Hartmann’s

Fully-Chromaticized Scales

The Austrian theorist-analyst and

composer Friedrich Helmut Hartmann was clearly aware of von der Nüll’s work and

with regard to analyses of Arnold Schoenberg’s Drei Klavierstücke Op 11/1 (1909) and Max Reger’s piano work Aus meinem Tagebuch Op 82 (1904-1912) he

makes the following acknowledgement in his Harmonielehre

(1934), published two years after von der Nüll’s Moderne Harmonik:

The above comparisons (Schoenberg opus 11 and Max Reger opus 82)

are taken from the Moderne Harmonik of

this author [von der Nüll], whose excellent analyses were used on several

occasions in this book[9]

Thus,

it can be safely assumed that Hartmann doubtlessly had knowledge of von der

Nüll’s analyses of Bartók’s piano music and the theoretical base from which von

der Nüll developed these expanded, “supradiatonic” considerations.

The historical evolutionary process

pertaining to the organic growth of additional chromatic scalar members,

alluded to by Dallin, resulted in Hartmann’s[10]

formulation of the fully-chromaticized scales as:

indicative of the increasing knowledge that musical notes

and chords – hitherto considered as not belonging to the same key system – are

in fact members of the same key system, and governed by the same central power,

the system’s tonic.[11]

In

this idiom the harmonic palette is widened to include new harmonic colors and

tonal shadings with the shape of chord structures including constituent chordal

elements within the mold, reflecting the expanding harmonic vocabulary and

sound-world of this twentieth-century manifestation of tonality.[12]

Hartmann considered his fully-chromaticized scales as being guiding elements in

analysing twentieth-century tonal compositions:

…the term “expanded tonality” should be

used with regard to music employing the modern [fully-chromaticized] mixed

scale material [with the] melodic and harmonic applications characteristic of

it.[13]

The

composition of Hartmann’s fully-chromaticized scales and the historical process

with regard to the incorporation of chromatic notes has been delineated by

Socrates Paxinos:

The standard major scale added to its coloristic and

harmonic resources those notes from its tonic [natural] minor which the two

scales did not have in common. By a similar process, the minor scale was

likewise enriched with borrowings from its tonic major. To these were added

other chromatic notes, such as the Neapolitan second and the raised (or gypsy)

fourth.[14]

In

the fully-chromaticized major scale of C, for example, this justifies the

existence of five chromatically inflected notes: E♭,

A♭

and B♭

(added from the tonic natural minor), D♭

(Neapolitan second) and F# (Gypsy fourth). In addition five further

chromatically notated notes C#, D#, G♭,

G# and A# are the result of the historical process of either increasing

semitone support from above or below the seven diatonic degrees as explained by

Hartmann.

By systematic continuation of the chromatication [sic] of

the diatonic scales, that is by the insertion of semitones between all those

degrees of the pure major and minor scales which still are separated by

wholetone steps, the so-called fully chromaticized major and minor scales were

obtained.[15]

Thus,

the fully-chromaticized major and minor scales comprise seventeen constituent

members which through the nature of their design are an illustration of the

widening harmonic vocabulary and “sound-world” of twentieth-century expanded

tonality. Consider the following examples of the fully-chromaticized major and

minor scales with seven diatonic representations, five chromatically raised

degrees and five chromatically lowered degrees.

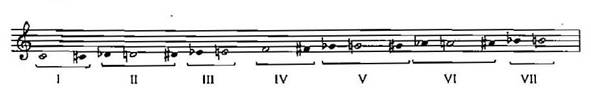

Example 1: Fully-chromaticized

major scale of C

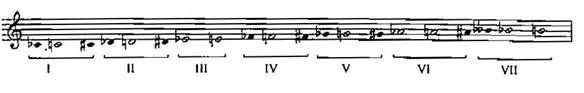

Example 2: Fully-chromaticized

minor scale of C

Hartmann (1956:20-21) has identified

the cumulative step in the historical evolution of the fully-chromaticized major

and minor scales as being the fully-chromaticized mixed scale. This scale is a

composite resulting from the fusion of both the fully-chromaticized major and

minor scales.

