Compositional Uses

of The Crossing Phenomenon In Recent Music

Gerald

Ruffertshoefer Gabel

The

evolution of musical stylistic traits from one era to another has, in part, been

achieved gradually through a particular treatment of musical elements or phenomena

which had been either avoided or unrecognized in previous epochs. For instance,

dynamics were not indicated in music until the early Baroque. Once it was

recognized that composers could more accurately depict a musical idea through

their use, dynamics became an integral force in the shaping of

musical materials. The manner of their implementation contributed to the

characterization of musical style in succeeding centuries.1 Similar evolutionary tendencies

have occurred in relation to other musical elements.

While

engaged in a study of musical texture, it was found that the phenomenon

of "crossing" was being utilized to a greater extent in this century

than in times past. While it is difficult to say that crossing is

characteristic of 20th century musical style, one can argue that its use is important in

the music of composers such as Webern, Xenakis,

Ligeti, Lutoslawski, Nancarrow, Debussy and others. For instance, part crossing occurs

with such regularity in the rhythmically free sections of Lutoslawski's orchestral works that it may be considered a feature of his compositional language. Crossing implies the intersection

of musical phenomena to such a degree

that their relative placement is reversed. Perhaps the most common form is part crossing.2 In this case, the

relative pitch ranges of two or more parts are reversed; the lower part becomes the higher part and the

higher becomes the lower. While it is true

that the crossing phenomenon is seldom employed as a focal structural .element

in the compositional process, the

numerous examples of its use in this century suggest that it is an

exploitable phenomenon which is worthy of observation and discussion.

Since the

crossing of two melodic lines is somewhat common in music from previous

centuries and since the aforementioned article addresses common practice usage;

this paper will focus upon examples from the present century which provide new

insights into the use of the crossing phenomenon. Specifically, part crossing

will be discussed in the context of unorthodox contrapuntal

settings. This will include examples which exhibit atypical melodic construction,

unusual contrapuntal interaction between component lines in a texture, and the

production of part crossing in textures

which feature the accumulation of many component lines (mass-like textures).

There are

also several musical phenomena besides pitch which have been subjected to

treatment, similar to part crossing. One is a technical device utilized in

piano literature

in which the hands physically cross one another. A second technique is the use of different

tempos in concurrent lines. At a designated point in the unfolding of the

composition, each tempo may articulate beat 1 of

a measure simultaneously. Then, due to the

differing temporal rates, they will digress from one another again. One may think of this as a temporal crossing in the formal

sense. There is another crossing

phenomenon that is closely related to temporal crossing. One may create the

illusion of increasing tempo without a tempo change. This is achieved by

decreasing the duration of notes within a line. The pulse remains constant, yet

the increasing linear density of articulations, for example, causes the

sequence to accelerate. A third technique, which

is found only in twelve-tone and serial musics,

features the crossing of various farms

of a row. Finally, the phenomenon of crossing has been extensively applied to the

movement of sound in

musical and physical space.

Part Crossing as a Product

of Unconventional Contrapuntal Procedures.

After the

Baroque era, counterpoint became of secondary importance to harmony as the

focal point of structural organization in music. By the turn of the twentieth

century, tonal practice had been stretched to the point that composers had

begun to search for alternative modes of construction which

would instill their creative endeavors with new vitality. One of the primary

developments was the gradual re-implementation of contrapuntal devices. As the harmonic

vocabulary became more inflected and the limits of tonality tested to the

extreme, greater emphasis was placed on linear relationships in order that composers might

maintain adequate control over compositional materials. This "reactivation of the

polyphonic evolution" took place primarily

in the music of Arnold Schoenberg and his disciples Anton Webern

and Alban

Berg.

Anton Webern's music portrayed an extended view of the traditional

contrapuntal implications found in Schoenberg's music. The lines

that make up Schoenberg's textures were constructed according to traditional

rhythmic percepts, were distinguishable as independent lines, and were combined

according to traditional considerations of complementary rhythm. Schoenberg's treatment of

the row was thematically oriented. On the other hand, Webern

utilized it as a more abstract phenomenon and did not view it as a source for

melodic construction. In fact, he tended more towards condensation and

fragmentation (or athematic construction)

particularly in terms of rhythm.

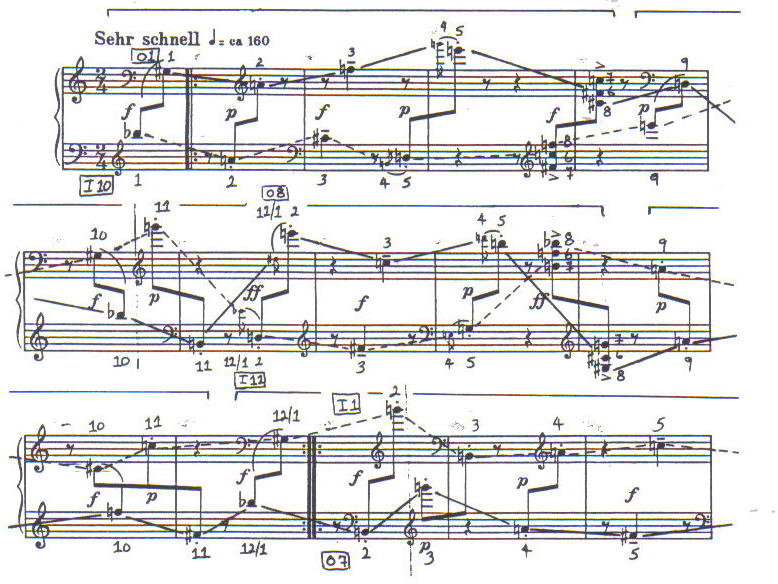

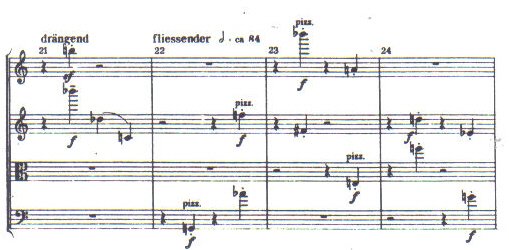

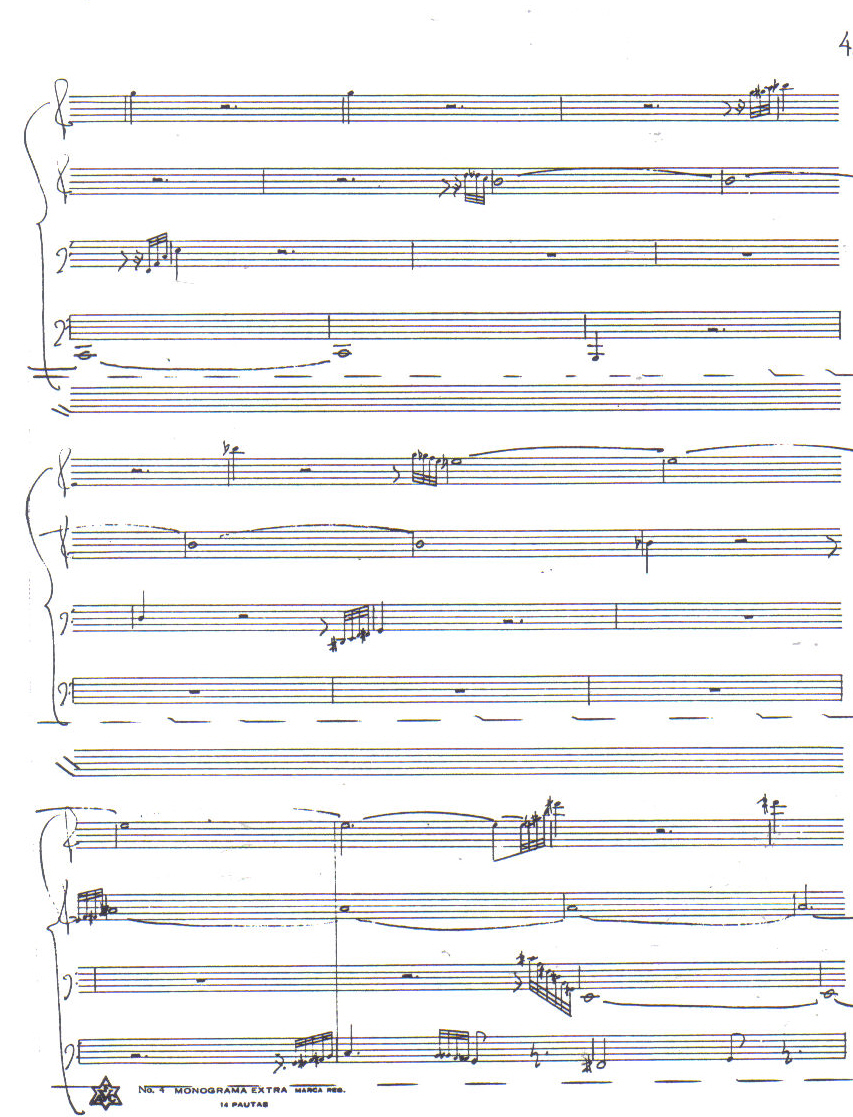

It is

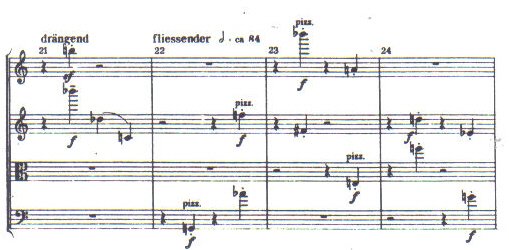

important to consider the extent to which linear elements can be called lines in Webern's music. Example 1, extracted from the first

movement of the String Quartet, Op. 28, illustrates

the angular and fragmented nature of his "melodic" construction.

Not only are the two note groupings indistinguishable as lines, but they are separated

by internal silences of equivalent duration, further inhibiting their perception as lines.

