Debussy, Wolpe and Dialectical Form

Matthew Greenbaum

It is hard to imagine music more dissimilar

than that of Claude Debussy and Stefan Wolpe. And yet Wolpe's approach to form

owes a great deal to Debussy, who - as I will try to show - first elaborated

the dialectical scheme so common in Wolpe. By examining the historical

evolution of this hitherto unlabelled form we can better understand Wolpe's

indebtedness. We shall use as illustrations a preliminary example from Don Giovanni, then

Debussy's "Des pas sur la neige" and finally Wolpe's Form for piano.

In the most rudimentary dialectical form a

musical idea progressively generates its antithesis: a gradually emerging

contradictory idea. (1) Conflict, contrast, and opposition:

all are types of antithesis. Just as other aspects of music, antithesis also

had a historical development, which culminated in new form-generating

structures in late-19th century music, as I will try to demonstrate below. This

was a result of the increasingly subjective musical aesthetic that was to find

its full flowering in Symbolism and which required a new vehicle of

representation once it had transcended the structural and representational

confines of common practice tonality.

While a work like "Des pas sur le

neige" can be analyzed in many ways - the most inviting being, perhaps, a

modified strophic structure or rounded binary form - these descriptions do not

account for its evolutionary dynamic. I maintain that its underlying

dialectical process is powerful enough to reduce details of formal repetition

to epiphenomena; or rather, that the dialectical process appears to produce

form as it moves through time. Even though one may bridle at the use of the

word 'form' to describe what at first might appear to be only a process, the

totalizing effects of this process are impossible to ignore.

You may have assumed that Hegelian logic is

the source of this dialectical thinking; but it is difficult to determine the

direction of influence as far as Hegel and his musical contemporaries were

concerned. Beethoven owned a few of Hegel's works although it is unclear to

what extent he made use of them. (2) In fact, Beethoven and Hegel both

drew upon conventions of musical rhetoric which themselves originated in the

classical tropes. (3)

The Enlightenment organicism of Kant and

Goethe valued artworks that developed from a motivic kernel, and which seemed

to be driven by an inner necessity comparable to a biological process. No

detail should be extraneous to the cellular growth of the whole. Beethoven is

heir to this aesthetic. It would seem, then, that the organicist model left no

room at all for self-contradiction. But contradiction had already entered music

with the classical rhetorical figures, which had permeated the logic of Baroque

music as oratorical tropes and which persisted through the Classical Period.

The Baroque fully embraced Aristotle's

definition of rhetoric as a counterpart of dialectic (disputation). The

enthymeme, or rhetorical demonstration, (4) underlay

the Affekten;

contradiction in music was meant to exert the same oratorical force as rebuttal

in debate, but whose object now was the listener's submission to an Affekt

rather than to an argument.

This is borne out in Baroque music theory.

According to Mattheson, the main idea (Propositio)

is to be succeeded by one or more counter-statements (Propositio variate) at last

opposed by the Confutatio,

or resolution of objections "expressed by ... the citation and refutation

of apparently foreign passages. ... Everything that goes against the

proposition is resolved and settled." (5)

Affirming this redendes Prinzip - the "speaking"

or "oratorical" principle in music - Riepel writes, in analogy to the

rhetoric of exegesis: "A preacher cannot constantly repeat the Gospel and

read it over and over; instead, he must interpret it. ... In addition to the

thesis [Satz],

he has at the very least an antithesis [Gegensatz]." (6)

These terms were given to the themes of the sonata movement a generation later

by Forkel (1788), who calls the main theme the Hauptsatz [thesis] and the contrasting

theme the Gegensatz

[antithesis]. (7)

All this antedates Hegel, who, in the Vorlesungen über die

Äesthetik (1820 - 1829) uses similar language to describe

musical contrast. (8) Borrowing Riepel's terms, Hegel sees

thematic contrast as a contradiction (Gegensatz).

Most comprehensively Hegel describes the antithesis (Gegensatz) of consonance

and dissonance as a conflict between imaginative freedom and the necessity of

an underlying harmonic logic. (9) It is in the Äesthetik that Hegel

links the principal of rhetorical conflict with an overarching metaphysics of

time and consciousness.

