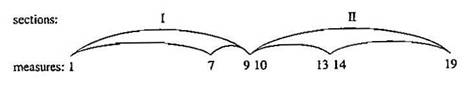

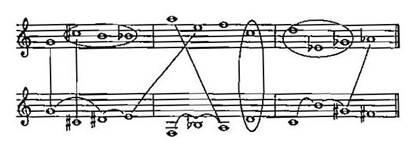

especially interesting sketch page shows Husa’s creation of a row consisting of

three tetrachords that he labeled A, B, and C (see Facsimile 1). He then

rearranged the tetrachords to create rows for the other two movements. The

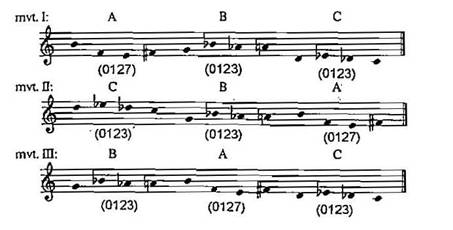

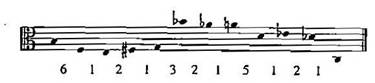

end result is shown in Example 1. Tetrachord A is a [0,1,2,7] pitch class

set, while tetrachords B and C are both [0,1,2,3] chromatic fragments, the

latter being a T5 transposition of the former. As is evident

from the example, the tetrachords labeled A, B, and C above the row for

Movement I are reordered into C, B, and A for Movement II and B, A, and C

for Movement III. Thus, each movement may be said to have its own

twelve-tone row, yet the underlying unity among the rows is obvious.

Example 1: Tone rows used in

Poème

Movement

I

Movement I is heard in two main sections: mm. 1 - 9

and 10 - 19. Section I begins with a dramatic solo

viola line, the orchestra’s first entry in m. 7 creating a strong subdivision

within the section. Section II also falls into two subsections: mm. 10 -

13 and 14 - 19. The first subsection is characterized by the viola

playing repeated, distinctive points of imitation in single

then double stops (see the first appearance in Example 2). The

orchestra accompanies with sustained pitches and suddenly reaches an apex

in terms of pitch density, registral expanse, and rhythmic complexity at the

beginning of the final subsection (m. 14). Interestingly, it is precisely

at this moment that the technical virtuosity in the solo viola abates. The second subsection moves directly into the second

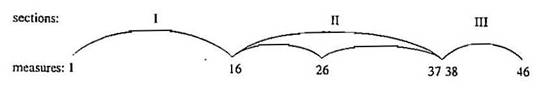

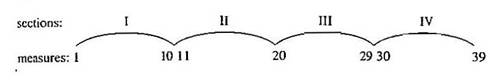

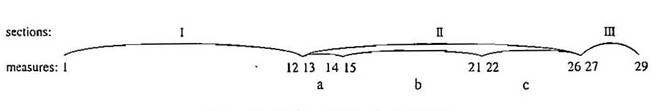

movement. Figure 1 summarizes the first movement’s sectional

design. It is important to note that tempo changes and phrase breaks

create additional possibilities for sectionalization. Further, the manner

in which pitch classes are gradually unfolded in the orchestra and a larger

curve of gradually increasing musical intensity bind sections I and II into a

single larger unit.

Figure 1: Sections in Poème, Mvt. I

Example 2: Poème, Mvt.

I, m. 10, solo viola

Karel Husa POÈME © 1959

Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG © Renewed All Rights Reserved Used by permission

of European American Music Distributors LLC, sole

Constantly changing meters

- largely but not exclusively triple, quadruple, and quintuple - are prominent

throughout Movement I. Within the context of this slow, rhapsodic movement

these meters (and the changes in meter) seem relatively unimportant in

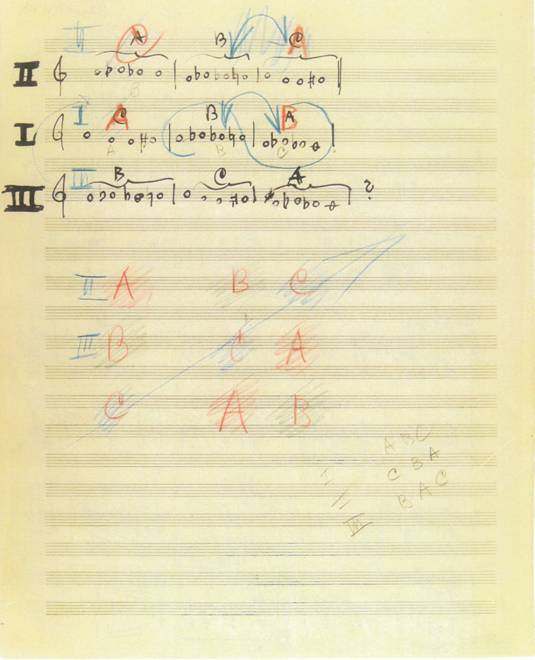

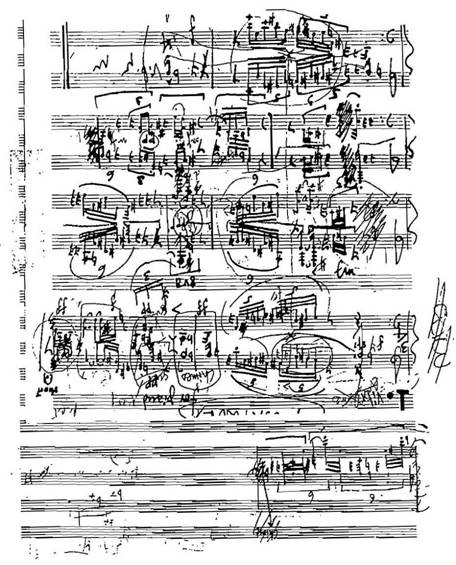

comparison with the overall effect. It is interesting to examine a sketch

for this movement from this perspective (see Facsimile 2). As is evident

in the sketches for Poème and a number of other works from the late

1950s and early 1960s, Husa would write a lead line (the main melodic line) in

black or blue ink. His lead lines at this time show a primary interest in

pitch logic; corrections of rhythm (and even additions of meter signatures) and

additions of dynamics and sometimes instrumentation were done later and in lead

or colored pencil. Here, we see the solo viola line in black ink. The

rhythmic values of

many of the individual

pitches are evident,

but the actual meter signatures

are absent. As with many of the sketches, the initial ideas written in

black ink are covered with many changes and additions in red, green, blue, and

lead pencil, and very occasionally in blue ink. These additions

demonstrate that Husa adjusted pitches, dynamic levels, and orchestration;

however, the absence of meter signatures might best be attributed to the

rhapsodic character of the movement as a whole.