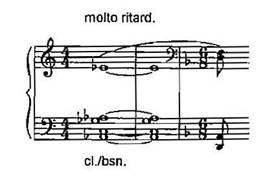

It is notated in the

following example and evidences no bias towards either the major or minor,

representing an amalgam of both major and minor modalities. Each degree is

represented thrice, except for the mediant degree, which possesses only two

representatives for this, the genus-defining degree. ‘What applies to man,

applies to music: there are only two genera’ (Hartmann, 1956:21).

Example 3: Fully-chromaticized

mixed scale on C

In

this way, the fully-chromaticized major and minor scales through the nature of

their design are indeed a reflection of the widening harmonic vocabulary and

sound-world of twentieth-century expanded tonality. The premises propagated

through Hartmann’s analyses reveal, how obscured diatonic tonal props and chord

functions within dissonantly constructed textures, are based upon the

tonicization procedures and harmonic syntax derived principally from the

Classic-Romantic continuum, with the diatonic and chromatic scalar members all

being dominated by the same, diatonic, tonic. In this regard the use of

Hartmann’s fully-chromaticized scales, in presenting specific formulae for

analyzing expanded tonal works, amplifies other analytical approaches,

especially those prevalent during his epoch.[16]

To this end, the analyses in this article are further proposed as a demonstration

of the viability, and in South African musicologist Bernard van der Linde’s

words, the “stroke of genius”[17]

of Hartmann’s fully-chromaticized scales in perceiving tonal coherence in

Bartók’s expanded tonal compositions.

Bitonality:

Kárpáti’s Bitonal Pronouncements in Allegro

barbaro, mm. 76 - 80

Kárpáti’s

(1995:373) assertion that in Allegro

barbaro examples of transitory bitonality exist for ‘in Bartók’s case we

cannot speak about … bitonality extending for the whole composition’ is

entirely accurate though the examples, analyses and conclusions he draws are

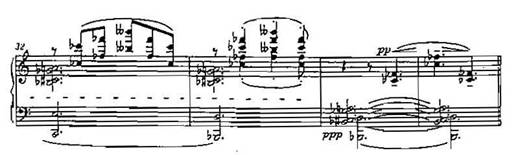

not concomitant with the philosophical basis pursued in this article. According to Kárpáti the passage in the

following example, mm. 76 - 80, represents an example of ‘semitone bitonality

[F major-F# minor] ‘… concomitant with the ambiguity of the dominant’

(1995:379). In Kárpáti’s scenario the C major chord represents either a

mistuned dominant with F# minor being the perfectly tuned tonic or F# minor is

regarded as a mistuned tonic with the C major chord being the perfectly tuned

dominant of F major (1995:373). Kárpáti does not consider the

chromatic-diatonic juxtaposition (C-F#) as being representative of a single,

all-embracing expanded “supradiatonic” context, where chromatic and diatonic

elements form a single scalar entity.

Example 4: Bartók: Allegro barbaro, mm. 76 – 80

© Copyright 1911 Boosey &

Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. Reprinted by permission

Furthermore, Kárpáti’s

“mistuned dominant” theory does not take cognizance of Bartók’s knowledge of

late-Romantic harmonic procedures resulting from the compositional influence of

Richard Strauss (1864 – 1949) which includes tritone root movement at cadential

points. The Australian-based Bartók exponent, Malcolm Gillies states in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2001/2:788,789)

that Bartók was roused as by a lightning stroke after attending the first

performance in

With regard to the

influence of Strauss upon Bartók’s harmonic language, Strauss’ employment of

tritone root movements between a chromatically lowered dominant and a diatonic

tonic to enunciate perfect cadences with juxtaposed chromatic and diatonic

functions is significant. The following example from Strauss’ opera Feuersnot (1901) serves as an example of

such a tritone root movement within a cadential context.