The naturalism of the Enlightenment had

streamlined the relationship between form and content: the "public"

nature of the late-18th century sonata required that the affective intention

must be grasped immediately along with the form. (Indeed, the dialectic of

tonic and dominant - a closed circle of distance and return - is a rhetorical

figure in itself.) Themes were character types, essentially interchangeable

with operatic figures. The aim was the depiction of human nature; or, rather,

nature in its human dimension. The Kantian sublime was new to this schema,

although the harbinger of things to come.

The representation of the sublime, which

includes everything terrifying and otherworldly, required the employment of

contemporary outer limits of tonality: sequences of diminished seventh chords,

functional chromaticism and modulatory sequences. In Don Giovanni Mozart begins

to press beyond these conventions. Consider the following curious moment, where

the ghostly statue of the Commandatore is about to drag the Don to Hell:

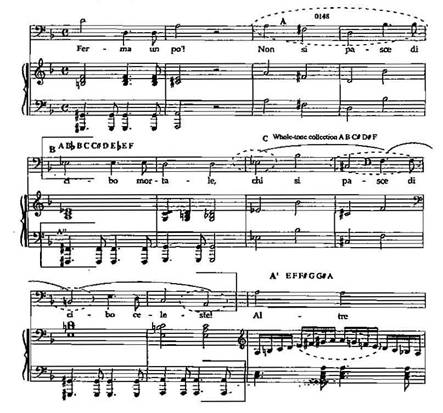

Example 1: From Mozart: Don

Giovanni

The distinctiveness of this passage is the

result of rather startling chromatic and whole-tone implications, brought into

relief by octaves with no explanatory harmonies to support them. Note the:

-

0148 tetrachord (at A).

-

chromatic accumulation in the voice part at B

-

subsequent orchestral scalar figure at A', which completes the 12-tone

aggregate, as does the chromatic bass movement A'').

-

the implied descending whole-tone sequence at C, which also includes a C#/F

dyad at D whose harmonic logic is nearly impossible to grasp by ear.

In the dialectic of Don Giovanni, the carnal

world of the earthly characters emerges from a supernatural world first

enunciated in the overture and concluding in the spirit-ridden scene where the

Don meets his perdition. (The work originally ended here, nicely resolving the metaphysical

conflict, but this solution was considered insufficiently moralistic, impelling

Mozart to add a final sextet). As a result of a new arsenal of compositional

innovations, music vastly expanded its capacity to represent the subjective.

Modulation to heretofore inaccessible key areas (thanks to equal temperament),

Lisztian octatonicism, whole-tone scale expansions of the French sixth chord,

extended chromaticism; all permitted the depiction of novel psychological

worlds. Coinciding with - and indeed linked with - the Symbolist movement, this

panoply of devices allowed the pictorialization of transcendent, infinitely

subtle psychological states. The character contrast of sonata form was subsumed

into metaphysical opposition. The extension, or even abolition, of tonal

conventions offered the possibility of a form based entirely on the generation

of contradiction. The replacement of tonality by other scalar forms and

extended chromaticism, as in Liszt and Debussy, demanded a dialectical logic to

avoid a discontinuous, "inorganic" partitioning of unrelated

materials. But this form required a rhetoric of imagery to make it comprehensible:

the imagery of Symbolism.

Hegel had already made a connection between

musical logic and the symbolic. He describes the logic of instrumental music as

a representation (Vorstellung)

of abstract feelings (abstraktere

Empfindungen) (10); but also as ready to

represent the most varied meanings; a correspondence with the inner self of the

listener who must quickly decode (entziffern)

and grasp its symbolic (symbolisch)

meaning. (11)

Given

our limitations of space it must be pointed out only in passing that it was

Wagner who first made music out of this new rhetoric of symbols. Baudelaire,

whose sonnet "Correspondances" was the exemplar of Symbolism, was a

passionate Wagnerite. (12)

The

Ring

can be understood as a vast dialectic in which the world of the gods and men

emerges from Nature, i.e., the Rhine, only to plunge back in a final cataclysm. (13)

This grand metaphysic is reflected in the basic level of character conflict and

its musical analog, the Leitmotif.