Facsimile 1: Sketch of Tetrachords used in Poème

Facsimile 2: Sketch, Mvt. I of Poème

In his article exploring Husa’s life

and stylistic characteristics of his music, Lawrence W. Hartzell wrote:

in

this work [Poème], pitches, dynamics, row organization, and different

string sonorities are submitted to serialization. From this it can be seen

that it is not the traditional Schoenbergian technique that interests Husa, but

the various serial procedures that have come into being since World War II and

the methodology that they imply.[9]

Even without embarking

upon a comprehensive analysis, one may perceive Husa’s serial

techniques. Example 3 shows the initial twelve pitches heard in the piece;

below the staff, the interval classes between successive pairs of pitches are

shown.[10] The

emphasis on interval classes 1, 2, and 6, the limited use of 3 and 5, and the

exclusion of 4 are indications of Husa’s effort to depart from a neo-Romantic

style into a more dissonant, atonal idiom. Further, the dramatic tritone

at the opening is followed by several registrally distinct chromatic

groupings. The leap in m. 2 from A4 to the D4/E flat4 dyad presents

another tritone.

Example 3: Poème,

Mvt. I, Initial Twelve Pitches.

If one labels the initial tone row P0,

then the solo viola continues with P5 and then P1; the beginnings and

endings of rows are designed not to correspond with the junctures between

phrases. Husa immediately begins to reorder pitch classes within these

rows. The statement of P5 also features two registrally distinct [0,1,2,3]

pitch class sets in m. 4. Note that changes of the contour in P5 (relative

to the contour of the initial P0) unambiguously create the [0,1,2,3]

groupings. The iteration of P1 (mm. 5 – 6, second system

in Facsimile 2) becomes quite angular; almost all

interval class ones are heard as major sevenths or minor ninths. Husa

omits pitch class 11 (the note B) entirely, possibly because of its prominence

in earlier measures, or perhaps because a misnotated B in a sketch of the row

carries into the published version of the work. One might say that pitch

class 0 (the note C) returns “when it should not” as part of the beautifully

symmetrical gesture in m. 6. Row form I1 is then presented (circled

in green in second and third systems of Facsimile 2);

its final tetrachord is given special emphasis by virtue of fortissimo,

repeated pitch classes in m. 8. Row form R1 concludes section I (m. 9, fourth

system of Facsimile 2); here, Husa treats ordering

within the second and third tetrachords with some flexibility. As is evident

in the fourth system of Facsimile 2, the fortissimo A flat3 - G3

insertion was a later idea added to the sketch in green pencil; Husa

experimented with an earlier location (see the scratched-out dyad in green

pencil) before settling on the final location.

Such freedom of ordering continues during section II of the

movement. For example, the imitative passage in m. 10 (Example 2) is

derived most closely from I7. One might think that pitch class 6 (the F

sharp4, later respelled as G flat4) is moved to become the fourth pitch class

in the first tetrachord, though a sketch of this excerpt (not shown in

Facsimile 2) is written directly above a notated row form I7; the initial F

sharp in the row is put into parentheses, as if it were to be omitted. While

the imitation in double stops remains a constant, several other sketches reveal

that Husa expended a great deal of thought as he crafted the viola line of mm.

10 - 13. The reorderings and the selection of row forms and their

transpositions throughout all of the Poème seem to be more closely

related to Husa’s musical preferences than to any particularly systematic or

arithmetic derivational processes. More generally, Husa’s compositions as

a whole show a greater concern with the final, musical result than with

strict allegiance to any mathematical systems. As Hans Hauptmann wrote in

a review of the premiere of Poème:

Karel Husa, the Czech composer now working in

Of course, this is not to say that

Husa’s works are anti-intellectual or were conceived with little

thought. Intricate compositional details emerge during the second

section. For example, the bass line from m. 10 through the end of the

movement traces a chromatic descent from C down to A; the horn solo in the

final measure replicates these four pitch classes, which of course form a

[0,1,2,3] set - an important tetrachordal subset of the row. Just as the

movement and the row began, tritones emerge at the end: the viola has a

prominent E- B flat in mm. 18 -19, and the horn solo begun in m. 19 effectively

concludes with the D4-G sharp4 dyad at the attacca beginning of Movement

II.

Movement II

The second movement, in some ways the 170 - measure centerpiece of Poème,

differs in many respects from the first. Rhythm, meter, tempo,

orchestration, form, pitch organization, and the serial techniques employed

provide significant contrasts. As in the first movement, the sections here

are most clearly heard as a result of changes in orchestration and other non-pitch

parameters. Figure 2 outlines the principal sections along with brief

textural descriptions of each. While the movement is lengthy and complex,

this essay will focus on rhythm and meter, serial pitch organization, and other

interesting compositional procedures found primarily in sections ‘b’ and ‘g.’

Perhaps the greatest contrast between

Movements I and II is in the area of musical time. The temporal

flexibility of Movement I is replaced in Movement II by a faster tempo and by a

constant 2/4 meter throughout the movement. Whereas the first movement

featured many different rhythmic patterns and groupings, the second is limited

almost exclusively to quarter, eighth, and sixteenth notes and rests. At

the same time, a fundamental similarity exists in both movements’ ambiguity of

meter; the simple duple meter of the second movement is not clearly heard

at first, and the sense of 2/4 gradually emerges as the movement proceeds.

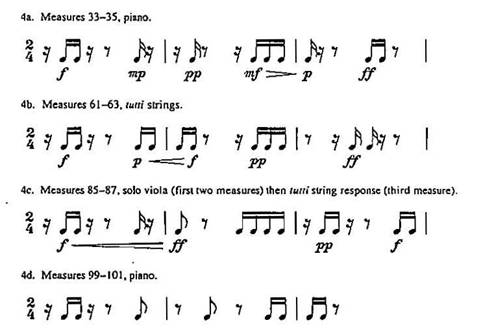

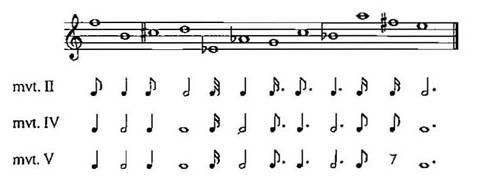

A

syncopated rhythmic pattern evolves throughout the movement, as shown in

Example 4. Example 4a shows the rhythmic interjection heard in the piano

during mm. 33 - 35; it contrasts the even more stark and pointillistic material

in the strings surrounding it, and it foreshadows the later rhythmic

developments. Example 4b is similar; it depicts the rhythm in the tutti

strings beginning at m. 61. In more than one sketch, Husa labels measures

such as those shown in Example 4a with the letters A, B, and C respectively; it

is apparent too that he contemplated reordering these measures (by reordering

the letters representing them in the sketches) and then abandoned the

idea. The first three measures of section ‘f’ are shown in Example 4c;

throughout this section, the viola maintains the rhythm shown or some close

variant, while the responses in the orchestral strings vary more

widely. Note that the dynamics are fairly similar in the passages

represented in Examples 4a - 4c. Section ‘g’ of the movement features an

isorhythmic ostinato accompaniment in the piano, about which more is said

later; its talea is shown as Example 4d (note that this talea is now only 1.5 measures in

length).

