An Introduction to Jo Kondo’s Sen no Ongaku Music of 1973 to 1980

John

Cole

The

composer Jo Kondo has a very special position in contemporary music, not just in

his home country but internationally. Along with teaching in Japan (at present,

he holds a professorship at Ochanomizu University in Tokyo, and continues to

teach a composition class at Tokyo University of Fine Arts and Music). He has

taught in England, Canada and the United States and he is a prolific writer,

author of five books and over one hundred publications on topics covering all

musical matters ranging from his own music and music aesthetics, to interviews

with important contemporary composers. While Kondo's music has been discussed

in various publications, an examination of his entire body of work has not yet

been attempted.

An

examination of Kondo’s entire oeuvre shows a surprising consistency of style in

works from 1973 to the present. Kondo

refers to this style as "sen no ongaku" which he translates

into English as "linear music". One of the main objectives of this

study is to show how Kondo is able to adapt the essential elements of sen no

ongaku to compositions of various instrumental combinations and scale, from

solo and chamber works, to compositions for much larger ensembles and

orchestral pieces. The year 1973 is significant as it was the year Kondo

started overtly composing with sen no ongaku, and the year 1980

represents a change in style in which vertical relations became emphasized over

horizontal relations. Thus, examining in detail the pieces from 1973 to 1980 it

will be possible to contextualize the origin and particular points of

development of sen no ongaku in Kondo’s music.

Another

of the decisions made at the onset of this study was to limit the discussion to

a concrete examination of his scores and recordings. While some aesthetic and philosophical

problems are touched on, this enquiry is concerned in no way with any extra‑musical

or philosophical concerns outside the music itself. Thus wherever possible, an

attempt will be made to rely on aural confirmation in recordings and to avoid

both claims based on score analysis without connection to the concrete sound,

and the search for obscure and impalpable theoretical connections.

The

Earliest Definition of 'Sen no ongaku '

Chronologically,

the first mention of the term 'sen no ongaku' in the composer's writings

is found in the liner notes of the album of the same name released in

1974. These were written to briefly

introduce his new theory and to explain the compositional methodology of Orient

Orientation (1973), Standing (1973), Falling (1973), Click

Crack (1973), and Pass (1974)

recorded on this album.

Kondo

begins the explanation of the his new theory as follows:

"Sen

no ongaku" can be roughly translated as "linear music". At first this music will sound to most people

like a row of endless tones that proceed without interruption, always wrapped

out in a kind of simple artlessness.

Let

us begin examining Kondo's description of sen no ongaku as "a row

of endless tones," a phrase which aptly applies to the first sen no

ongaku work Orient Orientation written for any two melody instruments

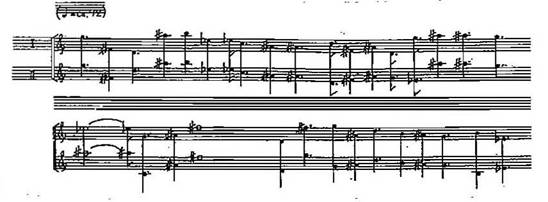

of the same kind (Example 1).

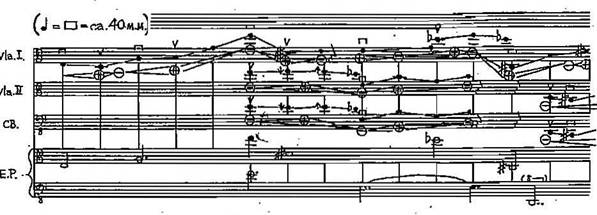

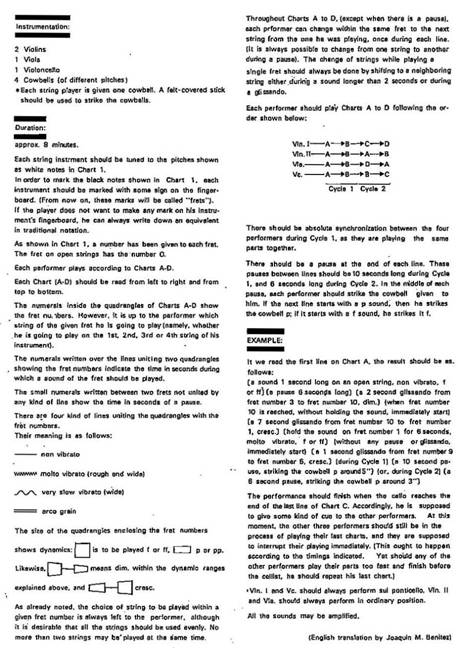

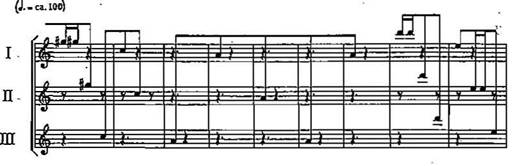

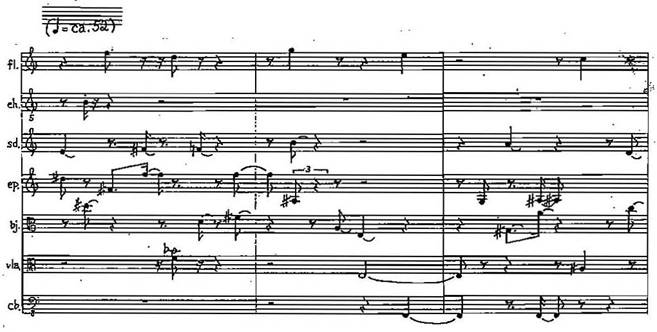

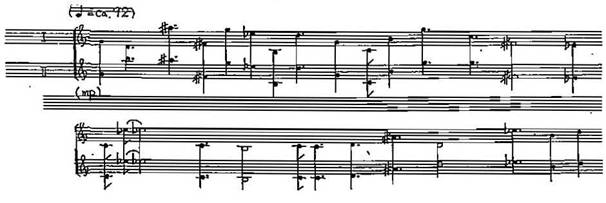

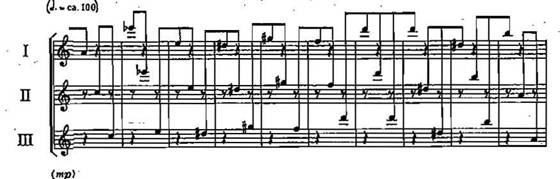

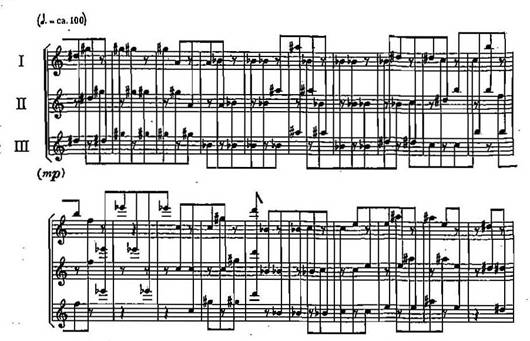

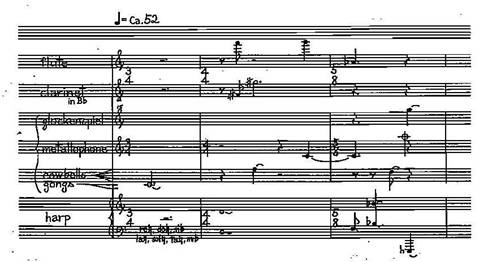

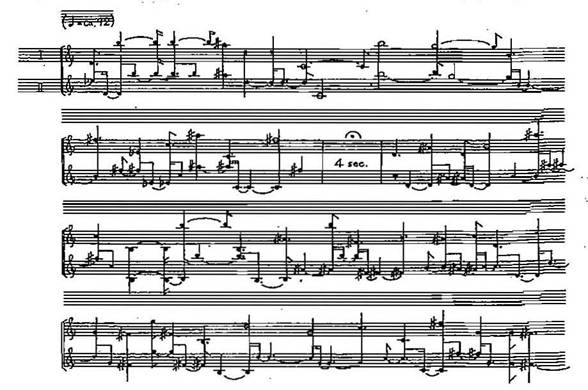

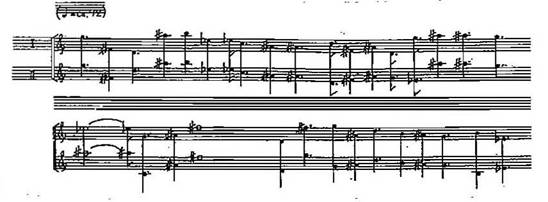

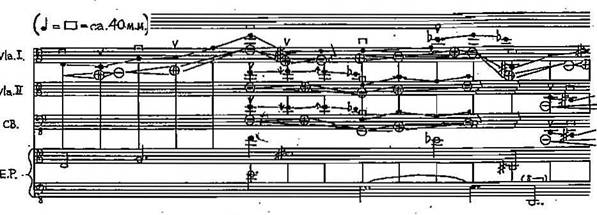

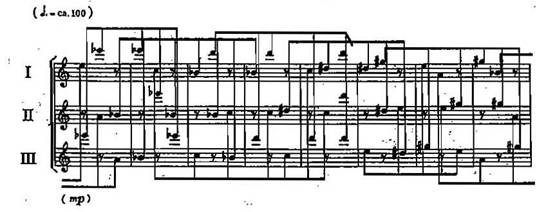

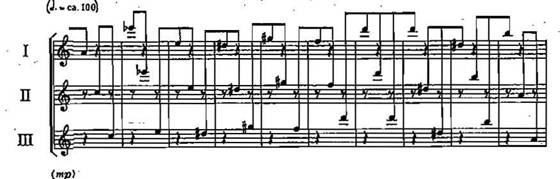

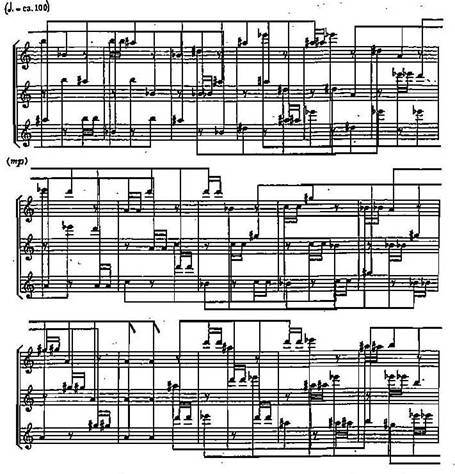

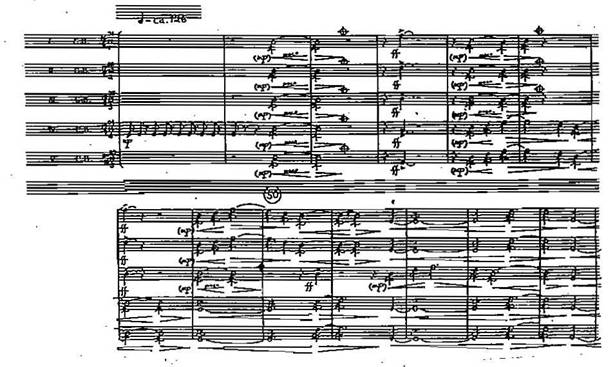

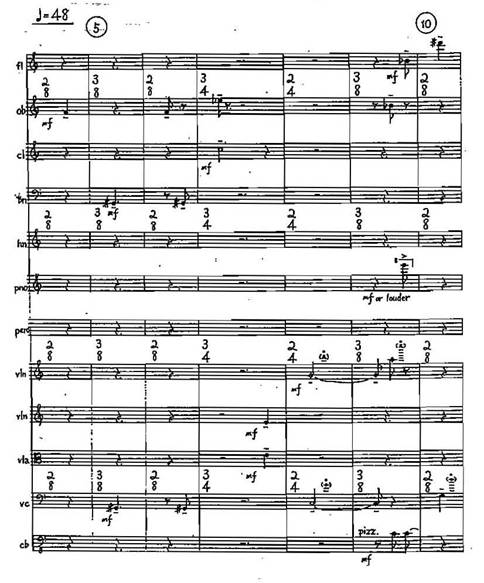

Example 1: Orient

Orientation: page 1, first system

If

we glance at an excerpt from a stylistically quite different work from the same

year as Orient Orientation we can see the manner of working with a

"row of endless tones" expressed in a slightly different way (Example

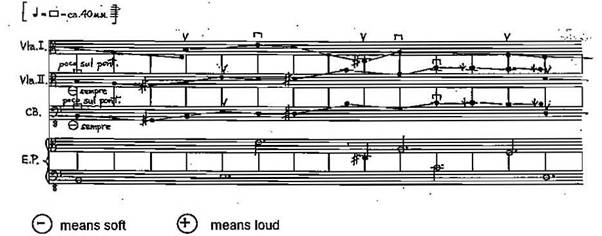

2).

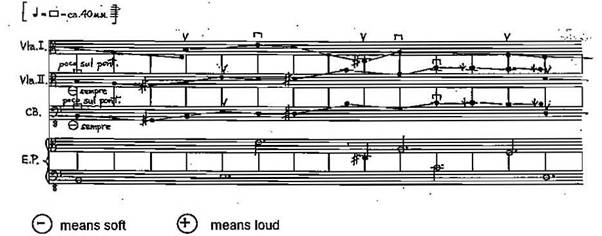

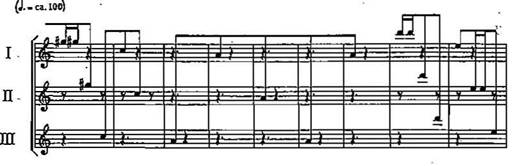

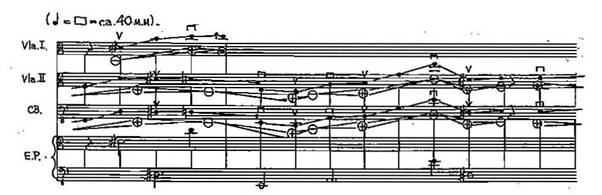

Example 2: Falling: page

2, first system Dynamics

of the sounds of electric piano are always free between ppp and mp.

Here,

in Falling for 2 violas, double bass and electric piano, we have a

four-part texture of four rows of tones. The row of tones of the electric piano

part, which is very similar in character to the Orient Orientation rows,

is combined with the three rows of tones written for the two violas and

contrabass. In this example the slanting

lines in the string instruments represent glissandi. Due to the consistent use

of glissandi throughout the composition, these string instrument parts, while

incorporating visibly linear note rows, have a very different sound quality

from the rows of the electric piano part. In this context, due to the absence

of a clearly articulated series of individual attacks, the rows written for the

three string instruments have the quality of continuous undulating waves of

sound. In Falling, Kondo is experimenting with "a time lag shift in

the mobility of a sound that keeps neither fixed pitch nor dynamics."