It was Debussy, however, who perfected a

dialectical form without words. Here, he followed Liszt, whose Nuages gris is a daring -

if rather modular - example of the form. The music of Debussy is less a

discourse, in the 18th century sense, than a sounding correspondence with the

natural world. (14) Here, the redendes Prinzip - music

as discourse - has been overshadowed by a new sense of music as object, as a process

resonating with the natural world: organicism enriched by Symbolism.

A "symbolic" music must stand in

opposition to developing variation and other conventional techniques of

development since symbols, sound-symbols included - must be taken in as a

sensuous whole at the moment of their occurrence. Conventional development

would destroy their meaning; they can only emerge and disappear.

"Des pas sur la neige..." (Préludes I #6) is a

completely realized dialectical form. (15) It

evolves from the interpenetration of disparate pitch materials (diatonic,

octatonic, whole-tone and chromatic). Its brief apotheosis, an

"organum" in the G diatonic pitch collection, emerges from this

matrix and stands in dramatic opposition to the prelude's initial D modal minor

tonality. (16)

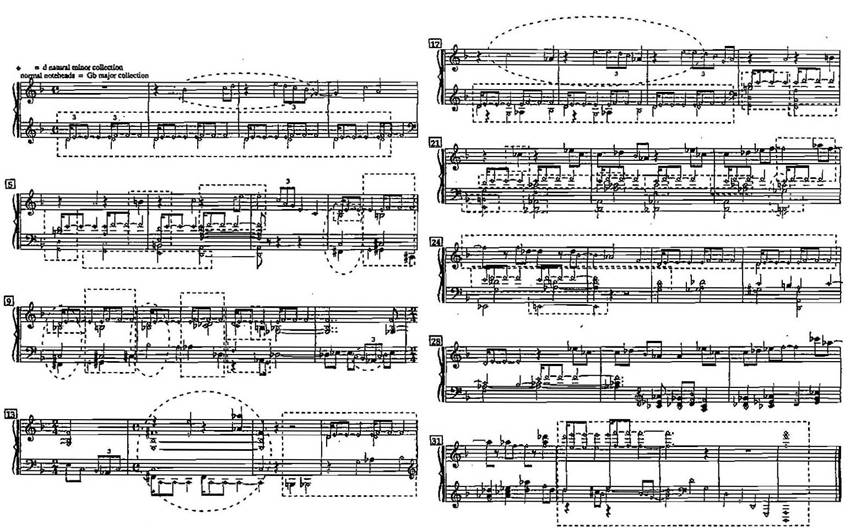

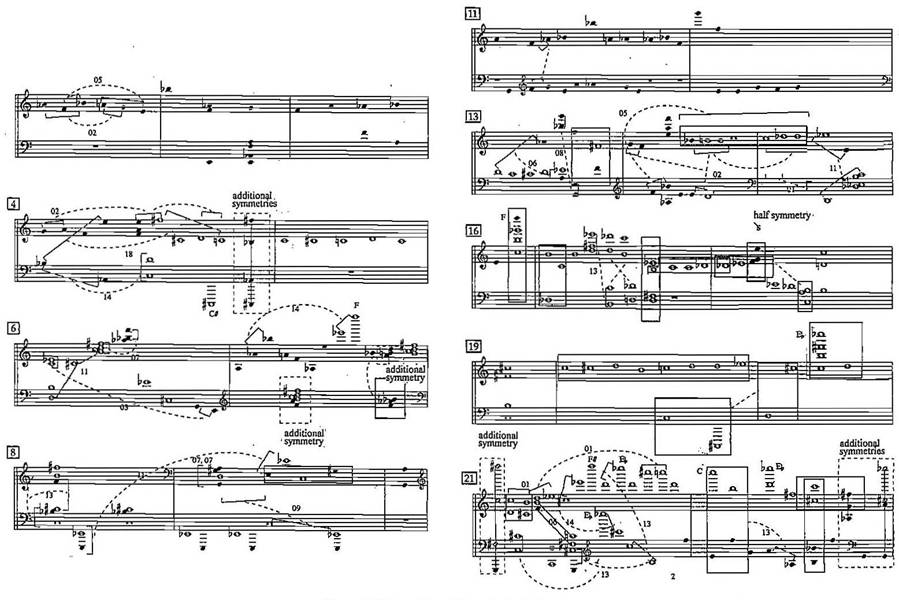

Example 2 illustrates the emergent process in

"Des pas sur la neige". Pitches in the D minor collection are

represented by diamond-shaped noteheads while normal noteheads represent the

emergent G major collection (overlapping pitches E - enharmonic F, and B

diamond-shaped). The whole-tone and octatonic collections, which mediate

between the D and G collections, are indicated by dotted shapes; the former by

dotted circles and the latter by rectangles.