Turning

now to pitch, Husa’s serial procedures show some influence from Schoenberg’s later

works in that he treats the three discrete tetrachords as individual

collections within which order may be varied. The pointillistic texture

and colorful use of timbres at the beginning of the movement, however, bear

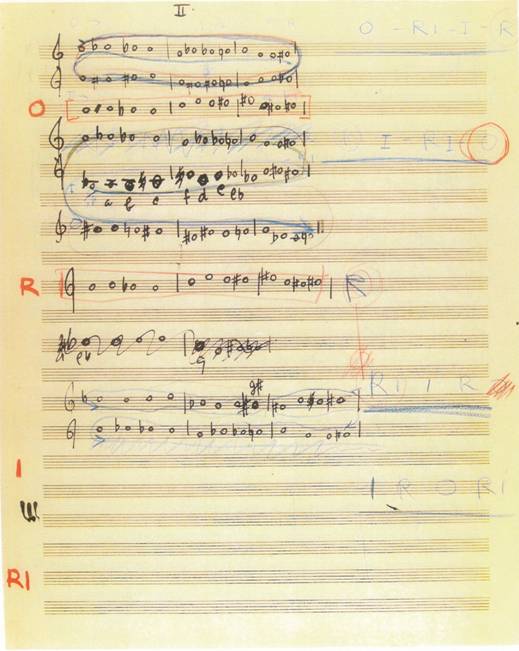

some resemblance to Webern’s writing. The sketch page dealing with row

forms here is straightforward and efficient (see Facsimile 3). Husa writes

out P0 (refer to Example 1 to review its order), then on separate lines he

writes I0, P9, P0 again (but crossed out), I8, P8, P9 again, I1,

mm.: 1-4 5-32 33-35

36-60 61-84 85-99 99-128 129-153 154-160 161-170

idea: a b

c d e f g h i j

a:

horn introduction (completes the

transition from mvt. I to mvt. II)

b:

pointillistic passage; emphasis on

varied timbres and on tetrachords

c:

rhythmic interjection in the piano

d:

continuation of

passage ‘b'; buildup of instrumentation and intensity to all strings and fortissimo

by m. 60

e:

beginning of persistent sixteenth-note rhythmic interplay

f:

more texturally transparent rhythmic interplay between solo

viola and orchestra

g:

ostinato in piano; melodies added in viola then horn;

orchestral strings gradually join solo viola

h:

climactic passage; orchestra gradually thins out and

dynamics grow softer

i:

beginning of transition to mvt. III; harmonics in viola

j:

remaining transition to mvt. III; primarily oboe

solo

Figure 2: Sections in Poème,

Mvt. II

Example 4: Syncopated rhythmic patterns in Poème,

Mvt. II

and P0. These row forms (and their retrogrades)

are among the most frequently used in the movement. In addition, on the

right-hand side of the page, one sees these collections of letters: “O - RI - I

- R,” “R - I - RI - O,” “RI - I - R - O,” and “I - R - O - RI.” Here, Husa

is working out possible orderings of row forms; note that he uses “O” (for

“original”) for the prime form (symbolized in our discussion by “P”). For

example, the movement begins with P0 (mm. 5 - 21), RI0 (mm. 21 - 30), and I0

(mm. 30 - 32). The piano

interjection in mm. 33 - 35

is based upon

row form P9 - although with

several reorderings of pitch classes - and the piano carries eight of the

twelve pitch classes; the orchestral strings

and solo viola complete the aggregate in incisive rhythmic counterpoint

against the piano. Husa then continues the opening process by making use

of R0 beginning with the anacrusis to m.

36.

Facsimile 3:

Sketch of Row Forms for Mvt. II of Poème

Facsimile 4: Sketch of a Passage from Mvt. II of Poème

In addition to carefully disposing

the row forms, Husa also does creative things with re-ordered pitch

classes. The discrete tetrachords comprise first two [0,1,2,3] and then

one [0,1,2,7] pitch class sets. In the beginning of the movement, each

[0,1,2,3] is first heard pointillistically distributed among the orchestral

strings, then it is heard again in a reordered burst of sixteenth notes in the

viola. The same holds for the [0,1,2,7] set, except the reordered

restatement is heard in the piano. The process of restating reordered

tetrachords continues well into the ‘b’ section of the movement.

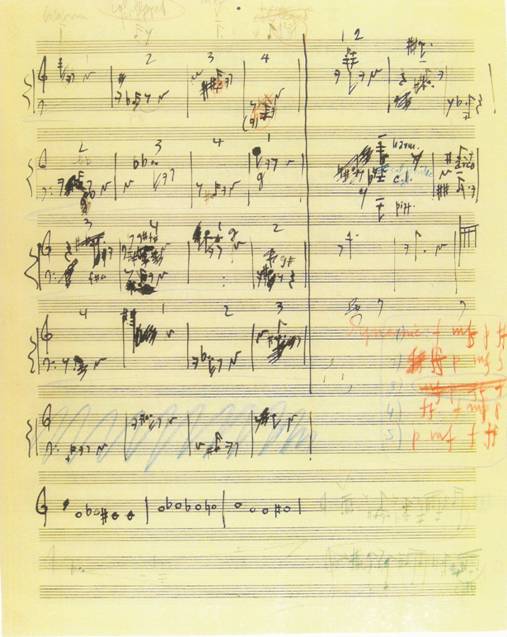

Husa’s careful compositional control

in the opening of the movement extends beyond

pitch serialization into

deliberate ordering of

string timbres, dynamics,

and rhythm. One sketch page in particular makes Husa’s technique

clear: It features a rotational scheme in terms of timbre and also contains

several different orderings of dynamic levels (see Facsimile 4). Figure 3

recasts some of the information, showing measure numbers, timbre types, dynamic

levels, and rhythmic values. Each four-measure segment represents what is

heard in the orchestral strings; the measures in between contain interjections

by the solo viola (mm. 9, 15, and 21) silence (m. 10) or an interjection in the

piano (m. 20). The timbre rotation scheme is a model of clarity: mm.

5 - 8 establish four different string timbres, and each subsequent segment

rotates the first timbre to the end. Each timbre has its own particular

rhythmic value (or at least attack location within the measure); interestingly,

pizzicato would appear to be the exception to this pattern, though in a

compositional draft the rhythm associated with pizzicato articulation is

always as it appears in mm. 8 and 17. Thus, there may be errors in the

rhythms in mm. 13 and 22 in the published score. The dynamic patterning is

less consistent, though, in general, four different levels are always used, and

the louder dynamics are reserved for the pizzicato and harmonic

timbres. It is also worth noting that pitch here involves statements of

tetrachords from P0 or (in the case of mm. 22 - 25) RI0. [12]

The careful organization of both pitch and non-pitch parameters continues after

the piano interjection of mm. 33 - 35, then it gradually is overtaken by longer

notes and a large crescendo leading into section ‘e.’

