“Waves” in Debussy's Jeux

Eduardo

Larín

A

notable feature of Debussy’s Jeux

is the cyclic musical process. This process is characterized by motivic

particles recycled within a series of waves, and is part of a duality of continuity

and discontinuity found within the piece. Moreover, although there are

discontinuous elements within Jeux,

there is an underlying continuity, largely due to the wave process. The cyclic

process in Jeux results from

the use of motivic-thematic regeneration,

melodic waves, and statistical waves working together,

at different formal and hierarchic levels, and there is a large-scale structure

and temporality which results from the process.

In

Jeux, arabesques and wave

processes co-exist with fragmentation and mosaic structure. The dialectic of

continuity and discontinuity is also highlighted through change, interruption,

inhibition, and reversal of process. The duality of discontinuity and

continuity parallels other general dualities, some of which are expressed in Jeux, including that of object and

process, particle and wave, nonlinear and linear, heterogenous and homogenous,

and others (Figure 1).

|

Discontinuity

|

Continuity

|

|

particle,

motive, mosaic

|

wave, arabesque

|

|

form,

object, duration

|

process, flow,

change, motion, tension, release

|

|

inorganic,

digital

|

organic, analog

|

|

Matter

|

energy

|

|

Static

|

dynamic

|

|

space,

spatial

|

time, temporal

|

|

Simultaneity

|

succession

|

|

synchronicity,

chance

|

causality, progression

|

|

non-linear,

non-directional

|

linear, directional

|

|

heterogenous,

difference, variety

|

homogenous,

similarity, unity

|

|

Tao

|

yin/yang,

increase/decrease

|

|

heaven,

permanence, eternity

|

earth, change,

temporality, beginnings and endings

|

Figure 1: Dualistic

Elements

In

addition, Jeux expresses other

dualistic elements, including Ruwet’s “play of symmetries and asymmetries,”

“the dialectic of the repeated and the non-repeated,”

a dichotomy of diatonic and chromatic materials, and the synthesis of East-West

ideas.

The

idea of a continuity of waves within a modular structure parallels Asian

concepts of time. Concerning the duality of continuity and discontinuity,

ancient Chinese thought emphasizes continuity, waves, and cyclically recurring

change.

On the side of discontinuity, time was divided into parts or phases. Needham

says, “An important question here is how far the individual cycles, or

particular parts of cycles, were compartmentalized, separated off from one

another into discrete units,” that “time in ancient Chinese conception was

always divided into separate spans,” and that “it was essentially discontinuous

‘packaged’ time,” but that ultimately “Chinese physical thinking was dominated

throughout by the concept of waves rather than of atoms.”

Debussy

said “I would like to make something inorganic in appearance and yet well‑ordered

at its core.”

Boulez notes of Jeux, that “the

general organization of the work is as changeable instant by instant as it is

homogenous in its development.”

Debussy also says of the contrasting sections in Jeux, that “the link

between them may be subtle but it exists”

and Eimert notices the juxtaposition of fragments, similar to that of mosaic

and ‘miniature-art,’ while emphasizing the continuous aspects of the piece, the

arabesque-like melodic and statistical waves, motivic regeneration, and

“timbres and flowing tempi.”

Others have also indicated, on the one hand, the discontinuities and incipient moment-form

qualities of Jeux, and on the other hand, various qualities of

continuity.

Cinematography

also integrates continuity and discontinuity, through frame-to-frame changes,

similar to Langer and Zuckerkandl’s concept of virtual time, wherein a

succession of notes creates the illusion of motion.

Cinematography influenced Debussy to create musical fades, slow motion,

freeze-frame, cuts generating musical blocks, creating “a linked series of

images, musical ideas,”

sometimes approaching moment-form, and cross-cutting stratification.

Debussy’s mosaic technique itself contains many elements of cinematography,

with which it shares a focus on the moment. Pasler relates Bergson’s durée

to the focus on the moment in Jeux, process versus object, the duality

of heterogenous elements within a homogenous flow, and “the dialectic of

continuity and discontinuity,” stating that “Jeux embraces both

continuity and discontinuity,” and that “Jeux lies at the crossroads of

a change in aesthetic values from the need for continuity to the desire to

create discontinuity.”

Levels of formal discontinuity in Jeux occur

as fragmentation, contrast, and stratification of materials, which depending on

the degree of contrast may or may not produce functional discontinuity,

while functional discontinuity results from the separation created by

the troughs between successive waves, moment-form tendencies, and

through process inhibition, interruption, change, deflection, and reversal,

wherein discontinuity is presented as a form of inhibited continuity.

Levels of formal continuity in Jeux occur in the form of repetition,

periodicity, metric regularity, gradation, consistent timbres, the linear

writing, and motivic connection and recurrence, while functional continuity

results from open-ended and directed wave processes. The dialectic of

continuity and discontinuity is sometimes highlighted, as for example through

the refraction of continuous wave motion between contrasting modules of

the mosaic. The general effect is one of connected blocks and contrasts wherein

successive modules are, to different degrees, “set off” from one another

through the timbral, textural, rhythmic, and motivic coherence within modules,

and the different degrees of change or discontinuity between modules. The

contrasts are always connected through motivic-thematic means and the

underlying wave process runs through the entire piece like a “mysterious

thread”

giving it flow and continuity.

Levels of

Design

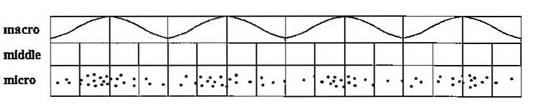

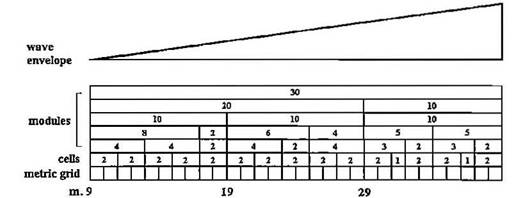

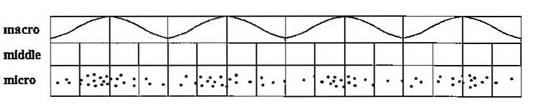

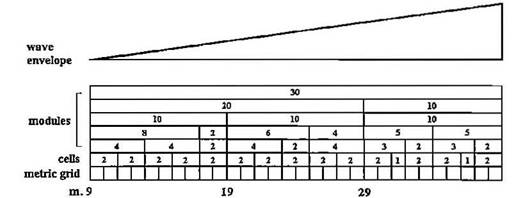

Debussy’s

composed-out musical waves have three general levels of design: (1) a micro

level which corresponds to the motivic-thematic particles, processes,

and melodic waves; (2) a middle level, which corresponds to the metric

grid, metric waves, and the mosaic structure; and (3) a macro-level,

which corresponds to the statistical waves, wave groups, and

larger sections. With the wave processes and mosaic structure being

synchronized by the metric grid, these three levels of design work together,

and integrate continuous and discontinuous elements. The basic relationship

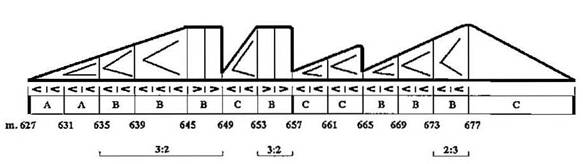

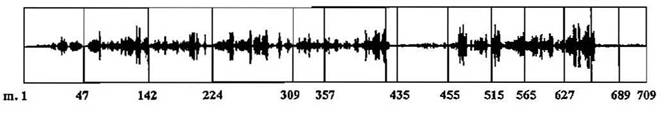

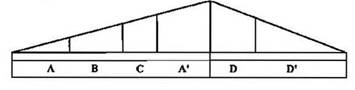

between these levels can be illustrated as follows (Figure 2). In Jeux

this basic idea is developed into elaborate patterns.