The point of emergence in "Des pas sur

la neige" is signaled by a brief halt in the D E F ostinato figure that

runs through the rest of the prelude. The pitches of this ostinato are shared

by the D minor, whole tone and octatonic collections. This permits a constant

reinterpretation of the figure, as if it were moving through a gradually

changing physical space. (17)

Example 2:

Debussy; Des pas sur la

neige, Pitch Collection Analysis

Diamond noteheads indicate D minor collection. Normal

noteheads indicate G major collection.

Whole-tone collections are indicated by dotted curves and

octatonic collections by dotted rectangles.

The whole-tone set shares three pitches each with

the D minor and G major collections, allowing it to function as a pivot-an

extended French sixth (F# C B D and then E) in mm. 8 to 10 - in relation to the

preceding D minor region as well as the succeeding (enharmonically-spelled) D

dominant seventh chord. This harmony recurs in measures 14 and 15 and again in

m. 23, finally to be resolved in the emergence of the G area in measures 29

through 31.

Example

2 shows the gradual submersion of the D collection and the reciprocal emergence

of the G collection. (18) The intervals of the ostinato

comprise the basic cell of the octatonic collection [013], and it is therefore

not surprising that octatonicism plays an integrative role in the prelude,

where it aids the transformation of the D into the G (19)

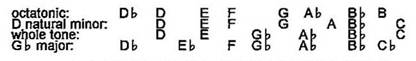

Figure 1: Overlapping sets in "Des pas sur la neige"

An

additional aspect of organization in the prelude, one that enhances the

ambiguity of the pitch collections, is the reordering of repeated material.

This technique plays a similar role in Wolpe's Form for Piano, as shown in Martin Brody's

"Sensibility Defined: Set Projection in Stefan Wolpe's Form for piano" (20),

where Brody describes the migration of what Wolpe calls "autonomous

fragments." Although these fragments are sometimes no larger than a single

interval, their irregular patterns of repetition have a mnemonic function

similar to reordered measures in Debussy.

Mm. 3 and 19 in "Des pas sur la

neige" are nearly identical, and mm. 5 and 20 are completely so. But the

logic of source measures 3 to 5 is broken by the omission of the intermediary

m. 4: there is no duplicate m. 4 separating m. 19 from m. 20. Such telescoping

makes it difficult to recall the original order of materials. This stands in

stark contrast to conventional tonal forms, which depend on strict succession and

literal repetition to support recollection and comparison. The technique of

fugitive retrospection in "Des pas sur la neige" is suggestive of the

Symbolist aesthetic of transcendence that sought trans-temporal

"recollections" of prior existences throughout painting and poetry.

Dialectical

form pervades 20th century music. Elliott Carter speaks of his own 'epiphanic

form' and articulates a lineage with Debussy and Schoenberg. In Carter's

'epiphanic form,'

...

the relations between musical ideas are revealed non-linearly across a piece

rather than in the

form

of theme and variation or development. The term 'epiphany' was adopted by James

Joyce

to

mean the sudden revelation of meaning; ... Carter points to Schoenberg's Erwartung and to

Debussy's

Jeux as musical

precedents for this technique. (21)

Carter might have added Stravinsky to his

list; examples abound: Symphonies

of Wind Instruments (1920, rev. 1947) is a case in point. It originated

as a chorale for piano in memory of Debussy. Stravinsky made the chorale serve

as the conclusion to the wind piece and composed the rest of the work to lead

up to it. The chorale is foreshadowed a number of times before its emergence.

A dialectic of emergence is at work in much

of Schoenberg's music. The Serenade

op. 24 - a direct predecessor of 12-tone composition - is a case in point. The

motif of the parodistic first section of the Tanzscene

movement is a hexachord whose symmetrical complement is the thematic basis of

the movement's more lyrical trio sections. (22)

Hexachordal opposition produces a polarity in the fabric of the work.