The

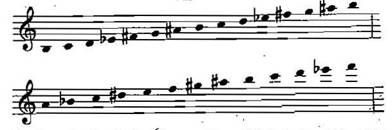

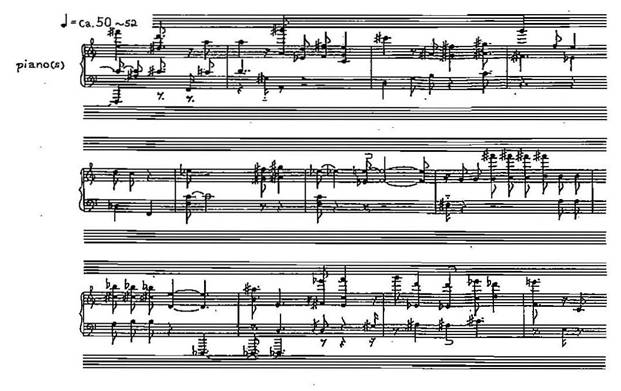

following two lines from Click Crack for solo piano present another slightly

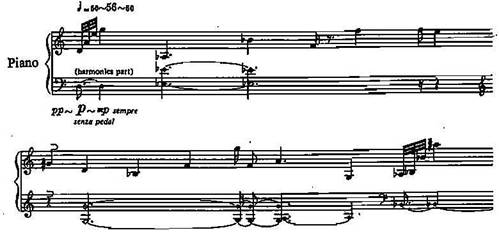

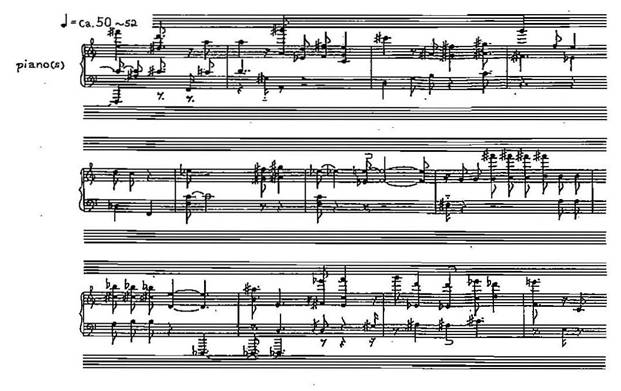

different treatment of a row of tones (Example 3).

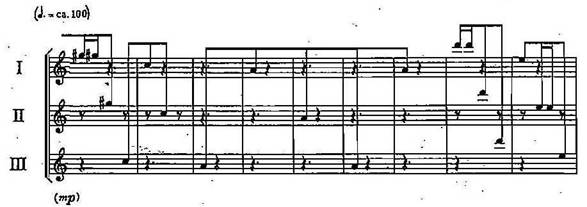

Example 3: Click

Crack: page 1, first 2 systems

In

this example the row of tones in the upper staff is combined with an extremely subtle

chordal accompaniment of barely audible piano string harmonics in the lower

staff. By silently depressing the keys of the piano (the diamond shaped

pitches) while playing the upper line, these harmonics are made audible through

the sympathetic resonance of the undampened strings. Due to the incorporation

of rapid groupings of thirty‑second notes, the note row in the upper

staff is more florid and gestural than the note rows of the two previous

examples.

In

Standing, written for three instruments of different families, we

recognize a degree of complexity not encountered in the previous examples

(Example 4). Complexity in this example arises from three conditions. First,

the rows of tones in this composition are distributed among three, rather than

one or two voices. Second, most of the composition is made up of two

independent lines moving in tandem, creating harmony in the form of two‑note

chords, which has the effect of blurring the boundaries between the two lines. Third,

the direct note repetitions distributed among the three lines continuously vary

in number, creating very irregular rhythmic patterns.

Example 4: Standing:

page 15, first system

After

explaining the outward appearance of the new sen no ongaku style as a

"row of endless tones," Kondo moves on to discuss the specific

functions of sound groupings which "enable the listener simply to gaze at

each sound dispassionately¼." It is important to note this first mention of

Kondo's concern with the relationship between sound groupings and listening as

it forms such an important role in subsequent writings.

The

next important point in Kondo's introduction to sen no ongaku style is

his concern with the "spatialization" and "positionings" of

tones in a sound‑space. He writes:

Each

single tone we deal with is not a self‑sufficient, indivisible particle,

but one that has been spatialized ¼ each

spatialized single tone ¼ endlessly

uncovers manifold positionings in that sound‑space.

Kondo's

idea of "manifold positionings" can best be explained with reference

to the formation of melody. A “melodic grouping” is a collection of tones

grouped in a relatively tight unit in which each individual tone contributes in

some way to the perception of the whole as a single entity. If single tones are

grouped too far apart, the tones are not perceived as being connected to each

other, and consequently, the sense of these tones forming a melody is weakened,

or even non‑existent, depending on the distance between individual tones.

In the case of conventional melody the individual notes must sacrifice some of

their individual identity in order to form a grouping which can be registered

by the listener as a single entity. In this sense, a note within a melody has a

relatively restricted "positioning" in relation to the notes

surrounding it. To cite a rather obvious example, if the notes of any well‑known

melody are slightly re‑arranged, the tune is rendered incomprehensible. Or

if a melody's tempo is altered considerably it might not be perceived as

melody, but rather as “figuration”, or even “texture”.

Kondo's

note rows of sen no ongaku works are very close in character to

conventional melodies in terms of their continuity and general contour. But

they lack the specific fixed "positionings" of individual notes

grouped in such a way that a clear melody is perceived. The main aspect of

melodic tone grouping that Kondo is interested in preserving is the manner “of

note‑binding”, or a note's potential for connection with other notes. If

the note rows stray too far from conventional melody, with too few or no

connections between tones, the groupings tend to resemble chance music where a

sound's particular positioning in relation to other sounds is redundant.

Because

the “binding relations” of sen no ongaku tone rows are not as rigidly

fixed as conventional melody, the individual notes have more autonomy, and are

capable of being positioned in a great variety of potential groupings or

"manifold positionings." Because of the relative looseness of the

groupings, a row of a sen no ongaku work may be interpreted in a myriad

of ways depending on the particular predilection of each individual

listener.

Finally,

and most importantly, one of the most definitive aspects of sen no ongaku

is the musical continuity which Kondo explains in the following manner: "'Linear

Music,’ considered as a row of tones articulated in single note units, acquires

a continuity based on an endless pulse." These words of Kondo written in 1974,

succinctly define an important aspect of sen no ongaku which we will

examine repeatedly and in detail throughout

the analyses of this study.

Terminology:

“Sound Shadow” and “Sound Grouping”

Two

important terms appearing for the first time in the liner notes of 1974, which

Kondo used to explain his new theory of sen no ongaku were “sound

shadow” and “sound groupings.” Defining Kondo's “sound shadow” in a concise

manner is difficult as the only written description of the term by the composer

in the liner notes to his first LP album, is somewhat abstruse.

The five works on this album however, suggest certain concrete implications of the

term. While ‘sound shadows’ can take many forms, one of the more common of

these is that of a tone or continuous sound directly following a leading voice,

most often in the form of a staggered repetition of a single note. The ‘sound shadow’ technique first appears in

the very first work written in sen no ongaku style, Orient

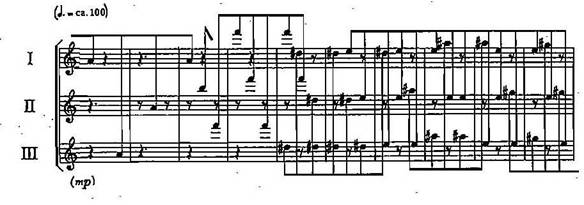

Orientation (Example 5).

Example 5: Orient

Orientation: page 2, system 7

(The

instrumentation of this work is for any two melody instruments of the same kind)

In

some works the sound shadow can be likened to a hocket‑like effect as

below (Example 6).

Example 6: Standing:

page 1, system 1

In

other works the “sound shadow” manifests itself as an asymmetrical sound

aggregate or “echo”. In Falling (Example 7) the leading first viola line

follows the attacks of the electric piano "with a moving shadow that tries

to coincide with them."

This first viola line is then “shadowed” by the second viola and double bass

playing in two‑octave unison.

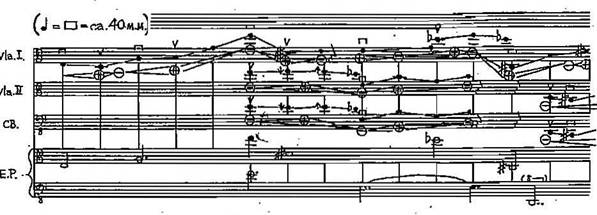

Example 7: Falling:

page 2, system 4

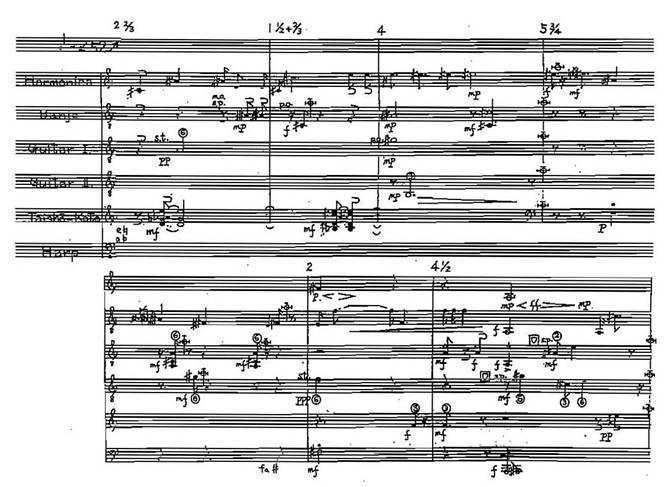

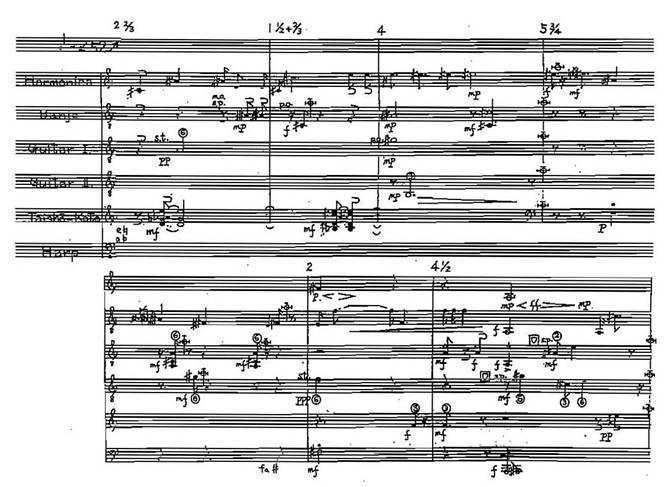

The

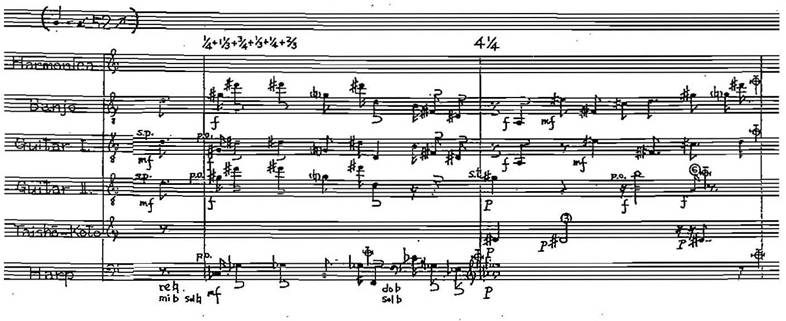

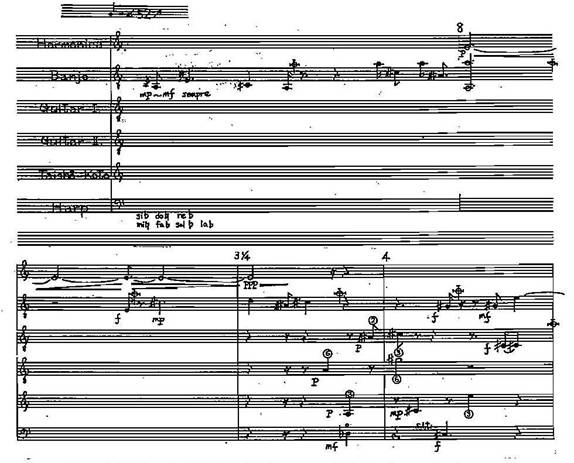

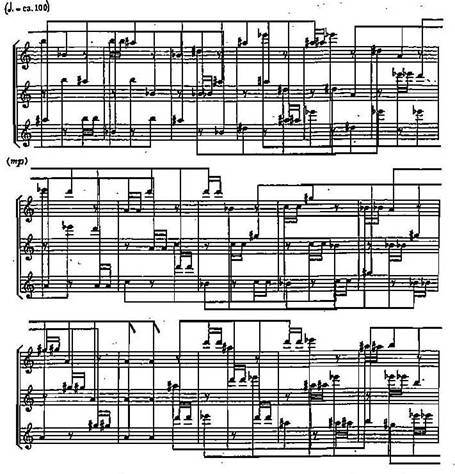

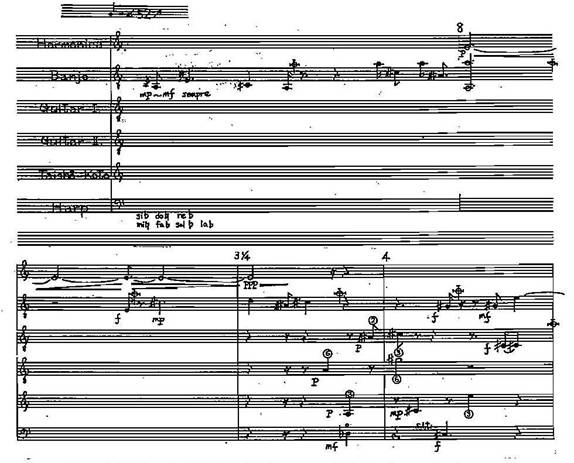

more thickly textured work Pass, written for a slightly larger ensemble of

banjo, two guitars, taisho‑koto, harp and harmonica, displays the freest

use of the “sound shadow” technique so far (Example 8).

In

this work the “sound shadow” is not readily discernable. Kondo explains this

veiled “shadow articulation” in the following way: "Here the shadow is

allowed free motion, it is even provided with an independent structure that

could almost be called a figure for each instrument."

The banjo in this work has the central role of "carrying"

the sound shadows of the other instruments. Because the instrumental lines are

so rhythmically varied, the resulting articulation of their shadows is quite

irregular. This technique of “shadow articulation” is very different in

character from that seen in Examples 5 and 6.

Example 8: Pass:

page 9, system 2

The

function of the “sound shadow” is to draw attention to the note sounding

immediately before, in order to reinforce the independence of this note as an entity

in and of itself. The reciprocal relationship between sounds and “sound

shadows” employed here has the dual function of not only drawing the listener's

attention toward the individual tones, but also of discouraging the tendency of

the listener to hear the pitches as part of larger conventional melodic

groupings.

As

we can see from the above explanations, it is clear that for Kondo,”‘sound

shadows” have two functions. The first is the framing of individual tones in

order to highlight their independence from each other, and the second consists

of the "positioning of tones within a compatible succeeding

relationship" through the delicate rhythmic placement of the shadow tone.