Instead of a texture of lines, one finds a texture which is frequently called " pointillistic." The

paradox is that even though we are dealing with music that is strictly

canonic, it cannot be called contrapuntal in the traditional sense. Although

Example 1 is set in canon, one hears only a series of independent two note

groupings. Having been integrated as an important structural element,

the silences disrupt not only

the sense of linearity but also the sense of contrapuntal flow.

There was

also a marked tendency towards angularity (disjunctness)

in Webern's use of intervals linearly. This resulted in part

crossing. Webern's use of angularity

contributed to a lack of separateness and, thus, to the equivalence of parts. Through the

initial viola entrance in Example 1, the domains of the parts remain relatively distinct with minimal

incursion from each other and no instances of crossing.

Example 1: Webern's String

Quartet, Op.. 28

First

Movement, mm. 22-24

Copyright 1939 by Hawkes

& Son (London) Ltd., Copyright assigned 1955 toUniversal

Edition A.G., Wien. Copyright renewed. All rights

reserved.Used by permission of European

American Music Distributors Corporation, sole U.S. agent for Universal Edition.

In the third measure, the situation

alters noticeably. On the second beat, the viola (F5)4 crosses the second violin part (D5).

This is immediately followed by the violoncello (G4) crossing with the second

violin (E flat 4), significantly affecting their relative placement. The combination of angular intervallic

successions and pointillistic texture creates a considerable number of crossings. Without a

doubt, Webern utilizes the technique

to such an extent that crossing may be considered characteristic of his style.

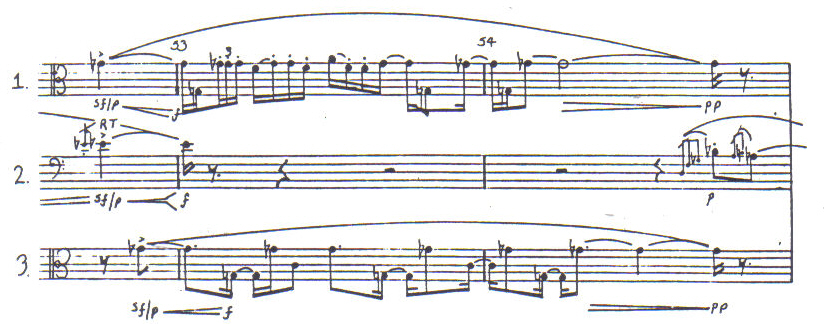

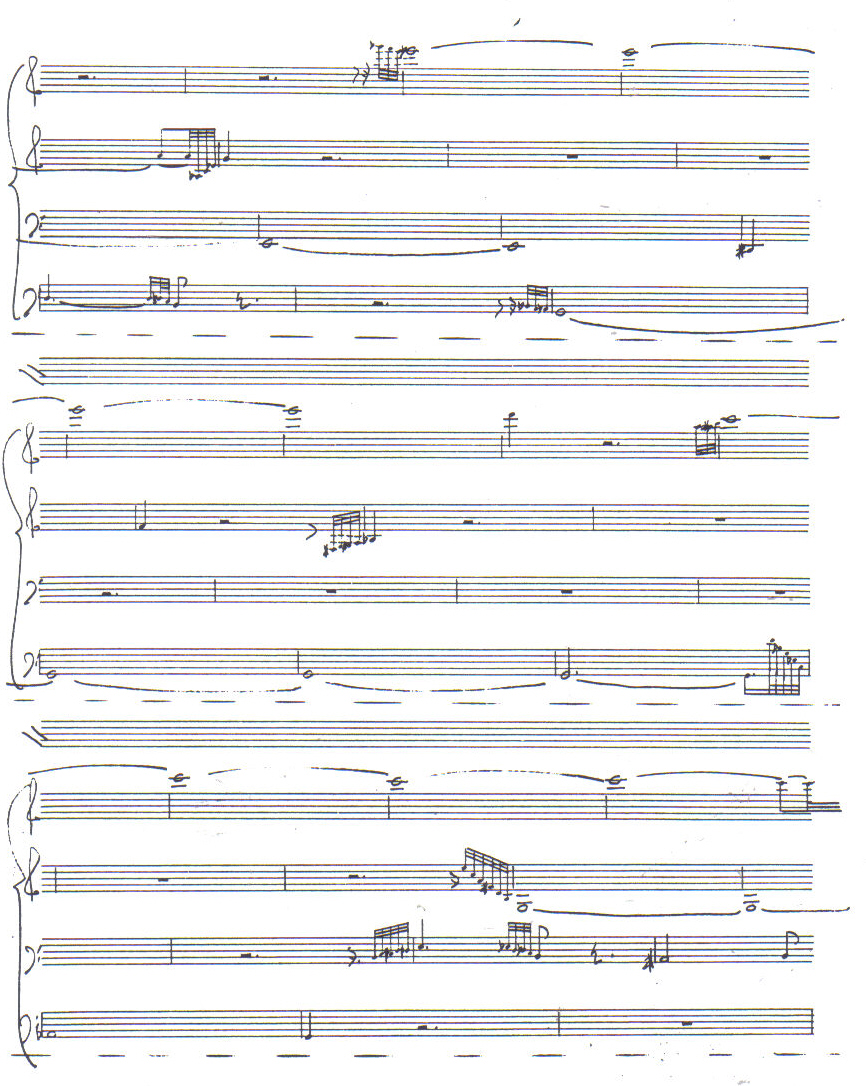

Part

crossing may also create a lack of separateness even in textures which feature a more traditional melodic design. Beginning in

m. 52 of my Saraph for Three Bassoons (Example 2), lines one and three engage in a two measure passage which features a predominance of wide skips. Unlike Webern, this example does not feature skips beyond the octave, nor are rests functional in the

melodic construction. Nevertheless,

one confronts a similar unrelenting invasion of the parts into one another's pitch domains. In fact, the domains of the two

parts are virtually the same. Until

the third beat of m. 53, they do not engage in crossing to any appreciable

degree. On the first beat

of m. 53 the first part does supersede the third. Since they had only engaged in a unison up to this

point in the example, it is premature to call this a crossing since the first line returns to the unison before any

pitch change in the other one. Beginning

with the fourth beat of m. 53, they begin a series of crossings which culminate

with the return of the original Unison. Due primarily to the number of unisons on the pitch E flat 4, they never achieve melodic

independence. This is evident even prior to the point at which they engage in crossing. The singular nature

of the shared domain coupled

with the persistent articulation of a unison and subsequent crossing, lock them

into a singular identity; a complex, angular texture with Eb4 as the focus of pitch

activity.