Schoenberg was to make use of this polarity - to a greater or lesser degree -

in all subsequent hexachordal compositions. Here, the emergent moment is

replaced by an oscillation between complementary hexachords. Wolpe extended

this idea to include an oscillation between two unequal or asymmetrical pitch

collections, as in the second movement of Piece

in Two Parts for flute and piano and Form for piano.

Stefan Wolpe's long friendship with

Varèse reinforced his early predilection for dialectical thinking. Many

of Wolpe's works - particularly the late music - must be understood in this

perspective. (23) Both Wolpe and Varèse posited a musical

space that acts as a field for pitch structure. (24)

Varèse's works (and Wolpe's from Form

for piano and after) are made up of assemblings and dispersals of pitch

symmetries that underlie and motivate such structures, generating a total form

that Varèse describes as analogous to the growth of crystals. (25)

Here, the dialectical opposition is a series of contradictions, the totality of

which is the form of the work.

Austin Clarkson, speaking of Wolpe's notion

of fantasy, quotes Karl Jung's distinction between 'symbol' and 'sign', where a

sign stands for a "known thing" while a symbol "formulates an

essential unconscious factor." (26) Wolpe

not only drew upon Debussy's formal innovations, but also, surprisingly, his

art of fashioning symbol-laden musical ideas as well.

Clarkson describes Form for piano as a series

of "forty or so images." He goes on to say that

The

forces needed to make so many different items cohere are generated not from

familiar

rhetorical strategies of exposition, complication, crisis, and release, but from

the ten-

sions

generated from the juxtaposition of strongly contrasted images. (27)

Wolpe suggests this in

his notes to Form

for piano, as well as verifying its dialectical basis, when he writes:

Since

opposites become adjacencies, the modes of opposite expression as hard and

soft, wild

and

tame, flowing and hesitant, etc., all these modes become self-inclusive. The

piece feeds its

own

totality and brings everything into its focus. (28)

