Dialectic in Miniature:

Arnold Schoenberg’s Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke Opus 19

Matthew

Greenbaum

If one were to ask, “is there a

principle of contrast in Schoenberg’s music?” the answer, while always affirmative,

would vary, depending on where a particular work fell in the chronology of his

compositions. While the 12-tone works demand a certain set of answers to this

question, Schoenberg’s transitional works - those that precede the twelve-tone

system and follow the more-or-less tonal works - offer varied examples of

dialectical processes.[1]

The collection of miniatures, the Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke Opus 19, is

an interwoven fabric of tonal artifacts and there are distinctions between the

horizontal and vertical aspects that reveal a subtle connection to the tonal

universe. What these aspects have in

common is a high degree of symmetry. In the conflict between these aspects lies

the dialectical process that governs the work as a whole and the six pieces

individually.

The musical concentration of these

pieces - combined with their brevity -creates a highly ambiguous musical

language that defies conclusive analysis. Indeed, it is one of the attractions

of Opus 19 that the longer one studies it, the more heterodox it seems.

The concept of symmetry as an

organizing structural principle was not Schoenberg’s invention. Toward the end

of the 19th century the idea of the tonal center became entwined with notions

of inversional balance. The influential Hegelian music theorist, Moritz

Hauptmann, provoked a re-evaluation of musical structure when he analyzed the

tonic/subdominant relationship as an inversion of the tonic/dominant; David

Lewin links this to Schoenberg’s tonal and post tonal practice, illustrating

similar structures of inversion in the First

String Quartet and the cruciform symmetries of Pierrot Lunaire.[2]

The

symmetrical implications of Opus 19 have been studied by Jonathan Dunsby and

Arnold Whittall, who attempt to explain the second and sixth pieces as total

symmetries, akin to the first movement of Anton Webern’s Symphony Opus 21. This requires a certain amount of manipulation;

Dunsby and Whittall sometimes fill in incomplete symmetries with pitches that

appear later in the pieces and certain octave displacements are necessary.[4] Although their Example 29, an analysis of the

second piece of Opus 19, shows tightly packed chromatic regions toward the

center and relatively larger intervals at the extremes, similar results might

well be attained from many chromatic pieces, given the general tendency toward

larger intervals in the lower registers, and saturation of those intervals

within the treble and bass staves.

Even within the confines of tonal

music Schoenberg recognized a motivic kinship between like intervals (i.e.,

symmetries) in musical development. In Fundamentals

of Musical Composition he writes: “Every element or feature of a motive or

phrase must be considered to be a motive if it is treated as such, i.e., if it

is repeated with or without variation;” [6]

he also notes that dyads can be motivic details, or any “pitch succession or

duration succession of two or three members …”[7]

This is significant when one considers the multitude of dyadic symmetries in

Opus 19.

In Opus 19

the interval sound - its Klang - is

tied up with replication of like intervals. Focus on the actual sound of a

pitch rather than its relative meaning within a tonal structure was a decisive

step in Schoenberg’s musical evolution.

The often-noted 05s (perfect fourths) in the opening of the Kammersinfonie Opus 9 are a familiar

example, and perfect fourths play an important structural role in Opus 19 as

well.[10]

Indeed the Kammersinfonie opening

foreshadows a texture completely dominated by this one interval (end of measure

360 to 368; end of 371 to first half of 373). Such a concentration on a single

interval is probably the first appearance of such an idea in the history of

music.[11]

The whole-tone content of the first theme of the Kammersinfonie is similarly composed out (Schoenberg was proud of

the work’s integration of themes and harmonies).[12] By Opus 19 the interval was liberated and was

projected into the free musical space of which Edgard Varèse and Stefan Wolpe

would later speak.[13]

The

differentiated function of steps and skips in Opus 19 is a relic of tonality.

From the perspective of Schoenberg’s twelve-tone works, which banished the

distinction between the horizontal and vertical, it seems out of character to

find just such a distinction in Schoenberg’s earlier music. And yet, verticals

are manifested in Opus 19 by specific intervals deployed in symmetrical

configurations: in the entire six pieces there are no simultaneous pairs of adjacent half steps or whole steps - or pairs

of adjacent half-steps and adjacent whole-steps; these interval combinations

are always expressed horizontally.

Adjacent half

steps often act as connectors between symmetrical events, recalling similar

moments in Debussy’s Des pas sur la neige.[14] The dialectic between the vertical skip

and the horizontal step, long present in Western music - where ”Pythagorean”

perfect intervals oppose the melodic line and its dissonances - is still

faintly present in Opus 19. One can think of symmetrical simultaneities as

points of relative stasis and of steps as destabilizing transitions. Melodic

shapes - particularly in I, III, IV and V - can be heard as surface

manifestations of the interplay of symmetries.[15]

The following

analysis is based on an Occam’s razor approach; it considers only two elements:

like-interval sets (3/3, 4/4, 5/5, etc.) and horizontal symmetries. While

possessing no specific tonal function in the work, like-interval sets appear

throughout, sometimes alone and often interpenetrating. Horizontal symmetries, in contrast, form

connective links between these cells.

