LOOPS:

An Informal Timbre Experiment

Robert

Erickson

Musical

structures, no matter what their particular musical dimensions, rest upon

perceptions of similarity and difference.

We know something of pitch structure, less about rhythmic structure and

almost nothing about timbre as a structural element in music. Indeed, it has commonly been thought to be a

subsidiary and/or ornamental musical characteristic, without potential for generating

structure. Nevertheless, there are

compositions by Webern, Varèse

and a few other composers which indicate that the prevailing view may be

wrong. LOOPS is

an experiment to obtain information about the question: can there be

specifically timbral organization in music.

The

notion of a structured sequence of sounds whose organization is not primarily a

matter of pitch was first proposed by Schoenberg (1911) in the final paragraphs

of his Harmonielehre.

I

cannot readily admit that there is such a difference, as is usually expressed,

between timbre and pitch. It is my opinion that the sound becomes noticeable

through its timbre and one of its dimensions is pitch. In other words: the larger realm is the timbre,

whereas the pitch is one of the smaller provinces. The pitch is nothing but timbre measured in

one direction. If it is possible to make

compositional structures from timbres which differ according to height, [pitch]

structures which we call melodies, sequences producing an effect similar to

thought, then it must also be possible to create such sequences from the

timbres of the other dimension from what we normally and simply call

timbre. Such sequences would work with

an inherent logic, equivalent to the kind of logic which is effective

in the melodies based on pitch. All this

seems a fantasy of the future, which it probably is. Yet I am firmly convinced that it can be

realized.1

But

Schoenberg composed no klangfarbenmelodie himself, and in a letter of

1951 to Rufer (1969) he discussed the idea again,

this time with a slightly different emphasis.

After remarking that "Webern's

compositions realized only the smallest part of my conception of

"klangfarbenmelodie" he goes on to say that what might appear to be

klangfarbenmelodie in his own works is always some kind of polyphony, and that

these isolated instances are not really melodies. Melodies require a constructive unity, an

organization, and "in my conception such (klangfarbenmelodie) forms had

become something new for which as yet there is no description, because, indeed,

they do not yet exist."

The

remark about polyphony is especially interesting, because it is clear that

klangfarbenmelodie must be compound, i.e., exhibit more or less easily

perceptible polyphonic characteristics, since the constituent timbres tend to

cohere on the basis of timbre class. The reason it is difficult to find

unequivocal examples of klangfarbenmelodie (in Schoenberg's 1911 sense of the term) may

therefore be related to the tendency of linear sequences to break into the

separate perceptual streams or channels which are implicit in extended melodies

as "hidden polyphony" or compound melodic line.

The

formation of perceptual streams or channels was first investigated by Miller

and Heise (1950).

They found that a rapid trill broke into two separate streams when the

frequency distance exceeded about one seventh of an octave in music

ranges. They named the region of

transition the "trill threshold". Norman (1966, 1967) commented upon the experiment of Miller and Heise, offering several possible explanations of the

phenomenon, and reported that when listeners were asked to decided whether a

probe tone followed the higher or lower of two repeating background tones, they

had little difficulty when the frequency of the probe tone was between those of

the two background tones, but when the probe tone was much higher or lower than

the background tones, the task was correspondingly more difficulty. Warren and his associates (1969) found that in

listening to a tape loop of four sounds (40 Hz. square wave, 1000Hz sine wave,

the vowel "ee", white noise burst) played

at a rate of 200 msec for each of the four items,

their subjects had great difficulty in judging the order of the sounds. The four different sounds tended to form four

separate perceptual channels unless played very slowly. Bregman and

Campbell (1971)

suggested that stream formation is a primary auditory phenomenon, and Bregman and his associates have performed a number of later

experiments related to the perception of melodic patterns in musical

situations.

My

LOOPS experiment is an attempt to discover whether concepts of perceptual

stream or channel can be helpful in a musical understanding of the effects of

fast discrete changes of instrumental timbre.