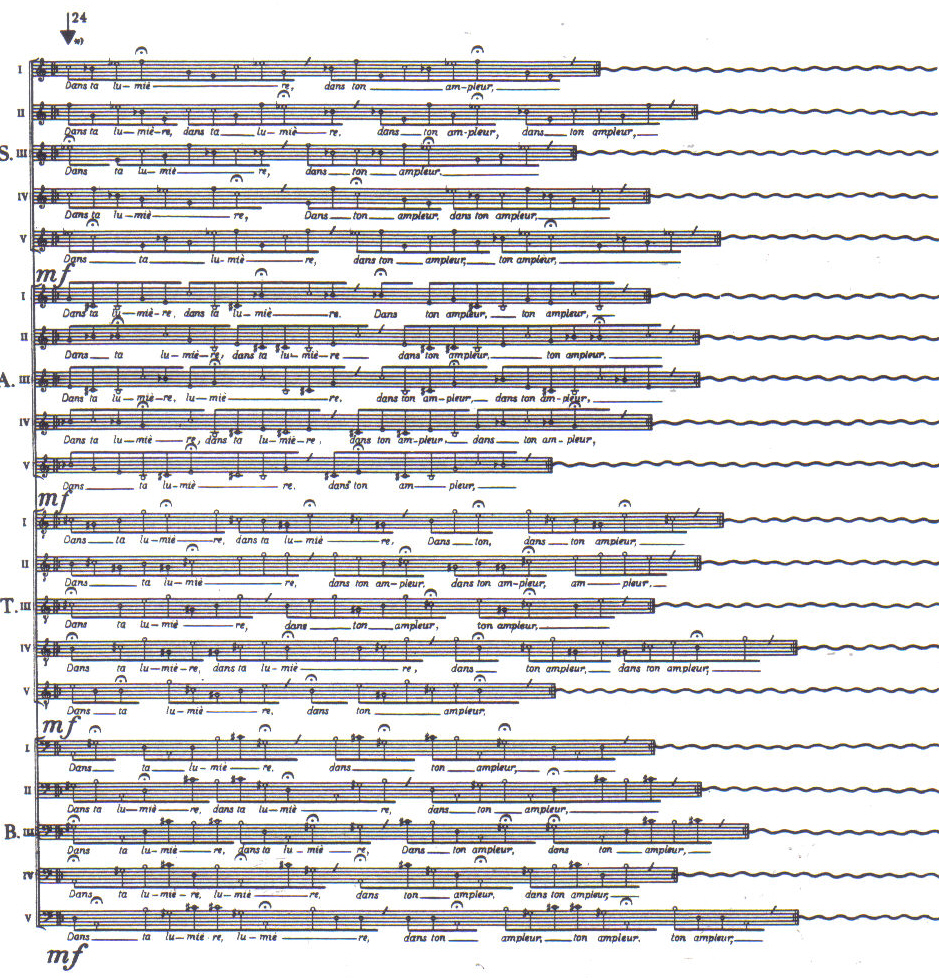

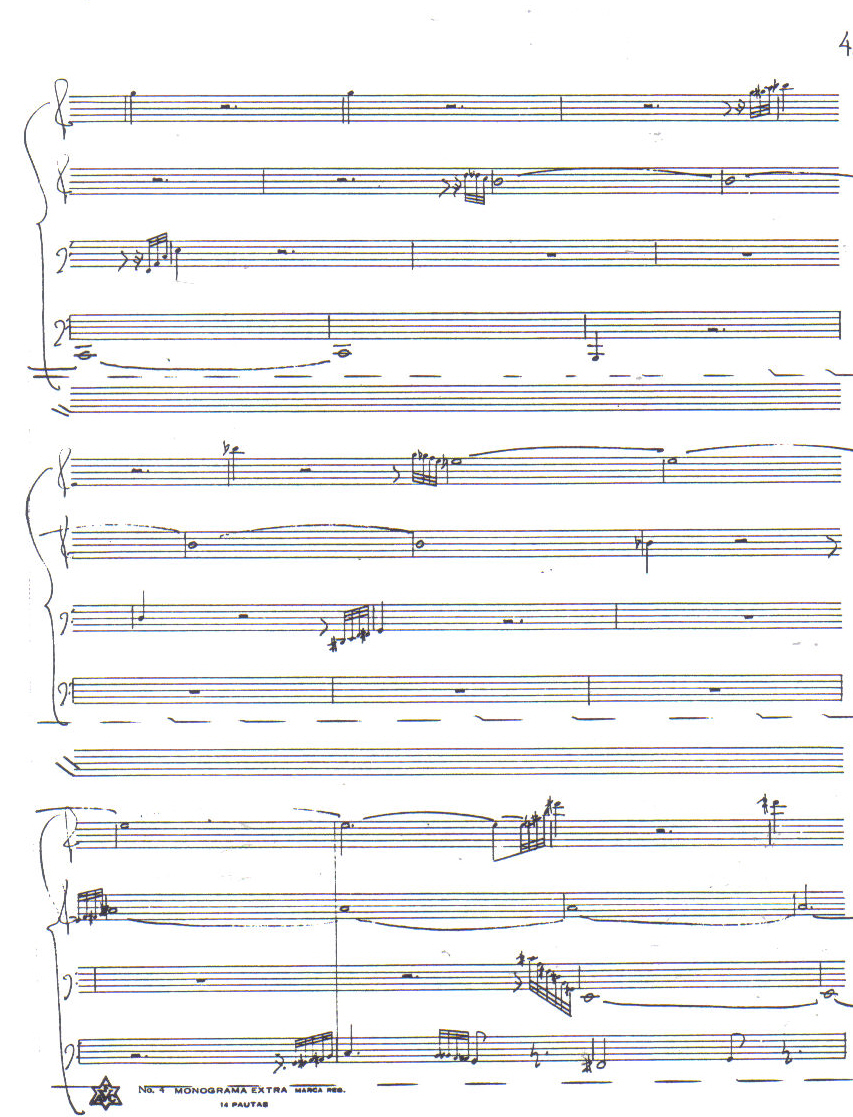

Another

example of crossing in an extended contrapuntal setting is found at rehearsal 24 of "Repos dans le Malheur" from Trois

Poernes d'Henri Michaux by Witold Lutoslawski (Example 3). The texture is

characterized by a plethora of crossings which are achieved through the massing technique. It involves the

accumulation of, at times, an

extreme number of independent, imitatively conceived parts (in this case 20).

In effect, the individual attributes of each line are subsumed into a global identity: the texture of the passage. The domains of the

vocal sections within the choir overlap

considerably. However, each choral section contains five lines which evolve independently of each other. Lutoslawski called this "collective ad libitum." By

this process, each performer proceeds at his own pace.

In the performance instructions Lutoslawki

writes:

The duration of the notes is in general free, except for

those having pauses, which should be longer

than the others. The greatest naturalness in sound-production and interpretation is recommended. Thus, the more difficult

intervals may be attacked slowly and the

easier ones more quickly. The performance of the whole section, however, should be free of haste, for which reason the

duration of the individual notes should not be less than 0.5

seconds.5

One can expect significant part

crossing within each choral section as well as between them. Following individual lines is impossible under such

circumstances, which, in this instance, is

the desired result.

Example 2: Gabel's Saraph for Three Bassoons, mm. 52-54

The Application of the Crossing Phenomenon to Elements

Other than Pitch

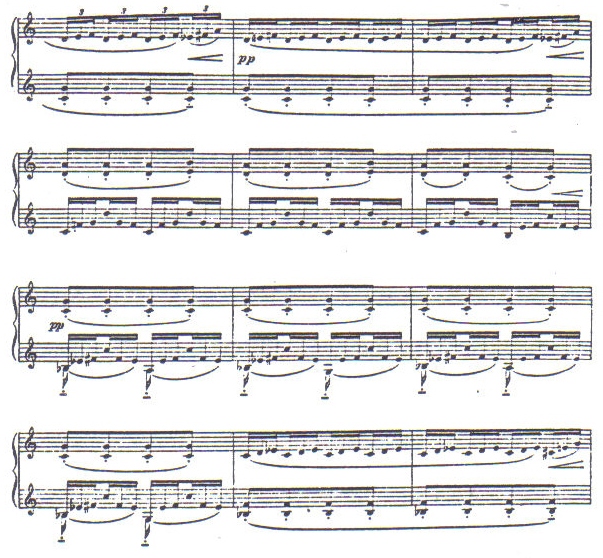

Claude Debussy

utilized the technique of hand crossing in his keyboard music. However, he did not always maintain distinct

placement of the domains in which the hands'

parts were played. As a result, they often overlapped or shared similar (at times

even the same) domains.

In

the third movement of Images

I for piano

(Example 4), the left hand harmonic

support encompasses the domain of the right one. In measure six (on the fourth beat), the domain of the

right hand part extends a whole step beyond that of the left. In m. 9, the harmonic material shifts to the

right with the melodic line belonging

to the left hand. In this instance, the melodic line maintains the low and high portions of the passage's pitch range while at the

same time passing through the interval

of a perfect fifth outlined in the right. In m. 16, the functional role of each

hand again reverses with the right assuming the melody and

the left the harmony. Debussy

has thus not only allowed the hands but also the harmonic and melodic functions

to "cross."

Example 3:

Lutoslawski's

"Repos dans le Malheur"

from Example 3 of Lutoslawski's "Repos dans le Malheur" from Trois Poemes d'Henri Michaux, Rehearsal

numbers 24-25

Reproduced by kind

permission

of the copyright owner, & W Chester/Edition Wilhelm Hansen

London Ltd.

Webern's

Piano

Variations, Op. 27 is an excellent example of the

extended use of crossing. Two types are found in the work: row and hand

crossing. The second movement (Example 5a)

is a strict canon in contrary motion. The subject begins in the left hand and

is imitated at the temporal interval of an eighth note in the right. The original form of the row is found in the

right hand (01) at the beginning of the movement. A cursory look through the example reveals that the last note

of the realization of one row is

simultaneously the first note of the realization of the next row form in the same hand. The hand in which a particular sequence

of row realizations appears

changes in five places: measures 5, 6, 8, 17 and 18. Each of these crossings produces

a change of function for the rows. In each case, the subject row becomes the countersubject row and vice versa. Additionally,

as the first main section is repeated there is a crossing of the function of

the entire sequence of rows found in each hand. In the initial pass, the sequence of rows indicated by

a solid line begin in the right while

those indicated by a dotted line are found in the left. At the end of this

section this arrangement has been registrally

reordered. Therefore, the repeat will begin with the "dotted line" in

the right hand and the "solid line" in the left and end as the piece began. Ideally, the second main section should

begin with the "solid line" sequence of rows in the right and "dotted line" in

the left. However, for clarity in viewing the unfolding of the rows, it was decided to overlook the repeat at the end

of the first main section. Therefore, the actual row sequences for the

hands are reversed. It is possible that,

since he was not prone to repeating entire sections of a composition, Webern purposefully employed the technique of crossing the row

sequence in order to provide

a structural distinction between the original statement and repetition of both sections

of the movement.

Example

4: Debussy's Images I,

Third Movement, mm. 1-17

Example

5a: Webern's Piano Variations, Op. 27

Second Movement mm. 1 - 14

Copyright

1937 by Universal Edition. Copyright renewed 1965. All rights

reserved. Used by permission of European

American Music Distributors

Corporation, sole U.S. agent for Universal Edltion,

It is a curious trait of Webern's choice of row forms that specific pitch classes in one row always appear in conjunction with specific pitch classes in another row form. As a result, only seven

pitch class diads are formed. They are B flat-G#, B-G, AA,

F#-C#. E flat-D#,

E-D, and C#-17. However, the

succession of these diads changes with each

combination of row forms. Therefore, symmetrical palindromes made up of

these diads do not occur in the movement.

Another focal point in this work lies

in the extension of piano technique through hand crossing and the alternation of the order in which hands

articulate events. In

Example 5b, both of these relationships are shown. Solid vertical lines indicate changes in the order in which the hands

articulate events (i. e., from left-right to right-left or vice versa). The full implications

of this phenomenon are not shown

in the example as only relative pitch ranges are included. There are, points

(for instance, measures 12 and 13) at

which hands must cross to opposite ends of the piano.