The 3/3/3, “diminished seventh,” and 4/4, the

“augmented triad” cells, have a special property not shared by sets other than

the total chromatic: they are infinitely repeating (i.e., C E![]() F# A/C E

F# A/C E![]() ……/C E G# C E …..). Besides its

philosophical suggestiveness, this property helps to form the specific Klang of the work; these subsets are

more “redundant” than other subsets: their registral displacement merely

produces more of the same pitches, forming a subtle timbral backdrop less

determined by registral distinctions than the asymmetrical elements that create

the specific environment of tonal music. The frequent 5/5 details imply a

fourth cycle which would require 11 iterations to return to its initial pitch

class, like the chromatic scale. However, it is still an infinite series, and

to the extent that it plays a role in the piece (particularly in pieces I and

VI) it also suggests boundlessness; indeed, the quartal, ic5 collection, which

fully emerges only in the last movement, is prepared from the first measure of

the work, as will be discussed in relation to piece VI.

……/C E G# C E …..). Besides its

philosophical suggestiveness, this property helps to form the specific Klang of the work; these subsets are

more “redundant” than other subsets: their registral displacement merely

produces more of the same pitches, forming a subtle timbral backdrop less

determined by registral distinctions than the asymmetrical elements that create

the specific environment of tonal music. The frequent 5/5 details imply a

fourth cycle which would require 11 iterations to return to its initial pitch

class, like the chromatic scale. However, it is still an infinite series, and

to the extent that it plays a role in the piece (particularly in pieces I and

VI) it also suggests boundlessness; indeed, the quartal, ic5 collection, which

fully emerges only in the last movement, is prepared from the first measure of

the work, as will be discussed in relation to piece VI.

Every pitch

in Opus 19 can be understood as a member of at least one symmetry, although

nearly all pitches are members of at least two. Besides the like-interval cells

and linear symmetries, there are contour symmetries and convergence symmetries,

which will be discussed below.[16]

A special chart is devoted to the emergence of ic5 symmetry over the course of

the pieces.