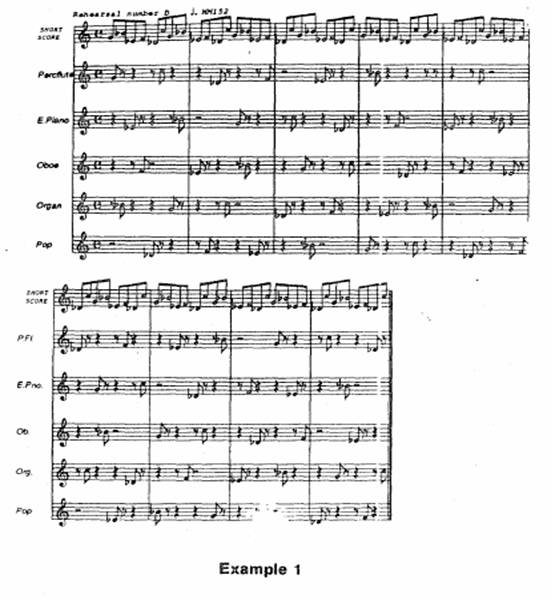

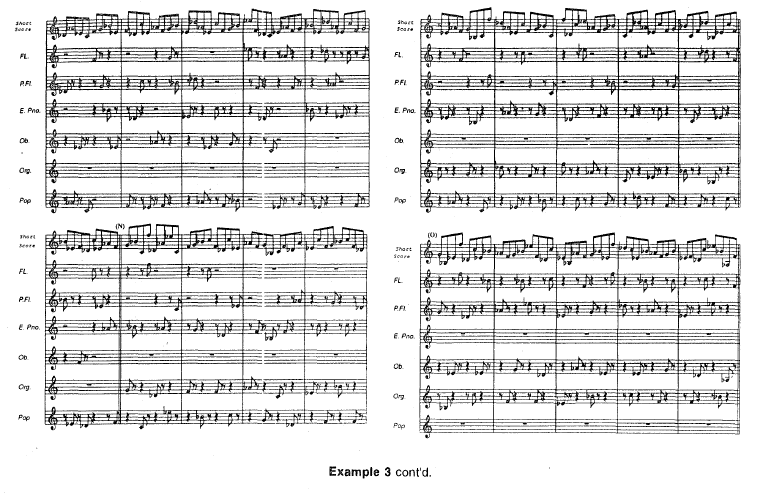

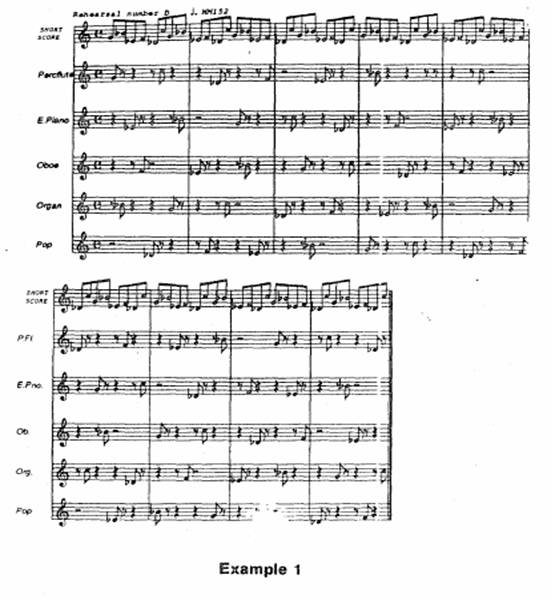

If a repeating melodic pattern of six pitches is performed by five

instruments, with each instrument playing a single note, in the manner of a hocket, then each pitch of the pattern will eventually be

played by a different instrument (Example 1) and one can form opinions about

the effects of the timbral versus the pitch

dimension.