Figure 2:

Structural Levels of Wave Process

These

three levels are general levels of design. Each level can be further

subdivided and there is some overlap between them. However, the general order

of micro- to macro- applies. There are minimal building blocks at each level

which are combined to form larger units. The smallest building block at the

micro level is the single note, which combines to form motivic fragments and

motives. The smallest building block of the middle level of mosaic structure is

the cell, which combines to form modules and sections, and the smallest

building block of the macro-level is the single wave, which combines to form

wave groups, wave trains, and large-scale wave processes. A motive is often the

size of a mosaic cell, while a statistical wave is often composed of two or

more mosaic modules. Even though the elements of each of these levels may be

analyzed separately, in practice each higher level subsumes the lower levels,

i.e., the mosaic structure includes the motivic particles, and the statistical

waves include the mosaic structure and motivic particles.

Micro

Level: Motivic-Thematic Particles and Processes, Melodic Waves

The

motivic-thematic particles of Jeux are small, relatively self-contained,

and open-ended. These motives and fragments thereof form the building blocks of

the larger motivic-thematic process and structures, and are generated by an

additive and combinatorial process. The process is non-developmental and

‘inorganic’ in the traditional sense of gradual, linear transformation

and incorporates elements of continuity and discontinuity, process and object.

As process, the motives are continuous, step-wise, and wave-like, while as

objects they form the particles within the statistical waves and cyclic

processes.

Debussy’s

motivic particles are characterized by a kind of invariance under

transformation. Meyer says that “Debussy, too, chooses motivic constancy.”

Eimert refers to the “associative and motivic coherence of the melodic shapes (Gestalten,

figures) in the piece” and creates a “table of associations” to show the

connections between the different motivic-thematic shapes and a general “wave

pattern.”

Trezise presents the similar idea of “motivic constellations,” as does Wenk

with his concept of global form.

This coherence is facilitated by Debussy’s use of simple, universal, and

ubiquitous shapes, e.g., simple wave shapes, ascending and descending scale fragments.

Pasler refers to the idea of “a short, clearly recognizable motive that is

flexible and easy to manipulate.” Bergson’s “mean image,” and Barraqué’s

“thèmes-objets” similarly do not develop but recur, divide, and recombine in

ever-new ways

and Trezise comments on the same yet different quality of the motivic shapes,

referring to the “quest for motivic diversity as for motivic homogeneity” and

“the sensation that an idea is familiar, even when its surface bespeaks

disparity and incongruity.”

Debussy thus also creates less easily recognizable variations of

motivic-thematic ideas, hence the idea of transformation and so, in

keeping with Debussy’s aesthetics, the similarities between such motivic particles

are often ‘subtle’ or subconsciously perceived.

Within

the self-similarity of materials there is free variation of motivic design.

Debussy flexibly uses a number of variation techniques including inversion,

augmentation, diminution, reversion, interversion, change of tempo, rhythm, or

accent, thinning and filling of thematic shapes, and techniques similar to

liquidation, dissolution, condensation, and reduction. Sometimes melodies are “varied” by simply

doubling them with intervals or chords, similar to organum but Debussy’s

variations are largely based on arabesque techniques, including those from

Baroque ornamentation changes of articulation, simple embellishments such as

grace notes and trills, “free ornamentation” and melodic elaboration using

neighbor notes or intervals, filling of intervals, alternation with common

tones, micro-rhythmic variations, syncopation, etc. Debussy’s also generates “families” of

related motives through the use of secondary variations

- variations becoming the basis of further variations, and so on. He goes

further by creating a more radical motivic‑thematic transformation

through change of “character,” for example, the transformation of a legato

motive into a motoric rhythmic figure (m. 342 clarinet, m. 387 bassoon).

Motivic transformation also appears as an extended form of traditional change

of mode between diatonic and chromatic. This often involves semitonal

transformations from major to minor 2nd, major to minor 3rd,

and perfect 4th or 5th to tritone (or vice versa).

The motivic particles and arabesques form part of an overall alternation and

synthesis of diatonic and chromatic materials wherein motivic-thematic shapes

are composed from diatonic, modal, pentatonic, overtone (or acoustic), chromatic,

whole-tone, octatonic, and other symmetrical scales, or from an intersection

and combination of these, resulting in a

more exotic “chromatic modality.”

Even

though Debussy mentions Bach and Palestrina as examples of musical arabesque

and the “principle of ornament,” his method and aesthetic is also similar to

that of arabesque in Middle-Eastern music, from where the term ‘arabesque’

derives, and of Art Nouveau, both of which interested Debussy. These styles

share an emphasis on melodic linearity and embellishment. The use of

embellishment and ornament also provide an improvisation-like element of free

play within a structure. Al-Faruqi, in her description of arabesque in Arabian

music gives a description that perfectly fits Debussy’s technique:

...

a conjunct string of short motif or motif conglomerates in varied repetitions.

Each one of these chains of repeated or symmetrical combinations creating an

aural arabesque, a labyrinth journey of melodic and rhythmic details... towards

a musical resting place. ...Each phrase is a new excursion into a tonal or

durational unknown with its aesthetic tension, followed by an eventual

relaxation... to a point of musical stability.

The arabesque is “open-ended,” “capable of

accepting the addition of further motifs and modules. The arabesque is

experienced in parts, for “the significance of each motif and module must be

appreciated one by one, ...with its many mini-climaxes.”

The

open-ended quality, alternations of tension and relaxation, “mini-climaxes,”

and “point of musical stability” noted above are characteristics of the

‘continuous’ aspects of wave processes. At the same time, the combination of

motives, “motive conglomerates,” and chains of varied repetitions relate to the

additive or ‘discontinuous’ aspect of these designs. Debussy uses such additive

and combinatorial techniques, including repetition, transposition, division,

fragmentation, addition, subtraction, and permutation. His generative

process also connects the motivic particles at the micro level, creating

moment-to-moment continuity, ensuring that even contrasts are connected. The

connective elements or ‘subtle links’ consist of single pitches, intervals,

chords, fragments, or shapes.

Other connective devices include immediate transformation, embellishment,

overlapping, and change of function, or kinesthetic shift.

Connection is also achieved at the phrase level and sectional levels through

what Ruwet calls duplication, which involves using the same or varied

beginning, or ‘head’ of an idea as the basis for a successive variant, but with

a different ‘tail’ or ending.

Debussy also uses the opposite technique, that is, using the ‘tail’ of an idea

as the basis for the ‘head’ of a following idea, producing a ‘propagation’ or

transference of motives between modules or waves (e.g. mm. 27-31). The use of

repetition in the form of reiteration provides both cohesion and segregation,

both defining and dividing events, producing fragmentation. Reiteration (and

variation) also contributes to a focus on the moment through an emphasis

on differences.

The

qualities of continuity, flexibility, fluidity, and “curve” of melody which

Debussy defines as part of musical arabesque,

give the arabesques of Jeux the quality of melodic waves with

motivic particles arranged so as to create wave patterns, circularity, and

open-endedness. Eimert makes numerous references to the “motivic particles,”

“linear writing,” and “ornamental stepwise waves.”

Pomeroy notes that Debussy’s arabesques generally tend to fill registral space

with a “combination of stepwise and relatively undulating disjunct motion,” and

generally many of Debussy’s melodies have shapes described as undulating,

wavering, oscillating, etc.

Even though the motivic particles are small and frequently shift from one

instrument or group to another,

the continuity of arabesque and wave patterns are still at work.

The

motivic particles and melodic waves thus shape the larger textural and

statistical waves of Jeux. The melodic waves take the form of either the

more frequent, ornamental, and often rhythmic motivic waves, or of

simpler and more lyrical thematic waves. These two kinds of waves are

sometimes expressed as a play of rhythmic-motivic and lyrical ideas. Trezise

quotes Barraqué on a similar play of “rhythmically-oriented” and

“melodically-oriented” ideas in Jeux de vagues.

In contrast to the more common fragmentary and ornamental motivic waves, there

are few extended thematic statements or thematic waves in Jeux, and these

are more prominent in the second part of the piece. However, lyrical fragments

are found throughout the piece, often as secondary or background parts. There

is nearly always a melodic element in the music, whether it is arabesque‑like

or lyrical, and figuration is nearly ever‑present. Motives and themes are

composed through the same generative process and from the same pitch cells,

providing unity and allowing motives to be transformed into themes. Trezise

refers to “the transformation of arabesque into motif,’ and Eimert gives the

example of the “alpha” motive from m. 49 augmented into climactic theme at m.