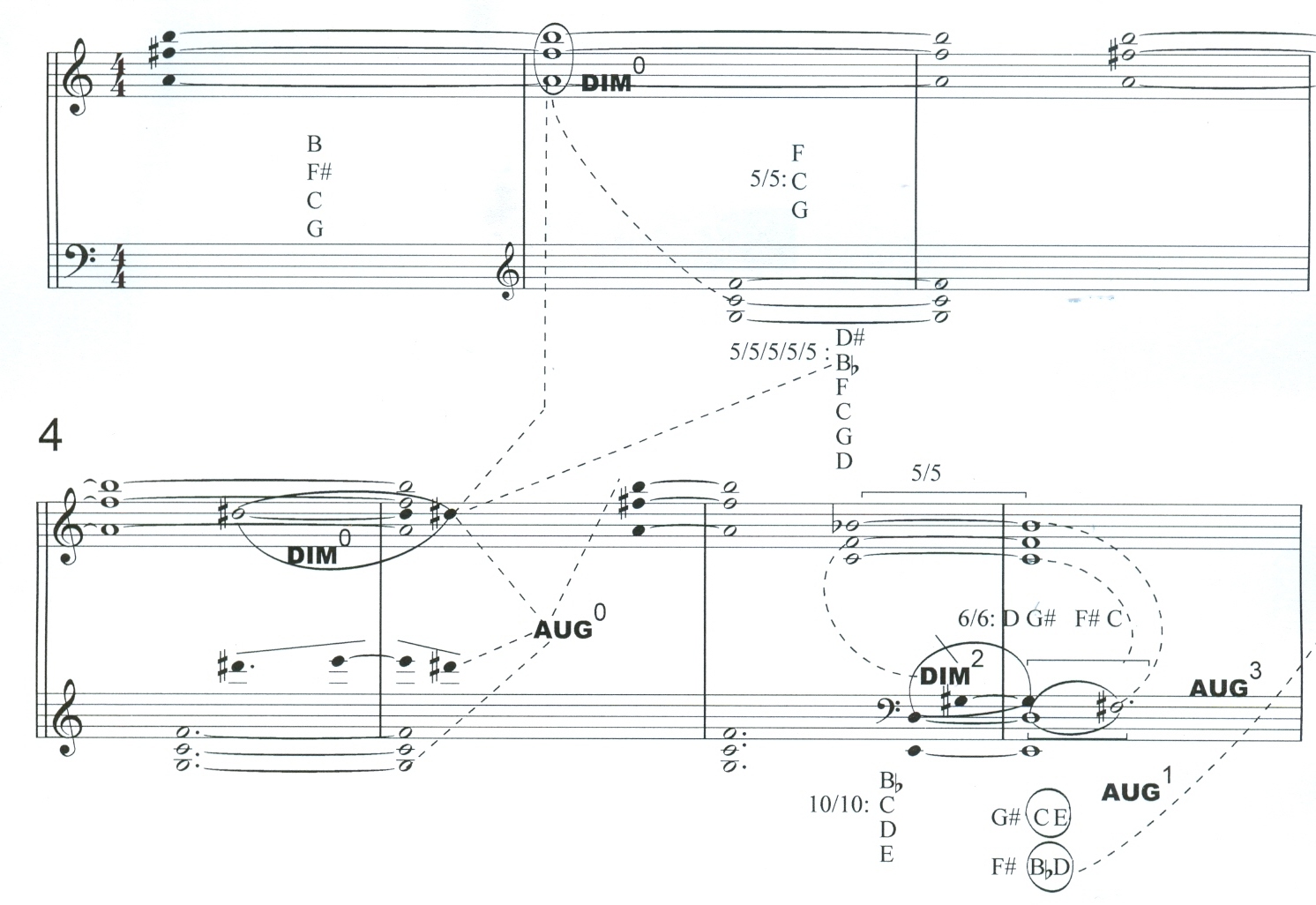

In the

following analyses, the four possible augmented triads are indicated as AUG0, 1, 2, 3 (G B D# = AUG0 as in measure 1 of I, see Example

1 below). The three diminished seventh

chords are identified as DIM0, 1, 2,

where DIM0 =A C D# F#. Diminished

triads are included in the DIM forms

to which they belong. Other symmetries are bracketed and expressed as interval

pairs, with additional interval projections indicated as well. AUGs and DIMs in which a symmetry is disturbed by registral displacement are

indicated with a slash line through the circle indicating the symmetry.

Consecutive

symmetries in Opus 19 often share a common tone.[17]

Their combination and linkage determine the narrative of each piece. To

whatever degree the pitch-class content is subset-related, these relationships

are of a lower order of structural importance than registral symmetries.

Schoenberg, in the radio address

quoted above, notes that “a minor third can become a major third.” If the remark has any meaning - and I think it is very significant - it must

refer to such events as the opening right hand collection in the first piece B

D# F F#, compared to the subsequent B![]() A F# D#

in measure 2. Or, in measure 3 the converging figure B E A G G# (-7 +5 -2 +1).[18]

Since the pieces are composed of ic3 and ic4 compounds, the entirety of the

work can be heard as a play of expansion and contraction, signaled on the

larger scale by convergent figures such as the one in measure 3.

A F# D#

in measure 2. Or, in measure 3 the converging figure B E A G G# (-7 +5 -2 +1).[18]

Since the pieces are composed of ic3 and ic4 compounds, the entirety of the

work can be heard as a play of expansion and contraction, signaled on the

larger scale by convergent figures such as the one in measure 3.

Scalar

Motion

Series of whole

and half steps form connections between harmonic events throughout the

opus. In piece I, the chromatic descent

from the F in measure 4 down to the A at the end of measure 5 foreshadows the

major third descent at the end of piece

II, the linear ascent and descent in piece III, measures 1 to 4 (lh), and the

stepwise ascent in IV, measures 4 to

6 and 7-8. Note that the chromatic descent in I is also clearly referenced in

IV, measures 2-3; both begin with an F in the same register:

I: F (G![]() ) E E-flat D D

) E E-flat D D![]() C

B B

C

B B![]() A

A

IV: F

E D# D (C# preceding F) C A# B

Figure 1:

Comparison of Scalar Motions in Piece I, m. 4 and IV m. 2-3 in Op. 19

Linear Symmetries

Symmetrical step-wise motion permeates Opus

19. Note, for example, in I m. 6 - 7 (lh) the dyad pair D E![]() /B

/B![]() A (+1 -1). It connects the AUG2 in measure 6 with the DIM2 in measure 7, or the -5/+5

symmetry between measures 16 and 17 (lh). This ic5 cell recalls the D

A (+1 -1). It connects the AUG2 in measure 6 with the DIM2 in measure 7, or the -5/+5

symmetry between measures 16 and 17 (lh). This ic5 cell recalls the D![]() and F# in measure 2, where they occur in the same register:

and F# in measure 2, where they occur in the same register:

Measure

2: rh

A B![]() / lh F

E D

/ lh F

E D![]() B

B![]()

Measures

16-17: lh B![]() A E (rh)

F# C# F

A E (rh)

F# C# F

Figure 2:

Comparison of Scalar Motions in I, m. 4 and I. m. 4-6, 7-8 of Op. 19

Convergence

Convergent motion

- a pattern of decreasing interval sizes - is a most interesting surface detail

in Opus 19; it is essentially highly developed contrary motion and often in the

form of a compound melody. It occurs a number of times in I (see Example 1 below): the first across

measures 2 and 3, fills in a minor third, the second is in measure 3 and can be

understood either as a strand of shrinking interval sizes or as contrary motion

by steps (B-A-A / E-G-G#). A third, in

measure 7, is very close to conventional voice leading, and the convergence in

measure 13 (lh) answers measure 7 and extends into the next measure. The very

significant convergence at measure 11 is echoed in another prominent

convergence in V, measures 1 to 3. The cadence point - F# D# E - is common to

both figures. Secondly, the passages

share the same pitches:

I measure 11 rh: D![]() /B

/B![]() F G

F G![]() (C#) F# D# E

(C#) F# D# E

V

measure 1 lh: D![]() F G

F G![]() (B

(B![]() ) rh: F# D# E

) rh: F# D# E

C.f.