Kondo's conception of a “row of tones”

here is far from structural. For him a row of tones is less a collection of

material for building and constructing, than a random selection of pitches used

for experimenting with “shadow articulation”. The consistent use of “shadow

articulation” throughout a work is one method used by Kondo to avoid the

formation of conventional note groupings.

The

term “sound groupings" refers to the way pitches are arranged in a

composition. Stated simply, they can be grouped in one of two ways: vertically

(harmonically) or horizontally (melodically). While both methods of grouping

are used in Kondo's linear music, in most of the works from the first period

horizontal groupings of sounds are more prominent than vertical groupings.

Before

moving on to a detailed description of the note rows an important point in the

definition of a sen no ongaku row must be clarified, namely that Kondo's

definition of a sen no ongaku row should not be confused in any way with

a 12‑tone row or a serial row. Kondo later uses the term “pitch gamut” to

dispel any connection with the latter two terms.

One of the most important distinguishing features of linear music pitch gamuts

is their 'non structural' nature.

Kondo's

theory of sen no ongaku centered on a new method of grouping sounds.

This new method of organization or "spatialization" of pitches

avoided strong tonal centers, melodic climaxes and functional harmony. “Pitch

gamuts” in linear music can be considered to have a loose correspondence to a

“tone row” or melody, but due to the lack of tight groupings of notes, the

often rhythmically irregular positioning of sounds in time, and the careful

attention given to the self‑sufficiency of each sound in the line, we

must consider Kondo's horizontal groupings of tones a radical departure from

the idea of melody in the conventional sense.

Kondo's

horizontal groupings differ further from traditional melody in their

aimlessness or non‑directionality. Because Kondo's “rows of tones” are

organized in a non‑hierarchical manner with a clear absence of

goal-directed movement, the individual notes of these rows float in time in an

often rhythmically and harmonically ambiguous state. The most important

objective of this new pitch organization is the maintenance of the self‑sufficiency

of each tone when it is sounded. Whil we can consider Kondo's pitch gamuts as a

kind of structural foundation of each work, they are not treated in a

conventionally structuralist manner.

That is to say that the individual pitches of these gamuts are not

combined in sound groupings to form a greater whole, but are rather grouped in

a manner that encourages their mutual independence, a kind of semi‑autonomous

state.

Kondo's

intention here is to encourage a different kind of listening ‑ an

attention to individual sounds over conventional melodic and harmonic groupings

of sounds. This is not to say that Kondo is unconcerned with the relationships

between the individual sounds but rather that he wishes to avoid "the

problem posed by sound grouping¼centered

on the structure of sound aggregates [resulting] from the accumulation of

tones"

which suggest conventional expressive melodic formations.

In

order to encourage this kind of listening, the particular manner in which sounds

are grouped is of the utmost importance. If certain sounds in a pitch gamut are

placed closer together than others, the ear naturally groups them as a

distinctively identifiable unit setting them apart from other less dense

groupings. If, on the other hand, all pitches are placed relatively equidistant

from each other, the individual tones lose their self‑sufficiency and are

subsumed into a rhythmically static whole. Kondo is interested in creating an

ambiguous state in which note groupings of greater or lesser density cannot be

readily distinguished from each other. The composition of these early linear

music works represents Kondo's first grappling with a delicate balancing act ‑

a searching for a means of grouping sounds to achieve what he later termed

"the proper degree of ambiguity and vagueness."

He explains his theory of the function of note groupings in the following

manner:

¼if the

groupings are too vague, the sounds lose their mutual relationships, and the

outcome resembles Cage's chance music. If on the other hand, the groupings are

too unambiguous, the listener ends up listening only to the resulting structure

and falling prey to its expressive effects. It is essential to find the proper

balance, an arrangement where sounds are heard as mutually connected by

groupings, and yet each sound keeps its own individuality without becoming

completely submerged under the upper level structures.

Kondo

explains this balance in more concrete terms when speaking about Sight

Rhythmics (1975) in the same article:

In short there is a melody‑like

structure, but it is never unambiguously established; it is almost a melody,

yet not quite. The listener can feel that a melody‑like structure exists

(which is precisely the syntactic device I use to bind the individual sounds

together), but he is still able to recognize each individual sound in its own

right. He perceives the individual

sounds through a 'melodic prism' as it were.

As

we can see from these two quotations, Kondo's theories regarding sound

groupings extend beyond a purely structural concern with how pitches can be

ordered or combined in a composition to form a coherent whole as in Schoenberg.

It is through the employment of a melody‑like structure that Kondo is

able to focus on what interests him most ‑ encouraging of an active kind

of listening, from instant to instant, in which the listener groups the

individual sounds of the work into various configurations based on their own

preferences.

Almost

all of the works composed in this period conform to the characteristics of the

new, sen no ongaku style in terms of their extremely sparse texture,

static quality and the use of a single melodic line as their basic material. From

1973 Kondo had found his voice, and in this year alone wrote no less than six

works to outline his new theories. The abrupt shift in style in 1973 was a

conscious one as we can see from his desire to explain his new theory in detail

in the first two chapters of his book Sen no ongaku. This stylistic

shift is even more striking in retrospect when we consider how important the

ideas outlined in Sen no ongaku were in the formation of a distinctive

style, which can be recognized throughout the composer's entire body of work

from the first “linear music” pieces to the present.

There

are a few works in this period, however, which do not so easily conform to the

characteristics of the new, sen no ongaku style. We will begin this section with a brief

discussion of these works. These exceptions are Mr. Bloomfield, His Spacing

(1973) for string quartet, MINE (1974) for chorus, Ashore (1974)

a work of indeterminate duration for tape, flute, piano, electric organ, harp

contrabass, percussion and harmonica, Kekai‑Sekai (1976) for mixed

chorus and Riverrun (1977) for tape. We will focus on only one of these

works, Mr. Bloomfield, His Spacing, which retains aspects of both pre‑sen

no ongaku and sen no ongaku style.

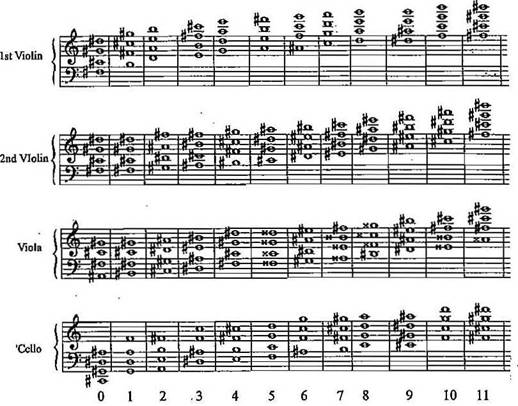

Mr.

Bloomfield, His Spacing

Mr. Bloomfield, His Spacing, for string quartet and

cowbells, is somewhat hard to categorize stylistically.

Although it was written after Orient Orientation, and does display some

characteristics of sen no ongaku, in terms of its overall sound world

and quality of musical gestures, this composition has affinities with the

pieces written before 1973. In particular it has a certain likeness to the

earlier work Breeze (1970) through its use of graphic notation,

labyrinthine instructions for the four performers, its focus on attentive

listening, and its experimental atmosphere. It has connections to the new sen

no ongaku style in terms of its formal clarity, stark reduction of musical

material, and fixation and limitation of musical elements. Perhaps most

importantly, this is the first composition to use rhythmic unison which is the

most important structural aspect forming the backbone of almost all works

written in sen no ongaku style.

Mr. Bloomfield, His Spacing was the last piece

in Kondo's oeuvre to include extensive detailed instructions for the

performer. It is one of only four works

by the composer written in graphic notation.

From this point on, with only one exception (Jo‑ka), all of

Kondo's work is conventionally notated.

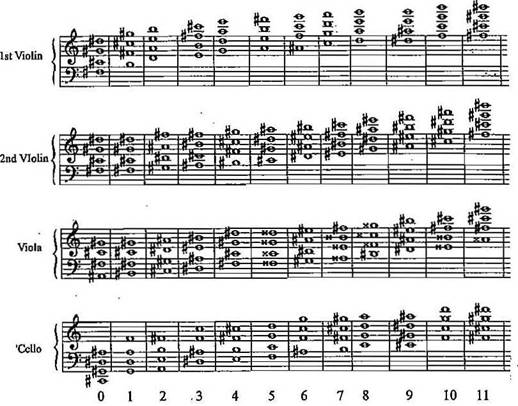

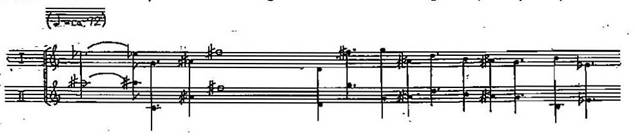

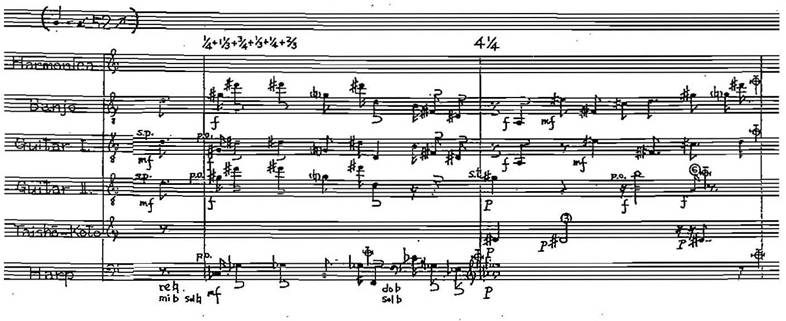

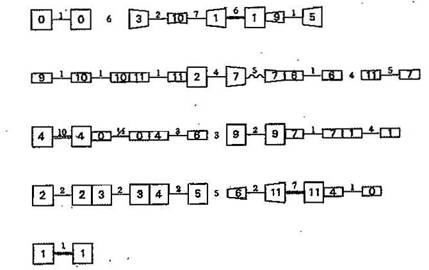

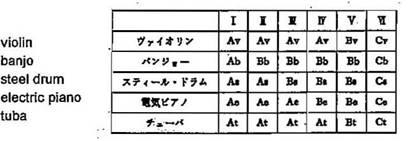

The score includes five charts with an accompanying page of

instructions. One of the five charts (referred to as Chart 1 in Kondo's

instructions), is a scordatura and fingering position chart for the four

string instruments (Example 9).

The

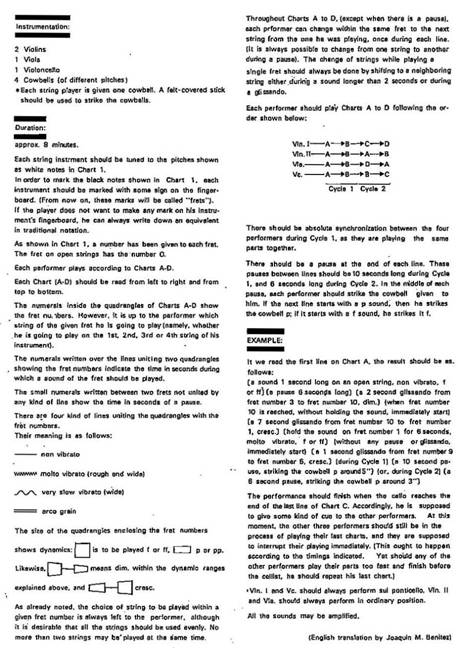

remaining four charts (lettered A, B, C and D in the score), are written in

graphic notation. Because all four charts are so similar in appearance, we need

only refer to one example. Chart A is shown below (Example 10). Because the

instruction sheet explaining this chart is so comprehensive, it is included

here in its entirety. A quick glance through this page of instructions is the

simplest way of grasping the technical details of the work.

Kondo

favors a strict reduction of material and fixation and limitation of musical

events to create his musical image. Kondo's directions are very concise with

the single parameter of pitch being the only indeterminate element of the

composition. Compared to the work Breeze, which also employs

indeterminate elements, Mr. Bloomfield, His Spacing is a much more

tightly controlled work. This control is manifest in the notation, through the

very clear treatment of the four parameters of pitch, duration, dynamics and

timbre.

The

most notable aspect of Mr. Bloomfield, His Spacing is that Kondo is able

to articulate such a clear musical image through graphic notation. An important aspect of this notation is the

careful balancing of indeterminate and determinate elements. If indeterminate

elements are too predominant, formal clarity is lost. On the other hand, if every musical parameter

of the work is too tightly controlled, the piece loses flexibility and

spontaneity, which are both essential qualities contributing to the playful

atmosphere and character of the composition.

An

unusual feature, which contributes greatly to the character and identity of

this work is the inclusion of four cowbells, each of different pitch to be played

by the four string players. Kondo uses the cowbells in a structural, rather

than coloristic manner, to punctuate pauses at the ends of musical lines, and

to amplify breaks in continuity. The inclusion of these unusual non‑pitched

instruments into an otherwise conventional ensemble is a device used by Kondo

to offset the listener's expectation, by adding an unstable element into an

otherwise conventional sound world. We will see this technique in many future

compositions.

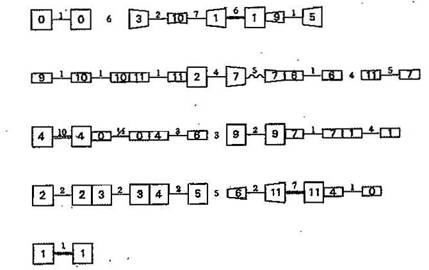

The clarity of the piece can be seen in the

way Kondo organizes large sections of material in a strict formal scheme. In

the top right hand side of the sheet of instructions (Example 11) we see a

figure designating the particular order in which charts A to D are to be played

by each performer. The work is divided into two major sections which Kondo

terms "cyles." The partitioning of the work into two contrasting

cycles is an important formal stratagem which helps to structure the work in

two important ways. First, the re-inclusion of the A and B charts from Cycle 1

in Cycle 2 aids in the comprehension of a quite abstract sound world through

repetition. Second, a kind of musical development is suggested through the

introduction of new material (charts C and D only) in the second cycle.

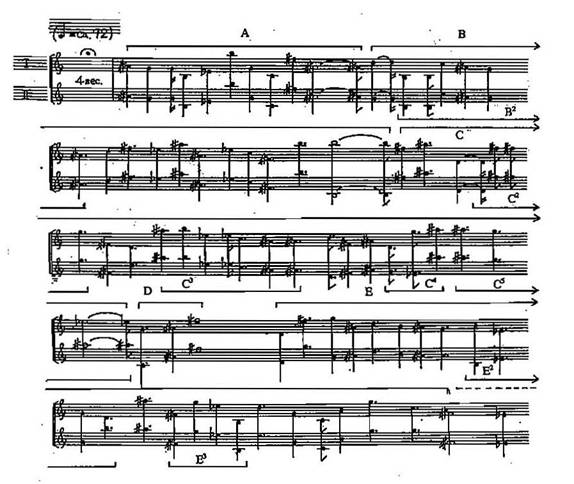

Example 9: Mr.