Figure 3:

Control of Non-Pitch Parameters, Mvt. II of Poème

Section ‘g’ is fascinating and builds to one of the registral and

dynamic high points of the movement. As mentioned earlier, the piano

presents an isorhythmic ostinato throughout the entire section. The

repeated rhythmic pattern is two and a half measures in length, which means

that it is heard exactly twelve complete times during section

‘g.’ Further, this talea, which contains eight attacks, occurs in

association with a color that is thirty-two pitches in length; thus, the

color is heard three complete times during the passage. Each piano

hand carries a single line, and the two hands have identical rhythms (the talea)

throughout the passage. Husa’s color is quite economical; each hand

carries a [0,1,6] pitch-class set, and only four different pitch classes are

heard in both hands together throughout the entire passage, comprising a

[0,1,6,7] pitch-class set. Example 5 shows the first two times through the

talea (thus, one-half through the first iteration of the color). The

hands continue in contrary motion through the remainder of the passage; note

that every vertical dyad is interval class 1. Further, a pattern may also

be discerned in the dynamics - if one considers the talea to have four

rhythmic “groups” (the pair of sixteenths, each isolated eighth note, then the

group of four sixteenths at the end), then one sees that every fifth group is

louder than the surrounding ones. This results in different parts of the talea

emerging throughout the passage.

Example 5: Poème, Mvt. II, Mm. 99–103, Piano

Karel Husa POÉME © 1959

Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG © Renewed All Rights Reserved Used by permission

of European American Music Distributors LLC, sole

In the sketches, at least,

Husa’s interest in compositional techniques more typically associated with the

works of Olivier Messiaen goes beyond the isorhythm just described. The

viola and horn solos during this same passage contain some evidence that Husa

was experimenting with non-retrogradable rhythms.[13] Such

rhythms do not substantially appear in the published score, though they are

evident in the initial entries in both the viola and the horn (see mm. 105 -

110, and mm. 110 - 112, respectively). A separate and unnumbered sketch

sheet reveals the pitch logic of this section: using black ink, Husa

writes out various combinations of P and I row forms, aligned vertically in

such a way that the exact contour mirroring is readily apparent. He

finally arrives at the combination of P9 and I4, on which this section is

based. The fourth and the final pitch classes of each row are circled in

green pencil, and the two circles are connected. These four pitch classes

are the ones used in the piano ostinato. The initial viola and horn melodies

are based on I4 and as the horn finishes its I4 melody, the viola begins a new

melody based on P9 (mm. 117 – 128 in the score). All the while, the upper

strings of the orchestra gradually join the viola, culminating in a fortissimo,

tutti restatement of the P9 melody in diminution (mm. 129 -

133). After this climactic passage, the orchestra thins out and the

dynamics grow softer, leading eventually into the transition to Movement

III. In a manner rather similar to the transition from Movement I to II, the

solo oboe here carries an angular and rhythmically varied iteration of [0,1,2],

concluding with a sustained G5 at the end of Movement II. It is noteworthy

that the first pitch heard in Movement III is C sharp3: once again, Husa uses a

tritone to connect the movements.

Movement III

Movement III reverts to a

more traditional serial approach and recalls several prominent gestures as well

as the slow tempo, and the free, rhapsodic melodic style of the opening

movement. The plaintive character of the final movement is clear at its

outset in the long passage for solo viola. Despite its wide leaps and

range, this subdued melody has a lyrical quality perhaps because of its simple

muted, bowed timbre and its freely flowing rhythms.

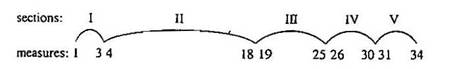

Form

in the final movement is articulated by orchestration (see Figure

4). Sections I and III feature the solo viola. Section II is

characterized at first by interaction between solo viola and piano, followed by

a slightly longer subsection with full orchestra and little or eventually no

material in the solo viola. The concertante passages here differ

from those of the first movement in that they are more simple and lyrical, and

the viola sonorities are restricted to arco and con sordino.

Figure 4:

Sections in Poème, Mvt. III

Movement III is similar to Movement I in

its constantly changing meters, but a somewhat wider variety of meters is

encountered during the solo viola passages, while those including the piano

and/or orchestra are largely in triple or quadruple meters. The sketch of

this movement is similar to that of Movement I - Husa apparently wrote the solo

viola line first, using black ink. Here, however, much of the solo viola

line appears to have been notated in simple quadruple meter at first, then some

rhythmic values were altered to create the changing meters. Some meter

signatures were added later in pencil, which appears to have been the preferred

writing implement used toward the end of the creative process. The

sketches of the piano and orchestral material, all of which are in colored

pencil (red, blue, or green), show densely drawn musical gestures that bear

little relation to the meters found in the score itself.

The serial technique in this movement is

more conservative than in the others, although Husa does repeat pitch classes

and frequently makes use of overlapped rows in which the final pitch class of

one row form simultaneously acts as the first pitch class in the next - a

technique reminiscent of Webern’s approach. One interesting facet of the

row use in this movement is that Husa goes to some effort to conceal its

relationship with that of the first movement (the original row for this

movement, shown as the third line in Example 1, is not actually heard in the

movement). Example 6 shows the initial fifteen pitches heard in the

movement and reveals several interesting features. First, this disjunct

succession of pitches turns out to be row form I6, relative to the P0 shown in

Example 1. A sketch page for this movement makes these relationships

clear: Husa notated here the original row for this movement (labeled “O”

as shown in Example 1). Two staves lower, he notated what we have referred

to as I6 and it is labeled “I.” To the left of this staff, he wrote the

word “Begin.” Returning to Example 6, it is worth noting that Husa repeats

pitch classes D, F sharp and F before moving on to complete the row. The G

sharp at the end simultaneously functions as the first pitch class in the next

row form encountered, I1.

Example 6:

Poème, Mvt. III, Initial Fifteen Pitches

Without reviewing all of the many row

forms encountered in the third movement, it is worth noting that the viola and

its accompaniment each retain their own row forms (unlike the second movement)

and there is little “sharing” or dividing rows among the performing

forces. Similar to Movement I, the tone-row beginnings and endings here

are designed not to correspond with the junctures between phrases. Once

more as in the first two movements, the selection of row forms and

transpositions seems to be more closely related to Husa’s musical preferences

than to any systematic or arithmetic derivational processes.

Thus, Husa designed his Poème as an

arch, with Movements I and III evincing many similarities and Movement II

contrasting in many ways. The pitch logic for all three movements is

created via tightly-related twelve-tone rows built from three tetrachords and

by experimentation with ordering, overlap, and omission or repetition of pitch

classes. The second movement features additional compositional techniques,

including serial ordering of timbres, rhythm, and dynamic levels, isorhythm,

and occasional use of nonretrogradable rhythms. Such organizational

techniques are used freely as simple compositional tools that do not detract

from Husa’s own characteristic style. Poème features intensely

lyrical solo lines and colorful orchestration, yet its serial constructs mark

an important change in Husa’s compositional technique. The work also is

Husa’s first major “concerto” and therefore is an important composition in a

genre that later became one of the composer’s favorites.