III m. 7: D# E

Figure 3:

Comparison of Convergent Motions in I, m. 11 and V m. 1, of Op. 19

Finally,

as we shall see, convergence in the final measure of I is of crucial importance

in the unity of the work.

Contour

Symmetries

Contour

symmetries, i.e., brief arch-forms, are ubiquitous in the six pieces (indicated

by V-shaped lines). These brief oscillatory moments are a bit nostalgic -

similar shapes might occur in Schumann - but they also reinforce the

thoroughgoing symmetrical structure of the work. While contour symmetries occur

earlier in the first piece - e.g., measure 2 A B![]() A - the most prominent is the concluding gesture, which foreshadows events in

subsequent movements and signals closure in the first piece. The uppermost

contour symmetry D# E D# is a very significant foreshadowing of the last piece.

A - the most prominent is the concluding gesture, which foreshadows events in

subsequent movements and signals closure in the first piece. The uppermost

contour symmetry D# E D# is a very significant foreshadowing of the last piece.

Opus

19, I

The first

piece in the Opus 19 collection is very suggestive of a prelude: it is the

longest of the pieces and most varied in texture. The arpeggiations in the first

three measures signal its prelude quality, while the melodic arc of the first

two measures is a model for both the conclusion of the movement and for similar

melodic shapes in the others.[19]

The

sudden intricacy of measures 4-6 is governed by a descending chromatic line

(discussed below), supported by a series of AUG and DIM cells and

concluding with the contrapuntal

measure 6. A second melodic arc can be

traced in the left hand of measure 6,

passing to the

right hand A in

measure 9, then t o the

G in measure 10, and finally converging on the E in measure

12. This shape encapsulates the movement’s emergent moment - the

tremolo/sustained figure in measures 8-12 - and connects it with the

contrapuntal music. Two further melodic arcs (13-14, 15-end) close the

movement, in a gently lingering decay anticipating the conclusion of the entire

set.

![]()

Example 1: Schoenberg,

Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke, I

All

transpositions of the third-cells are exposed by measure 5, which concludes

with an unadorned first statement of AUG3,

a cell that also occurs in the last measure. AUG0 has cadential implications in three of the other pieces as

well:

First Measures Last Measure

I AUG0 AUG0

I AUG0 AUG0

III AUG0 AUG0

IV

AUG0

(penultimate measure)

Figure 4: Use of

Opening and Closing AUG0 Collections

in Op. 19

In addition,

nearly every pairing of third-cells in the entire set first appears in this

movement. As noted above, the DIM0

and AUG0 in measures 8 to 10 are

first paired in measure 1. These pairings - often, interweaving - create the

quicksilver harmonic interplay so characteristic of this movement.

The AUG0 tremolo/sustained figure in

measures 9 to 13 is the longest event in I, and its emergence is carefully

prepared in the opening measure where this trichord first occurs together with

the DIM0 collection (notes G and B

appear in the same registers in both places). The tremolo/sustained figure

decelerates the harmonic motion, but its bonding with the mercurial events

accompanying it assert the dialectic of vertical and horizontal symmetry.

Measure 2 of

I contains a brief but significant contrapuntal moment: the superimposed

imitation of B![]() A F# D# and F E D

A F# D# and F E D![]() B

B![]() .

Measures 4-6 present a dense web of contour- and inversional symmetries linked

with the chromatic thread running through the upper voices. Symmetries are

formalized by inversion in measures 5-6:

.

Measures 4-6 present a dense web of contour- and inversional symmetries linked

with the chromatic thread running through the upper voices. Symmetries are

formalized by inversion in measures 5-6:

measure

5-6: A![]() G B/D F#

F

G B/D F#

F

measure

6: D F# F/E D# G

Figure 5:

Contrapuntal Symmetries in mm. 5-6 o op.19, I

These

measures also contain less formally related cells, such as the A![]() A C# in the inner voice of measure 6 and the lowest voice F D E

A C# in the inner voice of measure 6 and the lowest voice F D E![]() ,

both comprised of thirds and half-steps.

,

both comprised of thirds and half-steps.