677.

Another example is the transformation of the descending, chromatic, “beta”

motive from m. 10 into the thematic lines at mm. 475, 481, and 489. Motivic and

thematic ideas are also presented together, including the simultaneous, or heterophonic,

presentation of the same idea (e.g., m. 585 horns and m. 587 oboes)

where an idea emerges in both thematic and ornamental form, thus combining the

ideas of arabesque and heterophony (e.g., mm. 100-117, the flute part presented

ornamentally in the clarinet part). Moreover, Debussy often uses a more

generalized form of “heterophonic orchestration”

through slightly varied doublings of parts. The longer thematic waves of Jeux

have a joyful and flowing contour. The ‘waltz theme’ of Jeux (mm.

566-604) is parallel in function to the “smooth sailing” theme of Jeux de

vagues.

In

addition to the moment-to-moment connection between the motivic particles of the

arabesques and melodic waves produced by the generative process, there is also

a regeneration or recycling of particles that occurs between waves in

the form of returns and ‘return effects’

of motivic-thematic materials which recur, usually transformed. Debussy wrote

of the search for “forms in constant renewal.”

and renewal suggests cyclicity, as distinct from “constantly new forms.” Some

of these recurrences are found at apparently random positions within waves and

sections, leading some to refer to this as a “separation of theme from

structure.”

The cyclic nature of the wave process itself encourages such recycling, and

provides a format for Debussy’s tendency to reiterate and transform

motivic-thematic material. The constant recycling of numerous particles of

motivic-thematic materials also produces a static and nonlinear sense of

multiplicity and simultaneity.

Eimert says, “in the vegetative circulation of the form there is no

development”:

The

ornamental formations based on close intervals move in simple waves, which

circulate or are spun out, are repeated and give rise to fresh waves, a

circulation which is always at its goal and therefore never ‘going’ anywhere,

never building up thematic figures, with no motivic ‘working-out’. Instead of

this we find motivic association, which produces inexhaustible variants, not in

fixed thematic form, psychologically bracketed off, but in a freely growing

process of breeding.

Eimert’s

comments are somewhat overstated, his point being to emphasize an important

aspect of the motivic process. The incessant recycling of the motivic particles

creates an ever-presence of motivic-thematic materials submerging and emerging

from a static ‘background.’ This emphasis through reiteration and recurrence on

what Pasler calls the “essence” of a motivic idea creates a focus on the

moment similar to that of Eastern music, which is, as Koelreutter says, to

“circle round a central idea.”

However, Jeux expands this idea by using two basic germinal ideas which

are recycled, a modal “alpha” motive-theme (m. 49) and a chromatic “beta”

motive-theme (mm. 1-2). Most of the motivic-thematic designs are derived from

these basic ideas and their combination or synthesis.

In addition, a number of secondary motivic and rhythmic motives are recycled

throughout the piece.

Secondary materials are also transformed into primary materials.

Fragments of primary materials are also often transformed into secondary and

accompaniment material, creating arabesque‑like backgrounds and figurations.

Because of the fragmentary nature of the materials, the distinction between

figure and ground, or between primary and secondary parts is sometimes weak or

even non‑existent, resulting in passages of figuration or accompaniment

which are purely “textural” in effect.

The textural and background elements, figurations, secondary parts, and

accompaniment patterns are also subject to recycling. Purely textural passages

sometimes provide a lull or break from the focus of the motivic-thematic

process (e.g., mm. 130-137, at the end of the first section). Eimert’s

discussion of “ornaments, motives and flocculi, which have a secret associative

power”

suggests that these background and secondary parts also follow the “principle

of ornament.” The manner in which Debussy transforms the motivic-thematic

identities themselves does not differ from traditional music. Rather, it is the

ornamental design of the motivic particles and the manner in which they are

combined which differs.

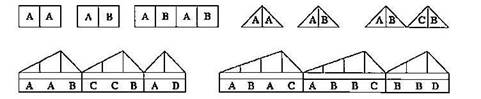

The

recycled materials have different degrees of connection between waves. There

are, generally speaking, three basic levels of recurrence of motivic‑thematic

materials in Jeux. The first is within sections, that is, between

successive waves or through returns after contrasting materials, e.g., AA, AAA,

ABA, ABAB, and involves materials returning in literal or varied form. The

second level is between sections, e.g., ABCB ADED BFGF BHIH, with materials

returning at the beginning of each section, and involves a return of materials

usually transformed, e.g., the “alpha” and “beta” themes return transformed

marking the beginning of different sections. This technique resembles that used

between movements in cyclic forms, except that here the returns occur between

sections and more than one theme is used, although the “alpha” theme is more

central.

The use of two basic themes instead of one vastly expands the formal

possibilities. Out of the twelve sections into which Jeux is analyzed

below, seven begin with some form of the “alpha” theme, while five begin with

some form of the “beta” theme.

In addition, the “alpha” and “beta” materials are freely developed and

alternated within these sections. The third level of returns is large-scale,

between the large parts of the piece, as in the reprise and epilog (postlude)

of Jeux, and are usually literal. More literal returns create a greater

sense of stability and closure, as with sectional and large-scale returns,

which often form ABA patterns. Short-scale recurrences define sections while large-scale

recurrences define the entire piece.

There

is a kind of cyclic development or “working out” of motivic-thematic material

within the piece which consists of a gradual departure from the original form

of the “alpha” motive during the first two sections of the piece, where it

appears in more literal and varied forms, followed by a greater use of the

“beta” theme and more derivative forms of the “alpha” theme during the

following sections of the first part of the piece. This helps give the literal return

of the “alpha” motive at the reprise (m. 455) a strong sense of return,

pointing back to the beginning of the piece, and creating large-scale

structure. The second part of the piece beginning at the reprise forms a

further cycle of motivic-thematic development which further integrates and

brings together elements from the first part. This involves the increased use

of literal rather than transformed versions of the “alpha” theme, helping to

integrate and resolve the motivic process toward the end of the piece. Finally,

the literal return of material in the epilog (postlude) points back to the very

beginning and closes the piece. The effect of “departing” from original motivic

forms is due to the anchoring effect of their initial presentations along with

the different degrees of transformation these undergo within the larger

processes. Structurally, the original forms and their recurrences are generally

more ‘stable,’ while their transformed versions are more ‘unstable’. The

original presentation of the chromatic or “beta” motive is also less

rhythmically defined than that of the “alpha” motive, and lends itself to more

fluid transformations and adaptations.

In

addition to the cyclic regeneration and development of materials, there are

several other developmental motivic-thematic processes in Jeux which

differ from traditional procedures. For example, the piece begins with

fragmentary motivic ‘seeds’ or germinal materials that combine and develop as

the piece unfolds, giving a sense of growth.

As the piece unfolds, original, transformed, and new ideas mix together.

Trezise refers to Debussy’s technique as “a procedure of development in which

the notions of exposition and development co-exist in an uninterrupted stream,

permitting the work to be propelled along by itself without recourse to any

pre-established model.”

Leading up to the final climax of the piece there is a use of shorter and

shorter alternation, interaction, and integration of motivic materials (mm.

627-676). Moreover, as Kinariwala says of Debussy, “The succession of ideas

does not always lead to an inevitable goal but is often subjected to

interruptions and circular patterns,” and that “Debussy’s structures at higher

levels progresses not through a linear development but through one made up of

starts and stops, returns and contrasts, seemingly without order or direction

but always connected through the continual process of generation.”

In Jeux, these motivic-thematic processes work within the larger

statistical wave process.