Mosaïques

Another important genre in Husa’s ouevre

is works for larger instrumental ensembles, be they winds and percussion or

full symphony orchestra. Mosaïques is Husa’s first serial

composition for large ensemble. Commissioned by the Hamburg Radio, the

composer conducted the premiere of this five-movement work on

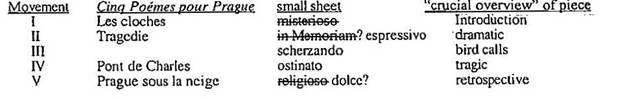

While the five movements in the

published version have no individual titles, the sketches show that Husa did

consider titling individual movements (see Table 1). As is evident in the

projected titles, and of course in the conversation with Robert Rollin, as

quoted earlier, Husa’s score evinces a great concern with orchestral

colors. Radice writes: “More than any of his works to this point, Mosaïques

employs each of the orchestral choirs fully and effectively,”[17]

and, in a personal letter to Husa, dated

Table 1: Movement

Titles for Mosaïques, As Found in the

Sketch File.

When

compared with those for Poème, the sketches for Mosaïques include

a larger number of sheets with tone row manipulations and/or with sketches

working out a specific compositional problem, and fewer recognizable complete

drafts of individual movements. On the other hand, the sketch file for Mosaïques does include three neatly written pages that

reveal some important details from each movement. What we will be calling

the “crucial overview” may well have been Husa’s own notes for a lecture on the

work.

Movement

I

Husa’s interest in color is perhaps most

evident in Movement I, whose provisional title, “Les cloches,” aptly describes

the instrumentation as well as the colors heard. The movement originally

was scored for xylomarimba, vibraphone, chimes, suspended cymbal and gongs,

celesta, harp, and piano; however, a note appearing along with the sketches and

manuscript score reads as follows: “Marimba should be used in Mosaïques

(not Xylomarimba).” The note, written in Husa’s hand and signed by him, is

dated

Figure 5: Sections in Mosaïques,

Mvt. I.

Measures 1 - 10 sound introductory and are

Webernesque in their delicate timbres, pointillistic texture, and angular

gestures, as mentioned by Rollin in the excerpt from “A conversation with Karel

Husa…” cited earlier. Example 7 shows a transcription of Husa’s notation

of the original tone row for Mosaïques (P0) along with its inversion;

the numbering of the pitch classes and mirror inversion are written carefully

by the composer. Interestingly, the introduction does not contain these

row forms; rather, it features row form R11 then a portion of P11. The

sketches contain Husa’s notation of P11 and I11; they are written exactly as

were P0 and I0, except down one half step. D4, the axis of symmetry, is

clearly heard in the chimes in mm. 1 and 6, perhaps bringing this important

pitch to the fore. While one can find suggestions of R11 in mm. 3 - 6,

Husa does make some use of reorderings here. Since it concludes R11 and

then begins P11, the tritone D - A flat is heard in mm. 6 - 7. In mm. 7 -

8, one hears the first portion of P0, though it is reversed with a Webern-like

palindrome in the piano. P0 does not come into full fruition so much as

Husa simply alludes to it, returning to the D - A flat tritone in m.

9. This tritone is heard prominently - indeed, exclusively, with the

exception of a grace note - in mm. 9 -10. These measures, rather static

(yet unstable) in pitch-class content, represent a transition ending the

introduction and announcing the beginning of section II at m. 11. The D -

A flat tritone forms the first two pitch classes in both P11 and I11, thus

creating a suitable transition.

Example 7.

Mosaïques, Transcription of

Sketch Showing Row Forms P0 and I0

What I will call section II, mm. 11-20,

begins with a melodic iteration of row form I11 in the

marimba, borrowing the A4 from the vibraphone to form a complete aggregate in a

single measure. The transitional D-A flat tritone carries over and

accompanies in the vibraphone and celesta. Over the course of just three

measures - mm. 12-14 - Husa introduces row forms R0, I10 (twice) and

P6. The chimes continue to present an important pitch - E flat4 -

during the second beat of m. 14, followed by an E flat-A tritone in the

vibraphone and marimba which is attacked on beat three and sustained for almost

four beats. The shift to E flat4 and to the E flat-A tritone is

significant, as these introduce row forms P0 and I0, which are then presented

simultaneously in the two hands of the piano and are completed by the D-E dyad

in the celesta on the downbeat of m. 15.

The

passage from the introduction of P0 and I0 in m. 14 through their retrograde,

concluding in m. 26 becomes remarkably complex, replete with many textural

layers articulating repeated patterns quite rapidly. The effect -

especially around the midpoint of the movement, where the retrograde begins -

is a quasi sound-mass in its layering and overall fabric of sound; the

instrumentation, repeated patterns and brief ostinati lend an almost Eastern

quality to the passage.

Rather than journey measure by

measure (and row by row) through this passage, I am electing to let an

interesting sketch by Husa stand for itself - see Facsimile 5. This sketch

page is published in the collection Notations by John Cage.[19] Some

explanation is in order. A note attached to Husa’s sketches, in his hand,

reads, “Esquises de Mosaïques ? - no. 5 given to John Cage (

Facsimile 5:

Sketch Page of Mosaïques, from

Notations score Collection by John

Cage

A

number of interesting features are present here. First, the sketch

features a lead line in what appears to be black ink; the sheet from which this

is cut out has notations of P0 and I0 in

black ink immediately above what is seen here (similar to what is transcribed as Example 7). This sketch is

extraordinary and efficient since it presents a compressed digest of the most important gestures of

the passage. The first system and all but the final flourish of the second

present the original musical ideas; from the final flourish to the end, the

ideas occur in retrograde, with some minor modifications. Mirror symmetry

is evident - for example, E flat4 is the axis for the first chime attack, then

again on the final sixteenth of the first full measure, leading to a reiterated

E flat4 on the next downbeat. In the remainder of this measure, P0 and I0

are presented such that A3 is the axis, though of course E flat may be heard as

a secondary one.

Measure two is a good example of a

passage that looks somewhat symmetrical due to contrary motion, but in fact is

not mirror symmetrical. Here, Husa distributes P0 with considerable

reorderings across the hands. In this movement as well as others, Husa

uses the chimes or sometimes celesta to complete the aggregate, or to launch a

new one. An interest in aggregate completion, which became somewhat less

important to Husa in later works, is evident in the first two complete measures

(and the final E flat4) of Facsimile 5. In summary, the gestures seen in

the facsimile are the most important ones encountered in the middle portion of

the first movement. They are heard many times in changing temporal and

textural contexts and combinations. Measures 26 - 29 complete what will be

called section III, and are of course a retrograde of mm. 11 - 14 which began

section II. Measures 30 - 39 conclude the movement quietly and gently

with a retrograde of mm. 1-10.

Movement

II

Movement

II provides a striking contrast in orchestral colors, as it features the string

section - both solo players and the full sections - and the xylophone, celesta,

and harp play a small but structurally important role. As shown in Figure

6, the movement falls into five sections suggesting an arch design in the

similarities between sections I and V and also II and IV. The introduction

consists of string gestures using a combination of row forms P4 and

I4. Example 8 is a transcription of a related sketch; essentially, nine

pitch classes from I4 - those connected by slurs - form the three melodic

trichord gestures heard in the solo violin, ‘cello, and viola. The

accompaniment is drawn from P4 and in particular from those pitch classes that

are circled. The final attack heard in the introduction, G sharp5 in the

viola, completes the aggregate.