Example 5b: Webern's Piano Variations, Op. 27

Hand

Crossing in the Second Movement

In

Anton Von

Webern:

A Chronicle of His Life and Work, Hans

and Rosaleen Moldenhauer

clarify Webern's reason for including hand crossing

in the Variations:

Dwelling on some of the pianistic

details of the work, Stadlen6 referred to the awkward

crossing of hands demanded for the proper execution of of the Scherzo movement movement:

'Webern said that the inevitable difficulty in bringing it

off would invest it with just

the

right kind of phrasing.7

In Example 5a, brackets indicate phrasing based upon Weliern s implementation of hand crossing. Each phrase includes a hand crossing

followed b a reversal of direction to

another crossing thereby re-establishing the placement of the hands encountered at the beginning of the phrase. Therefore, phrase

#1 is wade up of five successive diads, the next phrase by the next seven diads, and the final phrase of the first half of the work

by three dials. The 5 + 7 + 3 construction

is reflected in the second half

although with 'a subtle change. The final diad before

the repeat in m. 11

serves simultaneously as the beginning of the

repeat and as the beginning of the second half of the work. However, the second half, as notated, begin N after the repeat. For phrasing purposes, the fourth phrase begins in m. 11 but the hand

crossing pattern begins at in. 12. With this in mind, the grouping of diads.

into phrases in the second half is 6 + 7 + 3. Webern, then,

had at least two reasons for the sectionalization of this movement. First, the phrase structure (which is conditioned by the ordering of hand crossing) divides it into two groups of three

phrases. The ordering of phrase lengths provides a sense of unity in the first,

half of the movement. Secondly, the row

crossings provide the means by which both halves of the work are repeated. Therefore, crossing principles as related to row

manipulation and phrase structure provide

a tactic for formal sectionalization and unity in

this movement. Unity is also achieved through the

implementation of the limited number of diads.

Unlike Webern's exposure of musical elements to crossing at

various structural levels, Conlon Nancarrow

crosses four tempos in his Canon #36 ( 17 / 18 / 19 20 ) (Example 6a).

Nancarrow's music is important in that not only does

he establish tempo as the primary temporal element but the tempo

relationships themselves are often the modus operandi of his compositional

inspiration. In his article "Inexorable Continuities," Roger

Reynolds wrote:

There is a tendency to think of a musical

element 'rhythm' as though it included

meter

and tempo (in the sense that they are supportive conditions over which rhythmic

invention takes place). Nancarrow, however, seems to identify

tempo as

the prime

temporal consideration and to relegate other time-related elements to lesser

status.8

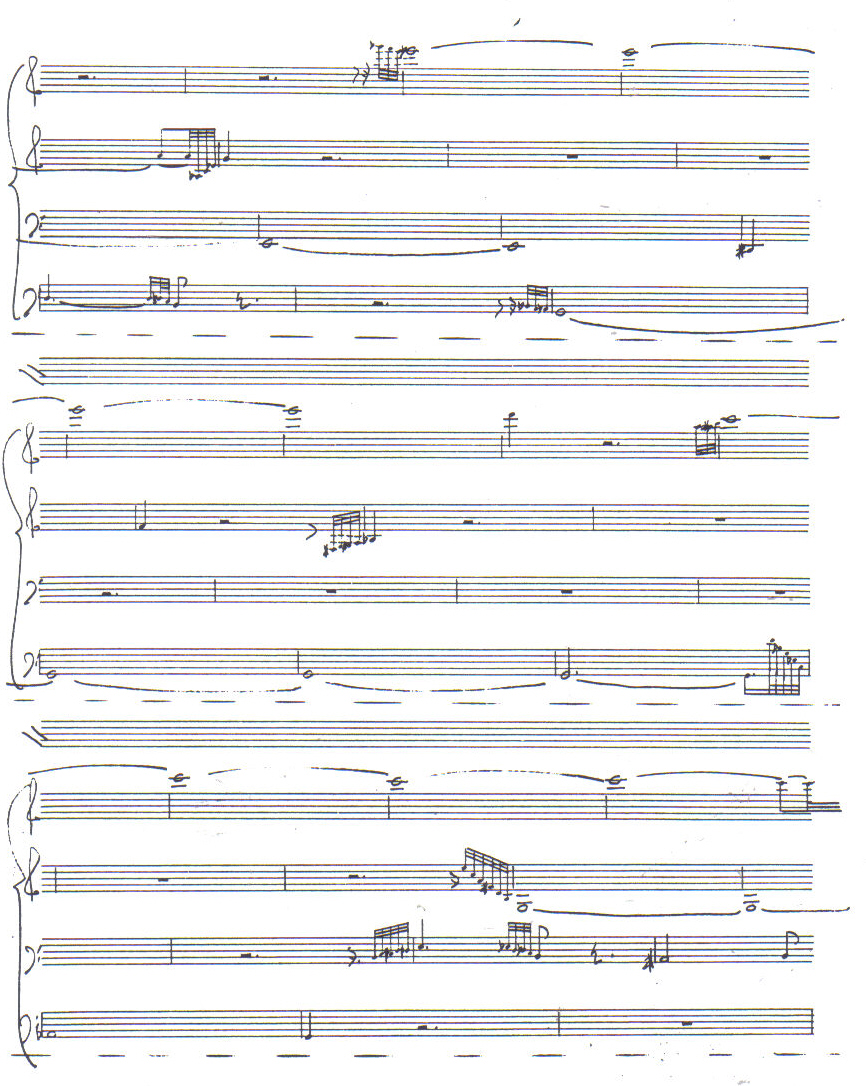

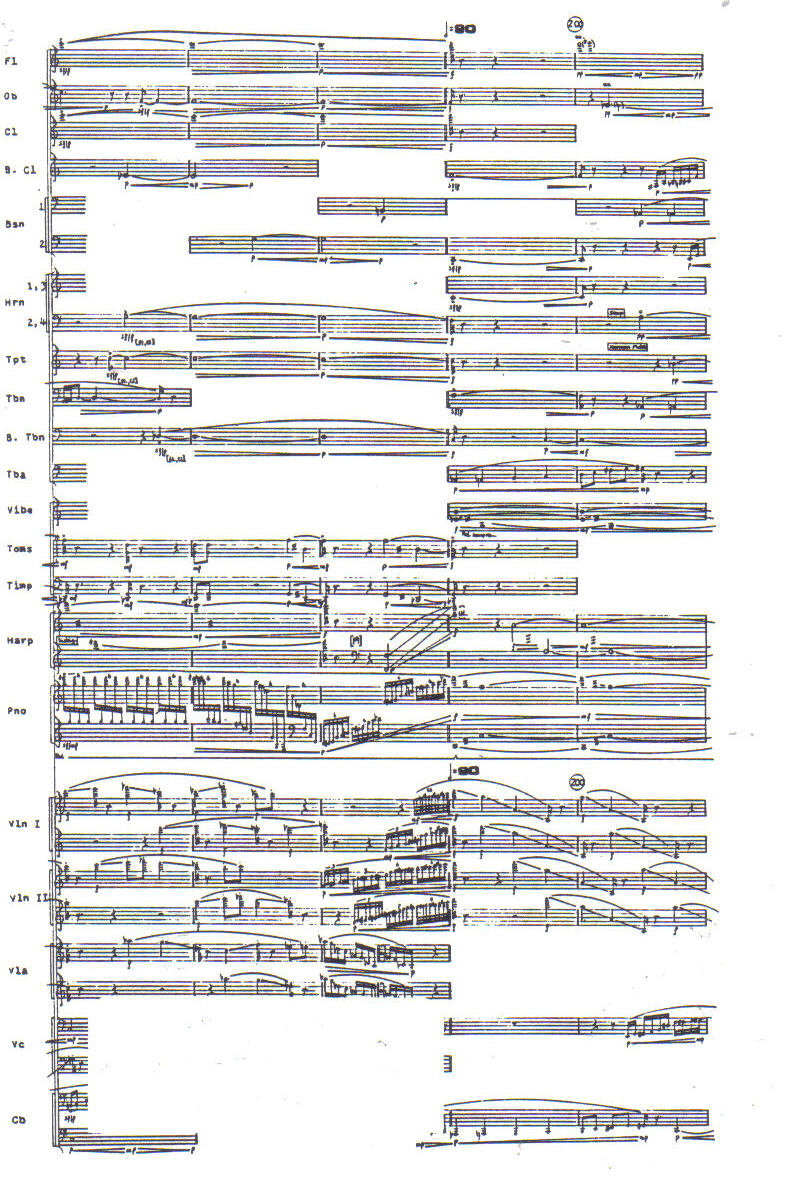

Each of the four lines in Canon #36 possesses a tempo

distinct from that of the other parts.

One line progresses at the rate of a whole note equaling

MM=85, another at MM=90, the

third at MM=95, and the last at MM=100. The ratio of these tempi is the ratio in the title of the work (17/18/19/20). In the

time it takes for the MM=85 line

to progress through 17 measures, the MM=90 line will have stated 18 measures, the MM=95 line 19 measures, and the MM=100 line 20

measures. At this point, all four

parts articulate beat 1 of their next measure simultaneously. There will not be

another simultaneous articulation of

beat 1 in any measure until the cycle has been re-stated. Once all four lines have entered, there are 33

statements of the cycle after which

they one at a time drop out in the reverse order in which they entered. The incessant implementation of the temporal cycle, at times,

acts as a formal delimiter in

the work. In fact, Nancarrow many times effects an

abrupt textural change at points

of temporal simultaneity. As a result, one's sense of expectancy can be, in a sense,

shaped by the anticipated return of temporal simultaneity.

For the

purposes of this discussion, the formal implications are not as critical as the

actual temporal relationships within each cycle. Between any two temporal simultaneities

in the work, the same succession of skewed pulse relationships between

lines exists (Example 6b). As one approaches a point halfway between two simultaneities,

the duration between articulations of the downbeats of measures (in fact of any

beat within any measure) between parts becomes greater. After the half-way point, the duration between

articulations of downbeats gradually decreases (perceptually) resulting in the next temporal simultaneity. This effect

is similar to incursion and excursion

in the crossing of parts (melodic lines). As they incur towards a unison, their

pitch separation decreases. As they, excur from one

another, their separation increases.

It is in this process of incursion and excursion (increase and decrease of distance or duration) that a

similarity exists between the crossing of pitched lines and the crossing of lines with concurrently differing

tempos. However, a difference does

exist between these types of crossing (besides the differences between pitch and time). There is not a real

crossing in the tempo domain per se (at least not in the sense of lines displacing one another as is the case in

the pitch domain). Part crossing is

contingent upon a condition in which the domains of parts have distinction:

they move from separateness to a point of intersection and back to separateness.