Middle

Level: Metric Grid, Metric Waves, and Mosaic Structure

The

flow of waves in Jeux is “rhythmicized.” This occurs of course through

the rational rhythms, and through the mosaic structure itself. The nearly constant

3/8 meter provides measure, continuity, and periodicity, and forms a ground

upon which a play of rhythmic patterns can unfold, i.e., recurring 3/8 rhythms,

cross-rhythmic patterns, hemiolas, waltz patterns, two-measure patterns

producing a 6/8 feel, etc. The regular meter forms a metric grid, and

provides a foundation and underlying continuity for the mosaic structure and

larger wave processes. The piece is also governed by a “reference pulse” which

is part of the temporal foundation of the piece. This is the Tempo initial

of m. 9 (dotted quarter note = 72 M.M.), which returns regularly with the

marking Mouvement initial. Pasler considers this an important

organizational aspect, as well as Boulez, who believes that “a single basic

tempo is need in order to regulate the evolution of thematic ideas.”

Boulez thus sees continuity as prevailing in Jeux. Moreover, the pulse

is not mechanical. Eimert likens the fluctuating tempo, rubato, and

statistical wave process of Jeux to breathing, as a “respiratory flux of

movements.” Pasler likewise compares the tempo fluctuations to a heartbeat,

“accelerating and decelerating depending on the context.”

These tempo fluctuations are coordinated with the statistical waves and even

though the mosaic structure is composed of discrete parts, these features

provide it with temporal regularity and an elastic quality.

The

regularity of pulse and meter create periodicity. This is, of course,

felt more or less depending on the strength of its musical articulation.

Natural waves are also characterized by periodicity. In Jeux, the

periodicity of pulse and meter creates metric waves, with the strongest

being at the basic metric level, which Zuckerkandl calls the ‘principle wave.’

The metric wave has an inverse climax function in that the downbeat or trough

is stronger than the crest or upbeat portion of the metric pattern or wave. The

principal or basic metric wave interlocks with the metric grid and the mosaic

cells, and combines to form larger nested metric waves corresponding to mosaic

modules and statistical waves. Zuckerkandl states that “the meter in a piece of

music does not beat simply in a single wave but in a complex involving

superordinate and subordinate waves, of which at least the two closest to the

principal wave can be felt distinctly,”

making the periodicity most immediate at the metric and middle levels. The

intensification phase of a wave can be seen to form a large ‘upbeat’ in

relation to the ‘downbeat’ at the climax of the wave, or vice versa. In Jeux,

this gives rise to interplays between the downbeats of wave climaxes and the

structural downbeats of sections. Debussy also uses syncopation, cross-rhythms,

and hemiolas to increase forward-drive towards the downbeat at the crest or

climax of the wave, followed by rhythmic regularity (or vice versa) and

de-intensification. Small repeated wave shapes and ostinati are often

coordinated with the metric wave. Examples are the undulating strings of the

opening of La Mer and later ostinati (mm. 31-42, 105-121).

Another

feature of the wave process is momentum. Momentum may vary in strength,

and results from periodicity, the irregular 3/8 meter, which is

self-propelling, and rhythmic and wave processes which produce intensification,

forward drive, and a structural accumulation of energy. Zuckerkandl

makes reference to momentum and the cumulative effect of periodicity while

discussing the polarity and intensification of wave processes, saying that “The

swing that makes the wave reach its crest at the same time carries it beyond

its crest, toward a new cycle, a new crest” and that “the repetition of the

same metrical wave now produces intensification. Every new wave, in

comparison to the similar wave that preceded it, is experienced as an

increase.” The periodicity works at the middle level of

the metric wave and the macro-level of the statistical wave and momentum

increases as the wave crest is approached.

Together, the basic tempo, metric grid, and associated features of periodicity

and momentum form the temporal basis of the mosaic structure and wave process.

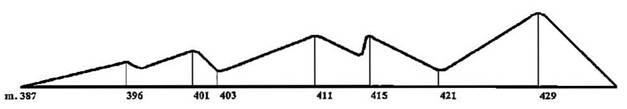

Figure 3

Coordination of Tempo Fluctuations, Metric Wave, and Statistical Wave

The

mosaic structure is made up of three kinds of units: cells, modules,and

sections.

Cells form the smallest units of

1-2 measures in length, often coinciding with motives, and interlocking

with the metric grid. The concept of a cell is different from that of a

motive in that a cell consists of a measured unit which is interlocked with the

metric grid. In distinction, a motive is usually a smaller, metrically

independent, and monophonic part. In addition, mosaic cells originate at the

middle level and form the building blocks of the mosaic structure, whereas

motives originate at the micro level from single notes. Cells thus bring

motives into the metric context and mosaic structure. The motivic-thematic

material is subsumed within the mosaic cells, and gives each cell or module its

identity.

The

timbral-textural definition of the mosaic units is also important, and because Jeux

uses an orchestra, a cell consists of a textural unit of several

interlocking parts. These cells usually consist of a main part and a secondary

part or parts which are in simple homo-rhythmic, contra-rhythmic, or hetero-rhythmic

relationship to each other.

Modules are made up of cells, usually two to eight or more, correspond

in size with waves or parts thereof, and form the basic functional units of the

mosaic. There may be several levels of modules (see Figure 7). Sections

are made up of modules, forming ABAB, etc. patterns which are relatively

self-contained. The modules which make up sections are often defined through

the juxtaposition and alternation of diatonic and chromatic materials which

they contain.

At the highest level the mosaic corresponds to the complete structure,

with its sections and constituent modules and cells. In addition to the linear,

additive aspect of mosaic units, there is also an occasional superimposition

or layering of parts within cells and modules. Wenk notes that in Jeux “Debussy

frequently splits the individual unit into two or more layers, producing a

horizontal as well as a vertical fragmentation of the musical texture.”

This occurs to different degrees, ranging from the simple superimposition of

rhythmically regular and interlocking parts, to a heterophonic or polyrhythmic

layering of regular parts (e.g., mm. 130-137), to the layering of more

irregular parts. Because of the gamelan influence on Debussy, the parts

sometimes contain heterophonic, interlocking, or hocket-like elements.

The

mosaic structure is produced through an additive and sequential process. Cells

are generally repeated to form modules while modules are usually contrasted and

have a greater sense of juxtaposition. The repetition of cells has a

form-building function which provides coherence and structural redundancy and

allows cells to group into modules through similarity.

Pomeroy gives a description of Debussy’s use of mosaic structure, its

integration of motivic-thematic ideas, and its construction:

Debussy

integrates such thematic ideas into larger formal sections via a characteristic

technique whereby arabesque-like units, typically two bars in length, are

combined through a chain-like process. This constructive technique is so

prevalent as to constitute one of his most readily identifiable stylistic

traits. The units’ identity as such is established by symmetrically balanced

contrast and juxtaposition in factors such as motive, texture, and harmonic rhythm

(also, of course, secondary parameters of instrumentation, dynamics and so

forth); larger form is generated by the hierarchical chaining of units and

their compounds.

The

contrast between modules is a matter of degree and ranges from mild to relatively

strong. Debussy increases the sense of juxtaposition through the use of

interpolation, stratification, and moment-form tendencies. Moreover, the

juxtaposition of homogenous elements is more common than that of heterogenous

elements. Shattuck states that the juxtaposition of homogenous or similar

elements creates an “illusion of smoothness and rhetorical progression” which

however “rapidly disintegrates.” Shattuck adds that “By their very

repetitiveness the parts establish their independence” and that “style here

becomes circularity, a distortion of linear development and direction in the

traditional sense.”

On the other hand, the juxtaposition of heterogenous elements interrupts linear

development. Furthermore, the additive and combinatorial aspect of mosaic

structure is similar to that of arabesque, consisting of small units which are

repeated and combined (or “woven”) into larger patterns. Motives are thus to

melodic waves what modules are to statistical waves. However, musical arabesque

emphasizes the elements of similarity and continuity, while mosaic structure,

as inspired by visual mosaic, emphasizes the spatial, discontinuous, and

open-ended elements.

This difference forms part of the duality of continuity and discontinuity in Jeux,

i.e., the micro and macro-levels are continuous while the middle level is

discontinuous.

Mosaic

modules are combined according to the law of symmetry, which is applied

as a sense of balance, complementation, and equilibrium. This results in

techniques including repetition, binary constructs (antecedent - consequent,

statement - counterstatement), and complementation (intensification and

de-intensification, contrast, Al-Faruqi’s ‘symmetry’). An example is Debussy’s

common practice of repeating once and moving on, e.g., (AA) (BB) (CC) (DD) etc.