In a manner similar to section I,

section V consists of the combination of two row forms

- here, R4 and RI4. Just as I4 did earlier, RI4

provides the nine pitch classes projected

melodically in a pitch-class retrograde of the nine from the

beginning. The accompaniment in section V is a bit different from that of

the introduction, but it still projects P4, only in retrograde. The

movement concludes with a sustained G3 in the solo ‘cello, completing the

aggregate launched at the outset of the section.

I: Introduction; gestures using a

combination of row forms P4 and I4; ends with aggregate completion (G# in

viola)

II: Expressively thematic, row forms P4 and

R4 in a myriad of configurations and rotations

III:

Wide-ranging, near mirror-symmetrical verticalities with aggregate completion and

initiation in celesta; row forms P0 and I11 and their retrogrades are

projected; row forms R0, I10, and three pitch classes from I2 projected in mm.

23-25

IV: Thematic

viola and ‘cello duet; row forms I2 (from section III) and then R12 are used

V: Mirrors

section I, but loosely in retrograde (combines row forms R4 and RI4); ends with

aggregate completion (G3 in ‘cello)

Figure 6: Sections in Mosaïques, Mvt. II

Example 8:

Mosaïques, Mvt. II, Sections I

and V, Transcription of Sketch (row forms P4 and I4)

Sections II and IV are similar in

their rhythmically diverse yet dramatically sustained lines. As mentioned

beneath Figure 6, the second section of the movement consists of row form P4

and its retrograde, arranged into a variety of configurations. Example 9,

a transcription of another sketch, provides some insight into Husa’s thought

process. Row form P4 is shown again, now partitioned into

trichords. As sometimes is his practice in such sketches, Husa then

numbers the twelve pitch classes. Each trichord is then assigned a

rhythmic profile - that is, the time span over which the three pitch classes

are to be projected. Note that the quarter note duration of the third

trichord may be thought of as a set of eighth-note triplets, or even as a set

of sixteenth notes. Each trichord is also assigned a dynamic level, with

trichord number two being either piano or pianissimo. Next,

Husa fleshes out pitch class reorderings - see the string of numbers. Row

forms P4 and R4 are projected in order. The 3 2 1 concluding R4

simultaneously launches a reconfigured P4 - each trichord contains its third

member, then second, then first. The

same process then occurs, but in retrograde. At the bottom of Example 9,

Husa’s sketch of the initial P4 and R4 is shown. The trichord

design is easily perceived, and the temporal design conforms with his initial

conception shown nearer to the top of the sketch, with occasional small

alterations of the rhythms, especially those of the first two

trichords. The sketch is played out quite clearly in section II of the

movement, along with interesting changes in instrumentation bringing out the

different trichords. A number of additional pages in the unindexed sketch

file confirm that Husa’s thought continues in this direction throughout section

II.

Example 9:

Mosaïques, Mvt. II, Section

II, Transcription of Sketch (row form P4)

Section IV, comprising mm. 26 - 30 and

carrying over into m. 31, is performed by only two instruments: solo viola and

‘cello. Its pitch logic is quite straightforward, continuing row form I2

which had been initiated in m. 25 in the harp, then turning it around into RI2

in mm. 28 - 30. The rhythm, while seeming to be freely syncopated, was the

product of precompositional planning as well. Example 10 is a

transcription of a small sketch in which Husa writes out row form I2 and

associates specific note values with each pitch class. The viola and

‘cello parts in mm. 26 - 27 adhere almost exactly with Husa’s plan, if one

allows a bit of freedom at the glissando in the ‘cello. Row form

RI2 also holds fairly close to Husa’s sketch, again allowing some margin of error,

especially near the glissando.

Example 10: Mosaïques,

Transcription of Sketch of Row Form I2 Pitch Classes with Associated Temporal

Values (Note that the row form in question for Mvt. IV is P4, not I2, but the

temporal succession still applies and appears in a different sketch.)

Section III,

the peak of the arch design, is radically different music than that of the

other sections. In just the first two measures (mm. 19 - 20), Husa

presents row forms P0 and I11 in a seemingly bewildering array of registers,

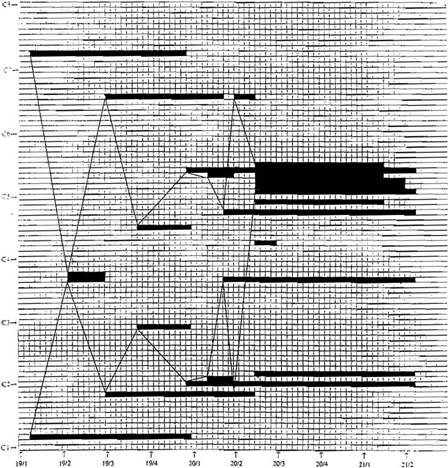

instruments, dynamic shadings, and rhythms. Example 11 is a graph of mm.

19 - 21, showing pitch vertically and elapsed time horizontally; the gradual

deployment of dyads is clearer there. Initially, P0 is the higher pitch in

each dyad, though at order positions 5 and 6 (using Husa’s 1 - 12 numbering),

both row forms contain the pitches C and F and they perform an exchange as P0

becomes the lower member of the next couple of dyads. The passage conveys

near mirror symmetry about an axis of G sharp3/A3, though some pitch classes

are in different octaves. Each dyad has its own dynamic level (with

duplications) and there does not appear to be a strict temporal logic at

play, though the last few dyad attacks do occur at closer and closer time intervals. The

first nine pitch classes of P0 and I11 are presented in this manner, and then

the celesta wonderfully completes both rows with a burst of major and minor

second clusters. These clusters then take on a new role, pivoting to

become the first three pitch classes in the retrogrades, R0 and

RI11. Afterwards, the remaining nine pitch classes of R0 and RI11 are

projected in a manner similar to that heard in mm. 19 - 20 (see Example

12). Here, the temporal logic is more transparent: the attacks of the

dyads grow further and further apart, moving from a distance of a single

sixteenth note to two, three, four, and so on. As these row forms are

completed in m. 23, the celesta reenters with an echo of the earlier clusters,

followed in mm. 24 - 25 with row forms R0 and I10. As shown in Example 12,

the large chords are sustained until the very end of m. 25.

Thus, the second movement of Mosaïques

evinces a wide-ranging variety of compositional techniques. Sections I and

V are created via vertical and horizontal presentations of row forms related by

inversion. Combinatoriality does not play a role, but each section

concludes after the aggregate is completed. Section II features an

interesting pitch-class rotational strategy - also projecting row form P4 and

then its retrograde - and dynamics and temporal values are also serially

organized. Section IV is

similar, though less

complex and bearing

a different precompositional temporal

organization. Section III is about gradual dyadic additions and registral

symmetry, with some minor asymmetries resulting from octave placement.