Example 5: Strauss: Feuersnot,

commencing 8 measures after figure 159

While

Bartók’s employment of a tritone root movement (m. 78 - 80) probably represents

the influence of late-Romantic harmonic procedures, it also depicts the

historical unfolding of the twofold properties of diatonicism and chromaticism

simultaneously inherent within “supradiatonicism.”[18] The

ensuing discussion will re-consider Kárpáti’s “semitonal bitonal” supposition

and draw conclusions with regard to bitonality as a “process and product” concomitant

with Bartók’s “supradiatonic” commentaries.

Bitonal

“Process and Product,” in Allegro barbaro,

mm. 76 - 80

This passage represents a

case of bitonality with the bass part depicting an expanded tonal

“supradiatonic” F# minor tonality through the juxtapositioning of chromatic and

diatonic root movement while the upper strand constitutes a unique modal

combination: a synthetic scale based on the Mixolydian mode starting on A with

a chromatically raised Lydian fourth degree. Thus, two horizontally represented

tonalities prevail from which the bitonal process arises with the aural result

being an intricate monotonal product in F# minor much in the way that Vinton

ed. notes that “the pitch content of [bitonality] can be analyzed (though not

necessarily heard) in terms of more than one key.”[19]

In

outlining the bitonal “process and product” hypothesis codified by Friedrich

Hartmann Bernard van der Linde (1969:7) contends that “as far as the listener

is concerned, polytonality [or bitonality] is monotonal” thereby representing

an approach akin to that of Vinton. Furthermore, Waldbauer (1996:96) states

that von der Nüll’s analytical methodology and terminology lead to bitonal

analyses, in the sense of the term that would probably be acceptable to Bartók,

“for in all cases the listener’s ear can reduce the resulting sound complex to

a single tonality.” This point of view is upheld further by Bartók himself:

‘… polytonality [bitonality] exists only for the eye when looking at the music. But our mental hearing … will select only one key as a fundamental key and will project tones of the other keys on this selected one. The parts in different keys will be interpreted as consisting of tones of the chosen key …’[20]

Waldbauer’s

observation receives poignancy when Bartók’s statement with regard to the first

of his Fourteen Bagatelles is

considered. Bartók clearly embraces the phenomenon of a monotonal product

resulting from a bitonal process:

The first [Bagatelle] bears a key signature of four sharps

(as used for C# minor) in the upper staff, and of four flats (as used for F

minor) in the lower staff. This semi-serious and semi-jesting procedure was to

demonstrate the absurdity of key signatures in certain kinds of contemporary

music … The tonality of the first Bagatelle is, of course, not a mixture of C#

minor and F minor, but simply a Phrygian colored C major.[21]

The first ten measures of this Bagatelle serve as

an example (see Example 6); the bitonal process is led visually (horizontally)

through Bartók’s simultaneous utilization of two different key-signatures for

the diatonic representation of each strand – the upper in C# natural minor and

the lower in C Phrygian. However, through an application of the fully-

Example 6: Bartók:Bagatelles

Op. 6/1, mm. 1 – 10

© Copyright Editio Musica

Budapest Music Publisher Ltd. Reprinted by permission.

chromaticized major scale, and focusing upon the

vertical, harmonic aspect, the music can be placed within a single, monotonal

perspective, whereby Bartók’s “Phrygian colored C major” can be viewed as an

analytical formulation of a bitonal monotonal product.

The “amalgamation” of C# natural

minor and C Phrygian into a tonal product represented by the

fully-chromaticized major scale of C displays the result of including chromatic

degrees as constituent scale members subordinate to the same tonic as their

diatonic counterparts. Derived from the Phrygian scale D♭,

E♭,

A♭

and B♭

are added to the diatonic major scalar system of C, with D♭,

E♭

and A♭

receiving enharmonization as C#, D# and G# respectively. The Lydian fourth, F#,

represents a further chromatic addition. Only three members of the

fully-chromaticized scale are not used by Bartók in this instance, namely the

diatonic supertonic, chromatically lowered dominant and the chromatically

raised submediant.