Clearly

one is able to listen to this delicious confusion in more than one way: (1) one

may follow the tune through its changes of timbre; (2) one may begin to form

perceptual streams on a pitch basis (in this kind of listening the C/B flat

patterns of the high line and the E flat/D flat patterns of the low line are

clearest); (3) one may follow the line of a single instrument (marimba is easy,

clarinet is more difficult); (4) one may listen - and this is most likely - in a mixed manner, using (1) or (2) or (3),

depending upon the detailed musical situation

at any particular moment.

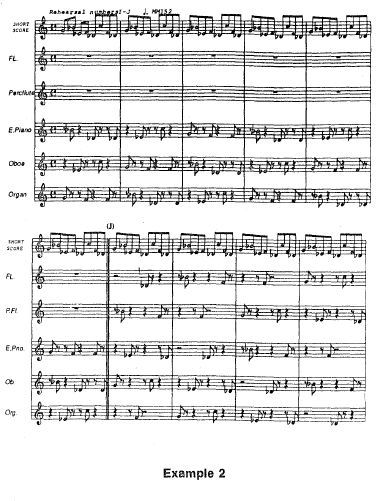

With

fewer instruments one might expect the channeling to be stronger, because each

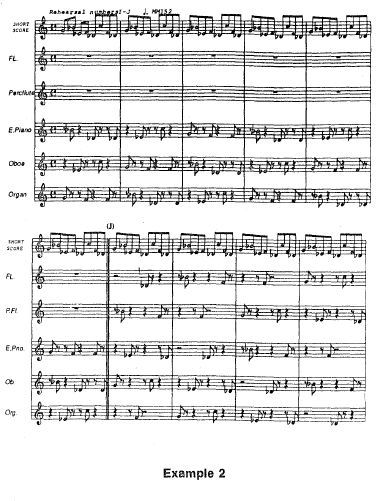

instrument is heard with fewer rests between appearances. Example 2 employs three instruments at I and five instruments at J in an eight pitch melodic

pattern.

It

may be very slightly easier to follow an individual instrument line when three

instruments are employed, but not much.

Following an instrument appears to depend more upon the special

characteristics of the instrument, especially its attack quality, in relation

to the total group or subgroup. The

marimba line can be tracked almost too easily, but the other two instruments at

I are not so easy to disentangle.