However, in Canon

#36 the opposite is the case. The formal inclination of the

tempo cycle establishes an expectancy of intersection. Therefore, the tempo model

moves from intersection to separation and back towards another intersection. Even though the conditions are

very much the same, the results achieved through

pitch and tempo crossing are markedly different.

Example 6a: Nancarrow's Canon #36 (17/18/19/20), pp. 4-6

©1977 by Conlon Nancarrow. Used by permission of the publisher,

Soundings Press

Example 6b: Nancarrow's Canon #36 ( 17/ 18/ 19/ 20) Illustration

of Beat Relationships Within a Temporal Cycle

Another work by Nancarrow,

Study #21, utilizes tempo relationships similar to those found in Canon #36. The manipulation of note duration, from shorter to longer

or vice versa, provides the means by which one may achieve a more localized

and more highly control led rate of change. Furthermore, the

temporal changes themselves tend to fluctuate gradually whereas those in Canon #36 were

stable within

each part. The work is subtitled "Canon X." The

designation "X" is a graphic

suggestion

of the temporal crossing by the two lines in the work. In his article

"Conlon Nancarrow's

Studies for Player Piano," James Tenney described

the temporal effect achieved in Canon

X:

The first part (in the bass) begins at a relatively slow

tempo (3.5 notes/second- the numerical values

here and following are my [Tenney's] own estimates).

The second (treble) voice begins, in the next

system, at a very fast tempo (37 notes/second). From

the beginning to the end of the piece the tempo of the first voice gradually increases, while that of the second voice decreases. A little before the half-way point in the

piece the tempos of the two voices "cross", reversing the fast/slow

relationship between them. By the end of the

piece, the originally fast voice has slowed down from its initial 37 notes/second to a tempo of 2.33 notes/second, while

the other voice has accelerated to an incredible

111 notes per second! The tempo\-changes in the course of the piece are linear functions of elapsed time only when

plotted with respect to note-duration (not tempo

as such), which means- among other things that the rate of change of tempo is itself a function of tempo.

That is, the faster the tempo, the faster the rate of

change of tempo.9

The entirety of this work is an ingeniously conceived

illustration of the process of incursion

and excursion in the crossing of parts. Unlike Canon #36, the temporal crossing in this example is very similar to the model for

crossing in the pitch domain.

There is no consistently repeating cycle of temporal relationships between

parts. Therefore, one's sense of expectation is shaped differently. In Canon,

X, the temporal

relationship begins with a relatively high degree of separateness, proceeds towards a point of intersection, and then excurs to an even greater degree of separateness. The effect is made even more pronounced by

the fact that the pitch relationships between the two parts coincide,

precisely with the temporal relationships. The bass part moves from low to high while the treble moves from

high to low. The pitch

crossing occurs at the same time as the tempo crossing. Therefore, Canon X is a rare example of a "double cross" in which two primary

musical elements are structured such that their

deployment produces a synchronized crossing.