The form of

each piece is to a great degree determined by the location of its cells. AUG0 is of particular importance in

piece I and throughout the set, especially its pairing with DIM0, as in I mm. 1, 4 and 9. In measure 4, the pairing precedes the

semi-cadential AUG3; in measure 8

the pair makes up the “emergent moment.” In the final measure, a brief AUG0 is encapsulated in AUG3, which now forms a full cadence

(in phrasing rather than tonality), as opposed to its earlier half-cadence.

Opus

19, II

Opus 19 II is

a study of ic3 and ic4, placed in various symmetrical relationships with each

other and underpinned by broken linear patterns. There are no ic5s or ic7s in

the movement.[20]

The obsessive concentration on ic3 and ic4 is signaled by the B/G ostinato

figure that runs throughout. Following the diminished triad “half-cadence” in

m. 6, the conflict between major and minor thirds is resolved definitively in

the last measure in favor of ic4 with the superimposition of two augmented

triads.

In contrast

to the orderly situation of ic4s in specific registers, ic3s are rather “vagrant”

(to use Schoenberg’s anthropomorphism). The dyad D#/C, first occurring within

measure 3, appears an octave higher as an interpolation in the B/G ostinato. It

reappears as a simultaneity in its original register in measure 6 as one of a

pair of such repetitions, the other being C/A![]() ,

also in its original register. The reappearance of these dyads opposes the

third-types: a pair of ic4s (C/A

,

also in its original register. The reappearance of these dyads opposes the

third-types: a pair of ic4s (C/A![]() ,

C#/A) is succeeded by a pair of ic3s (E

,

C#/A) is succeeded by a pair of ic3s (E![]() /C,

D/B). The F#/D# ic3 between measures 2

and 3 appears an octave higher between the two augmented triads in the final

chord, encapsulating the interval in a dialectical end point.

/C,

D/B). The F#/D# ic3 between measures 2

and 3 appears an octave higher between the two augmented triads in the final

chord, encapsulating the interval in a dialectical end point.

Particularly

noteworthy is the “half cadence” of superimposed diminished triads at the end

of measure 6, and their “resolution” in the concluding superimposed augmented

triads.[21]

The diminished-triad verticality is an adumbration of a similar event in the

previous measure in which DIM0 and DIM1 are superimposed, with the G out of place.

The ostinato

B/G that runs through the movement is symmetrically completed by the E![]() B G triad in the final chord, and foreshadowed at measure 4. Similarly, the

upper triad of the final chord - D B

B G triad in the final chord, and foreshadowed at measure 4. Similarly, the

upper triad of the final chord - D B![]() F# - is foreshadowed by the B

F# - is foreshadowed by the B![]() /G

/G![]() in measure 5 and the high D in measure 2.

in measure 5 and the high D in measure 2.

The descending

line of whole steps (measures 7 to end) is unique in the opus, although echoed

in V, measures 8-10. Harder to parse is a first line of descending thirds from

measure 3 to measure 6. The ic3 A/C and ic4 C/A![]() dyads in measure lead to ic4 A# /F# in measure 5, followed in the next measure

by C/A

dyads in measure lead to ic4 A# /F# in measure 5, followed in the next measure

by C/A![]() (as in measure 3), C#/A and E

(as in measure 3), C#/A and E![]() /C

(rh) (ic4, ic4, ic3/ ic3), culminating in the D/B dyad in the “half-cadence.”

The strikingly literal descent of ic4s prefigures other more or less obvious

scalar passages throughout the opus.

/C

(rh) (ic4, ic4, ic3/ ic3), culminating in the D/B dyad in the “half-cadence.”

The strikingly literal descent of ic4s prefigures other more or less obvious

scalar passages throughout the opus.

The first

four measures of II may almost be thought of as a re-composition of measure 1

of I. Note that the G/B dyad retains its registral position (rh), as does the

F# in measure 2 and the E![]() in measure 4 (spelled D# in measure 1). Only the D in measure 2 of II, is absent in

the opening measure of the first piece. Indeed, the pair of AUG0 and DIM0 are featured in both. In its terseness and concentration,

piece II offers the greatest number of symmetrical relationships since every event

is intervallically mapped onto every other.

in measure 4 (spelled D# in measure 1). Only the D in measure 2 of II, is absent in

the opening measure of the first piece. Indeed, the pair of AUG0 and DIM0 are featured in both. In its terseness and concentration,

piece II offers the greatest number of symmetrical relationships since every event

is intervallically mapped onto every other.

Example 2: Schoenberg,

Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke, II

The third

piece contains the densest texture in the opus; yet it dwindles to a single

note - G - by measure 8. The dialectical process is a reductive one. A

thinning-out begins in measures 5 and 6, signaled by a converging symmetry in

the lower voices B![]() /C A/C# A

/C A/C# A![]() /

D. Note that the group B

/

D. Note that the group B![]() E

E![]() F A

F A![]() begins and ends the piece (c.f. pitches marked 1-4 in measures 1 and 9).