Bloomfield, His Spacing: Scordatura and Fingering Position Chart (Chart 1)

Example

10:

Mr. Bloomfield, His Spacing: Chart A

Example

11:

Mr. Bloomfield, His Spacing: Instructions

‘

The

use of rhythmic unison in Cycle 1 should be noted, as it is the first

appearance of a technique Kondo will employ in most of the sen no ongaku

works to follow. Rhythmic unison is used here to structure sounds not organized

in conventional harmonic or melodic groupings. From the listener’s point of

view, this aspect of the perception of things sounding together and things

sounding apart becomes very important in a work employing few recognizable

syntactic devices.

While

the jagged gestures, discontinuity and somewhat harsh sound world of Mr.

Bloomfield, His Spacing seem far removed from the lightly‑textured sen

no ongaku music it bears affinities with the new style in its definition

and limitation of musical elements, its simplification of material distinctive

formal clarity and most importantly, the first use of the rhythmic unison

technique which forms the backbone of virtually all works written in sen no

ongaku style.

Sen no ongaku Works: 1973 to 1980

To further aid the

discussion of sen no ongaku, the following six essential features of

this style are summarized as follows:

1. groupings of tones in order to

encourage multiple interpretations

2. vertical formations in no way

connected with functional harmony

3. non-teleological continuity

4.

single texture throughout a composition

5.

consistent use of asymmetrical rhythm throughout a composition

6. uni-sectional static form

It is important to

remember, that in spite of the development of sen no ongaku these six

features remain constant during the period 1973 – 1980. The flexibility of the sen no ongaku

style is revealed here in terms of how it is able to incorporate a wide range

of diversity while still adhering to these six principle features. We will

begin this examination of Kondo’s sen no ongaku style with a discussion

of melodic aspects. This is followed by an explanation of rhythm and meter and

vertical formations. Next, structure and form are treated, before concluding

with a discussion of mature works of the period.

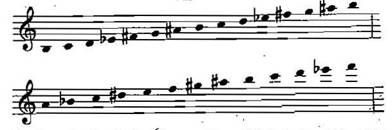

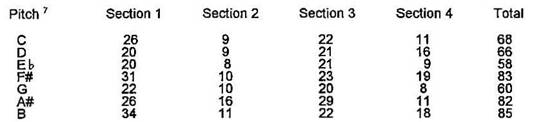

In the

case of the works, Orient Orientation, Standing, and some other

compositions written up to 1975, the limitation of pitch content “was decided on

the basis of a chart of random numbers assigned to a gamut of sounds purposely

chosen beforehand.”

These gamuts of sounds, unique to each composition, are arranged in various

vertical and horizontal configurations, in an intuitive manner. The two gamuts

shown below very closely resemble serial pitch-sets, but they are in no way

treated as such, being merely the pitch material of the composition which is

organized using a combination of random and intuitive procedures (Example 12)

Example

12: Gamuts Used in the Composition of Orient

Orientation and Standing

In the

following example, the notes of the gamut “E” from Example 12 are arranged in a

line. This is the simplest form of arrangement of the notes of a gamut (Example

13).

Example

13:

Orient Orientation: page 3, eighth system

The notes

of a gamut may also be combined in vertical aggregates as seen in Standing

(Example 14).

Example

14:

Vertical Configurations of Notes of the Gamut, Standing: page 13, third

system

Example

15:

Click Crack: page 4, systems 5 and 6

Melodic

Style Categories

The five sen

no ongaku compositions on Kondo’s first record album are stylistically

quite contrasting works. While all are based on a single melodic line,

the specific treatment of this line varies quite radically from composition to

composition. The reader need only

compare a few bars of the two works Standing (1973) (Example 16) and Falling

(1973) (Example 17) to recognize the range of this contrast. Here we have two

completely contrasting treatments of a line of tones, yet both conform to many

of the six features outlined at the beginning of this section. Comparing the various treatments of the

melodic note groupings in other works of the this period, equally striking

variations in style can be seen. To aid

comparison these variations are organized into three different stylistic

categories: simple melodic style, leaping melodic style and pointillist melodic

style.

Example

16:

Standing: page 7, fourth system

Example

17:

Falling: page 7, first system

Simple Melodic

Style

The

clearly audible arrangement of tones seen in the first sen no ongaku

work Orient Orientation (1973) is representative of the

simple melodic style (Example 18).

Example

18:

Simple Melodic Style, Orient Orientation: page 4, fifth system

Another

example of simple melodic style is seen in Click Crack (1973) (Example

19).

Example

19:

Simple Melodic Style, Click Crack: page 9, first system

Leaping

Melodic Style

Leaping melodic

style lacks the smooth connection between pitches found in simple melodic style

due to the frequent occurrence of large melodic leaps (often greater than an

octave) and clearly audible breaks in continuity through the occasional use of

rests. A clear example of leaping melodic style can be seen in the banjo part

of the work Pass (1974) (Example 20).

Example

20:

Leaping Melodic Style, Pass: page 1, first and second systems

The

extreme melodic leaps throughout Retard (1978) for solo violin fracture

the continuity of the line to such a degree that the composition appears to be

written in three independent voices. Employing a technique very similar to that

found in Bach’s unaccompanied violin sonatas, Kondo fixes certain tones of the

gamut in one of three distinctive registers of the instrument (low range on G

string, middle range on the D and A strings and high range played in harmonics,

see Example 21).

Example

21:

Leaping Melodic Style, Retard: page 4, seventh system

As mentioned

above in footnote 28, the line of tones of some sen no ongaku works may

fall under more than one category, as in the case of certain sections of Click

Crack. While this work for the most part is written in simple melodic

style, the leaping melodic style can also be seen (Example 22).

Example

22: Leaping

Melodic Style, Click Crack: page 8, first and second systems

This

excerpt is close to simple melodic style in terms of the connectedness of most of

the tones and the general contour of much of the quasi-melodic line. However,

the three rests in the first half of the first system and the leap from the

high A# to the low G, along with the repetitive leaping figure at the end of

the first system, fall more into the category of leaping style. A return to

simple melodic style occurs in the second half of the second system from the G

onward.

Pointillist

Melodic Style

A more

sophisticated melodic style involves the shifting of melody between various instruments

in a pointillist manner. Sight Rhythmics (1975), (both versions), Strands

I (1978), When Wind Blew (1979), An Elder’s Hocket (1979) and

An Insular Style (1980) are the six pieces of the period 1973 – 1980

which use this technique. The pointillist melodic effect in the ensemble

version of Sight Rhythmics is more prominent than the piano version due

to the shifting of the melody between instruments of sharply contrasting color

(Example 23). However, in the piano reduction of the work, in spite of the

relative homogeneity of the sound of the lines played by only one instrument,

the pointillist quality is still clearly audible. This is the first

introduction of pointillist piano writing which will recur in much of the

composer’s subsequent works for this instrument (Example 24).

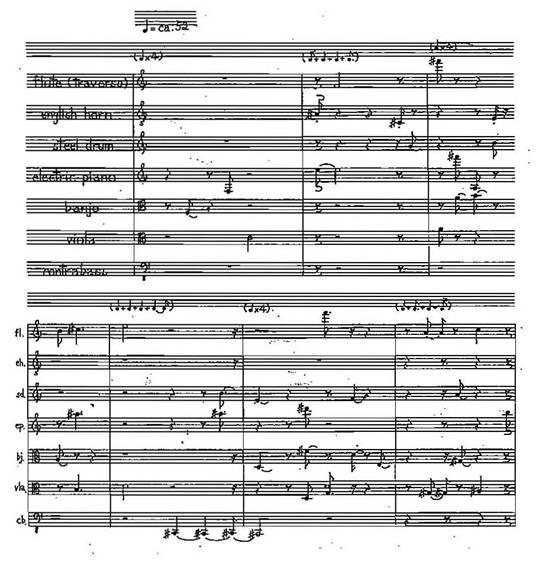

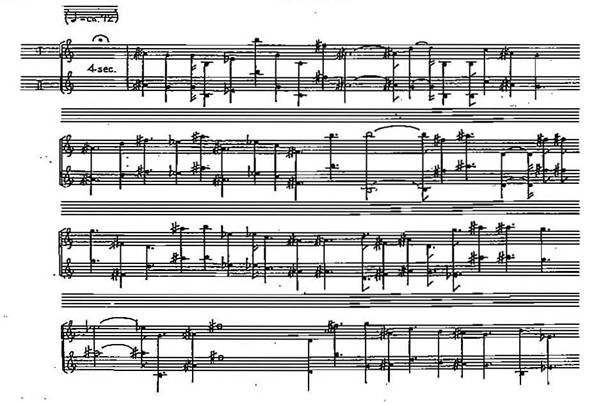

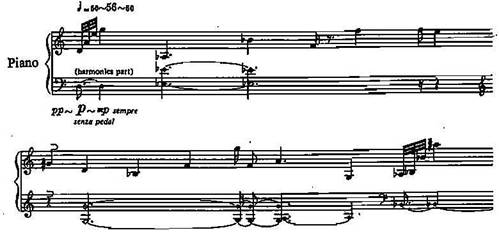

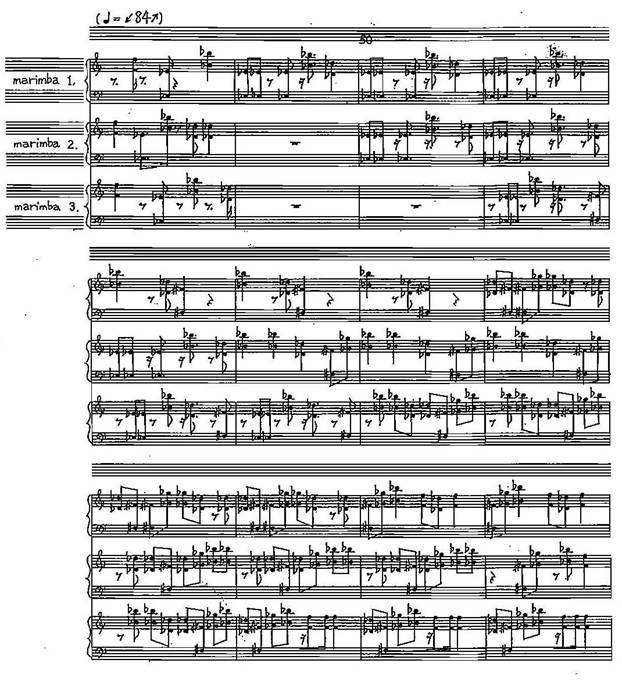

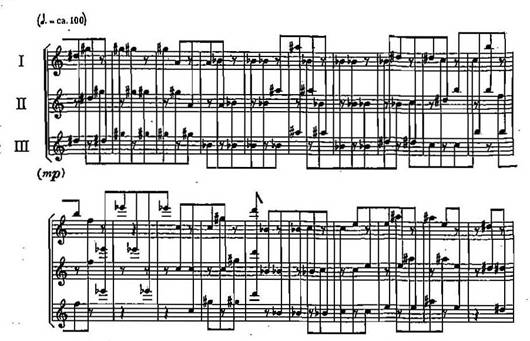

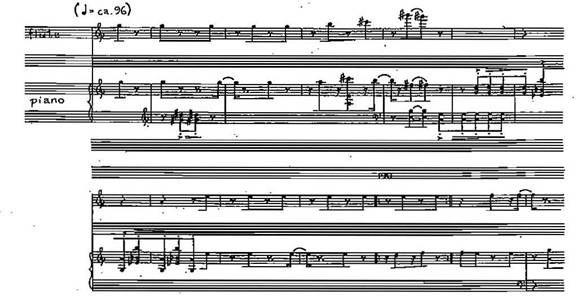

Example

24:

Pointillist Melodic Style, Sight Rhythmics (piano version): fourth

movement, page 4, sixth and seventh systems

Example

23:

Pointillist Melodic Style, Sight Rhythmics: fourth movement, page 8,

measures 22 – 27

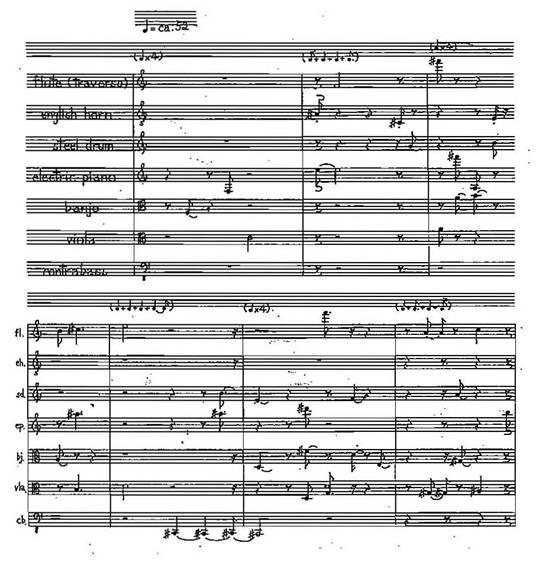

Example

25:

Pointillist Melodic Style, Strands I: page 4, second system

Strands I can be considered

a sister piece to the ensemble version of Sight Rhythmics due to the use

of three of the same rather unconventional instruments (steel drum, electric

piano and banjo), and its identical pointillist melodic style (Example 25). When

Wind Blew, written for a slightly larger ensemble, also employs pointillist

melodic style throughout the composition in the manner shown above (Example

26).

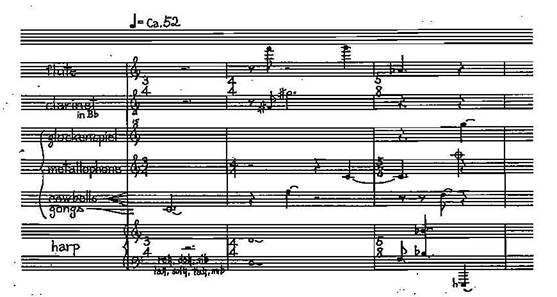

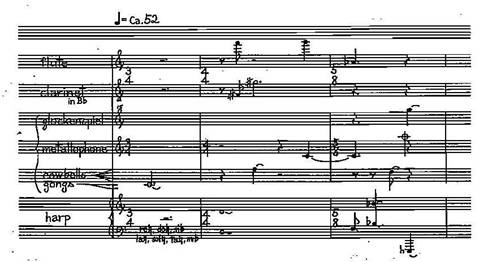

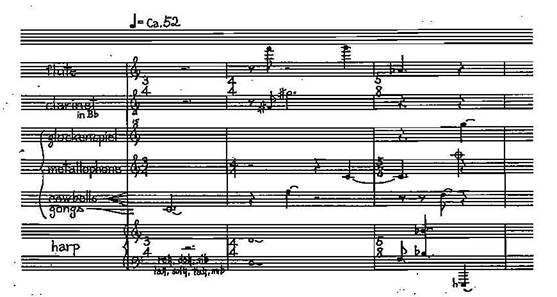

Example

26:

Pointillist Melodic Style, When Wind Blew:

page 2, measures 4 – 10

The

pointillist writing seen in An Insular Style is restricted to the

percussion and harp parts, with the upper two voices (flute and clarinet) being

written in a more conventional style (Example 27).