Debussy takes this process a step further by repeating groups of modules, e.g.,

(AB AB) (CD CD) or (ABC ABC) (DEF DEF) or (ABCD ABCD) (EFGH EFGH) and even

(ABCDE ABCDE) (i.e., mm. 224-244, 245-263). This method is used commonly in Jeux,

and results in a chain of relatively self-contained sections. A group of

modules is repeated, forming a section, followed by a different group of

modules, forming a new section, and so on. Although the sections may seem

loosely connected, they form part of a large-scale process in the piece.

However, mosaic structure works mostly at middle levels of the formal hierarchy

in the form of modules and sections.

Sections do not tend to combine to form larger sections, except for some

contiguous sections that form free duplications (or replications) of each

other. This aspect of the mosaic structure relates to Boulez’s comment on Jeux

having a ‘woven form.’

Moreover, even though the mosaic structure is focused on the middle level,

there are large-scale proportions, including the use of the golden section.

The

contrasts and alternations of modules in the above forms of repetition, e.g.,

ABAB, produce returns, interpolation, and stratification of

materials. The return or recurrence of materials after an intervening contrast

emphasizes similarity and provides structural definition to the mosaic

structure.

The law of symmetry also expresses itself here as the law of return,

in both repeated (ABAB) or ternary (ABA) organizations, and contributes to a

cyclic effect and closure. Interpolation involves the temporary

interruption and alternation with a secondary process, whereas Cone’s sense of

stratification involves a more sustained alternation of processes. Cone’s

concept of ‘interlock’ of strata, results from the resumption of an interrupted

or suspended process after an intervening contrast

corresponding to the cinematographic technique of “cross-cutting.” Debussy

employs stratification to some extent in Jeux, in the form of

overlapping stratification (or dovetailing) between sections (e.g., mm.

284-308), but more commonly in the simpler and short-scale form which

Kinariwala calls “interlock through interpolation.”

An example of duplication within mosaic structure is the open

repetition pattern of ABAB’, where B’ is open,

or AABA’,

which creates a functional open-endedness and passive continuation.

Debussy also uses closed repetition, e.g., AA or ABAB, which, due to its

formal closure and self-containment, leads to a focus on the moment. Modules

are also combined according to Ruwet’s “dialectic of the repeated and the

non-repeated” or of the “expected and unexpected,” e.g., AAAB or ABAC. In

addition, the interaction of duple and ternary groupings sometimes produces a

blurring of structural boundaries

and alternate interpretations and as to modular groupings, e.g., (ABA BCBC) vs

(ABAB BCBC) or (ABAB CBCB).

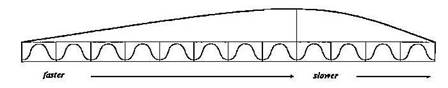

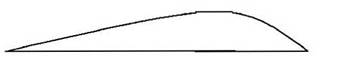

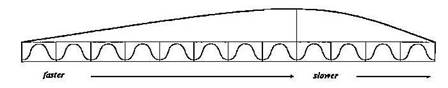

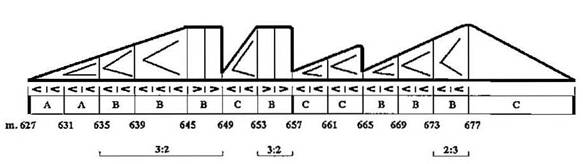

Debussy’s

mosaic structure evolved from simple block-like modules with steady intensity

levels to modules with increasing and decreasing intensity levels

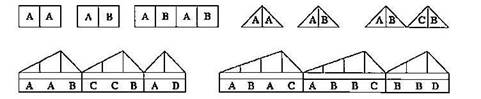

corresponding to the parts of a wave. Figure 4 shows the basic idea of modular

structure, from simple blocks to parts of waves, represented by the triangular

modules, e.g., intensifications only, intensifications and de-intensifications

in stages. Block modules can also represent standing waves, which are of

relatively steady intensity. Other modules within the mosaic structure serve as

transitions or bridges.

Through

the complementation and symmetry of intensification and de-intensification

phases of waves, Debussy discovered a new and powerful method of coherence and

continuity between successive modules of the mosaic structure. The alternating

phases of waves produce a corresponding open-closed functionality which links

modules into pairs through complementation and symmetry, whereas returns of

modules help define sections. The mosaic structure incorporates further

rhythmic elements which relate to the wave process, including static and

dynamic symmetries, a “play of symmetries and asymmetries,” irregular

groupings, imbalance, and forward drive. Debussy’s basic repeat patterns are

duple and square, 2+2 = 4, 4+4 = 8 measures, etc. This is made more interesting

in several ways.

One method is the setting up of regular repeated patterns of cells or modules

which are shortened, e.g., (4+4)+(4+2), 4+3, or 4+4+3+3, 4+2+2+1+1+1+1, a

process which reinforces the intensification phases of waves. Often the

successive shortening or truncation of a repetition is used to reinforce the

intensification phase of a wave, the build-up of energy, momentum, and forward

drive towards the climax or release (e.g., mm. 639-644 form a (2+2)+2 or 4+2

pattern). As a way of shifting the duple predominance, sometimes there is a

play of 2s and 3s, that is, the repetitions in the modular mosaic become part

of rhythmic play of patterns which are set up and varied. These apply to the

cellular and modular construction and in addition to the techniques already

mentioned of syncopation, cross-rhythm and hemiola used within the metric wave.

Figure 4: Evolution

of Mosaic Structure

The

mosaic structure has an open-ended quality which is produced through

different means. Its combinatorial and permutational construction has appealed

to the ‘serial’ and open-form

sensibilities of later composers, wherein mosaic units can be re-combined and

added indefinitely and the modular juxtaposition and fragmentation of materials

produces a sense of discontinuity and inconclusiveness. Other means of producing open-endedness are

the use of passive continuation and non-functional harmony and

symmetrical scales. Howat also refers to the “enigmatic mixture of closed and

open-ended formal characteristics”

in relation to the fact that the mosaic units are formally relatively

self-contained yet functionally open. Together with elements of discontinuity

and lack of hierarchy, the non-functional and static elements often give the

mosaic structure qualities of moment-form. Kramer notes how Messiaen

took the mosaic technique of Debussy and Stravinsky closer to moment-form and

Stockhausen’s further development of the idea. Kramer uses the term sectionalized

collages as synonymous with moment-forms. However, Debussy’s mosaic

modules are smaller than collage blocks, and are connected through his ‘subtle

links,’ and form a mosaic of connected lines rather than a collage of

contrasts.

The

additive and combinatorial aspect of the mosaic structure lacks organic

development, and instead produces a static sense of juxtaposition and

simultaneity. Evans says of mosaic structure that “the impression of

simultaneity of the whole is achieved through a collection of seemingly

constantly present shapes that may intensify or vary independently without

affecting an overall progression towards an end.” She also suggests that even

though mosaic structure consists of an inorganic and “non-progressive development,”

other kinds of processes and “development” are possible within the mosaic

structure, e.g. processes of repetition, permutation, variation, ornamentation,

fragmentation, extension, expansion, interruption, abbreviation, recombination,

stratification, different rates of change, and intensification and

de-intensification of materials. The “non-progressive development” of the

mosaic structure leads to a sense of simultaneity and a focus on the moment.

“Lack of overall development seems to be an essential feature of the mosaic

model; it is perhaps the most crucial way of depicting a sense of’ ‘now’.”

Debussy

combines the elements of discontinuity and open-endedness of the mosaic

structure with the continuity of the motivic-thematic and statistical wave processes.

There is a kind of development within the mosaic structure of Jeux

whereby Debussy first uses larger modules, then parts of modules, and then

sub-parts of modules, these corresponding to complete waves, then the

intensification and de-intensification phases within waves, and then stages

within these phases. This all becomes part of an increasingly elaborate play of

repetition, variation, and alternation of modules which is particularly notable

within the first part of the piece.