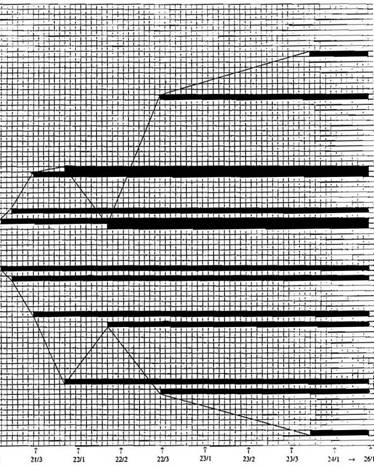

Example 11 and 12: Graph of Mosaïques,

Mvt. II, mm. 19-24. Pitch space (the vertical axis) is calibrated in

half steps at one square each. The

numbers in the left margin are standard octave numbers, where middle C is

labeled as C4. Time is shown along the

horizontal axis; the figure ‘19/1’ refers to m. 19, beat 1 and

so forth.

Each square thus represents a thirty-second note.

Movement

III

The third movement

begins with piano, percussion, and woodwinds, immediately establishing the

colors to be featured throughout the movement. Eventually, the entire

orchestra comes into play, though the strings do not enter until almost halfway

through the movement, and even then they play a minor role. Movement III

may be heard in five sections, creating a rather rondo-like form, as shown in

Figure 7. Section I begins with a three-measure introduction, after which

frenetic melodies are heard in the woodwinds.

In the “crucial overview” of the entire work, Husa writes “bird calls”

as representing these melodies, also writing down the names Janáček and

Messiaen. The additive and repetitive nature of the melody heard in the

piccolo in mm. 4 - 8 typifies a technique found in some of Husa’s later serial

works. An early sketch shows an even more comprehensive additive process

(see Example 13). The transcription clearly shows Husa gradually adding

pitch classes - and eventually eliminating the early ones - until all of row

form P3 has been presented. In the published score, Husa modifies the

comprehensive additive treatment in favor of chords articulating five or six

members of the prevailing row while the woodwind melody presents the rest in an

additive manner. Section I dissolves into a passage with rapidly repeated

notes (and chords); the woodwind melodies resurface at m. 34, accompanied by a

metronomic wood block.

Figure 7:

Sections in Mosaïques, Mvt. III

Example 13: Mosaïques, Mvt. III, Transcription of Sketch Showing Additive

Pitch-Class Process

Section

II is characterized by a melody in the strings and brass, accompanied by

woodwinds continuing frenetic rhythms, now as an obbligato accompaniment, along

with the metronomic percussion. Serially straightforward but metrically

complex, section II holds to alternating five-eight then seven-eight meters

throughout, heard in groupings 2 + 3 and 4 + 3. Interestingly, in an early

sketch for the movement, a black ink lead line contains no meter signatures,

but Husa does write 2 + 3 + 4 + 3 + 2 above the score, and the melody reflects

these groupings. A later iteration of the passage, notated on different

paper in blue ink, shows a four bar pattern: two-eight, three-eight, four-eight

(later simplified to two-four), then three-eight. Husa later used a red

pencil just above the passage, marking 5 then 7 and adding brackets at the

beginnings of two-eight with three-eight then two-four with three-eight

respectively. Thus, the metrical design of the passage gradually took

shape over time.

Section

III is a brief five-measure “break” where the woodwinds articulate their

frenetic, angular melodies, accompanied by the metronomic wood block and other

instruments. Section IV follows with the same basic idea as was discussed

above in relation to section II, though here the brass section is silent and

the melody is presented by piano and strings using glissandi, and the

alternating meter pattern is the reverse of before – 7/8 then 5/8. Section

V is coda-like, bringing back the repeated notes (and chords) along with a

brief iteration of the frenetic woodwind melody, though now in the

strings. The end result is a formal design that may be interpreted as

rondo-like: A B A’ B’ A’’.

Movement

IV

Movement

IV may be heard as a lengthy and complicated but still quite discernable

ternary form. The main idea in the outer sections is a series of brutal,

aggressive chords presented in varied, rhythmically incisive ways. The

chords are made up of four prime row forms occurring simultaneously: P1,

P5, P7, and P8. Facsimile 6 shows the logic found in the “crucial

overview” of the piece. As can be seen, each chord contains one pitch

class from each of the four row forms. The chords are then numbered: the

odd-numbered ones occur principally in the brass while the even-numbered ones

are heard mostly in the woodwinds and strings. After the piece opens with

these chords and little else, Husa retains them as accompaniment to an angular

melody in the lower brass, beginning two measures before rehearsal

‘D’. This melody adds row form P4 to the mix, and its rhythm was generated

by pre-compositional organization (refer back to Example 10). The melody

continues in such a manner for some time.

The

middle section is quite different from its outer counterparts in that it

features a more lyrical melody, but still with strong punctuations in the

accompaniment. Here, a repeating metric pattern of 3/8, 4/8, 5/8, 4/8, 3/8

occurs, cropping up as simply 3 + 4 + 5 + 4 + 3 in the sketches. The

similarity to the metric scheme in the contrasting sections of the previous

movement is obvious. Aside from metric complexity, Husa makes use of just

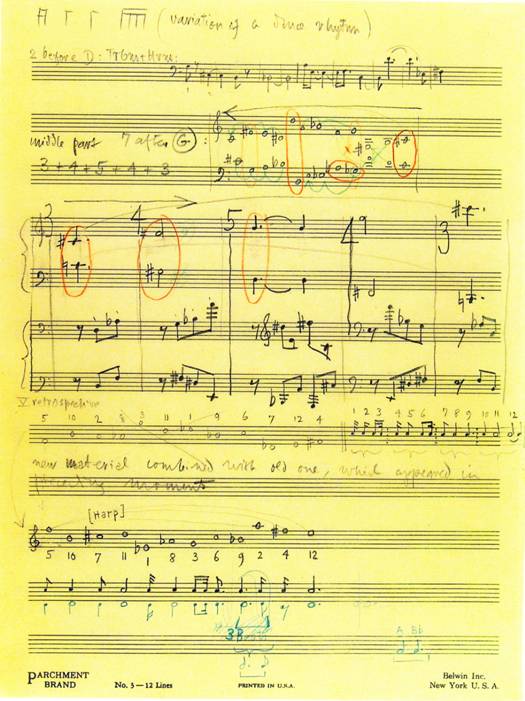

two row forms - R9 and RI10 - in a very free way (see Facsimile 7). Note that

“middle part, 7 after G:” points directly to row forms P9 and I10, notated to

the right. Those pitch classes circled in red are used in the melodies

written on the top two staves below the row notations, while those pitch

classes marked in green are used in the accompaniment. To be even more

specific, let us assume that the higher of the two melodies is accompanied

by the lower of the two accompanimental strata. The melody begins with C sharp, the first

pitch class in row form R9; it is accompanied by a B and then an F, which

represent the second pitch class in R9 and then the third pitch class in RI10 -

note the crossed arrows in the row diagram. The next pitch class in RI10,

shown as G flat3 in the row diagram, is circled in red and also in

green. It forms the next note in the melody (m. 2) as well as the first

pitch class in its three-note accompaniment, which is F sharp3 - D sharp3 - E2

in the score and is seen as the green-circled G flat3 skipping to E flat3 and

then E3 in the row diagram. The process continues in like manner and then

partially retrogrades itself. The flashes of mirror symmetry and

almost-mirror symmetry are not coincidental, as mirror symmetry plays an

important role in many passages in many of Husa’s works. One thinks here

of the important influence of Béla Bartók.