Closure is further asserted by the reversal of the descending B

begins and ends the piece (c.f. pitches marked 1-4 in measures 1 and 9).

Closure is further asserted by the reversal of the descending B![]() -E

-E![]() octaves in the first measure in a mirror echo in the last measure. In addition, the group of four pitches in

measure two - B

octaves in the first measure in a mirror echo in the last measure. In addition, the group of four pitches in

measure two - B![]() C D

C D![]() E

E![]() (numbered 5-8) - is partially retrograded in measures 3-4 (see pitches numbered

8, 6 and 5).

(numbered 5-8) - is partially retrograded in measures 3-4 (see pitches numbered

8, 6 and 5).

A long convergence of decreasing

interval size can be traced through the bass pitches in measures 1-3, (note

also the contrary voice leading in the rh in m.2) and is reflected further in

measure 4, before the convergence by contrary motion in measure 6 - B![]() A A

A A![]() (descending) / C C# D

(ascending) – thus encompassing virtually the entire movement (see Example 3).

(descending) / C C# D

(ascending) – thus encompassing virtually the entire movement (see Example 3).

Example 3: Schoenberg, Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke, III

The planar structure of the opening of piece

III is an unusual combination of opposing textures and dynamics, suggestive of

polytonality. The symmetries in the first four measures are manifested in the

bass in octaves and its distinctive scalar motion together with its engagement

with the upper voices. The upper voices in these measures are rich in

symmetrical motions involving thirds and fourths. Especially important to the

melodic shape of the opening is the symmetry between measures 1 and 2 (+3 -3:

C# E/ A F#).

The

importance of contour symmetries in Opus 19 is often reinforced by subtle

echoes between movements. For example,

the B D# B in measure 5 is anticipated in II, m.4 (B E![]() B); the little contour symmetry E

B); the little contour symmetry E![]() E D# in measure 7 is a registral displacement of pitches that conclude piece I

(upper voice) and which re-emerge prominently in VI.

E D# in measure 7 is a registral displacement of pitches that conclude piece I

(upper voice) and which re-emerge prominently in VI.

As in II,

important cadence points in III are determined by superimposed AUG and DIM cells. AUG0 and AUG2 form a half-cadence at measure 4, followed by DIM0 and DIM2 intertwined in measure 6

Densely

packed cells AUG0, DIM0, AUG2, DIM2 and AUG3 dominate III, nearly all of them

overlapping with the bass motion. AUG0

and DIM0 cells appear at the opening,

as they did in the previous two movements, and the AUG0 in measure 5 is a direct reference to the opening of both I

and II: the G/B dyad appears again, protrusively, in the same register as

measure 1 of I, and together with the D# revisits measure 4 of II. In III, m. 6, this continuity is reinforced

by the pairing of AUG0 and DIM2

- again, as in II, m. 6 - in

which pitches G, E![]() D

and A

D

and A![]() share registral identities with III, m. 6.

share registral identities with III, m. 6.

The premise

of this movement is the exposure and compression of a melodic line, supported

by occasional sharp chord-like punctuations.

The melody unfolds registrally in jagged skips through the opening, then

as smooth ascending lines in measures 4 to 6 and 7 to 9. A parallelism is maintained in the legato

responses to the angular opening in measures 2-3 and 7, where the C# E D#

figure is transposed to F# A G#.

The octave

displacement and temporal compression of measure 1 into the first beats of

measure 10 frames a similar relationship between measures 3-6 and 6-8. The

scalar D C F# G# A# B C (measures 3-6) - with all but F# and G# in a lower

octave – appears, also time-compressed in mm. 6-8. The initial D C in the

former group, after its fleeting grace-note reflection in m. 5, appears at the

end of the latter group, thus breaking up the whole-tone content of the pitch

collection.

IV is

primarily scalar, with references to scalar passages in other movements. The descending chromatic line in measures 2-5

(see Example 4) derives, as mentioned, from that of mm. 4-5 in the first piece

(see above). This derivation is reinforced by the appearance of the same AUG0 and AUG2 cells in measure 4, supporting a descending scale, just as

they do in I, m. 5. This is further

emphasized by the subtle reappearance of the 5/5 set (D) F G C in IV, m. 4,

which appears at the beginning of I and also comprises a major element of VI.

One of the most interesting structural details of

the piece is the shifting function of the A# B dyad that concludes the piece,

where it completes the linear F F# A# B symmetry and recalls the same tones in

identical registration within the unstable and interweaving melodic line

of mm. 7-8.