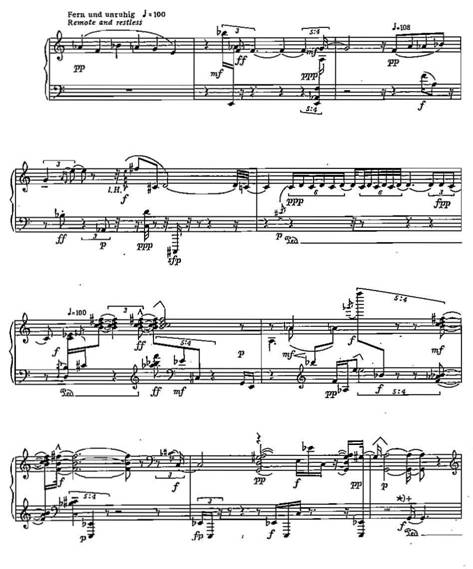

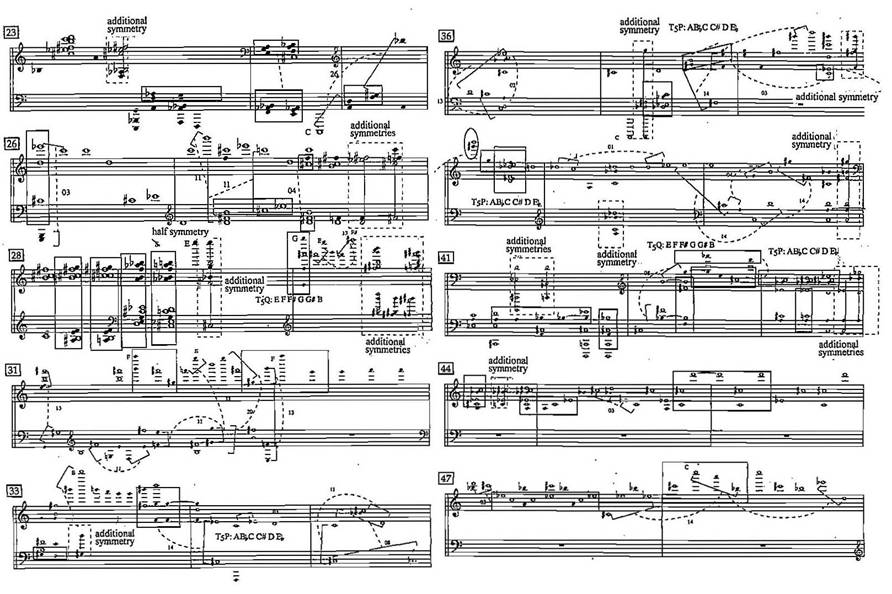

The

"thesis" of Wolpe's Form

for piano is self-evident; it is the hexachordal monody that begins the piece

(see Example 3). Its antithesis is the complementary hexachord in m. 4. The

dialectical unfolding and interpenetration of these two hexachords eventually

generates their

transpositions, which emerge at just before the midpoint of the piece at m. 30

and then dominate it until m. 58, as shown in Figure 2. The emergence of the

transpositions is the dialectical core of the work.

I shall borrow Brody's nomenclature and call

hexachord I, "P"; its transposition is T5P. Hexachord II is called Q

and its transposition is T5Q. In Figure 2 P is indicated with black noteheads

and Q with white. Transpositions are indicated with small noteheads. This makes

clear the interpenetration of the hexachords and the emergence of the

transpositions. Pushing Debussy's principle of non-repetition even farther, no

measures - or even symmetries - are repeated literally.

Although P and Q are equally well-represented

in Form, P is

granted special status; it makes up the opening monody and its two successive

variants, and is repeated just before the end in MM. 59 to 61; an octave lower

and with varied attack patterns, but still recognizable as a thematic idea. Q,

however, functions as the "Other"; the antithetical content into

which P continually dissolves. Clarkson, paraphrasing Wolpe, describes each

hexachord with a compound image: the first as "inward, centering,

compressing, and contracting" while the second "expands, rarifies,

unfocuses, and releases."

Two

principles govern the structure of Form.

The first is the interpenetration of hexachords; the second is the disposition

of symmetrical relations between them. Where these groups appear alone there

tend to be fewer symmetries and very little polyphony (as in MM. 1-3, 5,

the first half of 6, 11-12 or 60-64.) When they interpenetrate, a web of

symmetries appears, often spanning the entire range of the passage from the

highest to the lowest pitch, as in MM. 28 and 51.

Example 3 :

Wolpe Form, opening page

© Tonos Editions, distr. Seesaw Music 2067 Broadway

Ave, NYC

Figure 2: Wolpe: Form, Hexachodal Analysis:

Boxes and brackets mark symmetries. Dotted boxes show dotted symmetries.

Intervals of symmetry is sometimes indicated for clarity. Whlte noteheads:

Hexachord P. Black noteheads: Hexachord Q. Small noteheads: transpositions.

These

symmetrical progressions are dynamic; they result from the projection of intervals

from register to register. Such interval likenesses create the spatial

dimensionality so characteristic of Wolpe's music. The projected intervals

operate in the manner of rhymes which link together dissimilar ideas and

project a poem forward in time. Figure 2 shows symmetries as boxed pitch groups

or as bracketed pitches connected by dotted lines. Dotted boxes show additional

symmetries. Hexachord mixtures tend to present the greatest symmetrical

content, as in mm. 14-15, 27, and particularly 28.

The interaction

of symmetries is the dialectic of Form

for piano. As Example 3 shows, there is very little music that escapes these

symmetrical relationships, which must have been sketched out first in what

Wolpe called "precompositional selectivity." Pitches that do not

sound in vertical symmetries are nearly always part of a horizontal symmetry,

as the G and A in m. 4, which, together with the E F#, are in symmetrical

opposition to the D C in the same measure. More than simply reiterating an

interval, the G and A from hexachord P are projected onto kindred intervals in

the suddenly emerging hexachord Q in dialectical forward motion.