Moreover, the wave process not only provides an underlying continuity but also

shapes the entire piece. The wave process provides a continuity and flow which

underlies and unifies the successive modules, including repetitions, contrasts,

alternations, returns, and which can be distinguished from the block-like

contrasts exploited by Stravinsky. Debussy’s use of mosaic structure in Jeux

is unique. His modular waves may well have been his response to Stravinsky’s

block-like structures, and an ingenious implementation of the “dialectic of

continuity and discontinuity.”

Macro-Level:

Statistical Waves

The

principles of flexibility, fluidity, ornament, and the natural curve which

Debussy mentions are also present in the textural waves of Jeux.

Debussy’s statement that musical arabesque is “subject to laws of beauty

inscribed in the movements of Nature herself”

makes an implicit connection between musical waves and natural waves, of

“sinuous arabesque based on natural forms.”

This description includes Eimerts’s “vegetative forms”, the sinuous vines of

Art Nouveau arabesques, with their leaves of different sizes and similar

shapes, and what he calls“vegetative inexactness” and the

“ornamental-vegetative formal principle” in Jeux.

However, although the ballet story certainly suggests back and forth motions,

Debussy was not trying to portray natural waves in Jeux. Instead, he plays with a more abstract

sense or “essence” of wave behavior. Debussy says “I wanted music to have a

freedom that she perhaps has more than any other art, as it is not restricted

to a more or less exact reproduction of nature, but instead deals with the

mysterious correspondences between Nature and the Imagination.”

Debussy expresses his admiration of “the music of nature,”

and states that “It is the musicians alone who have the privilege of being able

to convey all the poetry of night and day, of earth and sky. Only they can

re-create Nature’s atmosphere and give rhythm to her heaving breast.”

However, Debussy stresses that “there is no attempt at direct imitation, but

rather at capturing the invisible sentiments of nature.” Trezise refers

to this as a “synthesis of the natural world and human emotion.”

A reference to “capturing the invisible sentiments of nature” or the synthesis

of nature and human emotion is seen in Debussy’s comment that the orchestration

of La Mer “ is as stormy and

varied... as the sea!.”

Potter also writes of musical onomatopoeia in reference to “a multitude

of water figurations” that “evoke the sensation of the swaying movement of

waves and suggest the pitter-patter of falling droplets of spray” in La Mer.

The elements of process, flow, and the “free play of sound” enter in the

temporal dimension of these comparisons with nature.

Debussy’s

“correspondences between Nature and the Imagination” are a form of analogy.

The word analogy refers to the comparison of things that are different

but which show similarity in some respect, though not necessarily in others.

The idea of representation is similar though more specific, what Debussy

called “reproduction of nature.” For example, a painting of an object is not

the object, a graph of a wave is not a wave, music notation is not music, but

these are understood as representations or analogues. In the same way, composed-out

musical “waves” can represent or, more abstractly, be analogous to natural

waves. Trezise states that “Debussy did not believe in absolute music, but he

also mistrusted portraiture, so his works lie midway between, encouraging

neither abstract analysis nor straightforward story telling.”

Waves are universal and natural shapes and processes which have been

scientifically studied and codified, and relate to what Debussy called “the

laws of beauty inscribed on the movements of Nature.” It is therefore useful to

apply the language of waves, including descriptions and terms from physics,

oceanography, and other fields, in order to draw “correspondences” or analogies

with the waves of Jeux.

Debussy may not have used such technical terms, but we do know of his interest

in the natural subjects of water, rain, and the sea

and these terms have a great power in their ability to illuminate the

connection between natural waves and musical waves.

A

wave is generally defined as a disturbance that is propagated through a medium,

as an increase and decrease, a rising and falling, back and forth, or

oscillatory motion around a point of equilibrium, as an undulating curve,

sinuous motion, etc., which is generally characterized by continuity,

gradation, and flow. In addition, waves are described in terms of their

structural features, or according to their type, for example different types of

ocean waves. Different kinds of waves behave similarly no matter what the

medium of propagation. By analogy, the medium of sound is air, while the medium

of music is sound. In nature, physical energies shape material mediums such as

air and water, while in music human creative energy shapes the medium of sound.

The resulting shapes and forms, in this case composed-out waves, are in turn

transmitted to the listener through the medium of air, in the form of sound

waves. The comparison is figurative. Sound as a medium for music is a virtual

medium, not physically manifest as is air or water, but projected through the

music itself. In addition, natural mediums are composed of material particles

such as atoms, molecules, water drops, etc., while in music, the particles

consist of notes and motives.

Of course, these musical particles can be further divided into basic dimensions

of timbre, pitch, duration, etc.

The

musical particles in Jeux form part of larger textures and statistical

waves, though not all statistical waves form “statistical textures.”

It is also possible to distinguish between statistical waves which form “statistical

textures” or which are characterized by figuration, from those that are

basically “arranged” forms of melodic waves.

Furthermore, the texture moves between these different kinds of waves. All of

these waves are perceived as larger forms, or gestalts, made up of parts

and particles. Although the particles make up the waves, the waves behave like

energy fields within which the particles are organized. This is according to

the gestalt field concept, which states that a whole and its parts

mutually determining each other’s characteristics.

Eimert notes the textural waves of Jeux, pointing to the

“quasi-statistical accumulation of sound” and “the build-up and alternating

play of piled-up groups of sound.” Eimert adds that these statistical waves

“result from the closest interweaving of all categories of form,” and that “the

categories of form take part all with equal weight in the wave-movement.”

Pasler refers to the play of balance, counterbalance, and equilibrium which is part

of the wave process, stating that “this succession of impulses and tensions-

which can be conjunct or disjunct- keeps the form fluid. Balance or equilibrium

is constantly being recreated.” She quotes Grisey on “music as the organization

of “tensions” moving in waves of contraction and expansion” and Stravinsky on

“the drawing together and separation of poles of attraction.” Pasler also

suggests that “In Jeux, “arabesque” might apply to the play between the

various sections of music. Each section develops its own vector, its own force

of contrasting shape and direction, which needs resolution or balance.”

These statements sound like those by Al-Faruqi above, and further imply, as

Eimert does, that in Jeux the wave-like principle of arabesque is

extended to form textural arabesques. Eimert refers to these forms

simply as waves, or as “waves of time,” “envelope-curves,” and

“movement-curves.”

In

contrast to the surface motivic-thematic and timbral level, statistical

processes function at an underlying or more ‘subtle’ level, and can be thought

of as independent from the surface level. Eimert refers to the underlying

continuity produced by this ‘invisible’ process, stating that “ever-different

elements appear within the same unitary wave-movement,” and that “It is as if

charged by a current, with constant tension in its elastic brilliance, whose

most wonderful quality is an unchanging vibration. The hidden impetus of the

current creates a new organic coherence, that of flowing form.”

The “hidden impetus” that Eimert mentions forms one of Debussy’s ‘subtle links’

at a statistical level of form and creates a new kind of continuity. Eimert

mentions how the wave energy gives continuity to the mosaic structure,

describing it as “an ornamental kinetic form which makes the cellular plan and

line-by-line structure of the four-bar phrases so supple that they can freely

follow the vibration of the form and can themselves become flexible form.”

Howat similarly says that there is “a very definable system of block

construction underlying the apparent fluidity of Debussy’s forms.”

The

energy of these waves is a quantitative and statistical factor corresponding to

the overall density, dynamics, or intensity of the waves. This overall intensity

dimension is composed of statistical parameters including attack density,

vertical density, loudness, and pitch height in the case of melodic waves.

In Debussy’s waves the separate parameters thus form parametrical waves

which move in a synchronized manner to create cycles of intensification

followed by de-intensification. The intensification and de-intensification

phases also occur in stages. Eimert says, “Dynamic evolutions and gradations in

Jeux are indicated not only by crescendo and decrescendo, but are

equally manifest in the changing intensity of the sound-mass resulting from

addition or subtraction of groups of sound - a process which is developed to

its highest degree of subtlety in the course of the work”.

The wave phenomena thus largely result from a sophisticated interplay of

intensification and de-intensification, or disturbing and restoring forces

which are governed by the larger principle of balance and equilibrium. Pasler

refers to this process as the “constant creation of a new balance.”