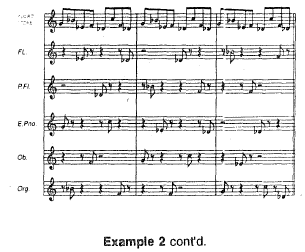

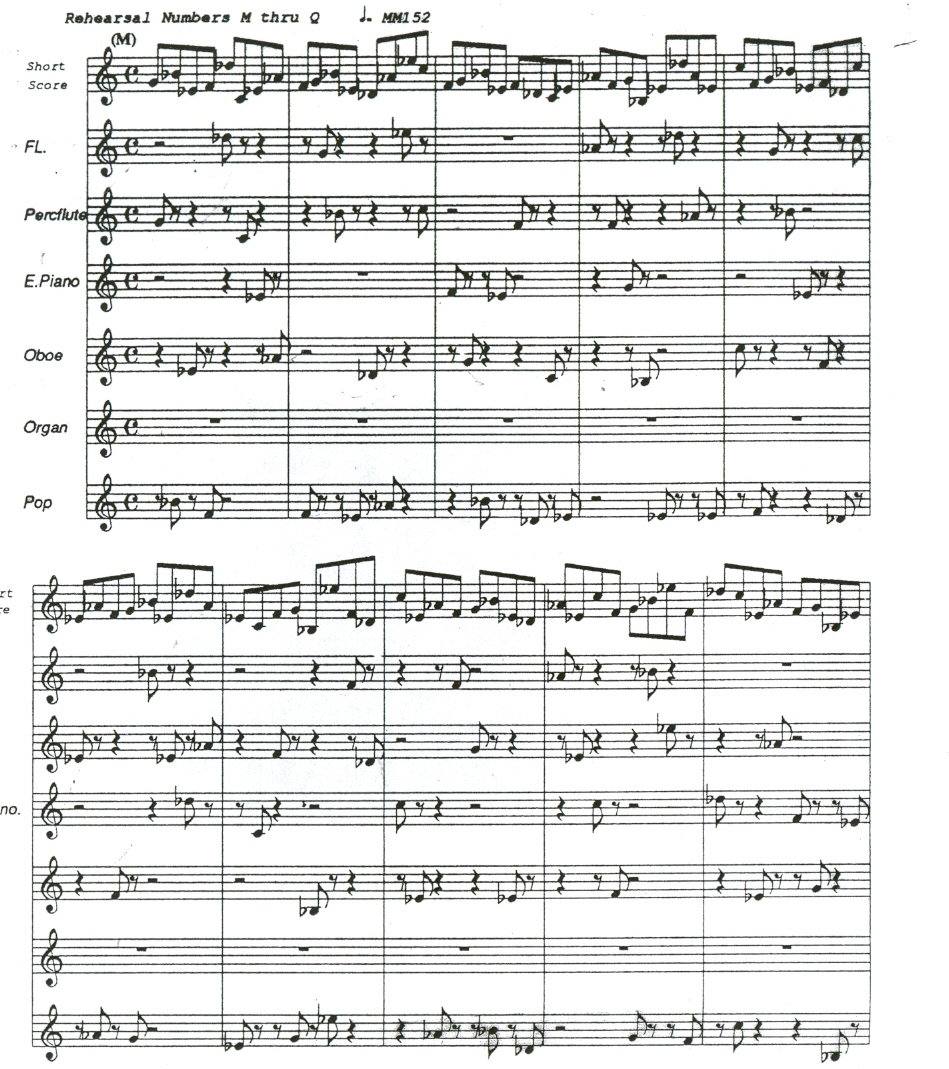

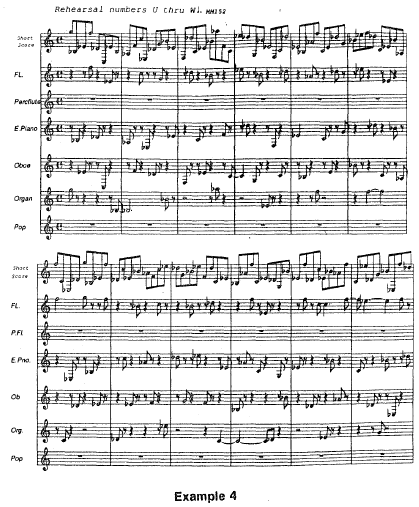

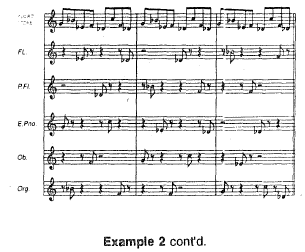

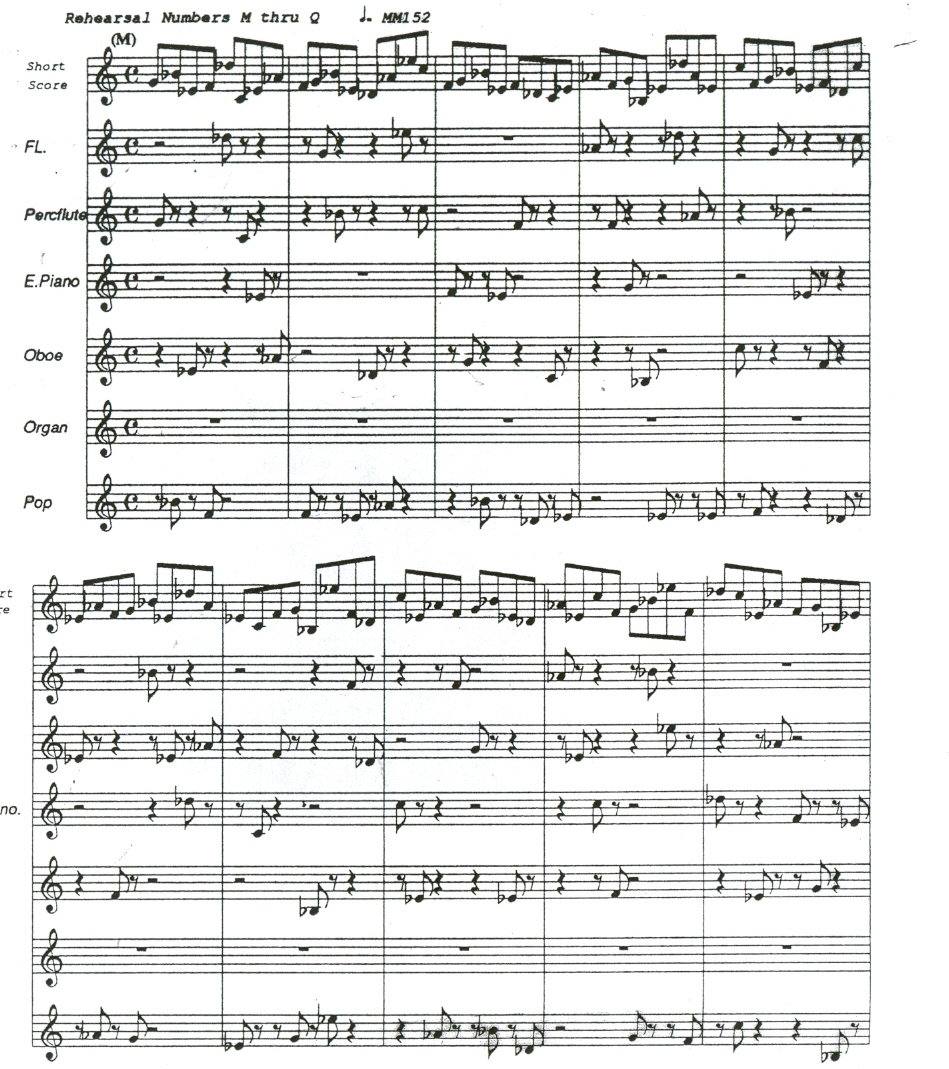

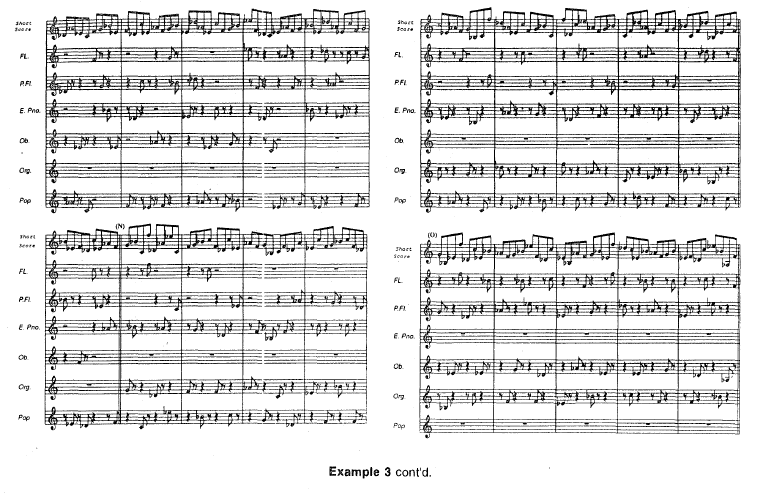

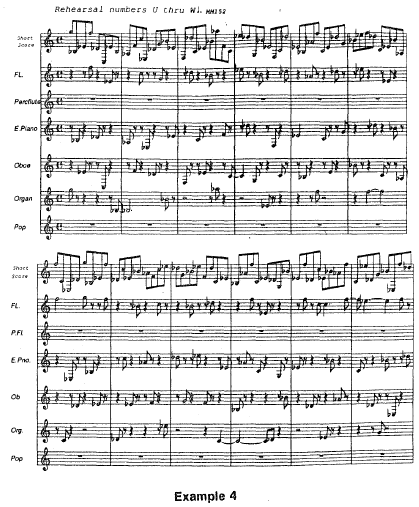

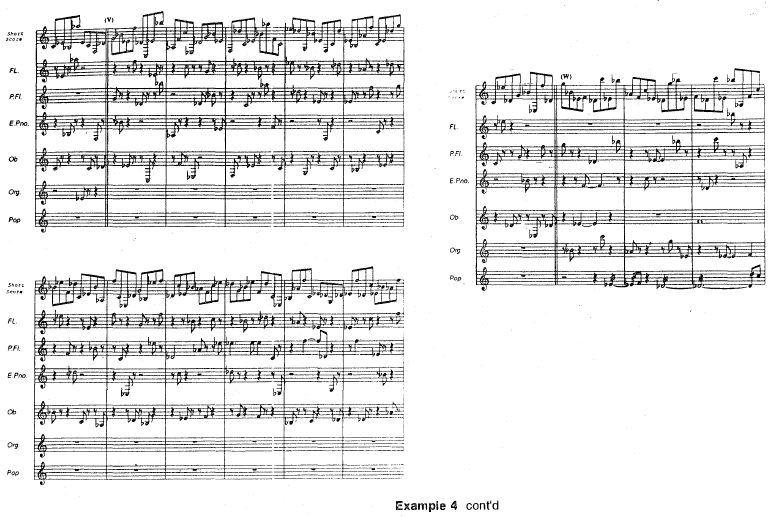

If

a melodic pattern has a wider pitch ambit, Example 3, one could expect more

channeling on a pitch basis. Example 3

also uses a more complex pattern: a nine