Movement V

The

calmer, almost elegiac fifth movement represents an interesting amalgamation of techniques from

earlier movements - especially Movements I and II. Following Movements III

and IV, in which the full orchestra is unleashed, the final mosaic also uses

the entire orchestra, though in a quietly retrospective manner (as evidenced by

the descriptive title “retrospective” found in the “crucial

overview”). Figure 8 presents the sectional design of Movement

V. During section I, the muted violins carry a sustained melody and the

harp, xylophone, marimba, and piano contribute brief interjections. The

violin melody consists of presentations of row form I2 and its retrograde; its

temporal logic is seen in the final line of Example 10: the succession of note

values is simply a doubled version of the succession from Movement II with the

exception of an eighth rest rather than what should be an eighth note as the

penultimate value. The melody in Movement V follows this succession (and its

retrograde) quite closely. Given that this melody projects the same row

forms and durational proportions as that from Movement II, mm. 26 - 30, it

represents a striking return of the earlier melody, especially when following

on the heels of a loud, aggressive ending to Movement IV. The marimba

interjection in m. 6 bears a striking timbral and pitch class similarity to a

passage in the marimba from Movement I, mm. 19 - 20.

Facsimile 6: Sketch of Chords from Mvt. IV of Mosaïques

Facsimile 7: Sketch of a Passage from Mvt. IV of Mosaïques

Figure 8: Sections in Mosaïques, Mvt.V

As is the case in the opening of many of Husa’s movements, the line

between sections I and II is deftly blurred. Here, section II contains

three subsections, represented by the letters a, b, and c. Subsection ‘a’

is only two measures in length, but it is important. In an obvious return,

Husa brings back the large verticality from the third section of Movement

II. Similarities to the earlier passage include range extremes,

approximate mirror symmetry, and gradually added dyads. The passage here

in Movement V differs in that it is a half step lower and the orchestration is

changed – almost all pitch classes are presented in the winds, along with

punctuations in the harp and piano. The aggregates are completed in a

manner similar to Movement II, although here the marimba, vibraphone, and

celesta all participate. Finally, the passage in Movement V projects a

clear cut accelerating durational pattern as the dyad attacks, initially

The large sonority assembled during

subsection ‘a’ recurs in subsections ‘b’ and ‘c’, with the very lowest note

changed from C sharp1 to C1. Thus, all three subsections are tied together

into a large section II. Subsection ‘b’ features an interesting

orchestrational development as the

strings sustain the sonority while the winds attack it

homorhythmically in groupings of one, two, four, then two attacks with varied

dynamic levels. The attack patterning, an important characteristic in most

all of Husa’s ouevre, is similar in its morse-code-like groupings to

passages from Movements III and IV. While the strings and winds are

concerned here with the large sonority, the percussion, celesta, harp, and

piano present motives from Movement I in a quite literal though more

fragmentary return.

Subsection

‘c’ begins at the anacrusis to m. 22, where the strings and winds overlap their

respective release and attack of the large sonority; the winds then take over

sustaining it while the strings rest. The wind releases occur in an

almost-additive pattern of two then 3, 4, and so forth sixteenth notes apart,

while the piano and harp present melodic fragments that begin with a single

sixteenth then grow in length through 2, 3, 4, 5, and more

sixteenths. Measures 25 - 26 have one foot in subsection ‘c’ and the other

in the larger section III. With the lone exception of the violas, one

hears just the notes C, C sharp, D, and D sharp, pointillistically articulated

during these two measures. This characteristic continues, although with

more sporadic attacks, during the final three measures of the piece. A

point of articulation can be heard at m. 27 simply because the flute enters

with a plaintive three-measure solo, projecting row form P6 (but not in its

entirety) to conclude Mosaïques as it began - gently and quietly.

Summary and

Conclusion

Both Poème and Mosaïques

contain compositional techniques that continue deeply through Husa’s entire ouevre. The

composer’s interest in sound color is most evident in his creative use of

percussion, various string effects, and the serialization of timbres and

dynamics. Textures are enormously varied, ranging from single instruments

to entire ensembles; in places, his textures might even be characterized as

pointillistic. Husa’s avid interest in musical time is evident in many

ways: meter signatures often function more as temporal/organizational

conveniences than as clearly articulated entities; surface rhythms vary from

rapid repetitions to lyrical sostenuto writing; and some passages convey

stasis, while others feature frenetic motion. Husa also uses some serial

durational procedures, usually somehow related to the pitch row. The

Messiaen-like isorhythm and non-retrogradable rhythms found in Poème

seem to be passing experiments that do not turn up regularly in later

works. Neither Poème nor Mosaïques contain Husa’s well-known

aleatoric outbursts, though their more rapid rhythms may foreshadow this

technique.

Much

may be learned from Husa’s approach to pitch. He experiments with

generating twelve-tone rows from tetrachords and trichords; the evidence in his

later sketches shows that he continues to generate twelve-tone rows by using

trichords. Even in the sketches seen here, his rows show an interest in

registral specificity by virtue of their melodic design, unexpected leaps, and

changes of direction. Husa also shows an interest in aggregate completion,

though not by using a systematic, combinatoriality-related procedure. His

choices of row form are made for aurally apparent reasons - one can hear the

ways in which he juxtaposes or superimposes P and R or I row forms. Husa’s

lifelong interest in pitch symmetry and mirroring is already evident in the

works under study here, both in the more abstract sense of combination of P and

I forms in the sketches as well as in concrete, clear vertical symmetries heard

especially in Mosaïques. We also note the great freedom with which

he uses reorderings and occasional omissions of pitch classes, processes in

which he begins with just one or two pitch classes and then gradually adds

more, and rotational schemes that take on more important roles in Husa’s later

works. In the end, however, we see that Husa’s interest in the final

musical result seems to outweigh any systematic or mathematical derivational

procedures.

Husa’s

nontraditional approach to musical form is evident in Poème and Mosaïques,

as are his use of blurred lines and dovetailing of sections. In a personal

conversation with the author, Husa noted that he treats each piece as a new

challenge - not only to steer clear of tradition, but also to avoid overt

repetition of his own ideas.

In

summary, Poème and Mosaïques are impressive examples of Karel

Husa’s eclectic approach to composition, presenting the contradictions between

adherence to compositional systems and freedom. Systems encountered in

both works - perhaps a manifestation of Husa’s early training as an engineer -

could appear to create a degree of rigidness. However, formal freedom, use

of serial techniques but without strict order limitations, rhythmic élan, and

especially Husa’s sure sense of timing and affective high points ensure that

any such perception of rigidness is tempered by the compositional freedom in

the hands of a master.