Example 4: Schoenberg,

Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke, IV

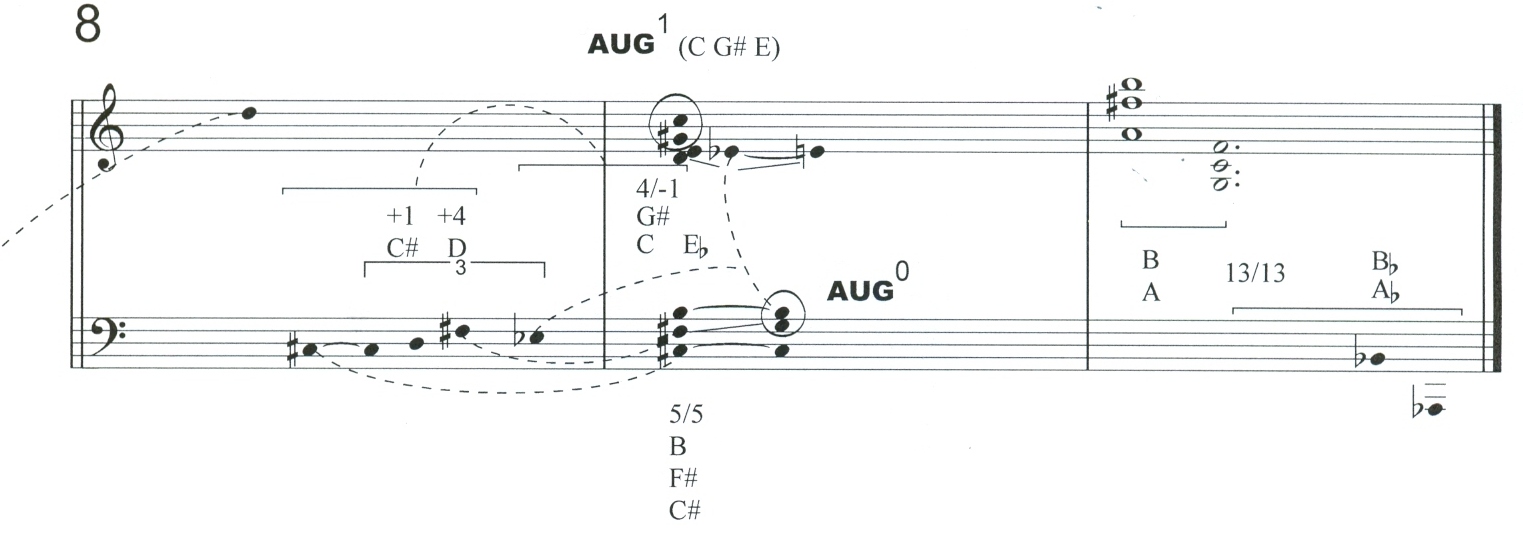

Opus

19, V

The fifth

piece - more or less a waltz - is based on accumulation of intervals. The

increasing density of the thirds - inner voices in measure 1 to pairs of thirds

in all voices at the end - suggest that the dialectical structure of the fifth

piece is in the transformation of single intervals into a texture composed of

these intervals, recalling the saturation of ic5s in the Kammersinfonie (i.e., transformation of quantity into quality).

The opening measure

is characteristic Schoenberg; the contrary motion between the hands encloses an

inversional relation between two diminished triads: C A G![]() (rh) and B D F (lh), offset by a sixteenth note. This is echoed in measure 2 in

a linear inversion between the left hand (G A

(rh) and B D F (lh), offset by a sixteenth note. This is echoed in measure 2 in

a linear inversion between the left hand (G A![]() B

B![]() )

and the right (A G# F#), the latter in augmentation and echoing the descending

contour of I, m.2 (B

)

and the right (A G# F#), the latter in augmentation and echoing the descending

contour of I, m.2 (B![]() A F# D#). The right-hand convergence in the opening two measures is paired with

another in contrary motion in the left hand (see Example 5) and in m. 4, IV

also recalls the polyphonic texture of I, m. 6 although with more structured

organization of trichordal retrogrades and inversions.

A F# D#). The right-hand convergence in the opening two measures is paired with

another in contrary motion in the left hand (see Example 5) and in m. 4, IV

also recalls the polyphonic texture of I, m. 6 although with more structured

organization of trichordal retrogrades and inversions.

The fifth

piece is particularly referential. The AUG2

and DIM0 in the opening two measures

is a reinterpretation of the first three measures of IV: F C and B![]() are registrally invariant, and pitches D

are registrally invariant, and pitches D![]() B (bass clef) and A are reiterated. Also

note the quasi-tonal transposition of

the B

B (bass clef) and A are reiterated. Also

note the quasi-tonal transposition of

the B![]() D

D![]() C A figure (IV, mm. 1-3) to G

C A figure (IV, mm. 1-3) to G![]() B

B![]() A (V, opening) within a pseudo-F-major context.

A (V, opening) within a pseudo-F-major context.

Three

occurrences of AUG0 (measures 8, 9

and 12) are part of a network of references that spans all of I, II, III, IV

and VI. In particular, its occurrence in

measure 12 is in the same registration as that of the opening of the work (I,

m.1). The interesting superimposition of AUG1

and AUG2 at the conclusion, in which

one pitch in each is shifted to the other, recalls the conclusion of II and its

superimposed AUG0 and AUG3. Note the identical interval of separation

(ic1) for both pairs and the reversal in the lower left hand of the voice

leading of the exposed E![]() -D

of m.11.