tone sequence plus a nine tone variant (simple repeating sequences soon become

boring) with enough octave displacements to make a three octave range. A further complication here is that instead

of simply rotating the instruments in sequence they are used in patterns. Sometimes the pattern is modified because a

pitch is not available on a particular instrument. Especially interesting is a

noticeable change of grouping which must be timbre determined -at O, after the

complex pattern of N and before the complex pattern of P.

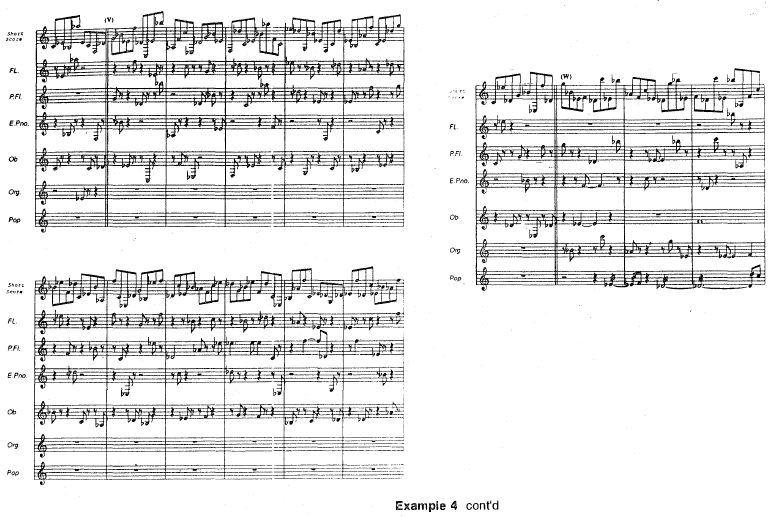

If

one lengthens notes in one of the instruments a melodic channel in the timbre of

the instrument will be formed. There is

nothing musically new or problematical in passages such as are shown in

Example 4, although perceptual channeling becomes very complex, and one is very

aware of texture and of the intensified disjunction (contrast) between the

instrumental timbres. Notice too, that

the pitch range has been further extended.