One of the

most important aspects of Kondo’s pointillist melodic style is how it

contributes to the autonomy of single tones. As can be seen in all the examples

above, single tones are clearly audible as single entities sounding alone in a

completely non-contrapuntal texture. Yet they are also connected to each other

in melodic groupings “which is precisely the syntactic device I [Kondo] use to

bind the individual sounds together.”

These examples above are representative of Kondo’s idea of the “melodic prism”

through which the listener perceives the individual sounds within a clear melodic context. The use of a pointillist melody-like

structure throughout a work encourages a more active form of listening to

individual sounds as the listener is never quite sure how, and in which voice,

the melody will proceed.

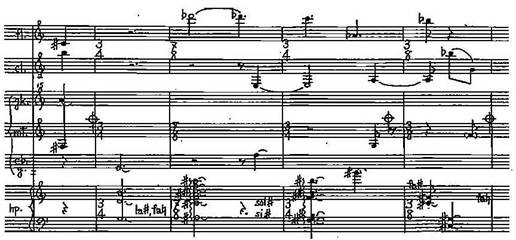

Example

27: Combination

of Pointillist and Simple Melodic Styles, An Insular Style: page 2,

measures 9 – 12

Example

28:

Falling: page 3, first system

In some sen

no ongaku compositions, the line on which the composition is based is

masked to varying degrees, making it somewhat difficult to assign it to any

specific melodic category. In the work Falling,

for example, the extremely elongated line played by the electric piano is

overshadowed by the more prominent glissando texture of the three string

instruments (Example 28).

In the

case of Pass, the banjo line while clearly audible, is also somewhat

obscured by the other four instruments which form a pointillist counterpoint to

this line. Example 29, which is representative of the work as a whole, is

heard more as a four-part texture than a single line with shadow notes. The

main line of the banjo is “almost buried” in the texture of the “independent

structure that could almost be called a figure for each instrument.”

Example

29:

Pass: page 3, second system

In Threadbare

Unlimited, as a result of the dense harmonic texture, the original line

in the top voice is veiled to such an extent that it cannot be clearly heard at

all times (Example 30). In spite of the inaudibility of this line, we know from

Kondo’s words that the work is based on a single line as he explains it as his

“first timid attempt to apply somehow this kind of compositional methodology [Sen

no ongaku] to thicker materials.”

The work

An Insular Style is rather exceptional in Kondo’s oeuvre in that it is one of

the few compositions to employ conventional sounding melody which the composer

describes as “...more clearly articulated and less abstract than in most of my

works. Its melodic contour or phrase structure appears to be closer to

conventional melodic writing, and therefore more accessible to the listener.”

While the

melodic writing in this work most closely conforms to the stylistic category of

simple melodic style, it is somewhat different due to its very clear phrase

structure with definite points of cadential closure. In order to highlight the

difference between the quite similar simple melodic style and conventional

melodic style, an excerpt from Orient Orientation (Example 31) is

compared with an excerpt from An Insular Style (Example 32).

Example

30:

Threadbare Unlimited: page 9, measures 119 – 127

Example

31:

Orient Orientation: page 4, first and second systems

Example

32:

An Insular Style: page 4, measures 39 – 42

The melody

of Example 31 is continuous, with no clear breaks in phrasing. This melodic

fragment can be interpreted in various ways depending on how each individual

listener groups these notes into melodic figures. We could call this pseudo-melody. The flute

and clarinet lines in Example 32, however, strongly resemble conventional

melody as they are articulated in clear melodic phrases.

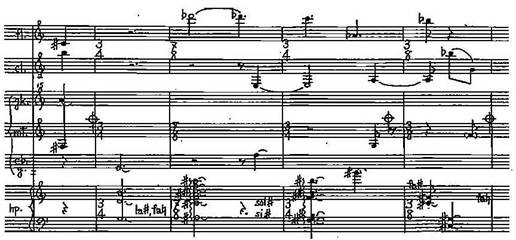

Looking at

another example from An Insular Style we can see that the melodic

figuration of the clarinet and flute are clearly independent from the

percussion and harp parts, which form an accompaniment to the two upper voices

(Example 33).

Example 33: An

Insular Style: page 3, measures 22 – 25

Example 33

clearly shows the dual function of the harp and percussion parts, on the one hand

as an accompaniment, and on the other hand as independent melodic figures. The

melodic aspect here is strengthened by the closeness of the melodic intervals. The

accompanying aspect is strengthened by the wide intervallic leaps and the use

of low pitches in the harp part. Occasionally, the harp and percussion writing

is strongly melodic, on almost equal footing with the upper two voices as in An Insular Style: page 4, measures 39 –

42 (see Example 32 above).

An Insular

Style is written in a subtle combination of pointillist and conventional

melodic styles with the harp and percussion relegated for the most part to an

accompanying role in pointillist melodic style. Conventional melodic style as

seen in this piece rarely surfaces in Kondo’s sen no ongaku music. When

it is employed, it is always combined with another melodic style.

Rhythm and

Meter

As we have

seen through the analysis of Orient Orientation, rhythm plays a very

important role in contributing to the autonomy of single tones. Asymmetrical

rhythm also creates the particular non-teleological, jagged continuity,

characteristic of all sen no ongaku works. However, this is not to say

that all of Kondo’s sen no ongaku compositions are written using

asymmetrical rhythm only. In some pieces, a very symmetrical rhythm is employed

in the form of a steady continuous pulse. These works share some affinities

with American minimalist music in their continual repetition of small cells of

pitch material over the entire composition, their relatively unchanging dynamic

texture, and their complete lack of sectional contrast and musical depth.

The three

works in the period 1973 to 1980 which conform to some minimalist

characteristics include Standing (1973) (Example 34), Luster Gave Her

the Hat and He and Ben Went On Across the Backyard (1975) (Example 35) and An

Elder’s Hocket (1979) (Example 36). In these three compositions, a

generally symmetrical rhythmic pulse is strongly prominent.

Example

34:

Standing: page 2, second system

Example 35

employs a single tempo, dynamic and texture throughout the composition. While

the eighth-note pulse is more or less constant throughout the entire work,

small sections are defined by slightly different rhythmic variations as can be

seen in the three systems of this example.

The

excerpt from An Elder’s Hocket (Example 36) is representative of

the work as a whole. As in the previous two examples, an eighth-note pulse is

clearly audible throughout the entire composition. The use of occasional

hemiola (the syncopated notes of the first beat of measure 71 and the last

beats of measures 87 and 89) adds some slight rhythmic variation at certain

points in the composition. But the use of this hemiola here, due to its

relative infrequency, has an ornamental function and does not shift attention

away from the steady eighth-note pulse.

Another

work employing a regular rhythmic pulse, which extends the technique of tied

note syncopation seen above even further is Walk for piano (1976)

(Example 38). Syncopation is used in Walk in a structural, rather than

ornamental manner. It is used so frequently in this work that the eighth-note

pulse is almost unrecognizable at times, with the rhythmic stress continually

shifting in an irregular manner over the course of the entire work.

In Example

37, within the space of only three systems, a great amount of rhythmic

variation can be found. The eighth-note pulse predominates in the first measure

of this example, but after entering the second measure, with the introduction

of the sixteenth-note on the second half of the second beat, the pulse is

interrupted. The eighth-note rest in the beginning of the third measure also

interrupts the eighth-note pulse. Syncopation is introduced again in measures

4, 5 and 6. The syncopation in bar 6 is very prominent due to its rather

extended duration of a dotted quarter-note. This extended duration has the

effect of almost terminating the sense of the eighth-note pulse.

Example

35: Luster

Gave Her the Hat and He and Ben Went On Across the Backyard: page 5, measures

48 – 59

Example

36:

An Elder’s Hocket: page 5, measures 71 – 89

Example

37:

Walk (piano version): page 4, first, second and third systems

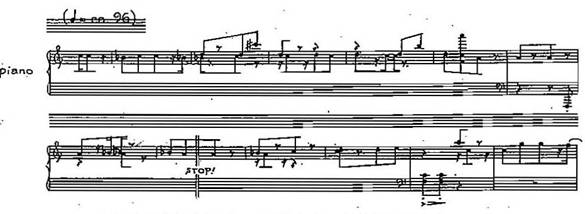

Another

interesting technique used by Kondo in this work to interrupt the continuity of

the eighth-note pulse is an instruction to stop suddenly in the middle of a

measure (see Example 38). It is the structural syncopation described above in

Example 37, along with the use of these fermata-like stop instructions shown in

Example 38, that set this work apart from the three works employing a more or

less steady pulse throughout the composition.

While the steady eighth-note pulses, although fragmented, are clearly

audible in Walk, the continuity of this composition is less periodic

than that of Standing, Luster Gave Her the Hat and He and Ben Went On

Across the Backyard and An Elder’s Hocket.

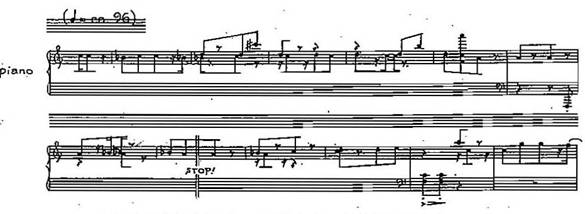

Example

38: Walk (piano version):

page 1, third and fourth systems

In spite

of the differences in style between Walk, Standing, Luster

Gave Her the Hat and He and Ben Went On Across the Backyard and An

Elder’s Hocket, all four works conform quite readily to five of the six

essential features of sen no ongaku style introduced on p.83 of this

study. Only one feature, the consistent

use of asymmetrical rhythm throughout a composition, does not apply to the

above four works.

In Standing,

Luster Gave Her the Hat and He and Ben Went On Across the Backyard and An

Elder’s Hocket, there are few explicitly recognizable rhythmic patterns. In

these three compositions written in uni-sectional static form, Kondo created a

dynamically and texturally uniform rhythmic field in order to experiment with a

new manner of listening that allows for multiple interpretations of rhythmic

groupings.

In the

case of music written in a single unchanging pulse, the only way groupings can

be perceived is through stress or emphasis of certain notes in relation to

others.

Kondo does in fact often employ stress at various points throughout the three

compositions above, but this stress is very irregularly placed creating

rhythmic ambiguity, which in turn, encourages multiple interpretations of

specific rhythmic groupings. Of the three works above, Standing treats

the link between rhythmic ambiguity and listening in the most sophisticated

manner. In this work, due to the delicate balance of various

asymmetrical rhythmic patterns, the listener is often at a loss as to where a

particular rhythmic pattern or melodic phrase begins or ends. The deliberately

ambiguous rhythmic groupings allow for a very rich listening experience in

which the listener is pleasantly disorientated throughout most of the work. Of

all the early sen no ongaku works, Standing most singularly

exemplifies the composer’s aesthetic intentions. This work was one of the last

to employ a pre-composed chart of random numbers assigned to a gamut of sounds

to decide the pitch content of the melodic line throughout the composition

(Example 39).

Example

39:

Gamut of Sounds Used for Standing

Due to the

biased distribution of sounds resulting from the random method of choosing his pitches,

an overall

quasi-modal (or ‘tonal’) flavor permeates the melodic line, since the biased

distribution of sounds emphasizes some specific pitches at the expense of

others, with the result that some of them almost sound like nuclear tones (or

even tonics) in a tonal composition.

After

generating the material of the work using random procedures, Kondo then deleted

any portion of the row which “was too obvious or too vague in its tonal feeling

so as to obtain the right degree of tonal ambiguity.”

It is important to note the composer’s decision here to combine a systematic

method of composing with an empirical one based on his own listening.

In the

beginning of the work from page one to the middle of the last system of page

three, the melody is distributed among the three voices employing the shadow technique

as seen in Example 40. From the last system of page 3 the texture becomes more

complex due to the overlapping of two rows creating harmony in the form of

two-note chords as seen below.

Example

40:

Two-Part Texture in Standing: page 4, first and second systems

Here in

the first system of Example 40, the pulse is just as metrically regular as Example

34, but the stress is less clear with the “feeling of triple time”

completely obliterated due to the very irregular groupings of tones into groups

of two, three or four repetitions of a single pitch. In the second and third

measures of the second system of this example, the insertion of a single

measure of material written in the same style as the earlier triple time

section serves to jog the listener’s memory by briefly re-establishing the

triple time grouping.

Another

rhythmic variation used in Standing to interrupt the continuity of the

eighth-note pulse is shown in Example 41. Here, from the third to the seventh

measure, a change in tempo is achieved by inserting rests between notes. The

separation of the notes by quarter-note rests stresses the feeling of triple

time.

A very

brief tempo change in the first three bars of Example 42 is achieved by the

insertion of eighth-note silences between the sounding pitches. In this case, a

duple time feeling is created.

Example

41: Tempo

Shifting Through the Insertion of Rests in Standing: page 7, fourth system

Example

42:

Tempo Shifting Through the Insertion of Rests in Standing: page 5, third system

Another form

of variation by rhythmic diminution (from eighth-note to sixteenth- note pulses) appears in an extended section

of the work from the fourth system of page 15 to the third system of page 18. An

example of this texture is shown in Example 43.

Looking at

the placement of these sixteenth-note figures over the whole example, we can

see that in the first system, the sixteenth-note figures are placed in an

asymmetrical manner. In the second and third systems however, they are placed

in a symmetrical manner in order to emphasize the feeling of triple time.

Rhythmic ambiguity in Standing is achieved through the horizontal and

vertical juxtaposition of these small rhythmic cells of various durations.

It is this

balance between regularity and irregularity, an idiosyncrasy of all sen no

ongaku works to follow, that gives this composition its essential musical

shape and characteristic jagged continuity. Kondo’s primary intention here is

to create a musical environment which leaves the listener “enough leeway to

decide the groupings by himself”

to allow for an interpretation of the groupings different from the way the

composer might hear them.

Example

43:

Rhythmic Diminution in Standing: page 17, first, second and third

systems

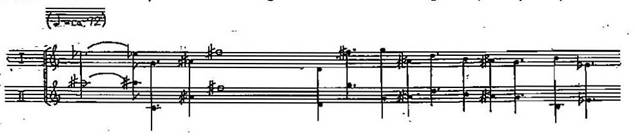

A New

Rhythmic Notation

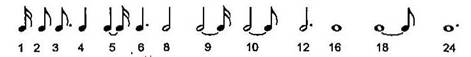

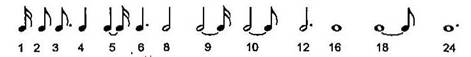

In 1973

with the composition of Click Crack (1975) Kondo introduced a new

rhythmic notation (Example 44) to express a non-bipartite value in a clear

manner. This notation first appears in Click

Crack.

Example

44: Rhythmic

Notation and Usage in Click Crack: page 1, second system

In conventional

notation, the above expressions of one third or two thirds of a beat or rest

can only be accomplished by using the closest rhythmic value in a symbolic

manner. Kondo’s new notation is very

close to an earlier example of a new notation created by Henry Cowell to

reflect irregular note values. Cowell explains his new notation in the

following manner:

Still

another possibility opened up by the new notation is that of separating notes

of triplet or other time values by placing between them notes of other

systems. Thus in old notation three

triplet notes or their equivalent must always be used together; in the new

notation perhaps only one triplet note will be used between quarter notes,

While Cowell’s

1/3 note in the above example does not have complete independence in the same

manner as Kondo’s notation, Cowell’s quote seems to suggest that he was aware

of the possibility of the complete independence of such a figure in the future.