The existence of a strong element of notational compatibility between

the Bartók example and the fully-chromaticized major scale is of its own accord

not of primary musicological importance. However, the fully-chromaticized scale

not only provides an analytical substantiation of Bartók’s “Phrygian coloured C

major” characterization of the music, it furnishes the analyst with a valid

basis for harmonic analysis of this piece within the context of an expanded C

major as expressed by Bartók. Thus, a tonal analysis can proceed within an

unforced, natural musical environment.

Therefore, when re-considering the

five measures from Allegro barbaro, mm. 76-80, the musicological

plausibility of a monotonal product of F# minor receives endorsement when consideration

is given to Hartmann’s fully chromaticized minor scale. The product of the

bitonal harmonic enunciation of the cadential ♭V-I

in F# minor (mm. 78-80) becomes recognizable within the realm of the “supradiatonicism” of Hartmann’s

fully-chromaticized scale revealing assertions of “mistuned dominants” to be

not founded upon tonal principles of the Classic-Romantic continuum. In the

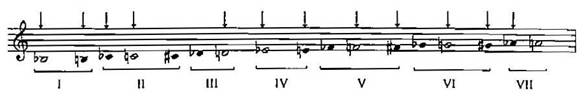

following example arrows indicate the notes utilized in the Allegro barbaro example (mm. 76-80)

where Stevens’ (1993:200) supposition regarding Bartók’s augmented scales is

realized with chromatic inflections

actually forming an integral part of the mode.

Example 7: Fully-chromaticized

minor scale of F# with arrows indicating the notes utilized in the Allegro barbaro example, mm. 76-80.

“Mistuning”

of Traditional Chord Alternation

With regard to the

mistuning of chordal structures Kárpáti[22]

elucidates the possibility of “…the notes of the perfect chord [being]

substituted by chromatic - or mistuned - variants.” The first example, to be

considered in this article, Kárpáti’s analysis of the initial four measures of

the Bagatelle No. 14 requires examination:

Here the melody, transformed into a

waltz rhythm, is accompanied by the stereotypical two-function chord

alternation of waltzes – but in place of the dominant we get an “out of tune”

chord: the most important components of the dominant are substituted: instead

of A, B♭, instead of G, F# and G#.[23]

The chord in question (mm. 2 and 4)

comprises augmented sixth properties insinuated through Bartók’s positioning of

the notes B♭ and G#. At this

juncture it is invaluable to note that Bartók’s oeuvre constitutes frequent

examples of orthography whereby, in the development of principles derived from

the “common-practice” period, the notation and tonality form a cognate

unit. In this regard Bartók’s systematic

selection of pitches reveals his concern with relating all notes in a

composition to a single tonality (Stevens, 1993:120). Therefore, his choice of

the notes B♭-F#-G# can be

considered deliberate especially in respect to tonal function within this work.

Example 8: Bartók: Bagatelles,

Op. 6/14, mm. 1 – 7

© © Copyright Editio Musica Budapest

Music Publisher Ltd. Reprinted by permission.

The construction is an

incomplete representation of a tetrad formed on the raised subdominant of D

major: G#-B♭-[D]-F#

appearing in first inversion with the note B♭

in the bass. While this chord could be construed as a German augmented sixth

with a raised fifth (F# in lieu of an F) it also constitutes a whole-tone

tetrad (half diminished seventh, G#-B-D-F# with a flattened third, B♭)

with, as we shall see, some orthographical similarity to instances in Strauss.

In this regard consider the following example from Strauss’ lied Heimkehr Op 15/5, at m.263 (B-D#-Fx-A)

and m. 333 (G-B- D#-F) where altered dominants arise,

comprising a raised fifth, in the keys of E and C majors respectively.[24]

Example 9: Strauss:

Heimkehr, Op 15/5, mm. 21 – 37

For perfect orthographical

correspondence between the Strauss examples and the Bartók chord in question,

the Bartók construction ought to have embraced the notation B♭-D–F#-A♭.

However, with reference to Bartók’s notation a plausible re-consideration of

Kárpáti’s analysis is the chord progression, D: I - #IV7 with a

whole tone tetrad on the raised subdominant with the chromatic “supradiatonic”

notes B♭

and G# being constituent members of the fully-chromaticized major scale of D.