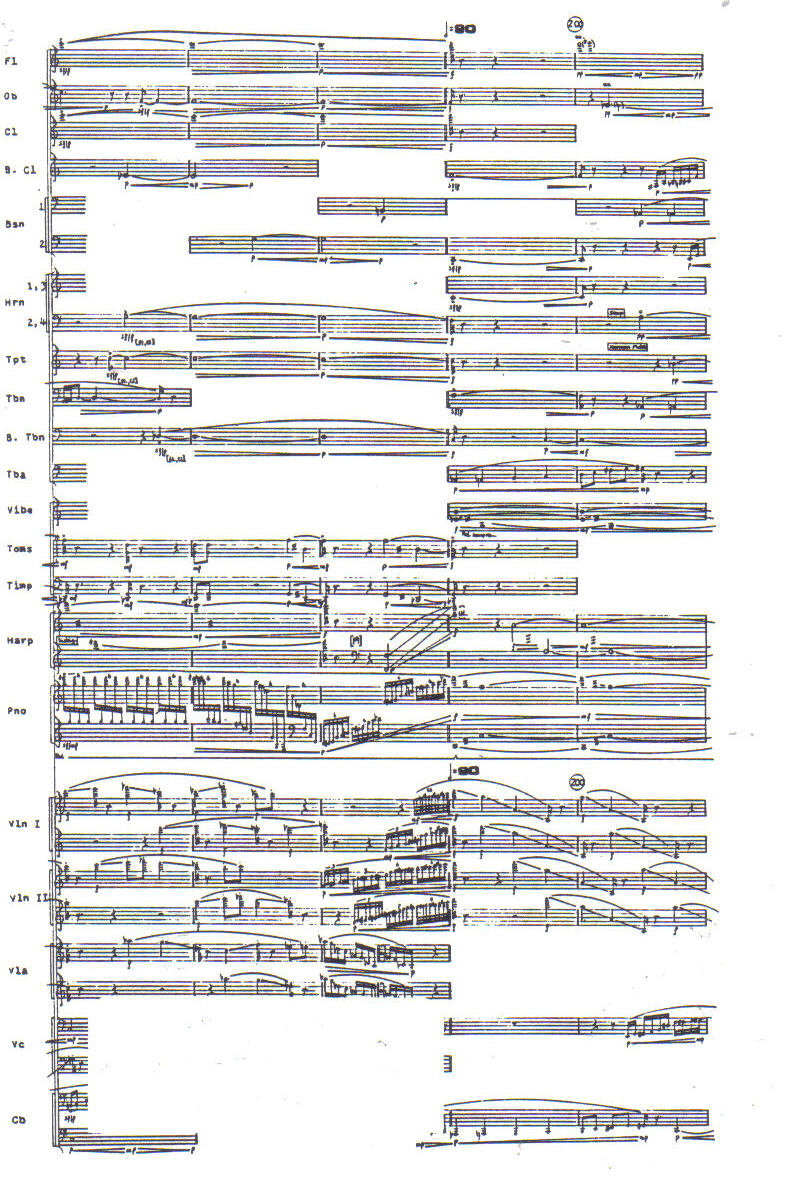

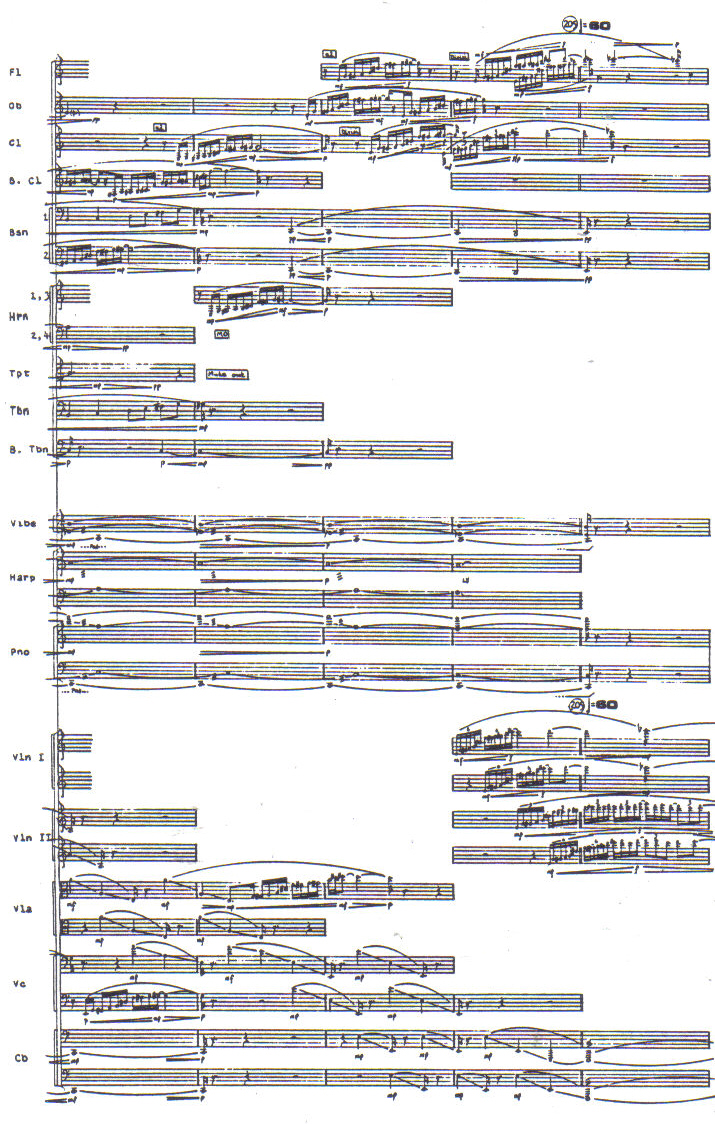

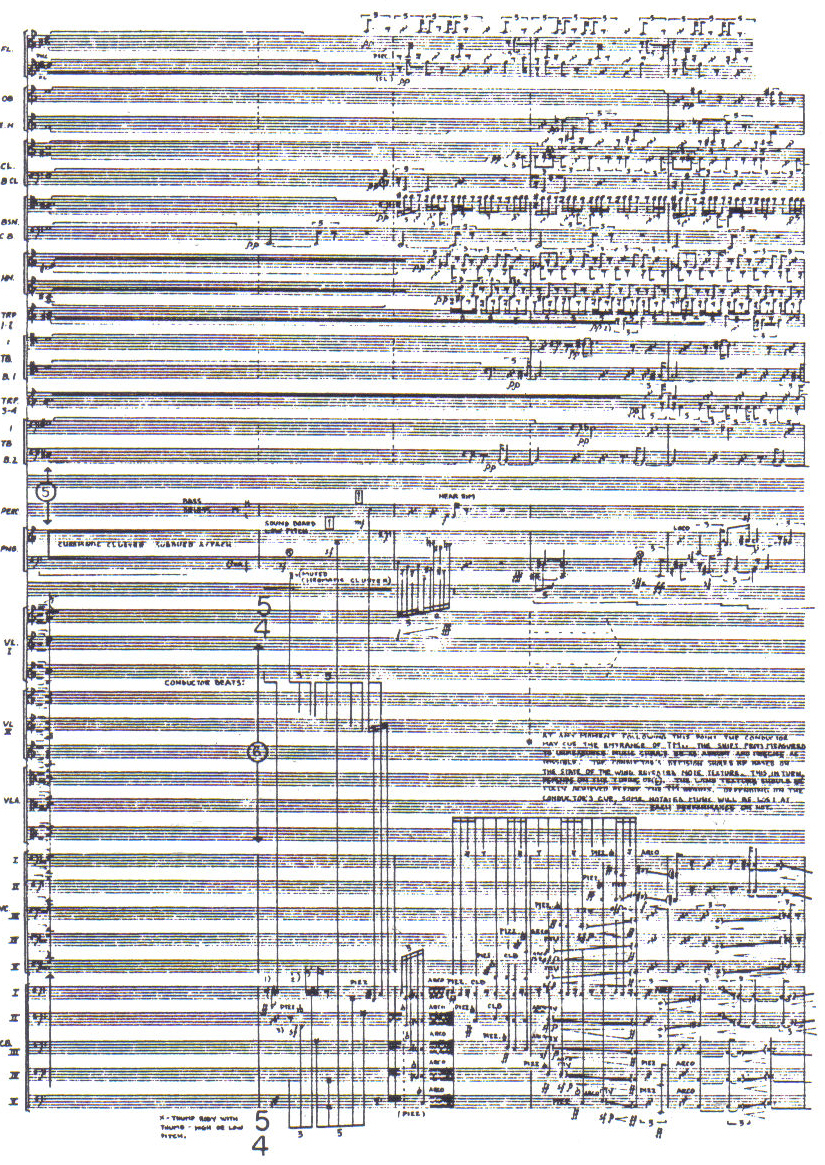

In my work Dragon for Orchestra (Example

7a), the effect found in Nancarrow's Canon X is augmented by increasing the number of

musical phenomena affected by

crossing. One part begins very low in the contrabasses and tuba and gradually increases in both the rate of articulation and

upward ascent. The other, glissandi

in the upper strings, begins very high and gradually descends to the contrabasses (at a lower pitch level than that found at the

beginning of the ascending lines). However,

there is not a decrease in the rate of articulation or, in this case, the distance covered as was found in Nancarrow's example. The glissando maintains a strict one

octave per beat rate. Additionally there is a rather consistent one octave cut-off of the high pitch range every measure (this changes to a perfect fourth in measure 200 in order to end the passage on E1 rather than on A). Even though the crossings occur at the half-way point in the passage (between mm. 199 and

200), they are not structured as

precisely as Nancarrow's. This is partially due to

the rather short length of the excerpt

(approximately 16 seconds as opposed to several minutes for Canon X). Under such compressed conditions it was not

considered necessary to achieve a near

exponential increase or decrease in note duration (or tempo). Instead, primary

consideration was placed upon the effect of a rather sudden and quickly achieved pitch and tempo crossing

as well as a crossing of the paths the

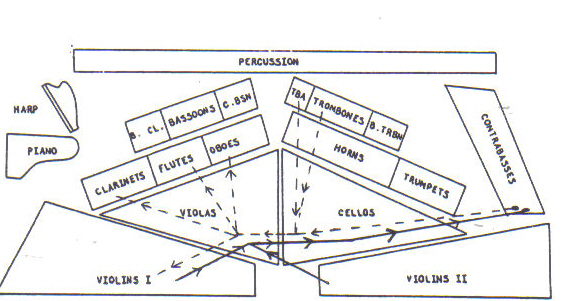

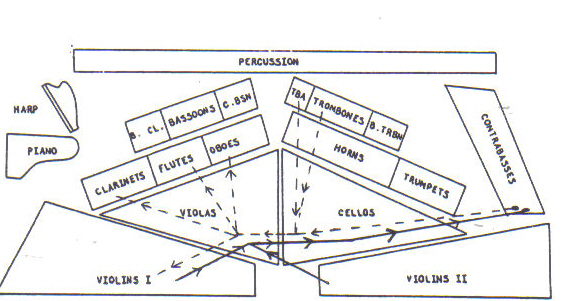

sonic materials would traverse through the physical arrangement of the orchestra on stage. Example 7b shows the intended

arrangement of the orchestra. The broken

lines plot the path of the ascending line as it travels from instrument to instrument in the orchestra while the solid line

plots the path of the descending glissandi.

The basic idea is that the descending line moves from the left side of the

orchestra to the right side while the ascending one moves from right to left.

Not only does crossing occur in the

frequency and tempo domains but also in the spatial and the dynamic domains (the ascending line changes

from "p" to "f" and the

descending line from "f" to " p"

). Altogether, this excerpt from Dragon for Orchestra features four concurrently synchronized crossings

of diverse musical elements and/or phenomena.

Example 7a:

Gabel: Dragon for Orchestra, mm.

197-206

Example 7b:

Orchestral Seating Plan in Dragon for Orchestra

Many of the

examples cited in this paper are from works traditionally performed in

a proscenium arrangement, with the performers arranged in close proximity to one

another facing the audience. The listener is faced with the task of attempting

to isolate and "hear out" lines which are engaged in part crossing

and which emanate from a single spatial locale. If, on the

other hand, the instrumental forces are separated in physical space, the listener may

attend to sounds emanating from more than one location which may enable him/her to

avoid confusion of the functions of crossing parts. This makes it possible for

sounds to be separated in space. This manipulation has emerged as an important

phenomenon in recent compositional

practice.

In several

of his works, • Roger Reynolds utilizes the manipulation of physical and

musical space as a primary structural element. His conception of space as an organizational

element involves the physical dispersement of

performers (or groups of performers) within the performance space. Space is

also utilized as an expanse through which sounds can be passed from one performance

group to another (or from one loudspeaker to another). In Quick Are the

Mouths of Earth, he experiments with three types of spatial interplay between three

groups of performers: 1) clusters of marked entrances which emanate from all locations

within the ensemble; 2) the passing of similar materials from group to group; and 3)

the continuous flow of one sound from left to right (or right to left, etc.) across

the ensemble. The results, though sometimes extremely delicate, and

subtle, are very effective if there is sufficient separation between

the groups of performers.