Waves thus include features of symmetry and asymmetry, ying-yang,

polarities, balance of opposites, growth and decay, antecedent-consequent, and

thesis-antithesis. The following table summarizes common means through which

the intensity dimension works (Figure 5).

|

|

Pitch

|

Dynamics

|

Duration

|

Texture

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intensification

|

ascent

|

Increase

in loudness

|

shortening,

|

increase

in

|

|

|

|

|

repetition

|

vertical

or horizontal density

|

|

|

|

contrary

motion

|

cross-rhythms

|

|

|

|

|

dissonance

|

|

|

|

De-intensification

|

descent

|

decrease

in loudness

|

lengthening

|

decrease

in horizontal or

|

|

|

|

slowing

|

|

vertical

density

|

Figure 2:

Intensification/De-intensification Parameters in Wave Processes

The

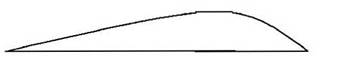

intensification and de-intensification processes give waves their

characteristic overall shape or envelope, consisting of a rise and fall,

or increase and decrease, the prototypical shape being that of a sine wave,

though there are other shapes (triangle, square, sawtooth, etc.). In natural

waves, the shape results from the displacement of particles within the medium.

In a transverse wave, particles are displaced perpendicularly to the

plane of motion. In music, this corresponds to the pitch contour of melodic

waves, where the particles or notes move up and down in pitch,

perpendicular to the plane of motion of time.

In a longitudinal wave, particles are displaced parallel to the plane of

motion, in a compression and rarefaction of particles. In music, this would

correspond to the statistical aspect of the waves, wherein the average

density of particles or notes, or intensity, increases and decreases over time,

producing an overall shape. Surface waves (or complex waves) combine

qualities of both transverse and longitudinal waves, the particles moving both

perpendicular and parallel to the plane of motion. The textural waves of Jeux

achieve this by combining melodic and statistical elements. Moreover, it is the

“curve” or envelope of these waves that matters (Eimert’s“ envelope curves”).

These “curves” are characterized by flow, continuity, cyclicity, and an

ornamental and playful quality or “jeu,” a continuous flux which is

connected at micro- and macro-levels through corresponding motivic-thematic and

statistical wave processes. The ‘invisible’ energy of the statistical waves

behaves as though independent of the motivic-thematic material or particles, as

in Eimert’s description that “ever-different elements appear within the same

unitary wave-movement.” Debussy seems to be aware of this, not only through his

use of motivic recycling at the micro level, independence of particle and wave

and of theme from structure, but in its most obvious form as refraction. Moreover,

according to the field concept, the energy of the waves dominates the

particles. The rise and fall or intensification and de-intensification phases

of a wave also complement each other as two symmetrical parts of a larger unit

and give waves coherence and closure. There is also the gestalt principle that

states that the parts of a form, in this case the intensification and

de-intensification phases of a wave, have different structural values, and that

some parts of the whole are indispensable if wholeness is to be retained while

others may be relatively unnecessary. This explains why a single rise or a

single fall may by itself qualify as wave-like without actually completing a

wave.

The

intensification phase of a wave leads to the crest or high-point of the

wave, which usually coincides with the climax

and the beginning of the de-intensification phase. In the case of a

plunging breaker the climax occurs at the low-point, forming an inverse

climax,

which reverses the functional polarity of the wave and the position of the

climax in relation to the crest. This typically occurs when a melodic line

descends from a crest, or de-intensifies, while other (statistical) musical

parameters, e.g., tempo, vertical density, and loudness intensify, leading to a

climax at a low-point of the wave. This also explains Debussy’s use of contrary

motion of melodic lines in approach to the climax of a wave.

A climax can also be delayed to some point after the crest yet still

within the de-intensification. Climaxes can be of different intensities

(amplitudes), or they can be attenuated (inhibited, damped,

anti-climactic) or non-attenuated. Waves can also release energy

gradually or suddenly, as in non-breaking and breaking waves.

Breakers are classified as spilling breakers, which break up gradually

and over a distance, plunging breakers, which curl over and break with a

crash, the plunge point being the point at which the wave breaks, and surging

breakers, which instead of spilling or plunging, surge up onto and break on

the beach face. Another classification is collapsing breakers. In

practice, these different types overlap.

Toch

mentions the wind-up as a means for gathering momentum at the beginning

of a wave, and initiating the build-up toward the crest, stating that,

melodically, this character is “produced by a group of short, quick notes,

anything from a turn (mordent) to an independent, characteristic motif” and

that “the “winding up” motion is then followed by the “throw” or “jump,” which

in turn is followed by a stepwise retrocession.”

This applies to the “alpha” motive (Example 1). The idea of a wind-up is also

accomplished through the statistical waves, where it is often present as the

first stage of two or more in the intensification phase of a wave, but which is

most noticeable in those instances of functional waves that set a new

wave or section in motion, notably at the beginning of wave trains or wave

groups (e.g. mm. 357-358, 395-396).

Example 1 “Alpha”

motive from Jeux m. 49 in clarinet

The

trough is the low-point between successive waves, and ordinarily a point

of relative cadence and repose.

Both the climax and the trough may consist of an instantaneous point, including

an elision point where the end of one process coincides with the beginning of

the next process, or they may be extended.

The crests and troughs of waves are points at which there is a process

reversal

between intensification and de-intensification, or progression and recession,

and vice versa, and hence a change of direction which is manifested as

the cyclic back and forth wave motion. The trough is sometimes also used as an ambiguous

transitional area in the shift or change of direction of the musical process.

Moreover, both crests and troughs relate to expectations as to whether or not,

or how a wave will climax or continue. Pasler says that “The anticipation

aroused by this music is not one of what will recur - what melody or harmony -

but a sense of what quality of sound and rhythm will provide counterbalance.”

The

intensification and de-intensification phases form complementary parts of a

wave. Schweitzer defines a motion-completion unit as made of two parts

consisting of motion, as drive, tension, and directional sense, followed

by completion, as goal, relaxation, and completion relative to its

preceding material.

This corresponds to Al-Faruqi’s concept of symmetry between modules, as

“a pair of design entities which are in some aspect balanced opposites or

reciprocals of each other.”

The resulting wave shape and complementation creates a self-containment which

is in contrast to traditional functional and linear processes, and contributes

to the moment-form qualities of many of the waves and sections.

Composed-out waves found in traditional music are usually part of a linear and

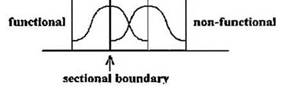

functional process. A functional wave has a defining function in that an

intensification phase leads to a new section, with the crest of the wave

coinciding with the structural downbeat of the section, and serving to set the

new section in motion (similar to the idea of a wind up). The new section often

stands apart from the wave leading up to it and consists of sustained activity

rather than a de-intensification.

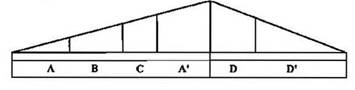

In contrast, Debussy’s non-functional waves are relatively self-defined

and self-contained, with the beginning of a non-functional wave usually

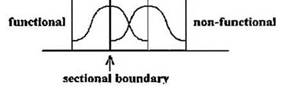

coinciding with the beginning of a section. Figure 6 illustrates the difference

between these two types of waves.

Figure 6:

Functional and non-functional waves

Most

of the waves in Jeux are non-functional. There are a few functional waves

whose function is similar to those of traditional music, that is, of leading to

a new section, sometimes in the form of a transition or of a wind-up. Because

the non-functional waves are relatively closed or self-contained and

succeed each other in an additive fashion, the formal process is also

relatively open-ended, like that of mosaic structure, wherein waves and

modules can be added indefinitely. A further level of interplay between

functional and non-functional waves is introduced through the use of the

inverse climax function. This allows the momentum and release at the inverse

climax point to set a new module or section in motion (e.g., mm. 469-472

leading to m. 473) or, alternatively, for the non-climactic crest of a wave to

form the beginning of a new section (e.g., m. 224). Moreover, the predominance

of non-functional waves places emphasis on statistical rather than syntactic

factors as formative.