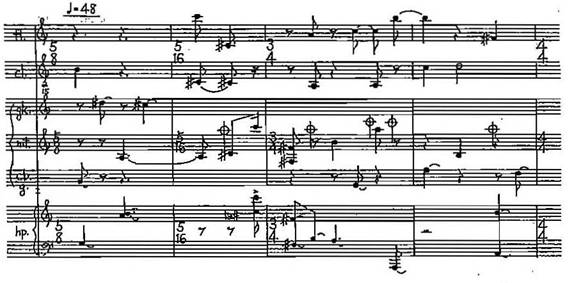

In the period

1973 – 1980, the following works use Kondo’s new notation: Click Crack

(1973), Pass (1974), Sight Rhythmics (both versions) (1975), Retard

(1978), Strands I (1978) and Strands II (1980). Although this notation was not used in works

written for large ensembles up to 1980, after this date, with the move towards

complexity, we can find this rhythmic notation used in a much more intricate

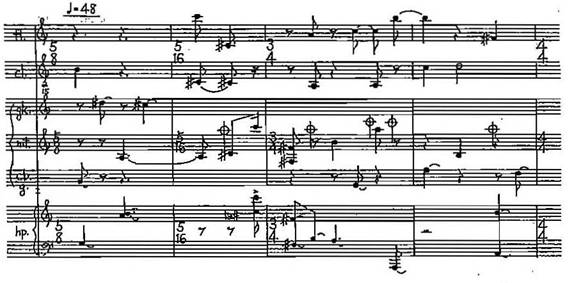

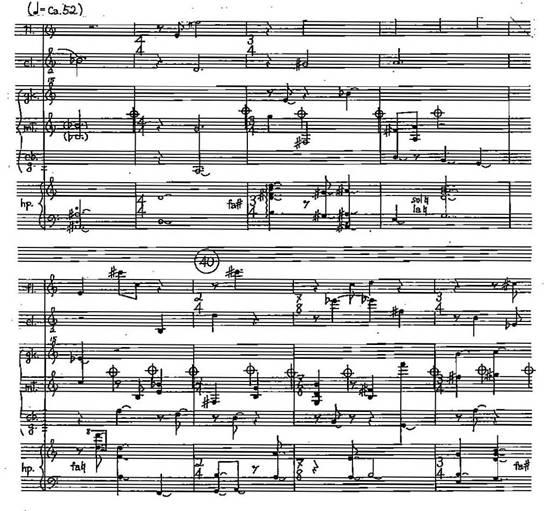

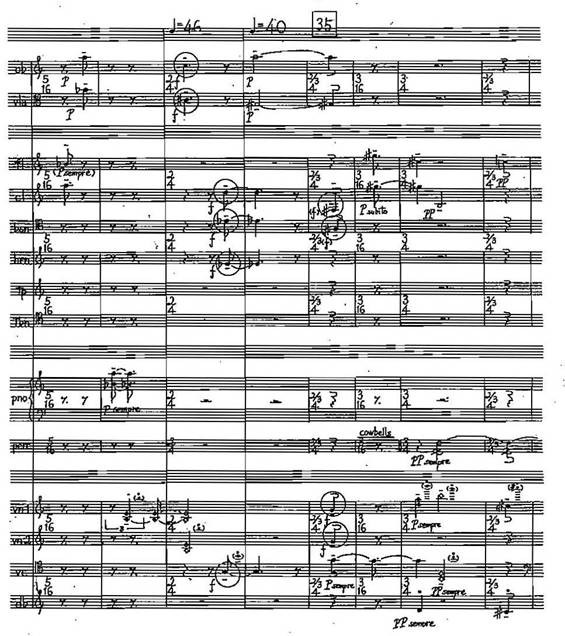

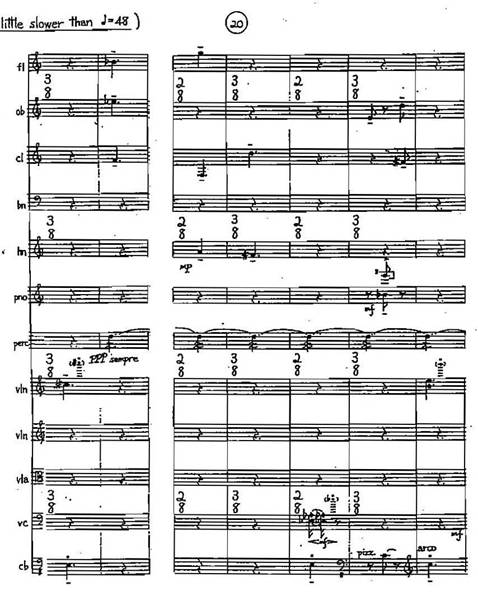

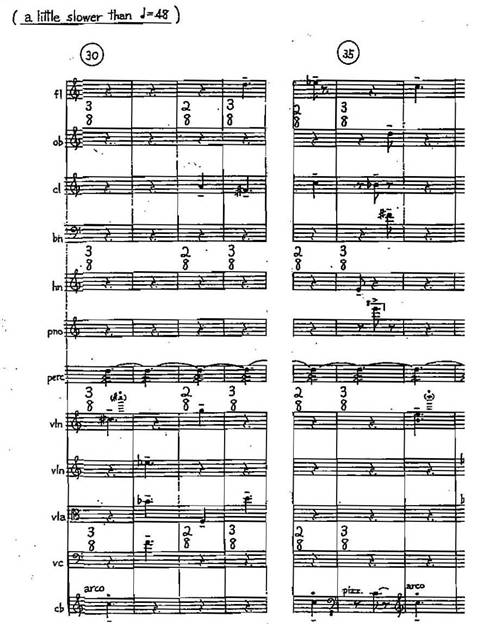

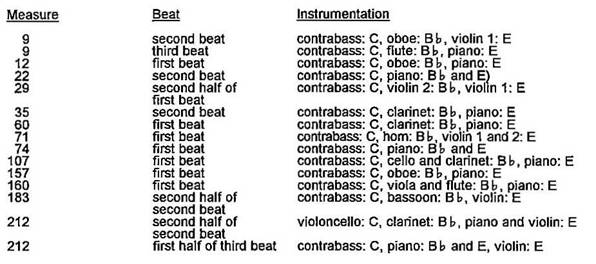

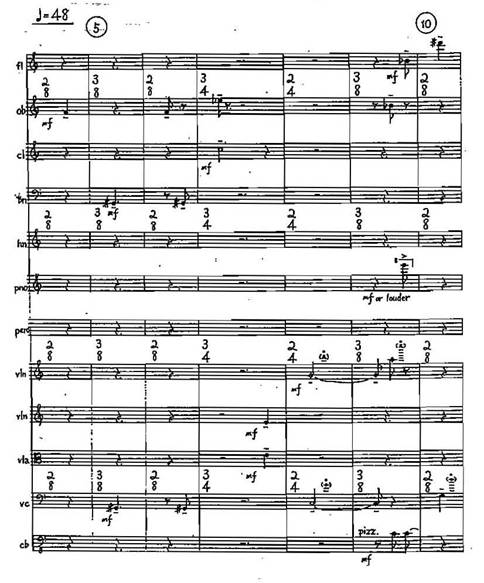

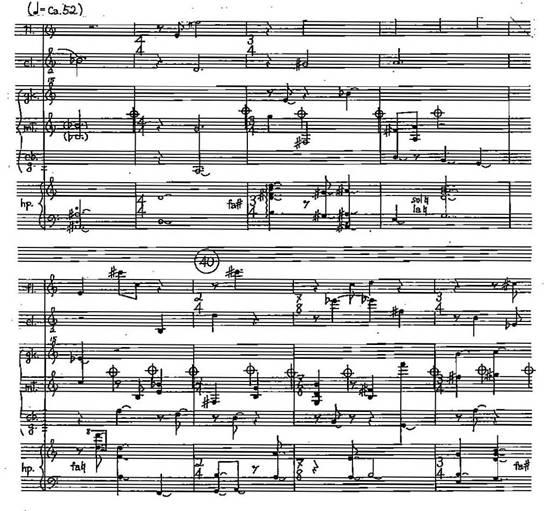

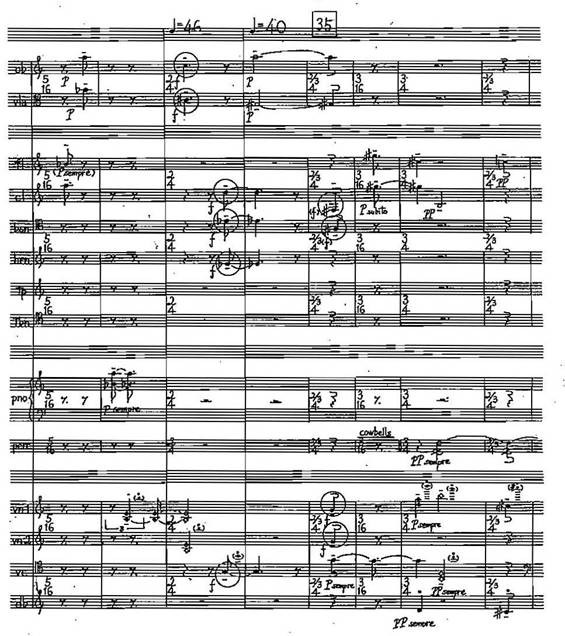

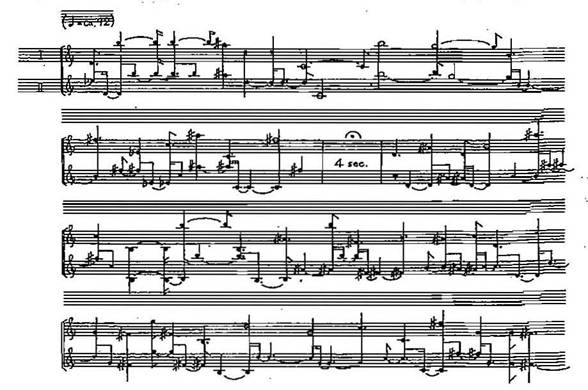

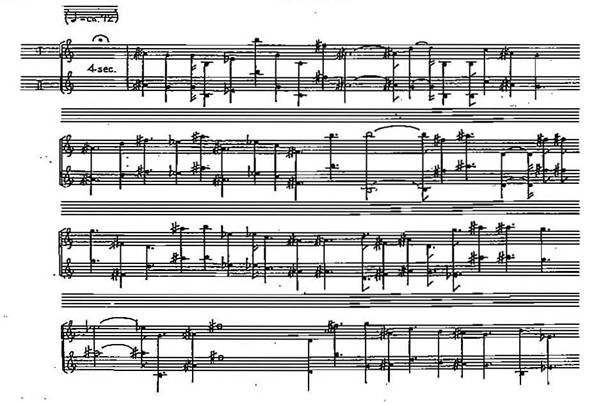

context in Res sonorae (1987) (Example 45).

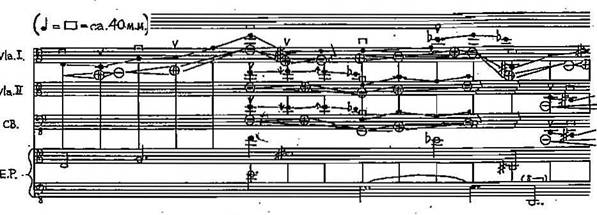

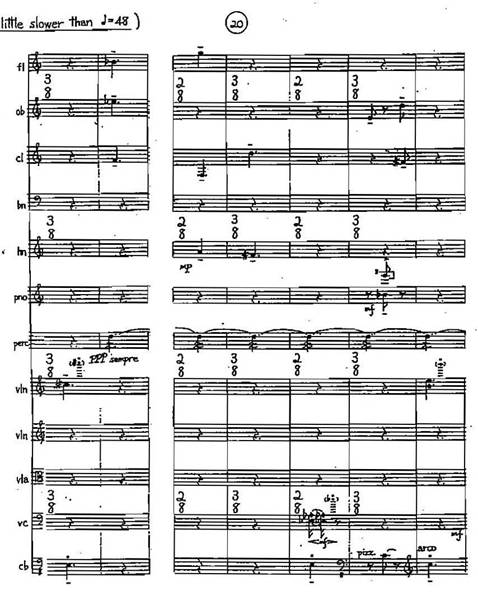

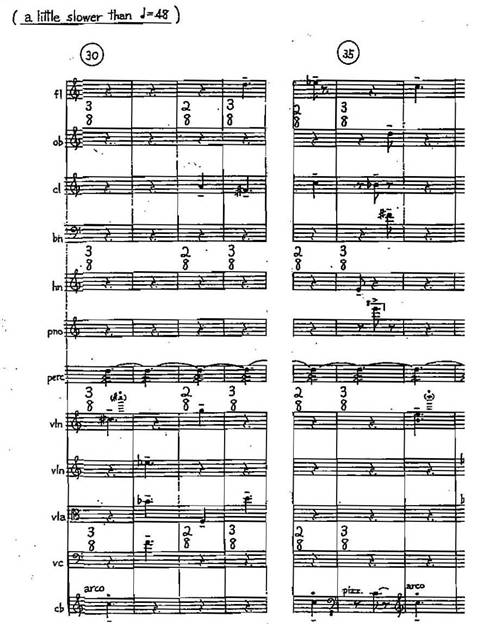

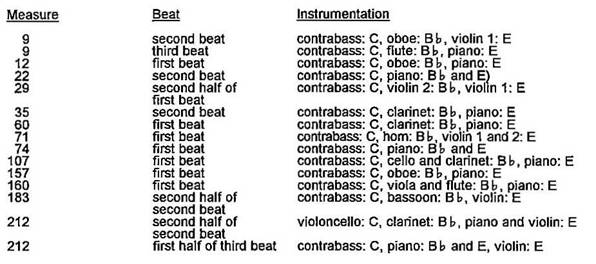

Circles in

Example 45 are dynamic indications written by the composer. The use of the new

rhythmic figure occurs in measures 35 and 38.

In general Kondo restricts the use of this notation to chamber works of

two to five instruments, but here it is used very effectively in an ensemble of

fourteen players.

Vertical Formations

With the

exception of The Shape Follows Its Shadow (1975), Threadbare

Unlimited (1979) and A Shape of Time (1980), vertical formations in the

works written in the period 1973 -1980 generally consist of two-note chords. These

two-note chords have no relation to functional harmony and can be considered as

simply colorings of single tones. These

harmonic colorings (explained in detail in the analysis of Orient

Orientation in Appendix A) occasionally expand to three-note chords as seen

in Knots (1977) (Example 46). The consistent use of rhythmic unison in

this excerpt, helps to maintain a balance between linear and harmonic elements.