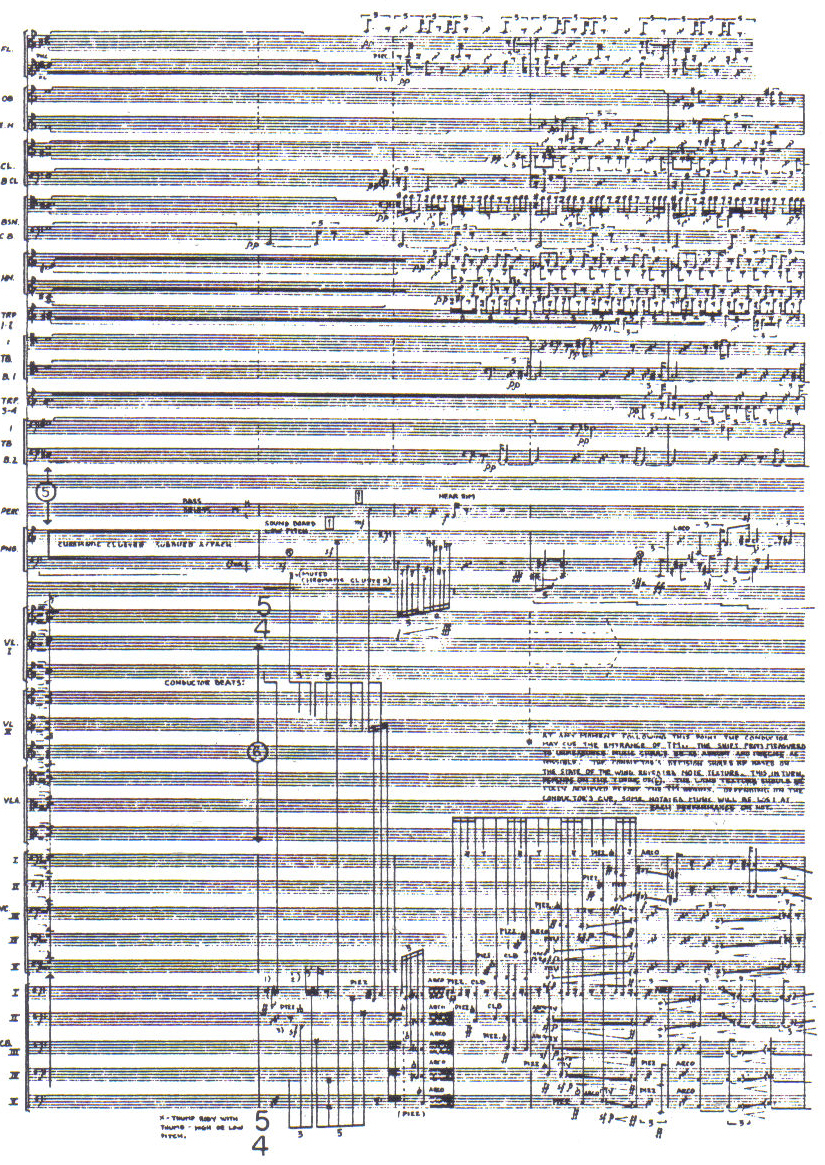

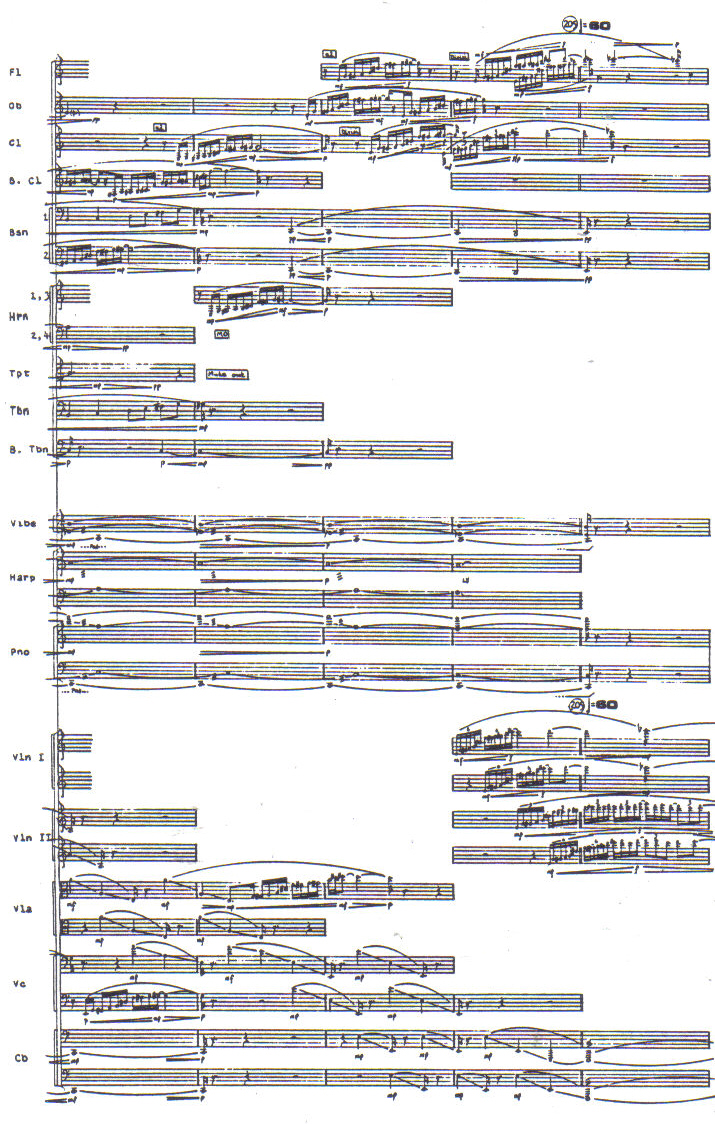

At measure

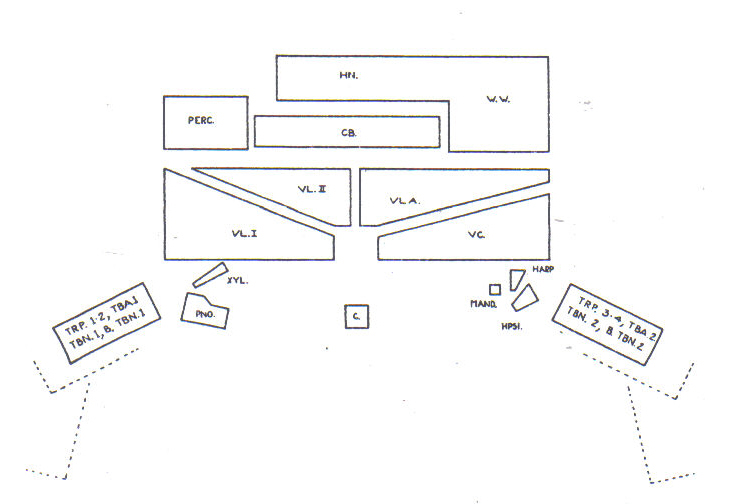

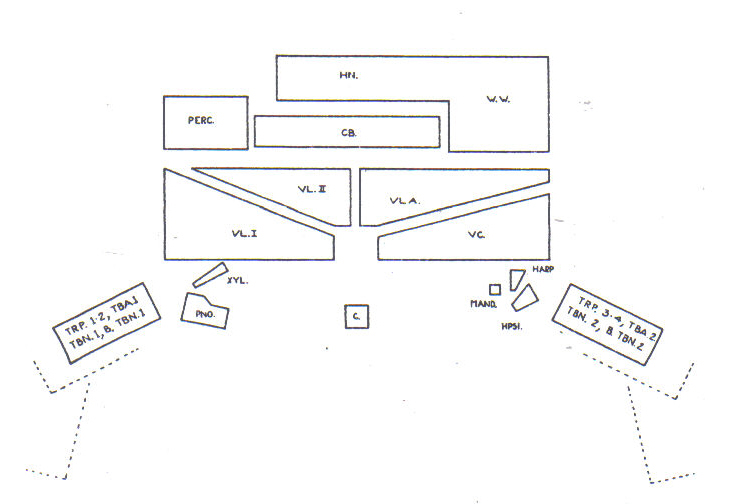

62 of his Threshold for orchestra (Example 8a), Reynolds passes a chordal structure intact from the strings to the winds.

However, the designated seating arrangement of the orchestra (Example 8b) shows

that the chord does not move toward the back of the stage (which would have been

the case with a conventional arrangement) but backwards to the horns, back to

the right to the woodwinds, forward to the right to a brass group, and

forward to the left to another brass group. As a result, the chord radiates in

all directions from the center to

the outer periphery of the orchestra. In the interchange from strings to winds,

pitch components of the

chord can be thought to move and cross in space.

Example 8b:

Reynolds' Threshold pp, 6-7

Copyright ©1969

by C. F. Peters Corporation. Used by

permission.

Example 8b:

Orchestral Seating Plan in Threshold

The spatial deployment of performers

is still undergoing experimentation. The electronic media of synthesized and computed sounds emanating from

loud speakers at

various locations within or surrounding a performing space are providing the composer with greater control in working with musical

and physical space than is

possible by conventional means. The manipulation of space is becoming increasingly integrated into the practice of musical composition.

This is partially true because

more sophisticated instruments (computers, tape, loud

speakers) are available.

Perhaps the most ambitous

experiments with the movement of sound in space were carried out recently by Roger Reynolds. While

not specifically researching

the crossing of sounds in space, his work does provide a basis for realizing

greater control of this

phenomenon. He summarizes his thoughts on the manipulation of sound

in space in the article "Interview: Reynolds/Sollberger:"

"RR: The Poeme Electronique [by Edgard Varèse] and Gesang der Junglinge [by Karlheinz Stockhausen} were done with a concern for the spatial

properties of sound. What seems to me

absent there was an effort to discover what it is that constitutes a memorable, perceivable gesture within the field of

movement. In other words, we know that we can

notice the changing of position and the changing of relative size and speed...of sounds. But whether all these patterns of

movement would be equally memorable or equally

perceptible is not known. Nor do we know anything about the impact of changes in the nature of the illusory "host

space" in which the sounds move.

HS:

You're talking now about developing a language or a vocabulary

RR: Yes. Just quantifying, being able to build structures,

to make the spatial properties of sounds and the change of spatial properties

of sounds in some sense a structural

dimension of music in the way that dynamics became, the way that timbre became, to a degree. I think there's no question that

this is in the offing, and that, of course, computers are the key

to that."

10

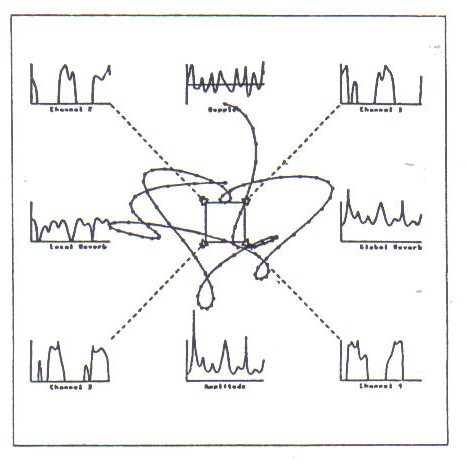

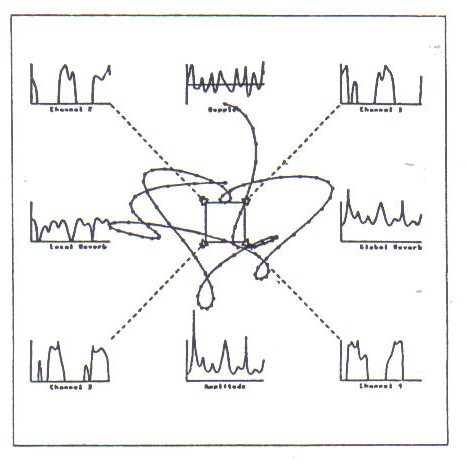

In his recent works, Reynolds very precisely plots,

calculates, and computes the sound

paths and space functions of sonic events in his compositions. The graphic representation of some of these paths and functions

(Example 9) illustrates the highly complex

nature of the sound paths.