It

appears that the answer to the question, can a melodic figure be preserved while

undergoing radical changes of instrumental timbre is yes - but. The "but" includes matters such as

the total range of the melodic pattern, the tempo, the particular instruments

involved, their timbres at the specified pitches and the type of articulation

of the attack and decay. It is easy, but

allowing only slight overlaps of sound, to turn a precariously sequential

melodic formation into something clearly polyphonic.

How

strong is the effect of the timbre pattern vis a vis the melodic

pattern? Strong, but no general

statement is possible. The sub-patterns

produced by the competition between pitch channeling and timbre channeling are

local effects, but controllable, and full of compositional potential, not least

in the area of rhythm. It is of great

interest that, in spite of the meter of the counting process, the patterning is

chiefly a result of tonic accent, loudness of the various notes in an

instrument's repertory, articulation of attack and decay, etc. Timbral

distinctiveness or vividness in any micro context sounds very important,

perhaps crucial, to the formation of the sub-groupings, and, therefore, the

rhythm and the higher levels of the musical organization.

Why

is the number of effective perceptual categories often less than six, even when

all instruments are playing? The answer

to this is an interesting problem in psychoacoustics (are psychologists

listening?) but it is of musical interest too, for the confusions among

clarinet, saxophone and bassoon in certain contexts of LOOPS mean that there

are different perceptual contrast relationships in different musical

situations. The distinctiveness of a

timbre, and therefore its contrast potential, is different in different

registers (or even different pitches) in a non-simple way. we cannot think

merely in terms of gross contrast - clarinet, trumpet, saxophone, etc., but

most always consider the timbre of the instrument at whatever particular pitch

it is playing. Now, if certain

instruments can be composed in such a way that either they can be made to tend

toward homogeneity or confusability of sound or toward diversity and

distinctiveness of sound, then there is a possibility for a structural

interplay between timbre and pitch, and that is the most important musical

insight to be gained from LOOPS.

----------------------

I wish

to thank the LOOPS players, who rehearsed a difficult musical score for many

hours over a period of months. They

included Mel Warner, clarinet, Edwin Harkins, trumpet, Jean-Charles Francois,

marimba and Ron Grun, bassoon, from the Project for

Music Experiment, UCSD, and Larry Livingston alto saxophone and Peter

Middleton, flute, from the Department of Music, UCSD. Charles White, from the Project for Music

Experiment, was the recordist.

Encinitas,

March

26, 1973.

Bibliography

Bregman,

A.S. and Campbell, J. (1971): "Primary Auditory Stream Segregation and

Perception of Order in Rapid Sequences of Tones," Journal of

Experimental Psychology Vol. 89, no.2, 244-249.

Miller,

B.A. and Heise, G.A. (1950): "The Trill

Threshold," Journal of the Acoustical Society of America Vol.

22, 637-638.

Norman,

D.A. (1966): "Rhythmic Fission: Observations On

Attention, Temporal Judgements and the Critical

Band," unpublished ms. Harvard University,

1966.

Norman,

D.A. (1967): "Temporal Confusions and Limited Capactiy

Processors, Acta Psychologica,

Vol.27, 293-297.

Rufer,

J. (1969): "Noch

Einmal Schoenbergs

Op.16," Melos,

367.

Schoenberg,

A. (1911): Harmonielehre,

U.E. No.3370 Leipzig/Wien, p.471.

Warren, R.M.; Obusek, C.; Farmer, R.; Warren, R.P. (1969): "Auditory

Sequence: Confusion of Patterns other than Speech or Music," Science

Vol. 164, 2 May,

536-537, .

1 Schoenberg, Harmonielehre Leipzig and Vienna, 191, pp

470-471.