In the case

of Click Crack, vertical formations of four or more notes are written in

the form of the barely audible piano harmonics (Example 47).

Example

45:

Res sonorae, page 5, measures 31 – 38

Example

46:

Knots: page 7, first and second systems

Example

47:

Click Crack: page 4, fifth and sixth systems

Vertical formations

sometimes appear suddenly for slight textural contrast as seen in the work Walk

for flute and piano (Example 48).

Example

48:

Walk: (flute and piano version) page 8, first and second systems

Chords in Walk

are treated in the same way as single pitches, appearing in a hocket-like

manner to emphasize the linear movement of the eighth-note pulse. Any potential connections to functional harmony

are considerably weakened by this clear emphasis of rhythmic over harmonic

relations.

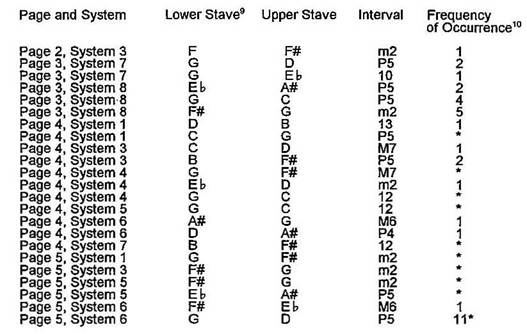

The use of

particular intervals throughout a single work, determines to some extent, the

atmosphere of each of Kondo’s compositions. In general, most of the intervals

making up the harmonies used in the works composed form 1973 to 1980, are consonant

or mildly dissonant. Preferred intervals include: the major second, minor and

major thirds and the perfect fourth and fifth. Vertical formations made up of

three, four or more notes are also employed in the works The Shape Follows

Its Shadow, Walk, An Insular Style and A Shape of Time. The

consistent use of relatively consonant intervals and chords contributes to the

diatonic or modal sounding atmosphere of the works composed in this period. From

the composition of Strands II at the end of 1980, the preferred

intervals are much more dissonant, with minor seconds, major sevenths and minor

ninths replacing the more consonant intervals of the earlier period (Example 49).

This

discussion of vertical relations will close with a discussion of An Insular

Style, a piece which in the composer’s words is “rather exceptional in this

linear style of mine,”

due to the use of conventional melodic writing and tonal harmony. Continuing he

states: “Harmony, although not supporting the melody line in a traditional

sense, but just ‘shadowing’ that line to give it some coloring, is more unambiguously

tonal than usual. Altogether, An Insular Style may sound much like a

folk tune from an (imaginary) island.”

Example

49:

Strands II: page 7, third, fourth and fifth systems

Two

factors contribute to the “unambiguously tonal” sound world in this work. These

are conventional melodic writing in the upper two voices and the use of particular

consonant intervals. One rather traditional aspect of this composition not

found in earlier sen no ongaku works is the assigning of specific

functions to the four instruments, with the flute and clarinet playing

melodies, and the harp and percussion assigned to an accompanying role for the

most part (Example 50). Here the harp has the clearest accompanying role by

playing chords and single pitches in its lower range. The accompanying role of

the percussionist is not felt as strongly as the harp’s, because the chords are

played simultaneously on two instruments of very contrasting timbres. The

indefinite pitch of the cowbells also weakens somewhat, the sounding of clear

harmonies. Compared to the harp, which has the specific role of grounding the

harmony, the percussion accompaniment has a more coloristic role.

Example

50:

An Insular Style: page 10, measures 110 – 114

Tonal harmony is strongly suggested

by the frequent use of consonant intervals and triadic harmony throughout the

composition (Example 51).

Example

51:

An Insular Style: page 1, measures 1 – 3

The third measure

of Example 51 serves as a clear example of how tonality is emphasized through

instrumental range and particular choice of intervals. The tonal harmony is

reinforced by the range of the harp, with the low E flat (functioning here as a

tonic), being played in combination with a very high G (3rd) in the

glockenspiel part. The harmony here is strengthened even more as the preceding

B flat and F in the harp part (which resonate through the entire bar) complete

an E flat chord.

The

occasional use of arpeggios in the harp part also strengthens the

harmony by drawing attention to the quasi-tonal chordal formations played

(Example 52).

Example

52:

An Insular Style: page 7, second half of measures 71 – 75

While this

work employs very tonal materials, it must be remembered that they cannot be

classified in terms of functional tonality.

In spite of the rather conventional melodic writing in the upper two

voices, the melodic notes for the most part align rhythmically with other

voices creating what the composer refers to as “the linear character of many of

my compositions, written almost entirely as a single, continuous melodic line,

accompanied by some harmonic coloring of the notes that make the main line.” While the principles of sen no

ongaku are still clearly adhered to, a new melodic freedom and emphasis on

tonal harmonies can be found in this somewhat atypical composition.

Structure

and Form

The single

most important aspect of Kondo’s style, namely, its linearity, has been treated

in detail up to now. While almost all of

Kondo’s compositions from 1973 to the present can be said to be “consistently

centered on ‘static form’¼ and on

the concept of ‘linear music,’ music consisting of a single ‘melodic’ line,”

there are other elements of the style not yet addressed, which will be taken up

in this section. We will now widen our

lens to view the works in terms of their larger structures and overall form.

Most

compositions of the first period are written in uni-sectional static form. That

is to say, most works consist of one continuous, relatively uniform stream of

music, with little textural, harmonic and dynamic contrast. These works are:

Orient Orientation (1973), Standing (1973), Falling (1973), Click

Crack (1973), Pass (1974), The Shape Follows Its Shadow (1975),

Luster Gave Her the Hat and He and Ben Went Across the Backyard (1975), Walk

(both versions) (1976), Knots (1977), Retard (1977), Strands I

(1978), A Crow (1978), An Elder’s Hocket (1979), When Wind

Blew (1979), Threadbare Unlimited (1979), An Insular Style

(1980), A Shape of Time (1980) and Strands II (1980).

A few

works from the period 1973 to 1980 are structured in distinct contrasting

sections and therefore fall outside the category of uni-sectional static form. They

include: Mr. Bloomfield, His Spacing (1973), Wait (1973)

and Under the Umbrella (1976).

Sight

Rhythmics

One very

important work in Kondo’s oeuvre which hovers between the two formal categories

of uni-sectional static form and sectional form discussed above is Sight

Rhythmics (1975). This work is one of the few sen no ongaku

compositions involving separate movements. However, because these movements are

almost identical to each other, with very slight changes from movement to

movement, there is little sense of development over the course of the work. The

composition can almost be likened to a single stream of music with rests

inserted to occasionally break the continuity, in the same manner as Orient

Orientation (see Appendix A). We know from reading Kondo’s words that this

work was an important turning point in terms of how he treated form and larger

structural divisions: “It was from Sight Rhythmics that I consciously

started to search for ambiguities on the structural level that might

traditionally be called form.”

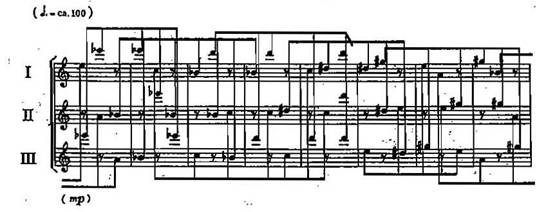

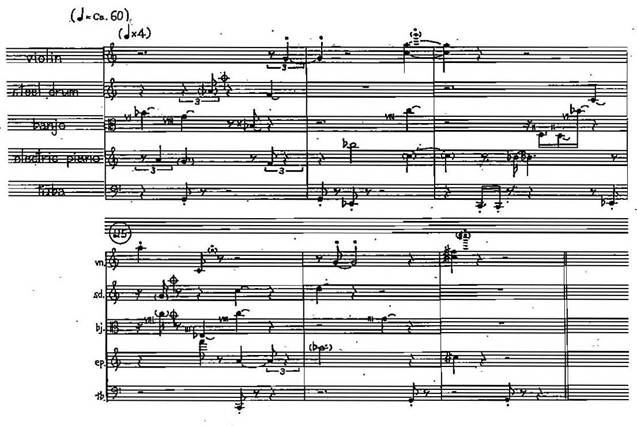

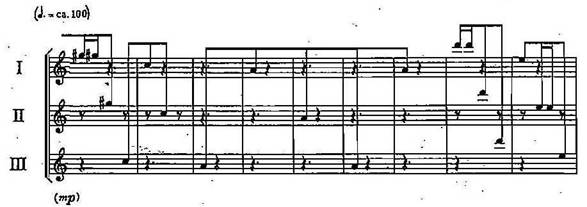

One of the

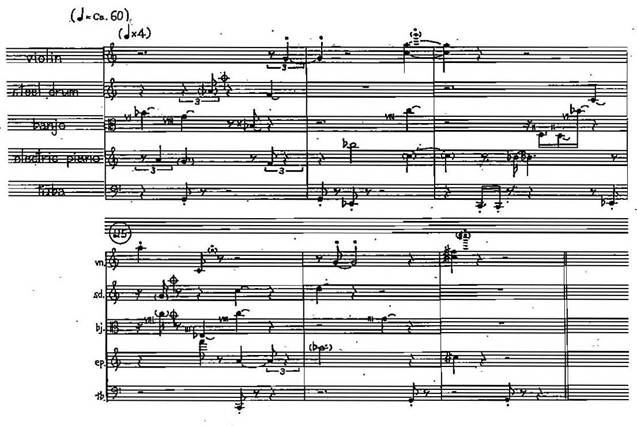

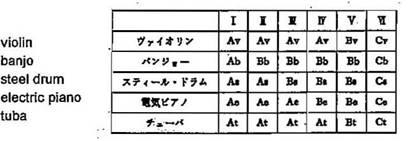

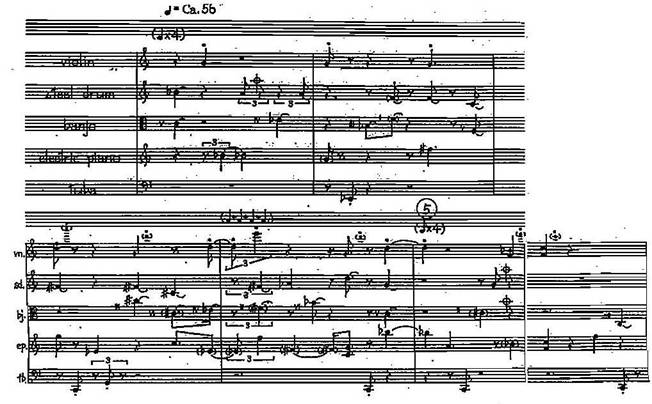

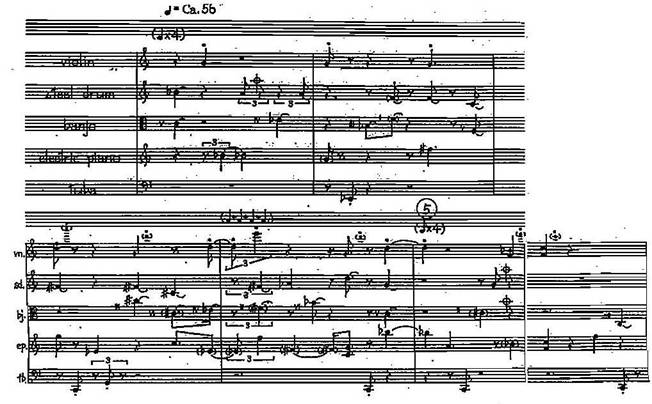

distinguishing features of the ensemble version of Sight Rhythmics (for violin,

steel drum, banjo, electric piano and tuba) is its unorthodox instrumentation. The

distinctive instrumentation of five completely dissimilar instruments was

chosen to emphasize individual sounds, as the timbres of these five instruments

do not blend so easily. Looking at the first seven measures we can see that

this work is written in pointillist melodic style with no real individual voice

independence (Example 53). Looking carefully, it can be seen that in spite of

the occasional overlapping of voices, for the most part, the texture consists

of a single line played in a hocket-like manner by each instrument in

succession. Due to the relatively close spacing of the notes of this line

(apart from the very low notes in the tuba and very high notes in the violin)

it can be quite readily distinguished by the ear.

The

individual voices of each instrument cannot be said to form continuous lines in

the manner of a clear instrumental part because of the continual breaks in

continuity. However, due to the extremely distinctive timbre of the

instruments, the ear has little difficulty in following each instrumental

voice. In the example below the tuba notes are the most obviously audible,

forming a kind of bass accompaniment to the upper voices. The violin voice is

also clearly audible due to the high range of the harmonics and the restriction

to only two pitches, like the tuba. The steel drum and banjo parts tend to

overshadow the electric piano voice, but if one chooses to focus attention on

the electric piano only, most of this part is also clearly audible due to the

frequent sounding of notes in complete isolation.

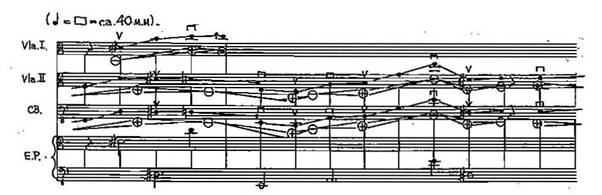

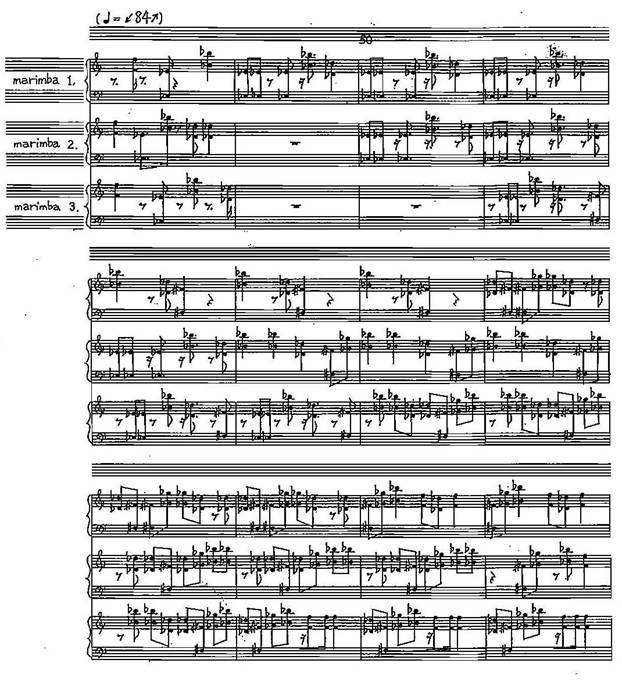

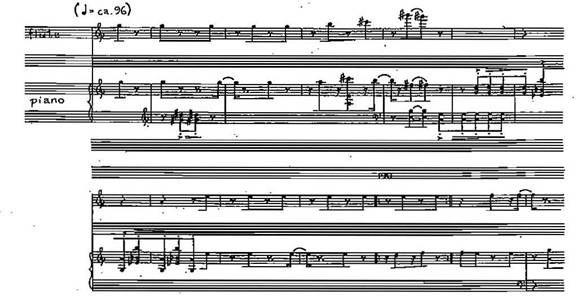

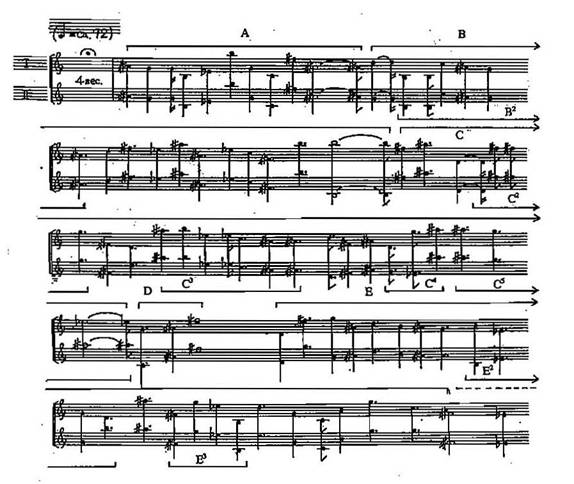

Example

53: Sight

Rhythmics:

movement 1, page 1, measures 1 - 6

Melodic

structure in Sight Rhythmics is rather ambiguously implied in order to

suggest multiple readings. When listening to this work the ear tends to

vacillate between various points of focus. The listener might follow the flow

of the melody from instrument to instrument for a few bars and then later be

drawn to a distinctive pattern (or pulse in the case of the tuba and violin

parts) in a single instrumental voice. As in all sen no ongaku works of

this period, note groupings are not explicitly expressed, allowing for various

interpretations depending on the predilection of the individual listeners.