The tritone root movement, D-G#, is in lieu of a traditional tonic-dominant

alternation with the eschewal of dominant harmony through the representation of

a strongly suggestive pre-dominant harmonic function chord. It is thus

preferable to consider the chord in question as formulated upon a raised

subdominant and not as a “mistuned dominant.”[25]

A second example of a

so-called “mistuning” of traditional tonic-dominant alternation is found during the opening measures of the first movement

of the Suite op 14 where “instead

of the traditional alternation of tonic and dominant we have alternating B♭

major and E major chords.”[26] This

point of view is explained in The Bartók

Companion (edited by Malcolm Gillies) with Kárpáti (1993:156-7) arguing for

the raised subdominant (an E major chord) as an enharmonicized lowered dominant

in a synthetic scale: B♭

C D E F# G A B♭.

According to Kárpáti this represents a scale in which

the fifth degree has now been sharpened, leaving now no

perfect fifth above the tonic B♭ … the chords accompanying the tune have no perfect fifth

intervals either, so instead of the traditional alternation of tonic and

dominant we have alternating B♭ and E major (instead of F major). E major is a mistuned or

substitute dominant …[27]

Example 10: Bartók:

Suite Op 14/1, mm. 1 – 12

© Copyright 1916 Boosey &

Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. Reprinted by permission

The triads found at m. 8 and 10

respectively, constructed above a non-diatonic root, are placed in

juxtaposition with the diatonic tonic triad, thus causing both tonal

instability and adding a sharp, biting harmonic angularity with the tritone

root separation. At m. 10 the double-degree construction clearly epitomizes the

expanded tonal idiom in the melodic decoration of the genus-defining third: E –

G(♮)G#

- B. Kárpáti probably implies that this “mistuned dominant” is an

enharmonization of the orthographically complex F♭

- A♭♭A♭

- C♭.

However, when Bartók’s orthography is considered as an accurate reflection of

the macro-tonality it becomes obvious that another clear reference to the

raised subdominant is being made, especially when “supradiatonic” notations are

considered.

Kárpáti’s synthetic scale (which is a

subset of the fully-chromaticized major scale) is based on the melodic content

of the first eleven measures and does not take cognisance of the melodic C♭

found in m. 12 nor the triads which form the harmonic accompaniment to the

melody which includes, for example, numerous references to the diatonic

dominant degree, F, as a member of the tonic triad: B♭-D-F and also the appearance of the diatonic

altered dominant ninth on F in mm. 21-26

(see below in Example 12); and the raised submediant degree, G#, as a member of

the major quality triad formed on the raised subdominant degree, E. In the

following example the notes which are utilized by Bartók during the opening

twelve measures are indicated through the use of arrows depicting their

presence within the “supradiatonic” fully-chromaticized major scale of B♭.

Each note, diatonic or chromatic, has a place within the fully-chromaticized

major scale with only five degrees not being utilized: the raised supertonic,

lowered supertonic, lowered dominant, lowered submediant and the diatonic

leading note. Thus, the seventeen member fully-chromaticized scale provides a

basis for formulating comprehensible conclusions concerning Bartók’s “supradiatonic” tones and objectifies

the rationale for disregarding the notion of a “mistuned dominant” in favor of

a chromatically raised subdominant construction. It is clear that when Bartók’s

orthography is considered to be an accurate reflection of his tonal processes

his harmonic intent is revealed without the necessity for notational

manipulation.

Example 11: Fully-chromaticized

major scale of B♭ with arrows indicating the notes utilized in the Bartók Suite Op 14/1, mm. 1-12.

Within the next seven

measures Bartók’s orthography does reveal two appearances of similar

melodic-thematic material which employ the chromatically lowered dominant as a

root. In this regard Kárpáti makes no mention of “mistuned dominants”; however,

in my ensuing analysis these chords are construed as chromatically modified

dominants (not “mistuned dominants”) which disguise the diatonic intent and

represent a widened harmonic vocabulary, thus reflecting Bartók’s

“supradiatonic” inventiveness.