There are

four basic dialectical tropes in Form::

Emergence:

of hexachord T5P and T5Q

Interpenetration:

here, the hexachordal process

Transformation:

the recomposition of hexachords, as in the reworkings of P in mm.1-4

Symmetry

As we

have seen, the first three are also characteristic of "Des pas sur la

neige". It is here that that the kinship between Wolpe and Debussy visibly

emerges. While symmetry plays no obvious role in Debussy, it is worth noting

that the whole tone, octatonic and pentatonic collections are symmetrical, as

are many of their subsets, and this colors the pitch language of "Des pas

sur la neige". The above categories are not meant to be exhaustive - many

others are possible - but are offered as a first step in the creation of a new

analytic instrument.

The

notion of dialectical form permits us to think about post-tonal music in an

active mode. Viewed from this perspective, each event in a work so constructed

bears a meaningful and dynamic relationship to the process of emergence that

governs it, rather than simply manifesting a series of "one thing after

another" that Wolpe parodies in "Thinking Twice" (29) and

often dismissed as a "mittler Zustand Extase" (average-state

ecstasy).

Wolpe

delighted in teaching "Des pas sur la neige". It must be admitted

that no Wolpe sound surface resembles it, Form

for piano least of all. That composers as dissimilar as Wolpe and Debussy could

have shared a common understanding of musical form- as well as a kinship

relation as far as musical imagery is concerned - is evidence of a broader

historical process that embraced them both.

1. There are also extended types of

dialectical form: a rondo-like succession of syntheses (as in the emergent

moments of Debussy's "La Cathedrale engloutie"; or a continuous

series of momentary syntheses, as in works of Edgard Varèse and Stefan

Wolpe. See Greenbaum, "The Proportions of Density 21.5: Wolpean Symmetries

in the Music of Edgard Varèse" in On the Music of

Stefan Wolpe,

Austin Clarkson, ed., Pendragon (Hillsdale, New York: 2003) 207-219.

2.

David

B. Dennis, "Beethoven at large: reception in literature, the arts,

philosophy, and politics" in The

Cambridge Companion to Beethoven, Glenn Stanley, ed., Cambridge U

Press (Cambridge: 2000) 300. Beethoven's motivic unity over multiple-movement

compositions, as well as his use of cyclical forms, are suggestive of

dialectical thinking.

3.

The

Frankfort School post-Hegelian Theodor Adorno understood the Beethoven's

late-period style as a dialectic between the subjective and objective which

embodied a fatalistic reaction to the failure of political ideals. More to the

point, he understood exposition/development/ recapitulation in Beethoven's

middle period style as embodying the thesis/antithesis and integration of the

dialectic. See Rose Rosengard Subotnik, "Adorno's Diagnosis of Beethoven's

Late Style: Early Symptoms of a Fatal Condition," JAMS 29, 1976 242-275. A

rather simplistic dialectical-materialist approach to Beethoven and Hegel can

be found in Ballantine C., "Beethoven, Hegel and Marx" in Music Review 33, 1972, pp.

34-7.

Philip T.

Barford ("Beethoven and Hegel," Musica

1953, 437-440) has pointed out that the tension between

subjectivity and objectivity in Beethoven's sonata forms is precisely that of

Hegel's understanding of music in the Aesthetik.

4.

The

Art of Rhetoric,

trans. H. C. Lawson-Tancred. Penguin (London: 1991) 68.

5.

Hans

Lenneberg, "Johann Mattheson on Affect and Rhetoric in Music (II)," Journal of Music Theory

119-236. 195.

6.

Hans

Lenneberg, "Johann Mattheson on Affect and Rhetoric in Music (II)," Journal of Music Theory

119-236. 195.

7.

Riepel,

Anfangsgründe zur musikalischen Setzkunst 1752; quoted in Mark Evan Bonds,

Wordless Rhetoric: Musical

Form and the Metaphor of the Oration Harvard University Press

(Cambridge and London: 1991) 99.

8.

Bonds

124.

9.

E.g.,

" ... such progressions and modulations ... which require none too violent

antitheses [Gegensätzen]

... Rather, a satisfactory unity [Einheit] is produced." Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel,

Vorlesungen über die Äesthetik III: Works: 15. Surhrkamp

(Frankfurt am Main: 1970) Hegel 187.

10.

Hegel

188-189.

11.

Hegel

217.

12.