Kondo explains this ambiguous application of note groupings in Sight

Rhythmics in the following manner:

¼ there is a

melody-like structure, but it is never unambiguously established; it is almost

a melody, yet not quite. The listener

can feel that a melody-like structure exists (which is precisely the syntactic

device I use to bind the individual sounds together), but he is still able to

recognize each individual sound in its own right.

When

composing this work, Kondo was interested in touching on a particular problem

inherent in ensemble playing, in which performers are required to play

individual parts (which are incomplete by themselves) in a collective manner to

realize the whole. Kondo used the Japanese term “sanso” (literally,

scattered playing) to describe this performance practice.

This term relates to one of Kondo’s most important aesthetic concerns, namely,

“that in music each sound has to have its own entity and life.”

Sight

Rhythmics

is divided into six movements. The first five movements are of exactly equal

length and sound almost identical. The final movement, as the subtitle

“SCHOLION” suggests, functions as a kind of appendix to the work. However,

because the texture, pitch material and hocket-like phrasing of this final

movement are almost identical to the preceding five movements, it acts as a

very subtle closing to the work.

Because of

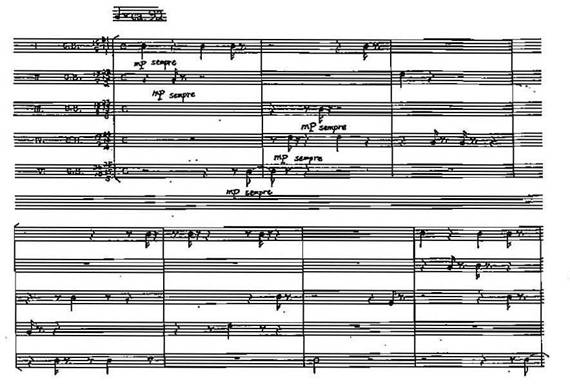

the very slight alteration of material in the first five movements of Sight

Rhythmics (only one instrumental part changes from movement to movement)

there is a clear lack of development but a definite sense of change over time,

although it is somewhat difficult for the listener to pinpoint concretely where

this change occurs. Kondo termed this

very subtle change from movement to movement “pseudo-repetition” which “is

almost as static as literal repetition, but at the same time becomes a vehicle

for hidden change and movement.”

The

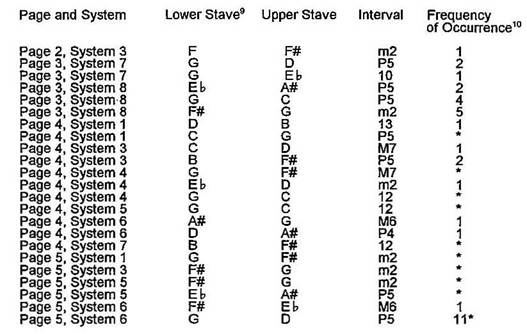

movement to movement changes in Sight Rhythmics are shown in the

following chart in Example 54. The capital letter A signifies original

material, B signifies alteration of the original material, and C signifies

completely new material. Lower case letters correspond to the first letters of

the names of the five instruments.

It can be seen

from looking at this chart that once a part changes it remains fixed in that state

until the final movement. Changes in this work are cumulative occurring gradually

from movement to movement Rather than

development, we can liken this to a very subtle organic growth. Kondo uses the

term “dynamic stasis” to describe this form of continuity and perception of

time: “We could liken the listener’s experience of dynamic stasis to the way we

experience our everyday life. Each day seems very similar to the previous one

(daily routine), but today is never exactly the same as yesterday.”

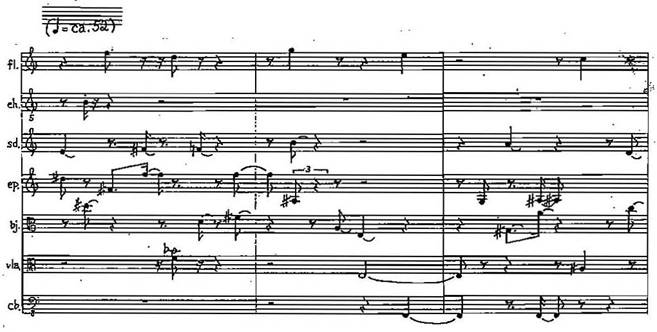

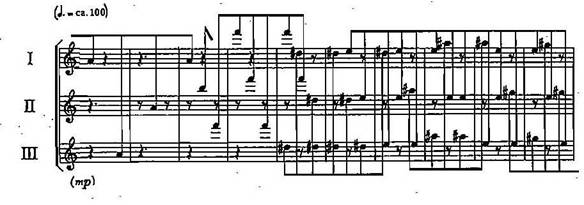

Viewing

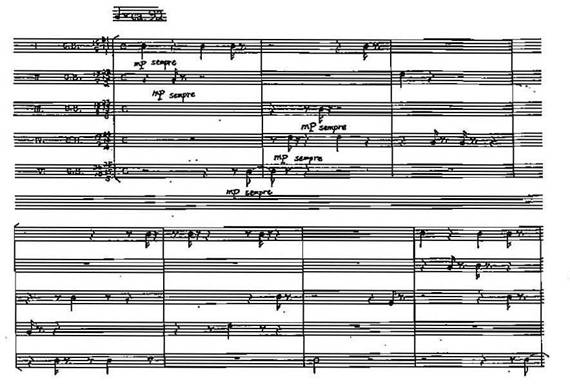

the work closely it can be seen that when parts change they are altered in a

very subtle manner with the altered line closely resembling and occasionally

duplicating the line of the previous movement. We can see the result of the

cumulative change over the course of the entire work by comparing the opening

measures of the first movement to the corresponding measures of the fifth

movement (Examples 53 and 55).

Example

55: Sight

Rhythmics:

fifth movement, page 11, measures 1 - 6

The

composition of Sight Rhythmics marks a very important transition from

early to mature sen no ongaku . It is here that the composer first

grappled consciously with problems of form.

In this work Kondo was interested in organizing material in distinctive

movements, to experiment with pseudo-repetition and dynamic stasis. For the

first time since 1973, the steady stream, uni-sectional static form of almost

all of the sen no ongaku works written up to this point, is abandoned in

favor of a new means of organizing the material of a single work in self-

contained movements thus broadening Kondo’s palette of structural and formal

devices.

While

there are no recurrences of “pseudo-repetition” using completely symmetrical

self-contained movements in future works, slightly different forms of

“pseudo-repetition” can still be found. Viewed in retrospect, we can see that Sight

Rhythmics was a kind of laboratory for Kondo to experiment with techniques

of “pseudo-repetition,” which could easily be transferred to works of larger

forces.

Under the

Umbrella

Under the

Umbrella

(1972) is a unique composition in Kondo’s oeuvre as it is the only work in

which the sen no ongaku method is applied solely to instruments of

non-standardized pitch.

The work is written for five performers, each playing five cowbells, with the

first performer also playing a low gong only at the end of the piece. Kondo specifies in the instrumentation of the

work that “25 graduated cowbells” are to be distributed equally among the five

performers in ascending order from the lowest to the highest sound in the

following manner: The first player: numbers 1, 6, 11, 16, 21 and a low gong;

the second player: numbers 2, 7, 12, 17, 22; the third player: numbers 3, 8,

13, 18, 23; the fourth player: numbers 4, 9, 14, 19, 24; the fifth player:

numbers 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25. This particular distribution was decided in

order to facilitate the rapid playing of adjacent pitches among all members of

the ensemble which would be otherwise be impossible for one player to execute.

The very

uniform sound world of Under the Umbrella represents a strong shift away

from the sound world of almost all previous sen no ongaku works. This work is written in four movements of

contrasting character which gives strong formal coherence to the composition.

The specific character of each of the four movements is created by variations in

tempo, texture and dynamics. This character is sustained throughout each

movement by being written in uni-sectional static form.

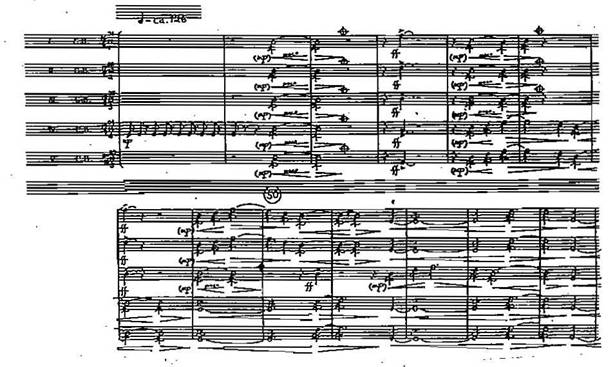

The first

movement, written in the quick tempo of q =126, is

characterized by the use of a driving

eighth-note pulse with frequent syncopation alternating between various

densities of vertical aggregates, from single pitches to five-note vertical

aggregates, as seen in Example 56.

Interestingly,

the rather sparse-looking score does not reflect the rich musical effect of the

rapid playing of the 25 graduated cowbells.

Although the cowbells are not fixed in standard pitches, the ear still

tends to group notes into melodic patterns in the same manner as other sen

no ongaku works of this period. That is to say that there is a very strong

sense of linkage from pitch to pitch. Other important aspects of sen no

ongaku style in works composed from 1973 to 1980 can also be found in this

movement. First, there is no dynamic contrast, with the entire movement being

played mezzo forte. Second, all

vertical aggregates are aligned in rhythmic unison with a clear absence of a

contrapuntal texture. Third, and most important, the music is written in a

continuous stream, without goal oriented movement or cadential closure.

Example

56:

Under the Umbrella: Beginning of Movement 1, page 1, first and second

systems

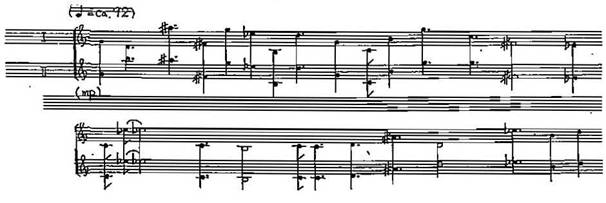

The second

movement bears close resemblance to the first in terms of its employment of

similar texture, but with some important differences. The slower tempo of q =

92 helps to contribute to the sounding

of each pitch or pitch aggregate as an isolated event rather than` a pulse, as

in the much faster first movement. The very sparse texture of this second

movement also allows the listener to focus on the timbre of each cowbell much

more clearly than the first movement. Combinations of cowbells here serve to

punctuate the quasi-melodic line played by single cowbells (Example 57).

In the

context of the work as a whole, the third movement is somewhat anomalous. It is most clearly distinguished from the

other three movements by the use of continuous tremolo playing with occasional fortissimo

attacks as seen in Example 58.

While the

first, second and fourth movements clearly fall under the category of sen no

ongaku style, the third, due to its frequent breaks in continuity, use of

sections written in a quasi-contrapuntal texture, and block-like construction,

falls out of the category of first period sen no ongaku compositions. We

can see in Example 58 a great amount of change from measure to measure which

contrasts sharply with the uni-sectional static form of the other three

movements. Here within the space of only twelve measures, there is a great

contrast in dynamics and articulation, along with clear breaks in the texture

which tends to fracture the continuity. In Example 59, also taken from the

third movement, we see a combination of textures very foreign to the sen no

ongaku style in the form of a short rhythmic figure played by the fourth

player followed by a rich vertical aggregate played by the full ensemble. This

kind of sharp contrast between measures of material of very different rhythmic

character is rarely found in the sen no ongaku works written between

1973 and 1980. It occurs only occasionally in much later compositions written

after 1987.

Example

57:

Under the Umbrella: Beginning of Movement 2, page 8, third and fourth

systems

Example

58:

Under the Umbrella: Beginning of Movement 3, page 13, first and second

systems

Example

59:

Under the Umbrella: Movement 3, page 14, third and fourth systems

The fourth and final movement of the work is written

in the fastest tempo of q = 152. The general

character of this movement bears strong resemblance to the first movement in

terms of its quick tempo, similar texture and the frequent employment of

syncopation alternating between various densities of vertical aggregates. Due

to its rather short duration in relation to the other three movements, and its

close similarity to the first, it almost functions as a kind of recapitulation

(Example 60).

One

important aspect all movements share, regardless of their quite contrasting

character, is the more or less consistent use of rhythmic unison. Rhythmic

unison here has the extremely important function of linking sound events of

similar timbre but non-standardized pitch. In the first, second and forth

movements, the rhythmic unison writing consists of rather short punctuations in

marked contrast to the long sustained tremolos of the third movement.

There is a certain logic

behind Kondo’s decision to write for the rather unusual ensemble of 25 cowbells

of graduated pitch. Had he opted to write for different non-pitched percussion

instruments, one of the composer’s most important concerns - that of preserving

the specific relationships between tones – would be lost. Because the cowbell

pitches are not standardized, we cannot speak of the relationships between them

in the same manner as standardized fixed tones, but they are nonetheless

clearly distinguishable from each other with each cowbell having a particular

identity, being of slightly different pitch and timbre. These 25 different

sounds are essentially equivalent to the composer’s gamuts employed in his

earlier works. Thus while there are almost twice as many tones used in Under

the Umbrella than the tones used for Orient Orientation (15 tones)

or Standing (12 tones), they are organized in essentially the same

manner, that is to say, all pitches are of equal importance with no particular

emphasis on any one as a central tone.

Example

60: Under

the Umbrella: Beginning of Movement 4, page 21, first and second

systems

Under the

Umbrella

is another extremely important work for Kondo as it afforded proof that the

principles of sen no ongaku could apply equally to standardized and