The two appearances of this

phenomenon are to be located at mm. 13 – 16, F# minor (alternation of I and ♭V)

and mm. 17 – 19, D# minor (alternation of I and ♭V).

The two tonalities presented in these seven

measures represent, respectively, raised dominant and raised mediant relationships

in a descending sequence from the tonic B♭. In each instance the tonic triad is notated

diatonically with the modified dominant in the F# minor tonality being a

major/major seventh chord (C-E-G-B) and the modified dominant in the D# minor portion

being a similarly constructed minor/major seventh (A -C-E - G#).

Example 12: Bartók:

Suite Op 14/1, mm. 13 – 24

© Copyright 1916 Boosey &

Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. Reprinted by permission

“Mistuned”

Chord in Root Position

The concluding example to be

considered in this article concerns the final chord in the Suite op 14 (mm. 34 and 35 from the fourth movement). The following

example drawn from the final four measures portrays the issue under

consideration.

Example 13: Bartók:

Suite Op 14/4, mm. 32 – 35

© Copyright 1916 Boosey &

Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. Reprinted by permission

With

regard to mm. 34 and 35 Kárpáti states that

Upon the basic B♭ chord, C# is a colouring adjacent note of the major third,

A has the same function beside B♭, while G♭ substitutes the fifth, i.e. F, F♭ and C♭ are further colouring adjacent notes … In my interpretation

this is the substituting type of mistuned major triads because the major third

is substituted by a minor one [C# = D♭], the perfect fifth by an augmented one [G♭ = F#], and the octave by a diminished one [A = B♭♭].[28]

A

“supradiatonic”-oriented analysis of the tonic function harmony which concludes

the Suite reveals that the diatonic

tonic triad of B♭

major is represented by an irregularly constructed tetrad which simultaneously

comprises both “chord of addition” and “chord of omission properties.”

According to Dallin,

A simple chord to which is added one or more notes normally

foreign but used as an integral part of the sonority is designated a chord of

addition. A more complex chord from which one or more normally essential

elements is omitted is designated a chord of omission.[29]

Bartók

presents the tonic structure B♭-D–F

in a diatonically construed but “camouflaged” major seventh, B♭-D-F-A

with the tonic degree receiving unequivocal diatonic presentation with its

impact heightened through octave doubling and the C♭

representing semitonal support from above obscuring the primary harmonic

intent. The genus-defining major third apart from diatonic representation

receives semitonal support from below through the incorporation of C#; while,

the fifth degree is omitted and is replaced with coloring minor seconds, G♭,

from above and F♭

from below. Thus, the following tetrad is constructed: B♭-D–[F]–A

[+ (C♭;

C#; F♭;

G♭)]

with each of these notes being constituent members of Hartmann’s

fully-chromaticized “supradiatonic” major scale. C♭

and C# represent chord of addition properties while F♭

and G♭

highlight chord of omission properties. This is indicated in the following

example.

Example 14: Fully-chromaticized major scale of B♭ with arrows indicating the notes utilized in the Bartók Suite Op 14/4, mm. 34 and 35.

Considered within this scenario this

tetrad with chord of “omission” and “addition” properties does not constitute

the substitution of mistuned major triads but

a tonic-inspired representation synthesising diatonic and chromatic properties

which both simultaneously propagate and evade the diatonic enunciation of the

tonic triad.

Furthermore, the quartal construction

(C♭-F♭)

which coloristically accompanies the tonic tetrad (mm. 34 and 35) is directly

related to the linear quartal melodic profile in mm. 32 and 33 with the

vertical intervallic presentation during the final two measures acting as a

final reminder of the tritone dichotomy which, from the opening measures of the

first movement discussed above, permeates this movement and the Suite as a whole. Enharmonicized, they

represent the dominant (B) and tonic (E) of E major though their presence does

impinge upon the strength of the B♭

major key at the close; in this regard it is interesting to note that both B

and E are constituent members of Hartmann’s fully-chromaticized major scale of

B♭.