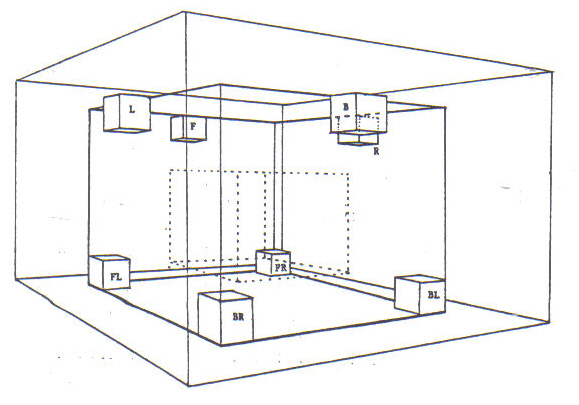

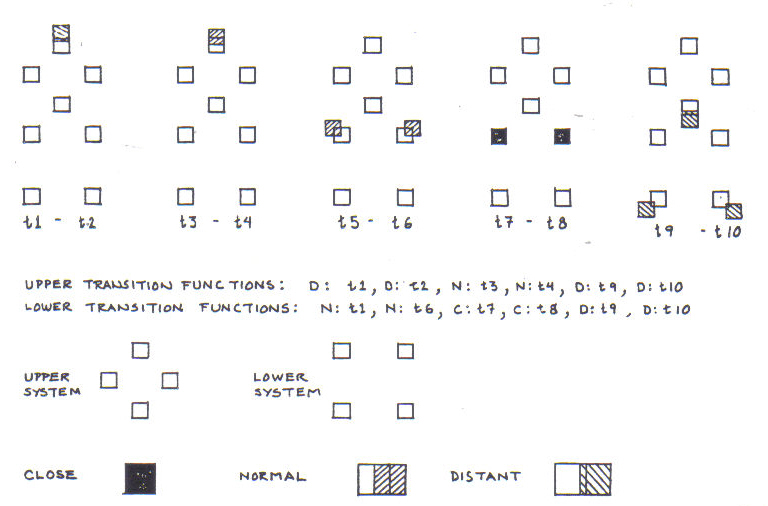

In Archipelago, Reynolds explores a means by which the movement of sound in space can be precisely and effectively simulated. In

discussing the desired effect he writes:

The liquid metaphor I adopted allows one to view sound as

a fluid medium that can emanate from

one point in space, spread out - perhaps surrounding the

listener- and then contract again into a different final position:11

The proposed effect is an illuminating metaphor for sounds

emerging from afar and receding into

the distance. Example 10a illustrates the eight channel speaker configuration which was used for the. premiere of Archipelago at IRCAM in Paris. The use of eight channels, as opposed to the more conventional two or

four channel model, maximizes" the variety of

movement patterns - of paths or shifting

expanses.12

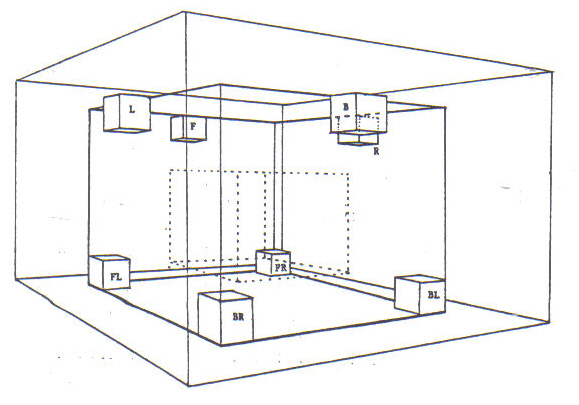

The configuration uses two quadraphonic systems. The upper

system is rotated 90

degrees in relation to the lower system and is located slightly outside the quadrangle formed by the lower system. Reynolds graphs

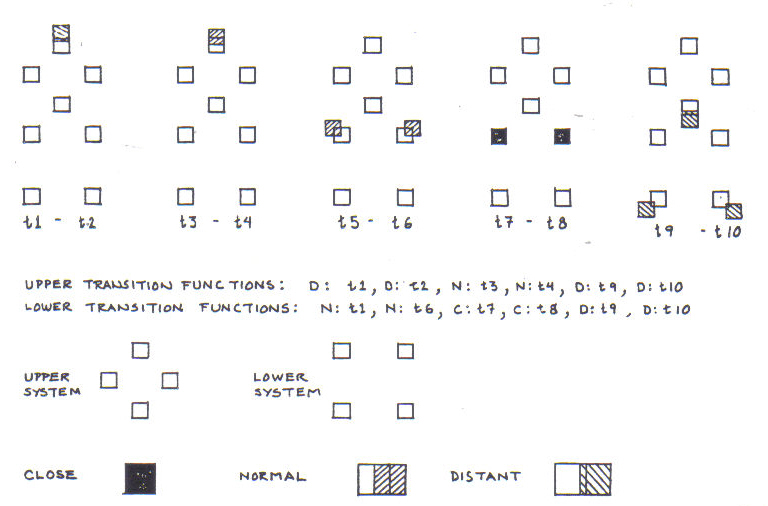

the sound flow paths of each sound event

(Example10b). This graph illustrates that sounds move between close, normal, or distant references. An important

cue for distance is given by the amount

of reverberation present in the signal. The greater the relative amount of reverberation the greater the sense of distance.

At times 1-2, the sound is distant and

located in the front speaker (refer to Example 10a for speaker location). For times 3-4, the sound is located in the same

speaker but has become more present with

a specification of normal. At times 5-6, the sound spreads out to the front left

and front right speakers with a

continued normal distance cue. For times 7-8, the sound becomes very present in the same two

speakers. Finally, at times 9-10, the sound

moves to the back, back left, and back right speakers, ending in the distance. For times 1-8 the sound not only gets louder but

it also seems to become more present

spatially before quickly "passing" to its final destination at the

rear of the hall.

Example 9: Reynolds' Voicespace

IV, The Palace

Location

Sequence Stencil for Pulse Trains

From Roger Reynolds: Profile of a Composer.

©1982 by C. F. Peters

Corporation. Used by permission.

The speaker configuration and its manner of usage in Archipelago

suggests significant potential for the production

of diverse crossing effects. The primary factor is the additional number of speakers from which

sounds may both emanate from and move

toward. Furthermore, the combination of two distinct spatial levels creates a multitude of new possibilities for the

transmission of sound through space. It is possible that Reynolds'

speaker configuration might be a step towards the construction of halls specifically designed for the performance of

electronic and computer generated

music. Such a performance space of the future might have as many as

200-300 speakers13 placed at pre-determined locations in the walls,

ceiling, and floor. Thereby,

the composer would be able to realize a formidable number of spatial

paths. A facility of this type could become a vehicle by which new investigations into

the nature of sounds crossing in space could be realized. Not only would one be able

to conduct extensive research into basic relationships of the spatial crossing

of sounds, but also one might be able to discover those relationships which produce

ultimately effective crossings of sounds in space. These researches could

contribute to the codification of a new musical/theoretical discipline - a

"counterpoint" of sorts based upon the combination of sounds

at various "points" in space. Crossing principles may not prove to be

the only motivating force in the generation of a new

contrapuntal art. However, they will undoubtedly be a topic of importance within the general scope

of "spatial counterpoint."

Example

10a: Loud Speaker Configuration in Archipelago

Example

10b: Graphic Specification of a Sound Flow Path in Archipelago

Bibliography

Gabel,

Gerald R., The Effects of Part Crossing Upon

Musical Texture, University

Microfilms, Ann Arbor, Mich., 1984.

Lutoslawski,

Witold, Performance note from Trois

Poemes d'Henri Michaux, Polskie

Wydawnictwo Muzyczne,

Warsaw, Poland, p. 48.

Lutoslawski, Witold, "About the Element of Chance in Music," Three Aspects of New Music, Nordiska Musik Forlaget,

Stockholm, 1968.

Moldenhauer, Hans, and Moldenhauer, Rosaleen, Anton

Von Webern: A Chronicle of His Life and Work, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1979.

Reynolds, Roger, "Inexorable Continuities," in Conlon Nancarrow: Selected Studies for Player Piano, Garland, Peter, ed., Soundings Press,

Berkeley, 1977, p. 28.

Reynolds, Roger, "Making a Musical Experiment,"

Unpublished, 1982.

Reynolds, Roger, and Sollberger, Harvey, "Interview: Reynolds/Sollberger," in Roger

Reynolds: Profile of a Composer, C. F. Peters,

Corp., New York, 1982, p. 26.

Tenney, James, "Conlon Nancarrow's

STUDIES for Player Piano," in Conlon Nancarrow:

Selected Studies for Player Piano, Garland,

Peter, ed.,

Soundings Press, Berkeley, 1977.

1 For

example, terraced dynamics are very characteristic of Baroque music and sudden

shifts from soft to loud • and vice versa (the

Sturm und Drang principle) are found in the Classical

period. Gradual transitions from one dynamic level

to another as well as their vastly increased implementation are characteristic

of the Romantic era.

2 For

a detailed discussion of part crossing see the author's "The Effects of

Part Crossing Upon Musical Texture" which

is listed in the bibliography.

3 Leibowitz,

Rene, Schoenberg and His School, Da

Capo Press, New York, 1949, p.43.

4 The

nomenclature for pitches is based upon middle C as C4. Therefore, the C an

octave above middle is called C5. The C an octave

below middle C is called C3.

5 Lutoslawski, Witold, performance note from Trois Poetnes d"Henri

Michaux, Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne,

Warsaw, Poland, p. 48.

6 This refers to Peter Stadlen

who premiered the work on October 30, 1937. Weber coached Stadlen in preparation for

the concert.

7 Moldenhauer, Hans, and Moldenhauer,

Rosaleen, Anton Von Webern:

A Chrw, felt- Hi.s.

Life and Work, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1979, p, 484.

8 Reynolds,

Roger, "Inexorable Continuities," in Conlon Nancarrow:

Selected Studies for Player Piano, Garland, Peter,

ed., Soundings Press, Berkeley, Ca., 1977, p. 28.

9

Tenney,. James "Conlon Nancarrow's Studies for Player Piano," in Conlon Nancarrow: Selected

Studies for Player Piano, Garland,

Peter, ed., Soundings Press, Berkeley, Ca., 1977, p.

54.

10 Reynolds, Roger, and Sollberger, Harvey, "Interview: Reynolds/Sollberger," Roger Reynolds: Profile of 4 Composer,

C. F. Peters Corp., New York, 1982,

p. 26. Reynolds, Roger, and Sollberger, Harvey, "Interview: Reynolds/Sollberger," Roger Reynolds: Profile of 4 Composer,

C. F. Peters Corp., New York, 1982,

p. 26.

11

Reynolds,

Roger, "Making a Musical Experiment," Unpublished, 1982, p. 10.

12

Ibid.,

p. 10.

13 There have been installations developed which either

approach or exceed these specifications. In particular, one is reminded of the famous Phillips Pavillion at

the Brussels World's Fair and certain structures developed by lannis Xenakis. However, such

facilities are few in number. It is hoped that, as

the technology is developed, such studios and performance spaces will become

more commonplace.