"Correspondances

[in Les Fleurs du Mal]

... became the gospel of the new poetic movement. The language of Baudelaire

appeals as much to the intellect of the reader as to his physical

sensibilities. It does not directly represent things and feelings; it offers a

choice of the most suggestive correspondences among analogies which exist

between words, and sounds and their atmosphere-a choice which tends to create a

harmonious poetic substance which acts upon the imagination, not only through

its meaning, but also through its sound." Stefan Jarocinski, Debussy:

Impressionism and Symbolism, Rollo Myers trans. Eulenberg Books (London: 1976)

65.

13.

Wagner

speaks of Hegel only in connection with his metaphysics; Hegel was replaced,

first by Feuerbach and then Schopenhauer, in his philosophical development. See

Bryan Magee, The Tristan

Chord, Metropolitan Books (NY: 2000) 134 and passim.

14.

It

is no longer "confined to reproducing, more or less exactly, Nature, but

the mysterious correspondences which link Nature with

Imagination."Jarocinski 96.

15.

An

attempt to diagram its form as AB A/B (A/B = combination) appears in Richard S.

Parks, The Music of Claude

Debussy. Yale University Press (New Haven and London 1989) 222. Parks

writes, "Another ternary-derived archetype is the tripartite design ...

whose last section synthesizes characteristic features of the first two."

The above AB A/B schema obscures an essential quality of dialectical form: the

progressive generation of B from A and their interaction, so that B gradually

and organically emerges as the antithesis of A.

16.

See

also "Voiles" (Préludes

I #2), where a

whole-tone collection cedes to the emergence of a pentatonic collection).

17.

Pitch-class

E is a member of the whole-tone collection, pitch-class F is a member of the G

major collection, and pitch-class D is shared by both. The figure is meant to

have the sonic value of a sad and frozen landscape: "Ce rhythme doit avoir

la valeur sonore d'un fond du paysage triste et glacé."

18.

In

Example 2 the D minor collection is marked by diamond-shaped noteheads, the

octatonic collection by dotted rectangles and the whole-tone collection by

circles. The G collection is shown in conventional noteheads. Pitch-classes F

and B are shared between the D minor and G collections,

but are not

indicated as such in Figure 1so as to make the emergent processes clearer.

19.

Chromaticism

also plays a constructive role. A half-step source is immediately established

in the ostinato's E F. The half-step idea is further extended in measure 8 and

the near-duplicate 9, accompanied by parallel chromatic minor sevenths B/C to

B/C# in half notes. These are in turn connected by the chromatic trichord F# G

G# in quarter-note motion. Measure 10 - an altered repetition of measure 8 -

presents a chromatic trichord in contrary motion BA A. All this produces an

eleven-member chro-matic set A A B C# D E F F# G G# . The aggregate is

completed by the prelude's first E, in measure 12. (The trichord connection

reappears as C B B in measure 15.) The chromatic process continues in measures

23 to 24. Here, a tetrachord D D E E supports a series of altered dominants.

This leads to a culmination of the chromatic process at measure 26 to 27 where

the trichord G G F supports a series of minor triads as well as a tetrachord D

D C B. These triads, along with the accompanying ostinato form the 11-member

collection E F G G G# A B B C D D. Again, the missing pitch is E, which had

just been heard in the bass motion in measure 24.

20.

Perspectives

of New Music

Spring-Summer 1977.

21.

The

Music of Elliott Carter, David Schiff, Cornell University Press (Ithaca: 1998)

39-40.

22.

George

Perle, Serial Composition

and Atonality. Fourth Edition (U Cal Press: 1977) 94-5.

23.

Greenbaum,

"Stefan Wolpe's Dialectical Logic."

24.

Varèse

- the revolutionary sound surface of his works notwithstanding - was profoundly

influenced by Debussy; this influence is manifest in his brief Un grand sommeil noir

(1906).

25.

Matthew

Greenbaum, "The Proportions of Density 21.5."

26.

"'The

Fantasy Can be Critically Examined': Composition and theory in the thought of

Stefan Wolpe," in Music

Theory and the Exploration of the Past, D. Bernstein & C. Hatch

eds., (U Chicago 1993), 505-524.

27.

Clarkson

507.

28.

Clarkson

520.

29.

in

Elliott Schwartz and Barney Childs, eds., Contemporary

Composers on Contemporary Music (New York, 1967) 274.