Standing waves, or stationary

waves, are characterized by a relatively stable and symmetrical shape, an

oscillatory motion around a fixed reference point without achieving a

progressive movement or shape, of which there are a number of examples in Jeux.

The non-progressive character of these waves also contributes a non-functional

quality. Standing waves may also result from interference patterns between

waves, e.g., as with independent parametrical waves. This occurs to an

extent in Jeux through the inhibition of waves and inverse climaxes. A

standing wave may also gradually change into a progressive way or vice versa. Progressive

waves are characterized by an asymmetrical shape, having a longer

intensification than a de-intensification, mounting size and/or increasing

speed and momentum, forward motion, directionality, and may or may not break.

Progressive waves are also often associated with wave trains leading to a

cumulative climax. Deep water waves contrast to the typical breakers of

the relatively shallow surf. The effect of these waves is created

through a slower undulating motion and a thicker texture with greater mass

(e.g., mm. 535-550).

A

wave group is a series of waves of similar proportions. This term can

also be used in the general sense of a series of waves that group to form a

section within the mosaic structure, e.g.

ABAB, or (ABC ABC), etc. The mosaic structure, with its reliance on

well-defined and organized modules, plays a central part in this grouping of

waves into sections. A wave train is a series of waves coming from the

same direction. Waves in a wave train are part of the same process, line, or

“train” of thought. In Jeux, this is most noticeable at the

motivic-thematic level, where motivic particles are ‘propagated’ and

‘regenerated’ from wave to wave, forming a continuous motivic thread, and thus

coming from the “same direction.” The continuity of wave trains is often

enhanced through a gradual intensification of waves within the wave train which

helps group the waves into a larger wave or section. Waves can also combine to

form a choppy sea, a state of the sea characterized by short, rough

waves tumbling with an abrupt and quick motion. A cross sea is a more

confused and irregular state the of the sea due to groups of waves coming from

different directions, the musical analogy of which would involve combining wave

trains and phasing, possibly with other features such as refraction and

breaking. A series of waves may also be

related by systematic processes of phasing, damping, amplitude

modulation or frequency modulation, or constructive and destructive wave

interference, though this is not common in Jeux.

Textural

or statistical waves can appear in simple or more “ornamented” or “embellished”

forms. Whereas a basic wave may consist of a simple rise and fall, an

embellished wave might rise in several stages, or “smaller partial waves” where

“the successive climaxes add up, as it were, to one big wave.”

A wave may crest, climax, or break in different ways, and may recede in several

stages A wind-up can also function as a form of embellishment. Zuckerkandl says

“the wave will display contours now soft and rounded, now sharp and jagged; and

will beat softly and calmly or with ever-increasing impact; will heave, topple,

break against resistances.”

One form of the wave “embellishment” analogy which Debussy favors and uses

numerous times in Jeux is the uprush (or swash), the rush of

water up the foreshore following the break of a wave, usually of less intensity

than the other parts of a wave, and which should be distinguished from the

surge of a breaking wave. Debussy also uses the opposite effects of a backrush

(or backwash), of water receding back into the sea, and of undertow, an

underwater current caused by backwash, which produces an attenuation and

retards the flow or reverses the process. Other naturally inspired forms of the

ornamental play of waves include reflection, in the form of echo-like

repetition or variation of a wave or fragments thereof, usually from the tail

end, and refraction, the transfer of wave motion between two different

mediums or between immiscible states of the same medium. Debussy creates the

effect of refraction by transferring wave energy between contiguous and

differing textural and/or motivic-thematic organizations. This transfer of wave

energy often occurs between the intensification to the de-intensification phase

of a wave, or, in more elaborate form, between the stages of the

intensification phase of a wave. The modular aspect of the music is highlighted

with this technique. However, the underlying continuity, the “hidden impetus,”

or invisible “current” of the wave process is always present.

A

sense of flow is always present in the “ornamental” play of waves in the form

of varied ebbs, lulls, surges (upwellings), eddies,

swirls, and the mostly laminar though sometimes turbulent

flow of particles. Debussy’s typical harp glissandi produce the effect

of a smooth and laminar flow of particles. A more delicate wave pattern occurs

in the form of ripples (or capillary waves), which have a musical

analogue in the form of trills, vibrato, and tremolo (e.g., mm. 690-693). In

addition, there are the soft, “luminous,” and shimmering textures of Jeux,

with their dynamic nuances and attention to detail, which are analogous to the

‘sparkle’ on the surface of the ocean as it reflects the sunlight, along with

the spray, mist, water droplets, and foam, and which is projected through the

coloristic orchestration, trills, tremolos, glissandi, “musical pointillism,”

“sound textures,” and general ornamentation.

In

summary, there are waves of many shapes, heights, lengths, speeds, rates, slope

angles, etc. The play of waves in Jeux expresses the gamut from soft to

loud, slow to fast, simple to elaborate, and delicate and playful to powerful,

and can be “stormy and varied.” There are waves of many types, including

breakers and non‑breakers, different length climax moments, from

attenuated to short, to fuller and longer releases, or energetic breaks,

progressive waves, standing waves, slow motion waves, reflected waves,

refraction versus no refraction, wave phases in stages, uprush, undertow, deep

water waves, wave groups, wave trains, and large‑scale wave processes.

There are rhythmic‑motivic waves (e.g., mm. 627‑648) and lyrical‑thematic

waves (e.g., mm. 264‑283). The “game of waves” in Jeux includes

“waves of every color and mood.”

These composed‑out waves can be extremely varied and flexible in their

behavior, even capricious and dramatic. Moreover, the statistical waves are

part of the general cyclic processes of Jeux related to the global

form, or ‘vegetative’ organic regeneration,

of the motivic‑thematic process. The wave process thus operates at

different levels, from local to global (e.g., propagation is contiguous, regeneration

is non-contiguous), including the micro-level of motivic particles, the

layering of metric waves of the mosaic structure at the middle level, and the

statistical waves, wave groups, and larger scale wave processes of the

macro-level. Again, parallel cyclic elements are found in Middle‑Eastern,

Indian, and Balinese music and cosmologies, in some examples of Western music,

and are ultimately universal in nature. The idea of musical waves, or wave‑like

shapes in music, both melodic and statistical, is not necessarily new, though

not as unique and developed as those of Jeux. Debussy applies wave and

cyclic ideas at many levels, which together with their non‑functional

qualities, incorporation of discontinuous elements, modern harmonic materials,

“textural” orchestration, etc., sets them apart as unique and innovative.

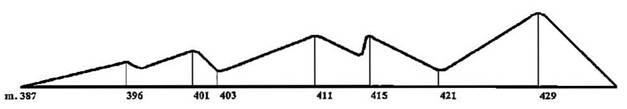

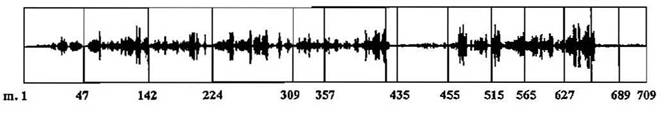

Analyses

of Waves in Jeux

The

dialectic of continuity and discontinuity in Jeux is expressed not only

through the duality of mosaic structure and waves, but also through the relative

continuity and discontinuity of the wave process itself. This occurs both

within individual waves and series of waves, and is in addition to the process

reversal of intensification followed by de-intensification which is

characteristic of all wave motion. At the level of individual waves, the

intensification phase builds energy which seeks release during the

de-intensification phase. The inhibition of this process creates a play between

two kinds of waves: waves that release, either gradually, or

suddenly, as with a breakers, and waves that do not release, which are

inhibited, suppressed, attenuated, deflected, anti-climactic, or cut-off. This

process is likely inspired by the play between ocean waves that break and do

not break.

At

the next level of a series of waves, or between waves, there is a play between

two kinds of wave processes: waves that continue, through release,

momentum, periodicity, wave trains, development, and waves that do not

continue, through interruption, inhibition, attenuation, or damping. The

terms release and continue are similar and are used in a relative