Conclusion

In conclusion it should be noted that

while Bartók would prefer the label of “polymodal chromaticism” in his later

reflections,[30]

his earlier “supradiatonic” pronouncements reveal that his compositions,

notwithstanding surface details, have a clearly tonal foundation based upon

“common-practice” principles. In the case of the Fourteen Bagatelles, Allegro

barbaro and the Suite Op 14, this is clearly identifiable and

negates assertions of “mistuned dominants” and other analytical approaches

which are not founded upon Classic-Romantic tonal postulations. The analyses

presented in this article reveal Bartók’s well-ordered tonal organization

representing a developmental growth grounded in the dissonant textures of the

early twentieth-century.

Orthographically Bartók develops a

concept of tonality which is complemented through Hartmann’s formulation of the

fully-chromaticized scales. Hartmann’s fully-chromaticized scales allow

firstly, for the development of a harmonic perspective within an inclusive

tonality which contains both diatonic and chromatic tones and secondly, through

their construction, harmonic orientations and enharmonization procedures become

observable. Furthermore, they are a vehicle whereby Bartók’s intuitions

regarding “supradiatonicism” and “bitonalism” can be understood and

harmonically contextualized. The musical and theoretical integrity inherent

within their construction makes them a relevant basis from which a perspective

on the true nature of Bartók’s harmonic imagination can be gleaned.

Each of the aforementioned aspects

act interdependently upon each other within Bartók’s remarkable aptitude for

assimilating ideas and then reproducing them within the expanded tonal idiom.

In conclusion, Graf’s comments on this are perhaps the most pertinent.

He [Bartók] possesses not only the fantasy of genius, but

the lucidity of a genius as well. The music … that Bartók created, his

harmonies and his rhythm, were studied with intelligent keenness. His artistic

world is not just a sphere of fantasy, but a world of logic. Bartók’s artistic

development … is without any arbitrariness, clear and sure … Imagination,

intelligence and morality are united in Bartók’s work, as they are in every

great art.[31]

Bibliography

Antokoletz, E. 1993. The Bartók Companion. Edited by M.

Gillies.

Bartók, B. no date. Allegro barbaro (1911), Universal

Edition Nr 5904.

_______ 1971. Fourteen Bagatelles for Piano, Op 6.

_______ no date. Suite, Op 14.

_______ Bartók

Essays, ed. Benjamin Suchoff,

Bukofzer, M. 1947. Music in the Baroque Era.

Dallin, L. 1974. Techniques

of Twentieth Century Composition: A Guide to the

Materials of Modern Music. 3rd. ed.

E.W. 1932. ‘Reviewed Work: Moderne Harmonik by Edwin von der Nüll’. Music and Letters 13/2, 235-236.

Gillies, M. 2001. New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians Vol 2 Edited by

Graf, M. 1978. Modern Music, translated by B. Maier.

Hartmann, F. H. 1934. Harmonielehre.

Hartmann, F. H. 1956. Musical

education in the University.

Kárpáti, J. 1993. The

Bartók Companion. Edited by M. Gillies.

_________

1994. Bartók’s Chamber Music

_________ 1995. ‘Perfect and Mistuned Structures in Bartók’s

Music’. Proceedings of the International Bartók Colloquium,

Mason,C. 1953. ‘Reviewed Work: The Life and Music of Béla Bartók by Halsey Stevens.’ The Musical Times 94/1330, 564.

Paxinos, S. 1975. ‘Hubert du Plessis’

Elegie Op.1 No. 3.’ Musicus 3/2,

40-43.

Simms, B. R. 1986.

Music of the Twentieth Century.

Stevens, H. 1993. The Life and Music of Béla Bartók, 3rd. ed. Edited by M. Gillies.

Strauss, R. 1964. Lieder-gesamtausgabe, Vol. 1.

Van der Linde, B. S. 1969. Polytonality: Another case of Atonality?

Van der Linde, B.

S. 1993. Study Guide for HARMPO-W, 2nd.

rev. ed.

Vinton, J. ed. 1974. Dictionary of Contemporary Music.

Vinton,

J. 1966. ‘Bartók on His Own Music’. Journal

of the American Musicological Society 19/1, 232-243.

Waldbauer,

Yates, P. 1967. Twentieth Century Music.