-D

of m.11.

The contour symmetry in measures 7-8 recalls I, m.

3, in its shape if not in its pitch content, and the series of descending ic4s

in the left hand in measures 9-10 - as blatant as any of the internal

references in the work - clearly suggests the descending ic4s at the end of II.

The half-step motion of the contour symmetry also predicts the descending ic4

pairs in measures 9-10, which in turn anticipate the cadence. Pairs of thirds

also connect V and II:

II V

measure

5 measure 9

G

B/F# A# G B/F# A#

measure

6 measure 10

A![]() C/A C# B

C/A C# B![]() D/A C#

(inversion)

D/A C#

(inversion)

measure

5 measure 12

G

B/F# A# G B/G![]() B

B![]()

measure

6 measure 14-15

A![]() C/A C# rh A

C/A C# rh A![]() C/A C#

C/A C#

measure

7 measure 14-15

F

A lh F A/E

G#

Figure 6:

Schoenberg Comparison of Third Pairings in Op. 19, II and V

Example 5: Schoenberg,

Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke, V

Op.

19, VI

A tolling figure runs through the brief final

movement, which Schoenberg composed after hearing of Mahler’s death. It owes its retrospective and pensive

character not only to the sound quality of the tolling intervals, but also

because of strands of reference to previous movements. In fact, there is very

little in the movement that cannot be found in earlier ones.

Tones B and A in the upper half of

the tolling figure are the initial notes of the entire piece; the F# occurs at

the end of measure 1. (Note that the three pitches appear an octave higher in

VI, but in the same 6/9 registral relation to each other.) The other element of

the tolling figure - F C G - appears in I, m, 1 as well, and in the same

register. In VI the DIM0 in measures

4-5 linking the two halves supports an important long-range connection between

the first and last movements.

The DIM0 in measures 4-5 is accompanied - unusually - by a D# in

octaves. The upper note is part of the

contour symmetry D# E D#, which first occurs in the last measure of I (upper

voice, with adjacent D# octave). This detail is also one of the most telling

and poignant recollections in the set of pieces (also see III, m. 7: E![]() E E

E E![]() , as well as in the

inner-voice E-E

, as well as in the

inner-voice E-E![]() -E in m. 9 at the close

of this piece).

-E in m. 9 at the close

of this piece).

The final movement also affirms the

quartal process and connects it with the opening of the work. The second half

of the tolling figure - F G C - is transposed to B![]() F C

in measure 6, and shares two pitches with the F C G cell. In fact, the same

quartal hexachords can be found in both movements:

F C

in measure 6, and shares two pitches with the F C G cell. In fact, the same

quartal hexachords can be found in both movements:

VI 6 m. 6

D

G C F B![]() (D# in

previous measure)

(D# in

previous measure)

I,

m. 2

D

G C F B![]() (rh) (D#

in previous measure)

(rh) (D#

in previous measure)

Figure 7:

Schoenberg, Comparison of ic5

Collections in Op. 19, I and VI

This

emergence is based on the accumulation of a number of details throughout the

work (excepting the third-obsessed piece II).

-

The left hand pitches in III, mm. 1-2 can be expressed

as a fourth cycle (A![]() E

E![]() B

B![]() F C),

which shares three pitches with the quartal material in VI, (B

F C),

which shares three pitches with the quartal material in VI, (B![]() F C);

another quartal figure follows in measure 3 (A D G A C).

F C);

another quartal figure follows in measure 3 (A D G A C).

-

The F C G D subset appears in IV, m. 4 in the

left hand, and also in mm. 11-12.

-

A nearly complete quartal hexachord con be

found in V, m. 8: A# C/G F/D, where the G C and F are in their original

register in I.

The chart in Figure 8 traces the

emergence of perfect-fourth intervals with triangular note heads indicating

those in their original registral positions in. I.

Measure 9 contains the pitches C F#

G G# E![]() E, all of

which (except for C# and D) appear in I, measure 1. Note that the measure 9

pairing of AUG0 and AUG1 also references I, m. 1. The pair

of symmetries 5/5 and 10/10 at measures 6-7 point toward the final measure -

and the end of the work - which closes with a symmetrical 14/14 (B-A / B

E, all of

which (except for C# and D) appear in I, measure 1. Note that the measure 9

pairing of AUG0 and AUG1 also references I, m. 1. The pair

of symmetries 5/5 and 10/10 at measures 6-7 point toward the final measure -

and the end of the work - which closes with a symmetrical 14/14 (B-A / B![]() A

A![]() ) echo wie ein Hauch: “like a breath.”

) echo wie ein Hauch: “like a breath.”

Figure 8: IC5

Collections in Op. 19

Example 6: Schoenberg, Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke, VI